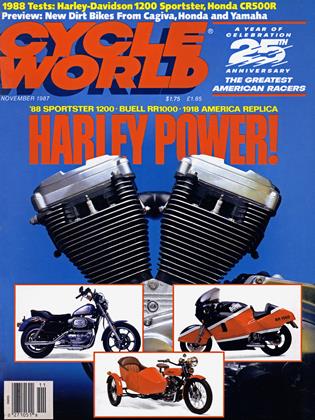

THE BIKE THAT BUELL BUILT

There’s this guy in Wisconsin who thinks he can build the world’s best sportbike, using—now get this—a Harley-Davidson engine. You know something? He’s getting very close.

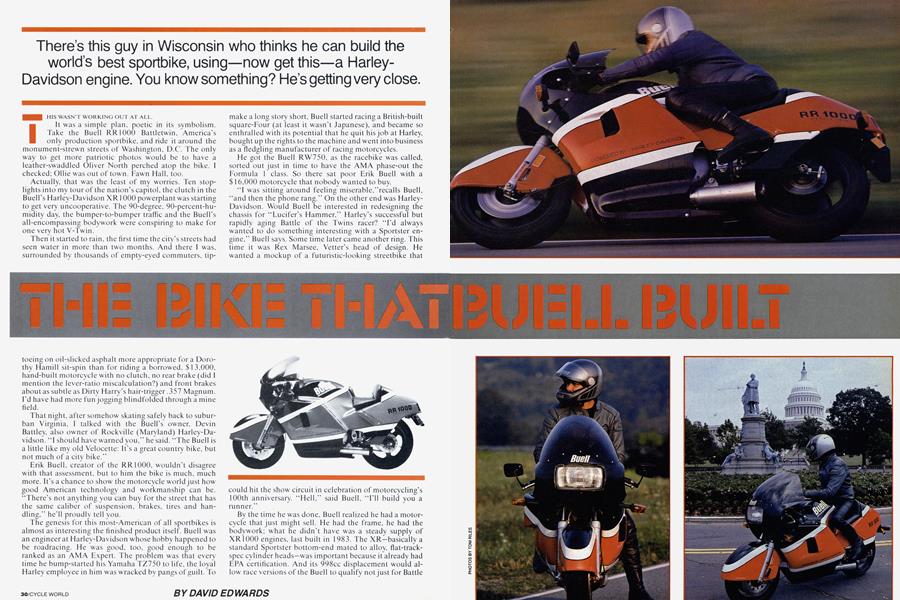

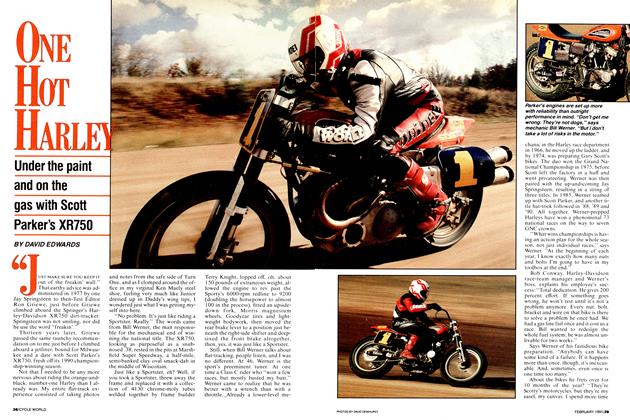

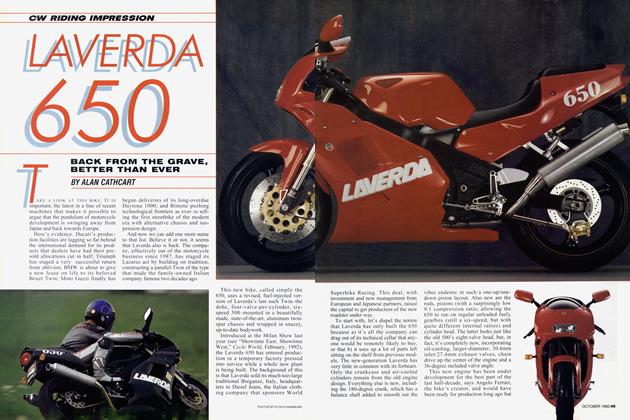

THIS WASN’T WORKING OUT AT ALL. It was a simple plan, poetic in its symbolism. Take the Buell RR1000 Battletwin, America’s only production sportbike, and ride it around the monument-strewn streets of Washington, D.C. The only way to get more patriotic photos would be to have a leather-swaddled Oliver North perched atop the bike. I checked; Ollie was out of town. Fawn Hall, too.

Actually, that was the least of my worries. Ten stoplights into my tour of the nation’s capitol, the clutch in the Buell’s Harley-Davidson XR 1000 powerplant was starting to get very uncooperative. The 90-degree, 90-percent-humidity day, the bumper-to-bumper traffic and the Buell’s all-encompassing bodywork were conspiring to make for one very hot V-Twin.

Then it started to rain, the first time the city’s streets had seen water in more than two months. And there I was, surrounded by thousands of empty-eyed commuters, tiptoeing on oil-slicked asphalt more appropriate for a Dorothy Hamill sit-spin than for riding a borrowed, $13,000, hand-built motorcycle with no clutch, no rear brake (did I mention the lever-ratio miscalculation?) and front brakes about as subtle as Dirty Harry’s hair-trigger .357 Magnum. I’d have had more fun jogging blindfolded through a mine field.

That night, after somehow skating safely back to suburban Virginia, I talked with the Buell’s owner, Devin Battley, also owner of Rockville (Maryland) Harley-Davidson. “I should have warned you,” he said. “The Buell is a little like my old Velocette: It’s a great country bike, but not much of a city bike.”

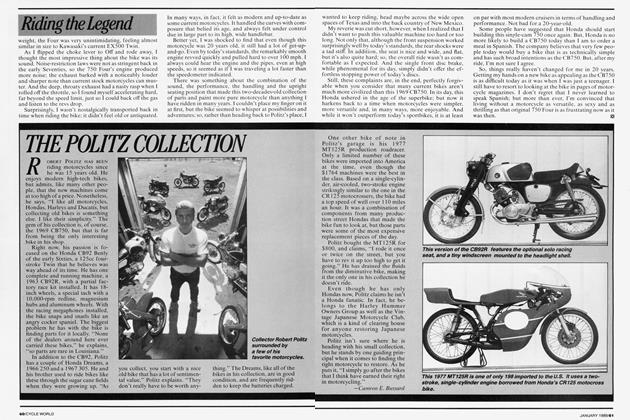

Erik Buell, creator of the RR1000. wouldn’t disagree with that assessment, but to him the bike is much, much more. It’s a chance to show the motorcycle world just how good American technology and workmanship can be. “There’s not anything you can buy for the street that has the same caliber of suspension, brakes, tires and handling,” he’ll proudly tell you.

The genesis for this most-American of all sportbikes is almost as interesting the finished product itself. Buell was an engineer at Harley-Davidson whose hobby happened to be roadracing. He was good, too, good enough to be ranked as an AMA Expert. The problem was that every time he bump-started his Yamaha TZ750 to life, the loyal Harley employee in him was wracked by pangs of guilt. To make a long story short, Buell started racing a British-built square-Four (at least it wasn’t Japanese), and became so enthralled with its potential that he quit his job at Harley, bought up the rights to the machine and went into business as a fledgling manufacturer of racing motorcycles.

He got the Buell RW750, as the racebike was called, sorted out just in time to have the AMA phase-out the Formula 1 class. So there sat poor Erik Buell with a $ 16,000 motorcycle that nobody wanted to buy.

“I was sitting around feeling miserable,’’recalls Buell, “and then the phone rang.” On the other end was HarleyDavidson. Would Buell be interested in redesigning the chassis for “Lucifer’s Hammer,” Harley’s successful but rapidly aging Battle of the Twins racer? “I’d always wanted to do something interesting with a Sportster engine,” Buell says. Some time later came another ring. This time it was Rex Marsee, Vetter’s head of design. He wanted a mockup of a futuristic-looking streetbike that could hit the show circuit in celebration of motorcycling’s 100th anniversary. “Hell,” said Buell, “I'll build you a runner.”

By the time he was done, Buell realized he had a motorcycle that just might sell. He had the frame, he had the bodywork; what he didn’t have was a steady supply of XR1000 engines, last built in 1983. The XR—basically a standard Sportster bottom-end mated to alloy, flat-trackspec cylinder heads—was important because it already had EPA certification. And its 998cc displacement would allow race versions of the Buell to qualify not just for Battle of the Twins (now Pro Twins) competition, but also for Superbike racing, where the rules allow lOOOcc Twins to run against 750cc multi-cylinder machines.

DAVID EDWARDS

This is where Devin Battley got involved. Battley the Harley dealer liked the idea of having the distinctive RR1000 on his showroom floor; but Battley the Battle of Twins roadracer (he finished third in the national point standings in 1984, on a BMW) was almost bubbling over with anticipation, so much so that he gave Buell a deposit for the very first production Battletwin. To make sure that production became reality, Battley smuggled Buell into the 1985 Harley-Davidson dealers’ meeting, which happened to be on a cruise ship bound for the Bahamas. By the time the ship docked, almost 20 dealers had said they’d be interested in carrying the RR1000; and Harley CEO Vaughn Beals, a man who apparently appreciates chutzpah, had gotten behind the project as well. Buell had his engines and was back in the bike-building business.

It should come as no great revelation that the bike Buell built is not very far removed from a roadracer. That point was driven home as I backed Battley’s RR 1000 (serial No. 001) out of his shop, banging my hands on the fuel tank and fairing edges as I worked the clip-ons through their limited steering lock. It’s a long, low reach to those clipons, as well, although the solo seat is surprisingly wellpadded and the footpeg position not all that cramped. “I don’t like sitting on a motorcycle,” explains Buell. “I would never build anything like that.”

That kind of single-track approach to building his motorcycle is evident in the RRlOOO’s componentry. Dymag wheels, Pirelli radiais. Lockheed brake calipers, 42mm Marzocchi MIR fork. Works Performance shock, Supertrapp exhaust, all of which contribute to the Battletwin’s lofty asking price of $ 12,999. Still, at a time when Softail Custom Harley-Davidsons are pushing 10 grand, three thousand more for a limited-production creation like the Buell doesn’t seem out of line. Currently, Buell and his five-man work team are turning out one bike a week in their Wisconsin shop (Buell Motor Co., S64 W31751 Highway X, Mukwonago, WI 53149). About 15 RR 1000s are in owners’ hands now, with engines available for another 40.

It doesn’t bother Buell that those XR1000 engines aren’t especially well-suited to the role of a powerplant for a world-beating sportbike. He knows that with just 70 horsepower on tap, a stock RR1000 will top-out at less than 130 miles per hour. He knows that the long-throw, four-speed transmission couldn’t execute a snick-snick gearchange if its life depended on it. He knows that the 36mm Dell’Orto pumper carbs have the stiffest return springs in all of motorcycling, making delicate throttle control all but impossible.

‘Tve never been a proponent of great amounts of horsepower for street use,” Buell explains. “With the RW750,1 built a motorcycle that could annihilate just about anything. That kind of power has no place on the street; it would be terrifying. I’d rather rely on light weight, handling and streamlining.”

My evaluation of the Buell’s handling took place out in the rolling hills of the Virginia countryside, where the bike could cut loose and air itself out. The first thing you notice—or rather don't notice—is vibration. Suspended on three rubber biscuits and tied into the Buell-designed frame by four Heim-jointed struts, the engine doesn’t pass on much of its considerable shaking to the rider.

What it does pass on is a sure-footed confidence, a directness that responds well to firm inputs. Clearly, this is a rider’s motorcycle. Unfortunately, my time with the RR 1000 was cut short by the balky clutch (later traced to a damaged clutch cable that wouldn't allow full disengagement) and a shock that had lost its nitrogen charge and, hence, much of its damping.

Still, it's clear that the handling is there. And there's the promise of an even better Buell in the offing. The next series of bikes will use the Sportster 1200 Evolution motor, a much more hospitable creature than the rough-edged XR1000. And since the 1200 is too big for race use, it's likely that the Evolution-engined bikes will be stretched slightly, enough to accommodate a dual seat. But even now, Buell is looking beyond those bikes.

“I'd like to stay closely tied with Harley. As it is, though, the XR 1000 engine weighs 210 pounds, and the first thing I have to do is bolt on a 12-pound casting to mount the swingarm. So what I want to do is convince them to build a 150-pound engine with an integral swingarm pivot.”

A Buell built around that engine? How good would it be? Will it happen?

If it does, the line forms right here.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

November 1987 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1987 -

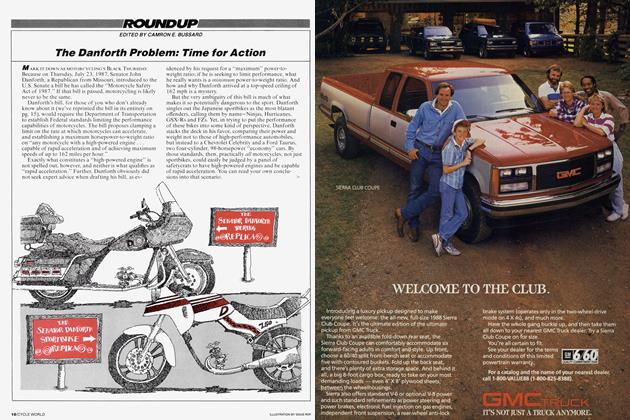

Roundup

RoundupThe Danforth Problem: Time For Action

November 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

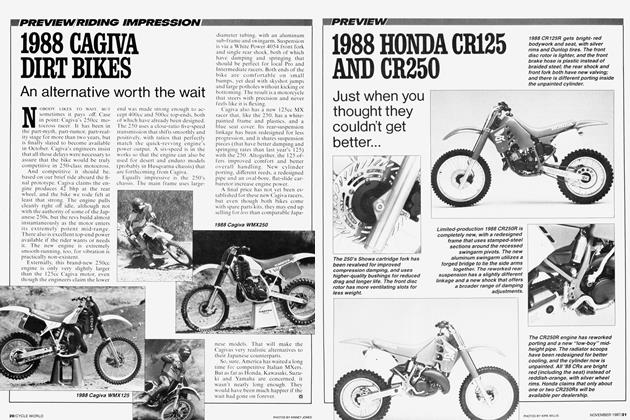

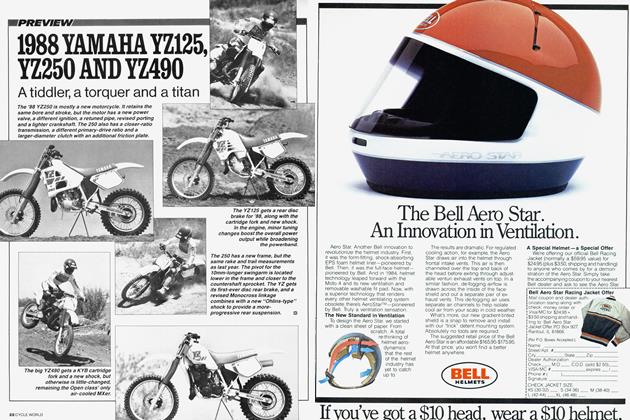

Preview

Preview1988 Honda Cr125 And Cr250

November 1987 -

Preview

Preview1988 Yamaha Yz125, Yz250 And Yz490

November 1987 -

Features

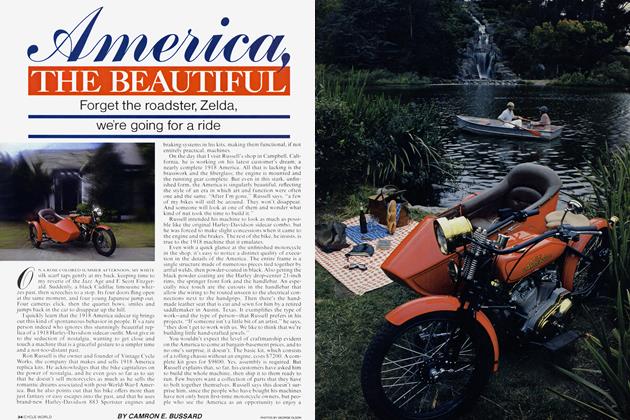

FeaturesAmerica, the Beautiful

November 1987 By Camron E. Bussard