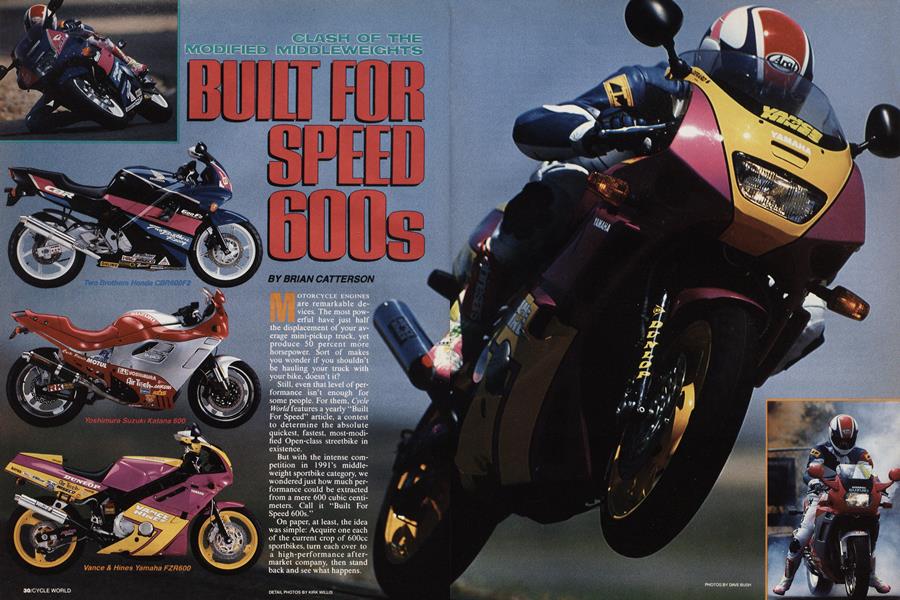

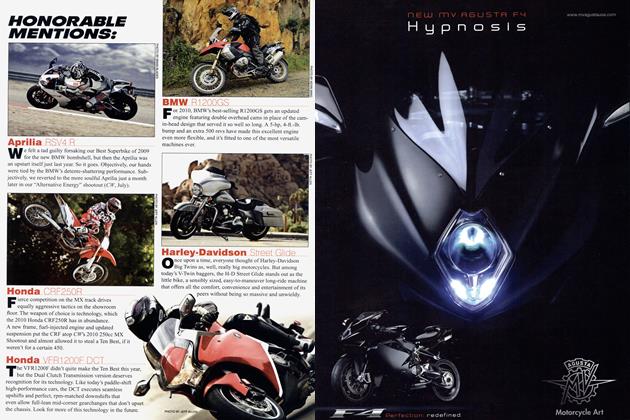

BUILT FOR SPEED 600s

CLASH OF THE MODIFIED MIDDLEWEIGHTS

BRIAN CATTERSON

MOTORCYCLE ENGINES are remarkable devices. The most powerful have just half the displacement of your average mini-pickup truck, yet produce 50 percent more horsepower. Sort of makes you wonder if you shouldn’t be hauling your truck with your bike, doesn’t it?

Still, even that level of performance isn’t enough for some people. For them, Cycle World features a yearly “Built For Speed” article, a contest to determine the absolute quickest, fastest, most-modified Open-class streetbike in existence.

But with the intense competition in 1991 ’s middleweight sportbike category, we wondered just how much performance could be extracted from a mere 600 cubic centimeters. Call it “Built For Speed 600s.”

On paper, at least, the idea was simple: Acquire one each of the current crop of 600cc sportbikes, turn each over to a high-performance aftermarket company, then stand back and see what happens.

Choosing those companies was as easy as reading the Daytona roadrace results. We simply approached those teams that represent the Japanese manufacturers in U.S. roadracing: Two Brothers Racing for Honda, Muzzy R&D for Kawasaki. Yoshimura for Suzuki, and Vance & Hines for Yamaha.

So, one warm, spring day, we loaded our quartet of' test hikes into the CW box van and ventured out onto the Southern California freeway svstem, stopping to deliver the bikes to the aftermarket firms where (we hoped) their performance potential would be fully realized.

I he only rule for our contest governed displacement: Cylinder bore could be increased I mm, but the stock stroke had to be retained, in keeping with current roadrace rules. I he bikes also had to remain street-legal, though we would permit the use of aftermarket exhaust systems, w hich in many states constitutes an equipment violation.

Previous big-bore Built For Speed shootouts did not allow for gearing changes, but they also did not include roadrace track testing. Given that all of these 600s have, at one time, had their chassis developed for supersport racing, it seemed a shame not to reap the benefits of that development. So, we added timed laps at a roadrace track to the usual dragstrip and top-speed categories, and allowed the competitors to change sprockets to maximize performance in each arena. We also did not expressly ban the use of race gas. as we have in the past, opting to trade inconvenience at the pumps for maximum performance.

Twisting the throttles during our performance testing would be Associate Editor Don Canet, an experienced roadracer who is responsible for the numbers posted in all of ClUs road-test data panels. Following performance testing, we would take the bikes on a street ride to evaluate their roadworthiness. And finallv. provided the bikes survived. we would subject them to dv no testing to determine just how much horsepower we were talking about (see accompanying graphs).

A measure of' the seriousness given these BFS 600s was show n when we returned to Vance & Hines to pick up the FZR. There, occupying pride of place in the company’s plush conference room, was a bike bristling with technology, painted to resemble the teams' racebikes. The tech rundown on the bike was more like a military briefing, as owner Terry Vance, race-team mechanic Ron Foster and technician Steve Derksen explained in detail the inner workings of this nitrous-oxide-injected projectile, proudly displaying samples of' the centrifugal clutch-lockup device and adjustable ignition module they had fitted.

“Never." they told us, “ever." they warned, “give it full throttle with the NOS system armed at low rpm, or while in first or second gear. If you do, it'll either throw a rod, or flip over and pound you into the ground like a stake.”

This was a serious effort.

Dragstrip

The scene at Carlsbad Raceway reinforced that impression. Two Brothers Racing took a low-key approach at the dragstrip. represented by tuner Mike Velasco and assistant Bob Miranda. Yoshimura had a lone rep, mechanic Scott Link. The Vance & Hines contingent, however, included the aforementioned threesome, plus Vance's partner, legendary engine guy Byron Hines.

Muzzy R&D, meanwhile, was a disappointing no-show. With the U.S. round of the World Superbike Championship fast approaching. Muzzy's attention was focused on Scott Russell’s Superbike, and our bike was still “in a million pieces." Scratch one ZX-6.

First to roll to the line at Carlsbad was the Honda, and it immediately became clear that Velasco had done his homework. The bike looked virtually stock, was the most lightly modified of the three, and was ready to run right out of the van. On just the third pass of the day. Canet got the combination perfect, dumping the Honda's clutch, howling the rear tire, barely lifting the front, blitzing the quarter-mile in 10.85 seconds at 126.76 mph-substantially better than the stock CBR’s 1 1.23/122.1 1. Velasco later experimented with a fuel additive that appeared to boost low-end power, and then altered the gearing so that Canet could make one less shift, but neither effort improved on the earlier mark. Indeed, that time stood as the quickest overall until nearly dusk, hours later.

Next, the Yoshimura bike took to the track. At first, the proximity of the Katana's kickstand tang to its left-side rearset footpeg interfered with smooth shifts, so Fink cable-tied the stand out of the way. The next few runs were then thwarted by ignition trouble, which was traced to the kickstand safety switch cutting out the ignition. Thai fixed, it was determined that the bike was geared way too tall, because even with lots of clutch slippage to get the revs up, the engine would bog once the clutch was f'ullv engaged. Changing to a three-tooth-larger rear sprocket gave the bike the acceleration it needed to record its best run, 1 1.33 seconds at 1 2 1.29 mph —not in the 10s. but still a full half-second quicker than the Stocker’s 1 1.83/1 13.78.

Vance & Hines was next up. but the FZR's carburetion was less than perfect, the bike bogging an\ time Canet backed off the throttle, then cracked it open. Fven with the nitrous-oxide system disarmed. Canet struggled, the engine's sudden power delivery and clutch-lockup device conspiring to make for difficult leav es, the bike alternately wheelving and bogging. Pulling the fork tubes up in the triple clamps tamed the wheelies. but the best ( 'anet could manage without nitrous was an 1 1.24 at 124.48. barelv better than the Katana, and not in the same league as the CBR600.

“Screw this. Turn on that blue bottle.'' said Hines, and Foster armed the NOS system. But after just one run on the “squeeze" (what the cool guvs call nitrous oxide), the clutch began to slip at high rpm. Foster replaced the clutch plates and added more weight to the clutch lockup, after which Hines climbed aboard fora shakedown run. When the bike wheelied violently, Hines excitedly yanked in the clutch lever, and the high pressure created by the fastspinning centrifugal clutch-lockup dev ice spun the clutch pushrod, damaging the clutch actuator.

Hines and Foster managed to repair the clutch pushrod, but from that point on. we were warned not to disengage the clutch at high rpm. ( lutehless shifts became the norm.

Another run was aborted when the Yamaha's masterlink broke, the chain flying off the sprockets, and yet another pass went for naught when the NOS bottle ran empty part way down the track. I urns out the bottle—located under the tailsection—was good for only two or three runs.

While the NOS was being recharged. Oanet got some coaching from Vance, holder of 1 3 Nil R A world titles, on how to launch the tricky FZR. Canet's first effort af ter the advice was only an 1 1.33, but terminal speed was up to 136.57 mph. Clearly, this bike had potential. And no one present will ever forget the sound as the NOS system kicked in at full throttle in second gear, the front wheel shooting skyward and the revs picking up instantaneously. Subsequent runs saw experiments with jetting, nitrousoxide/fuel-enrichment ratios, shift points and ignition advance. all w ith some measure of improvement. The absolute best run of the day was recorded on the penultimate pass, when Canet tore off a 10.71/139.31. Just how impressive is that? Well, it's nearly a second quicker and more than 22 mph faster than the Stocker’s I 1.65/1 17.18. and tantalizinglv close to the 10.48 showing put on by last month's test Kawasaki ZX-1 1, with a terminal speed 5 mph faster than the big Ninja's. Incredible stuff.

With a terminal speed more than 1 2 mph faster than the Honda, there was no arguing that the Yamaha was the fastest thing at the dragstrip. But the Yamaha was just . 14 of a second quicker than the Honda, and had taken an additional 16 runs to get dialed-in. The Katana was never in the running, but the improvement over stock was noteworthy. A pattern was dev eloping.

Top Speed

We met again the very next morning at Cycle Worlds top-secret testing facility, a closed road deep in the desert, where w e would see just how fast each of these hikes was capable of going.

Again, the Honda was up first and. running on the fuel additive, it managed 149 mph. Velasco was disappointed: The team's supersport bikes had gone 156 mph at Daytona. He fell better later when the radar gun recorded a 157-mph pass—1 3 mph faster than the stock CBR—with the bike running on straight race gas.

Next up was the Yamaha. Running without nitrous, it went “just" 1 52 mph.

"All 1 could think about was the chain falling off. ’ Canet joked af ter his first run on the Yamaha, a reference to the previous dav's occurrence. He didn't know it at the time, but there was some truth in what he said. Somehow, both of the Yamaha's chain adjusters had fallen off during the pass, as had one of the air-intake hoses. I he chain adjusters were hastilv repaired with parts from under the hood of 1 )erksen's Iovota pickup, and the intake hose was quickly refitted. Then, with the NOS system armed, the bike began to sputter whenev er it was on the squeeze. 1 his was traced to a loose nitrous-oxide line, also easily fixed. Another lost masterlink clip later, the bike blew past our radar gun at a scorching 165 mph, 26 mph faster than the stocker, and faster than anv stock Open-class streetbike we've ever tested, save for the 176-mph ZX-1 I. ( an you say impressive?

After some sprocket juggling, the Yoshimura Katana ripped off several ev ent-free passes, the f astest being 144 mph. ( 'learly not on par w ith the I londa and Yamaha, but still 1 2 mph faster than stock.

The Yamaha had won again, no contest, though it could be argued that the Honda was still the leader in the “normally aspirated" division.

Roadrace

Willow Springs International Racewav was the site for the final round of our numbers gathering. lop racers on modified 600s with slicks circulate the high-speed. 2.5mile. nine-turn road course in just under I minute, 30 seconds, so it would be interesting to see what these built 600s would turn there. There would be no lap records today, however, as Vance & Hines decided to unplug the NOS system at the roadraee track. The bottle would have been depleted after two or three laps anyway, so the V&H team bet that the F ZR's handling prowess alone would be enough to hold them in good stead.

They were right. Though the FZR's carburetion was still a problem. Canet turned the quickest lap of the day at 1:3 1.38. largely due to the Yamaha’s unflappable chassis, improved over stock by an aftermarket rear shock and radial tires. One component meant to upgrade the bike's handling, though, didn't: The steering clamper was way too stiff, causing the bike to wallow, so we removed it. Still, the bike never shook its head, even over Willow's fast, crested Turn Six. Canet also didn’t care for the megatrick, ISR six-piston front brakes, which offered excellent stopping power, but which felt vague at the limits of adhesion. Foster said that this was because the master cylinder was too small for the application.

Once again, the Honda was a close second, despite a not-insignificant headshake in Turn Six, and a busyness in ultra-fast Turn Eight that was anything but confidenceinspiring. Nonetheless, Canet cranked off a best lap time of 1:31.73.

Unfortunately, the Katana never got a fair shake at Willow Springs. First, a pinched petcock vacuum line caused it to sputter to a halt, then, after just a few exploratory laps—the best of which was a high 1:34—the bike was parked with a seized rear-wheel bearing. This may, in fact, have hurt the bike’s effort during the previous day’s topspeed testing. A replacement part was promptly dispatched from Yoshimura’s warehouse, but by the time it got to Willow, the notorious high-desert winds had begun to blow, making any additional attempts futile. Still, the Katana earned high marks at the track for its composed ride, and Canet felt it should have been able to turn times in the 1:32-33 range.

Street

The final portion of our testing was, in some ways, the most important. Sure, the Yamaha had proven itself the fastest thing between two points, whether those were separated by a straight or curvy line, but could we live with it on the street? The answer, at least initially, was a resounding no. Without a choke lever, the Yamaha was hard-starting—that is, unless you used the NOS system’s fuel-enrichment circuit by momentarily triggering the system while leaving the nitrous-oxide bottle turned off. Carburetion was still poor, running cleanly only over 8000 rpm, and accepting only partial throttle at anything lower. This was especially annoying while passing a slower vehicle, particularly on a two-lane road, where the bike had a nasty habit of hesitating, and hanging its rider out in the opposing lane of traffic.

At Vance & Hines’ request, we let them take the bike back fora couple of days of carb fiddling. And. while the returned Yamaha's carburetion was definitely improved, it was still the worst of this bunch. Adding to our disappointment was an unacceptable level of vibration, which worked its way through the handgrips and threatened to rattle the rider's fingernails loose. On the positive side, w'e liked the brakes on the street, where we had the luxury of easing them on. rather than having to grab the handful necessary on the racetrack.

More enjoyable on the street was the Suzuki. Its ultraslick, carbon-fiber upside-down fork and wide handlebars offered the lightest steering and the greatest sense of feel of any streetbike we've experienced. Power concentration had been shifted higher in the rev range than on the stock Katana, making the bulk of its ponies between 9000 and 13,000 rpm. but the powerband was still very street-usable. Only a slight midrange carburetion glitch and a tingling in the metal, rearset footpegs marred our favorable impression of the Yosh Katana on the street.

But stealing top honors on the street was the Honda. We’ve ridden very few bikes that are more exciting, or more enjoyable. With the exception of a slight stumble just off idle, the Two Brothers CBR felt much like a stocker, only it had lots more power, especially in the midrange, and its handling had been much improved. Smooth, comfortable and near-stock in appearance, it’s a “sleeper” in the truest sense of the word.

As in most forms of competition, there can only be one winner. Too bad. Because if there were an honorable mention for the most-improved, it would have to go to the Yoshimura Suzuki Katana, which was transformed from a plain-Jane sportbike into something that makes us wonder if the much-rumored GSX-R600 is really necessary.

Taking into account such things as streetability and cost effectiveness, the Two Brothers Ffonda CBR600F2 would be a sure winner. Without resorting to the added kick of a nitrous-oxide system, it was a close second in all performance categories, and it is everyday-usable on the street. Building upon the best base bike in the middleweight class, it offers the most bang for your bucks.

But the essence of Built For Speed is that the bike posting the best numbers wins. That being the case, the Vance & Hines Yamaha FZR600 is a runaway victor. Practical, it is not. Inexpensive, it is not. But if you're after a Sundaymorning superbike, a 600 like no other, step right up.

And hold on. Tight.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue