Copper Chopper

Cobra keeps it real with a Seventies stretch-job

BRIAN CATTERSON

"IT'S SO MUCH easier now,” laments renowned custom-bike builder Denny Berg. “Back in the ’70s, we had to make everything ourselves. These days, people say they ‘build’ bikes, but they’re really just assembling them from aftermarket parts.”

Berg, for his part, still builds bikes the old-fashioned way. He has to, because Cobra Engineering pays him to produce one-of-a-kind customs, the kind that grace magazine covers and stop show-goers in their tracks.

Regular readers have seen Berg’s handiwork before, most recently on the Hot Rod Honda VTX1800 featured in CW's May, 2001, issue. But whereas that bike and various other contemporary-cruiser projects were meant to promote sales-both of Cobra’s wares and the bikes themselves-the “Copper Chopper” came about purely because Cobra proprietors Ken Boyko and Tim McCool thought it was, well, groovy.

The way Berg sees it, it’s a logical evolution. “Everything comes back around,” he says. But rather than just re-create one of the CB750s or Z-ls that he built as a youth, Berg wanted to “take the concept into the next millennium.” For three years, he and Boyko looked at modem engines, and found that they were all “either water-cooled or ugly.” Then, last year at Daytona, they found what they were looking for.

Berg picks up the story: “We were walking around the Honda booth when Ken pointed to a Nighthawk 750 and said, ‘What is that?' It’s perfect!’”

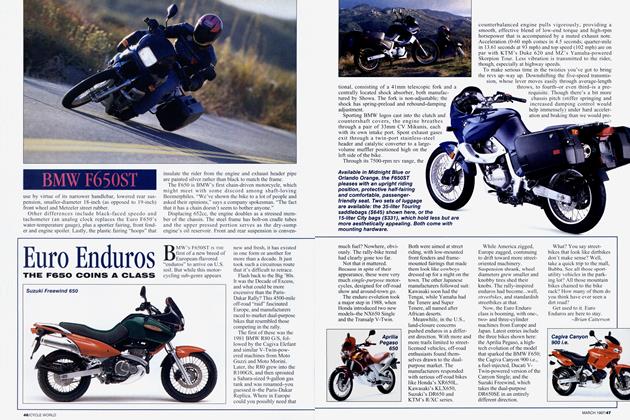

First order of business was bead-blasting the black paint off the engine, rounding off the comers of the cylinder fins to resemble an old single-cam Honda and then polishing the aluminum to a glistening sheen. A set of Mikuni flat-slide carburetors with open bellmouths took up residence on the intake side, while a set of 4-into-4 straight pipes handmade by McCool handled the exhaust.

With the engine complete, attention turned to the frame. Boyko paid $1500 for a rigid Harley-Davidson aftermarket job, but by the time Berg got done bending, cutting and welding it to accept the Honda engine, the only unadulterated parts remaining were the steering stem and the axle carriers!

A chopper wouldn't be a chopper without an extended fork, so leading the way is a standard Sportster Showa fork kicked out at 38 degrees and equipped with 6-inchover stanchions from Forking By Frank. Berg turned the fork legs on a lathe to remove unnecessary bosses, but spared the left fender mount so that he could attach a tiny two-piston Performance Machine brake caliper, which grasps a diminutive 8.5inch disc.

“A big brake would just overpower that skinny tire,” Berg says in reference to the ribbed Cheng Shin, one of the few street tires still made to fit a narrow 2.15 x 18-inch wheel.

Contrasting the skinny front tire is a fat rear, a 180mm Metzeler on a 6.0 x 18-inch rim, the widest that would fit. Again, PM provided the brake, this time a four-piston caliper grasping an 11.5-inch rotor. Covering the rear meat is an aftermarket steel fender that Berg split down the middle, tapered, then re-welded and welded to the frame. The spaghetti-thin aluminum fender struts are purely decorative, while the license-plate frame cleverly slides into the wheel hollow for show, and out for go.

The elegant Contour hand and foot controls also came from PM, the former held by a low, drag-style tubular handlebar and the latter located high and forward in the tradition of the ’70s Frisco-style choppers.

“We used to ride around with our elbows resting on our knees,” recalls Berg. “Now, we all have bad backs.”

The low, low seat and stretched-out fiberglass fuel tank were made from a set of drawings by Cobra stylist Mike Rinaldi. Last came the copper paint that gave the bike its nickname. “I went to the International Auto Show and saw this color on a Buick concept car, and knew right away this was it,” recalls Boyko. “We originally talked about painting it silver metalflake, but that was just too ’70s. We wanted this bike to be what you would end up with if you were building a four-cylinder chopper today.”

Berg reinforces that conviction. “In building this bike, I purposely didn’t look at any of my old chopper magazines,” he says. “I wanted it to recall a ’70s bike, not to he a ’70s bike.”

Coffin tanks and Maltese Cross sissybars be damned, there’s a new kind of chopper in town.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontLetter of the Month

April 2002 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Mouse That Roared

April 2002 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCThe Rpm Chronicles

April 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

April 2002 -

Roundup

RoundupNew Bmw Über-Tourer Twin

April 2002 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupUltimate Towing Machine?

April 2002 By David Edwards