America, THE BEAUTIFUL

Forget the roadster, Zelda, we're going for a ride

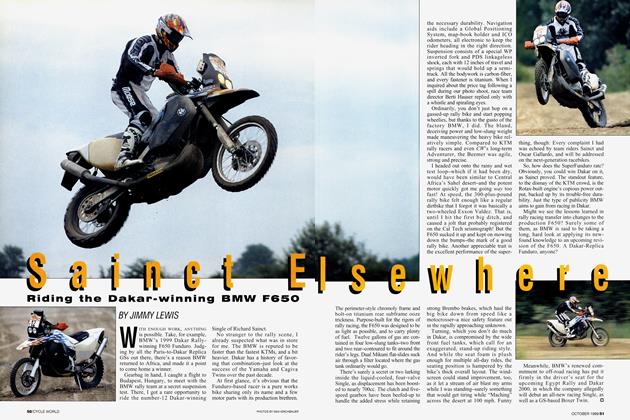

ON A ROSE-COLORED SUMMER AFTERNOON, MY WHITE silk scarf taps gently at my back, keeping time to my reverie of the Jazz Age and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Suddenly, a black Cadillac limousine whizzes past, then screeches to a stop. Its four doors fling open at the same moment, and four young Japanese jump out. Four cameras click, then the quartet bows, smiles and jumps back in the car to disappear up the hill.

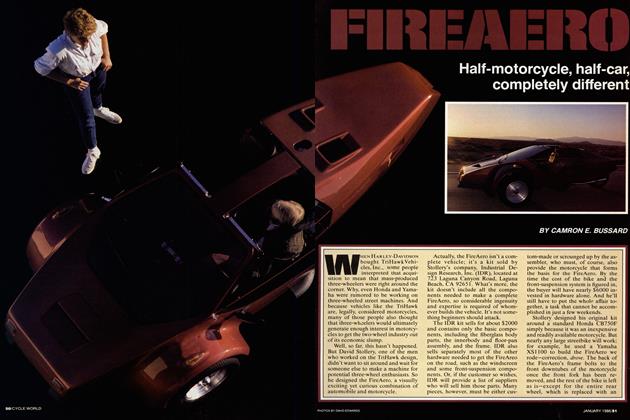

I quickly learn that the 1918 America sidecar rig brings out this kind of spontaneous behavior in people. It's a rare person indeed who ignores this stunningly beautiful replica of a 1918 Harley-Davidson sidecar outfit. Most give in to the seduction of nostalgia, wanting to get close and touch a machine that is a graceful gesture to a simpler time and a not-too-distant past.

Ron Russell is the owner and founder of Vintage Cycle Works, the company that makes and sells 1918 America replica kits. He acknowledges that the bike capitalizes on the power of nostalgia, and he even goes so far as to say that he doesn't sell motorcycles as much as he sells the romantic dreams associated with post-World-War-I America. But he also points out that his bike offers more than just fantasy or easy escapes into the past, and that he uses brand-new Harley-Davidson 883 Sportster engines and braking systems in his kits, making them functional, if not entirely practical, machines.

On the day that I visit Russell's shop in Campbell. California. he is working on his latest customer's dream, a nearly complete 1918 America. All that is lacking is the brasswork and the fiberglass; the engine is mounted and the running gear complete. But even in this stark, unfinished form, the America is singularly beautiful, reflecting the style of an era in which art and function were often one and the same. “After Fm gone," Russell says, “a few of my bikes will still be around. They won't disappear. And someone will look at one of them and wonder what kind of nut took the time to build it."

Russell intended his machine to look as much as possible like the original Harley-Davidson sidecar combo, but he was forced to make slight concessions when it came to the engine and the brakes. The rest of the bike, he insists, is true to the 1918 machine that it emulates.

Even with a quick glance at the unfinished motorcycle in the shop, it's easy to notice a distinct quality of execution in the details of the America. The entire frame is a single structure made of numerous pieces tied together by artful welds, then powder-coated in black. Also getting the black powder coating are the Harley drop-center 21-inch rims, the springer front fork and the handlebar. An especially nice touch are the cutouts in the handlebar that allow the wiring to be routed unseen to the electrical connections next to the handgrips. Then there’s the handmade leather seat that is cut and sewn for him by a retired saddlemaker in Austin, Texas. It exemplifies the type of work—and the type of person —that Russell prefers in his projects. “If someone isn't a little bit of an artist," he says, “they don't get to work with us. We like to think that we’re building little hand-crafted jewels."

You wouldn't expect the level of craftmanship evident on the America to come at bargain-basement prices, and to no one's surprise, it doesn't. The basic kit. which consists of a rolling chassis without an engine, costs $7200. A complete kit goes for $9800. Yes. assembly is required. But Russell explains that, so far. his customers have asked him to build the whole machine, then ship it to them ready to run. Few buyers want a collection of parts that they have to bolt together themselves. Russell says this doesn't surprise him, since the people who have bought his machines have not only been first-time motorcycle owners, but people who see the America as an opportunity to enjoy a unique riding experience, not as a $10,000 collection of nuts and bolts that they get to assemble.

CAMRON E. BUSSARD

Later, when 1 travel to San Francisco for a ride on the Vintage Cycle Works bike, 1 begin to understand what Russell meant when he talked about dreams of the past. Two blocks away from the shop. I spot his partner, Ed Meschal, riding the America. He’s sitting bolt-upright, a long, white scarf billowing out beside him like a thin line of clouds beneath his moustache. He stops to let several pedestrians cross the street, then graciously motions for a car to pass. Even from where I stand, the springer front end looks stiff, as does the authentic hardtail, as Meschal bounces toward me. It strikes me that both the rider and the bike appear to have taken an adventurous spin on H. G. Wells' time machine andjumped off in 1987.

Painted a deep, fire-engine red, the America has bright brass light fixtures, with fittings swollen here and tucked away there on both ends and sides of the machine. The fiberglass fenders, sidecar and false fuel-tank—the actual five-gallon tank is located beneath the seat of the sidecarare nearly flawless, with sensuous surfaces that are smooth to the eyes as well as to the touch. Inside, the car has several small storage compartments tucked away out of sight, and is finished with padded sidepanels and carpeting that exude the same level of craftmanship as the rest of the machine.

As soon as I'm seated in the sidecar, I begin to feel the strength of the past exerting its influence on me—or maybe it's just the bouncing from the stiff springs on the sidecar. But when Meschal and I trade places and I perch atop the rider's seat, I find myself looking out at the most beautiful city in America through the eyes of someone arrived from another era. I, too. start believing that we've traveled back to a simpler time, a time when a motorcycle was not just a vehicle, but an event. And based on the crowds that gather around the bike, the America is nothing if not a rolling historical event.

Despite its modern engine and disc brakes, however, the 1918 America is much more closely related to an antique than it is to anything made today. The way you sit on top of it and the way you feel when you grab onto the sweptback handlebar would seem entirely foreign to modernday riders.

You're even forced to ride the machine in a different way. Although the engine can deliver acceleration and speed about equal to that of a new 883 Sportster, the suspension—or, more correctly, the lack of it—encourages riding at a very gentle pace. What’s more, the steering pulls slightly to the right under acceleration. But it straightens out when you back off, and the machine stops in a straight line regardless of how hard you apply the brakes. Still, even 40 mph is exhilarating, actually feeling more like 80. Cruising between 20 and 30 mph seems about perfect for anyone riding on or in the America, and those speeds also allow the curious to get a good, long look at the machine as you rumble past.

That’s why the 1918 America is for riders who are in no hurry to get anywhere. It’s perfect for anyone with a lot of free afternoons who is eager to ride around in the park. Granted, the America does have a rather limited range of abilities—you're not going to tour cross-country with it, for example—but what it does well, nothing will do better. It isn’t a machine for everyone; it’s for those who can remember—or imagine—a time when a motorcycle was a promise of mystery and excitement waiting just around the next corner. Those people will certainly find an excuse for the simple extravagance of a 1918 America.

Ultimately, Russell is right. He is selling dreams, dreams of the freedom and simplicity of the American spirit of the 1920’s, when all things were possible. And when you ride the 1918 America, you quickly come to believe that anything can happen, anything at all.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

November 1987 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Danforth Problem: Time For Action

November 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

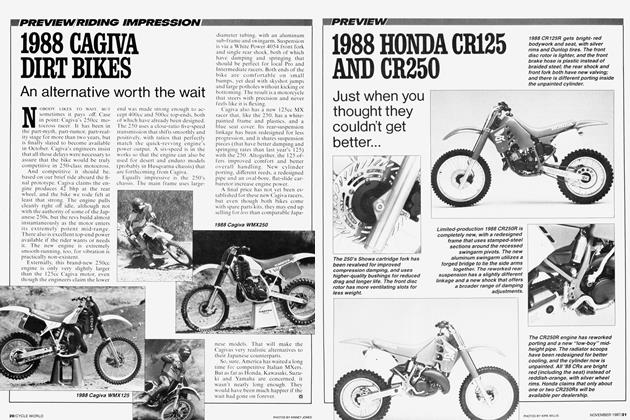

Preview

Preview1988 Honda Cr125 And Cr250

November 1987 -

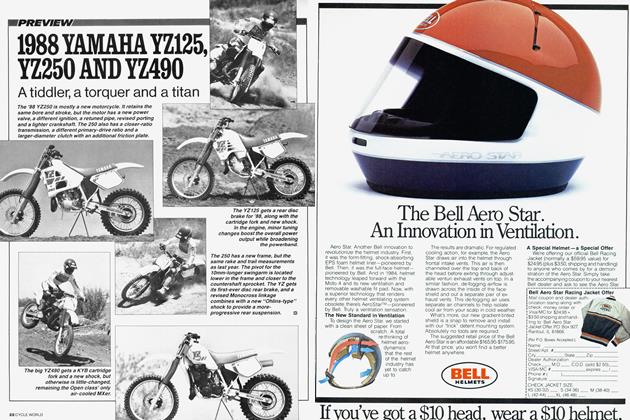

Preview

Preview1988 Yamaha Yz125, Yz250 And Yz490

November 1987 -

Features

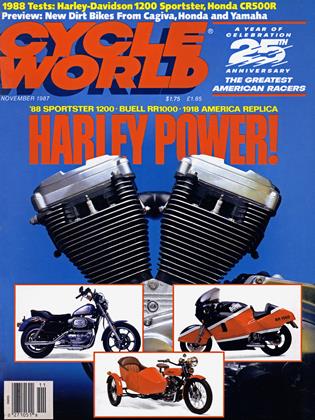

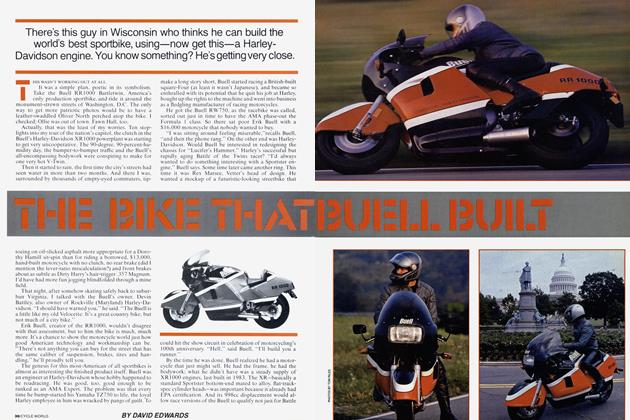

FeaturesThe Bike That Buell Built

November 1987 By David Edwards