The Danforth Problem: Time for Action

ROUNDUP

CAMRON E. BUSSARD

MARK IT DOWN AS MOTORCYCLING’S BLACK THURSDAY. Because on Thursday, July 23, 1987, Senator John Danforth, a Republican from Missouri, introduced to the U.S. Senate a bill he has called the “Motorcycle Safety Act of 1987.” If that bill is passed, motorcycling is likely never to be the same.

Danforth’s bill, for those of you who don’t already know about it (we’ve reprinted the bill in its entirety on pg. 15), would require the Department of Transportation to establish Federal standards limiting the performance capabilities of motorcycles. The bill proposes clamping a limit on the rate at which motorcycles can accelerate, and establishing a maximum horsepower-to-weight ratio on “any motorcycle with a high-powered engine . . . capable of rapid acceleration and of achieving maximum speeds of up to 162 miles per hour.”

Exactly what constitutes a “high-powered engine” is not spelled out, however, and neither is what qualifies as “rapid acceleration.” Further, Danforth obviously did not seek expert advice when drafting his bill, as evidenced by his request for a “maximum” power-toweight ratio; if he is seeking to limit performance, what he really wants is a minimum power-to-weight ratio. And how and why Danforth arrived at a top-speed ceiling of 162 mph is a mystery.

But the very ambiguity of this bill is much of what makes it so potentially dangerous to the sport. Danforth singles out the Japanese sportbikes as the most blatant offenders, calling them by name—Ninjas, Hurricanes, GSX-Rs and FZs. Yet, in trying to put the performance of these bikes into some kind of perspective, Danforth stacks the deck in his favor, comparing their power and weight not to those of high-performance automobiles, but instead to a Chevrolet Celebrity and a Ford Taurus, two four-cylinder, 98-horsepower “economy” cars. By those standards, then, practically all motorcycles, not just sportbikes, could easily be judged by a panel of safetycrats to have high-powered engines and be capable of rapid acceleration. You can read your own conclusions into that scenario.

Perhaps as important as the bill itself is the hyperbolic tone of the short speech Danforth made when introducing the bill to the Senate. During that speech, he used the term “killer motorcycles” or "killer cycles” no less than seven times. He supplied no breakdown of displacement categories and accident statistics, leaving the wrongful impression that high-performance bikes are the only ones involved in motorcycle deaths. Neither did he acknowledge the large percentage of deaths that were the fault of someone other than the rider of the motorcycle, nor did he mention the speed at which the average motorcycle accident occurs, which is certainly not 162 mph or anything remotely close to it. So while he condemns the Japanese manufacturers for “corporate irresponsibility” in marketing high-performance bikes in the U.S., he himself shows an unforgivable level of irresponsibility by misconstruing the truth in an attack on an industry he obviously knows very little about.

Many people believe that the real driving force behind this legislation is the IIHS (Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, the political lobbying arm of the insurance industry), and that Danforth simply is responding to their ongoing attempts to force a ban of high-performance motorcycles. That contention seems to have at least some basis in truth, for during the course of his speech, Danforth frequently cited IIHS statistics and made almost direct quotes from IIHS documents.

Be that as it may, there is more to this bill than simply an escalation in the insurance industry's assault on motorcycling. Danforth is known in political circles as a “protectionist,” someone who is never afraid to jump into the breach when the balance of trade between U.S.made and imported goods tilts too far in favor of foreign interests. What’s more, Danforth’s legislative director, Susan C. Schwab, is one of Capitol Hill’s most influential and aggressive experts on trade issues. Schwab has been accused of being the prime-mover behind what is popularly called “Japan-bashing,” a term used to describe the government’s hard-nosed attempts to clamp down on Japan for failing to maintain an acceptable trade balance with the U.S.

Indeed, in Japan, Danforth’s bill is seen largely as a trade measure—so much so that Japanese automobile companies have already begun pressuring their motorcycle-manufacturing brethren to ease up on big performance bikes and to lower horsepower output. This apparently would take some of the heat off the muchlarger Japanese automobile industry; but at the same time, it would relegate motorcycles to mere whippingboy status in the international trade wars.

So in the end, Danforth's bill appears to have its roots in two different areas: safety, perhaps as defined by the IIHS; and problems with one of this country’s largest trade partners.

But the bill is by no means exclusive to Japanese motorcycles. Based on Danforth’s use of 98-horsepower cars as a point of reference, almost any sort of Federal performance standard could very well affect all full-sized motorcycles, be they Hondas or Harleys or BMWs, sportbikes or touring bikes or cruisers. If that doesn’t invoke the ire of all motorcyclists—not just those who ride high-performance models—and spur them into affirmative action, nothing will.

After its submission, the bill was assigned to the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, which then handed it down to a Subcommittee on Consumers, where the issues will be studied before the bill is returned to the main committee. The good news is that the bill is likely to remain with the sub-committee for a while, allowing the motorcycling community enough time to mount serious opposition. The bad news is that this sub-committee is headed by Senator Albert Gore, a Democrat from Tennessee who already is a renowned ATV-hater. Motorcyclists in that state would do well to write the Senator and let him know how they feel about Danforth’s bill.

To assist in that regard, we have printed the names and addresses of the members of these committees in the hopes that all of you who know how to operate a pencil will write and voice your opinions about this proposed legislation. Obviously, if your state has a senator on either committee, you should write him or her. But even if your senator is not on these committees, you should write him or her anyway and let your feelings be known.

Because if this bill ever gets out of committee, it will then go to the Senate floor where your senator’s vote will help determine whether or not it comes that much closer to becoming law'. But it’s better not to let it get that far; a bill is its weakest while in the sub-committee, and a groundswell of opposition early-on is the most effective way to fight it.

Beyond a doubt, riders in California are in a position to exert considerable influence in this matter. Danforth claims that the problem is most severe in that state; and California Senator Pete Wilson is a member of the committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation. So if Wilson does not lend the bill his support, it will be difficult for the measure to gain the credibility it needs to succeed.

But that will happen only if people exercise their democratic rights and stand up for what they believe in. And if there ever was a time for individual and collective action by all motorcyclists, it is now, for never before has the sport faced such a potentially serious threat. You can’t wait for the AMA, the MIC or the individual manufacturers to fight this fight for you. After all, those are just companies or organizations; they don’t vote.

You, however, are a constituent. You put politicians in office; and through the power of your vote, you have the ability to remove them from office. More than any other moment in motorcycling’s history, now is the time to remind your senator of that power.

Senator Danforth's speech introducing the "Motorcycle Safety Act of 1987"

Mr President, in 1984, the Japanese began selling what can only be described as “killer motorcycles” in this country. These are racing bikes that were developed for use on a track, but they are being driven on our streets. From a dead stop, one of these “super bikes” can accelerate to 60 mph by the time it reaches the other side of a city intersection. It takes one of those killer cycles 2.7 seconds to reach this speed. Top speeds for these bikes range up to 162 mph. Some of these 400 to 600 pound motorcycles have well over 100 horsepower. For comparison, a four-cylinder Chevrolet Celebrity weighs 2,705 pounds and has 98 horsepower. A four-cylinder Ford Taurus weighing 2,886 pounds has only 98 horsepower.

Mr. President, the marketing of these killer cycles is a lesson in corporate irresponsibility. They are made by Japanese manufacturers under names such as the Kawasaki Ninja, Honda Hurricane, Suzuki GSX-R. and Yamaha FZ. The ads are directed at teenage males. A typical one is Honda’s slogan-“0 to 55 faster than you can read this.”

Mr. President, the combination of these racing machines and young inexperienced riders is deadly. In southern California, young riders are racing super bikes on the public streets. Down a narrow, twisting canyon road such as Mulholland Drive near Los Angeles, packs of six or more riders fight for position in the left lane. These riders frequently run head on into oncoming traffic. The police do not chase these killer cycles for fear of crashing their patrol cars or motorcycles. Unfortunately, this problem is spreading to other areas, particularly military bases. For example, in November 1986, near the Orlando, Florida, Naval Training Center, a speeding cyclist killed two teenagers.

Mr. President, this problem is particularly galling because the Japanese have virtually banned the sale of these killer cycles in their own country because of safety concerns. According to the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, in Japan it is virtually impossible to get a license to operate a motorcycle with more than a 400 cubic centimeter (cc) engine. Only one in 20 of the applicants who pays an expensive application fee manages to get a license. In addition, the Japanese manufacturers have an unwritten agreement with the Japanese government not to sell any motorcycles with over 750cc in Japan.

Mr. President, this is analogous to selling Indy racers to teenagers barely old enough to ha,ve a license and then turning them loose on the public streets to “play.” Law enforcement cannot stop these killer cycles; they are too fast. There is only one way to stop them and that is to limit the power and speed of super bikes sold for street use in this country.

Mr. President, I am introducing today the “Motorcycle Safety Act of 1987” to end this danger. It would require the Secretary of Transportation to develop safety standards that will eliminate the hazards of these killer cycles. My bill would require the Secretary to examine a series of limitations on this new breed of racing-type motorcycles. One limit that must be considered is on acceleration. Zero to 60 in 2.7 seconds on city streets is too dangerous. The bill would also require consideration of limits on the weight to horsepower ratios of super bikes.

Finally, my bill would require the Secretary of Commerce to report to Congress on the extent to which foreign manufacturers are restricted by their governments from selling motorcycles in their home countries which they are selling in our country. Mr. President, I ask unanimous consent that this bill be printed in the Congressional Record.

Mr. President, I urge my colleagues to support this legislation. The public safety cannot tolerate the continued use of these “rockets” on our public streets.

100th Congress l st Session

S B. I 536

IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES

Mr. DANFORTH introduced the following bill; which was read twice and referred to the committee.

A BILL

To require the Secretary of Transportation to promulgate rules regarding the safe operation of certain rapid acceleration motorcycles, and for other purposes.

Be it resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, that this act may be cited as the “Motorcycle Safety Act of 1987.”

Sec. 2. The Congress finds that—

( l ) In 1985, over 4,700 individuals were killed in accidents involving motorcyles, and

(2) in recent years, the competition among certain manufacturers to produce and sell motorcycles equipped with highpowered engines and engineered and designed to enable such motorcycles to be capable of rapid acceleration and of achieving maximum speeds of up to 162 miles per hour has posed safety hazards to the operators of such motorcycles and other individuals while such motorcycles are used on public highways, roads, and streets and in other public areas.

Sec. 3. Part A of Title l of the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966 ( l 5 U.S.C. 1391 et seq.) is amended by adding at the end the following:

“Sec. 126. (a) The Secretary shall initiate (not later than 26 days after the date of enactment of the Motorcycle Safety Act of 1987) and complete (not later than one year after the date of enactment of the Motorcycle Safety Act of 1987) a rulemaking to establish a Federal motor vehicle safety standard applicable to any motorcycle equipped with a high-powered engine and engineered and designed to enable such motorcycles to be capable of rapid acceleration and of achieving maximum speeds of up to 162 miles per hour. Notwithstanding section 103(f) (3) of this Act, it shall be the purpose of such rulemaking to eliminate, to the extent possible, the hazards posed to operators of such motorcycles and other individuals while such motorcycles are used on public highways, roads, and streets, and in other public areas.

“(b) In promulgating a rule under subsection (a) of this section, the Secretary shall consider, among other methods—

“( 1 ) the establishment of maximum achievable rate of acceleration for such motorcycles: and

“(2) the establishment of a maximum horsepower-to-weight ratio for such motorcycles.

“(c) Rules promulgated under subsection (a) of this section shall apply to any such motorcycle offered for sale or sold on or after July 23, 1987.”

Sec.4. Not later than 60 days after the date of enactment of this Act. the Secretary of Commerce shall conduct a study as to the extent to which, if any, foreign countries impose safetyrelated restrictions on the manufacture or sale of motorcycles which their manufacturers are attempting to market or are marketing in the United States, and the reasons for the imposition of such restrictions. The Secretary of Commerce shall transmit the results of such study to the Congress not later than one year after the date of enactment of this Act.

Senators on the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation

Brock Adams D-Washington, 51 3 Hart Senate Office Bldg. Washington, DC 20510 (202) 224-2621 Lloyd Bentsen D-Texas 703 Hart Senate Office Bldg. Washington, DC 20510 (202) 224-5922 John Breaux D-Louisana 104 Dirksen Senate Office Bldg. Washington, DC 20510 (202) 224-4623 John Danforth R-Missouri 497 Russell Senate Office Bldg. Washington, DC 20510 (202) 224-6154 James Exon D-Nebraska 330 Hart Senate Office Bldg. Washington, DC 20510 (202) 224-4224 Wendell Ford D-Kentucky 173A Russell Senate Office Bldg Washington, DC 20510 (202) 224-4343

Albert Gore, Jr. D-Tennessee 393 Russell Senate Office Bldg. Washington, DC 20510 (202) 224-4944 Ernest Hollings D-South Carolina 125 Russell Senate Office Bldg. Washington, DC 20510 (202) 224-6121 Daniel lnouye D-Hawaii 722 Hart Senate Office Bldg. Washington, DC 20510 (202) 224-3934 Nancy Kassebaum RKansas 302 Russell Senate Office Bldg. Washington, DC 20510 (202) 224-4774 Robert Kasten, Jr. R-Wisconsin 110 Hart Senate Office Bldg. Washington, DC 20510 (202) 224-5323 John Kerry D-M assachusetts 362 Russell Senate Bldg. Washington, DC 20510 (202) 224-2742

John McCain R-Arizona 210 Hart Senate Office Bldg. Washington, DC 20510 (202) 224-2235 Bob Packwood R-Oregon 259 Russell Senate Office Bldg. Washington, DC 20510 (202) 224-5244 Larry Pressler R-South Dakota 407A Russell Senate Office Bldg. Washington, DC 20510 (202) 224-5842 Donald Riegle Jr. D-Michigan 105 Dirksen Senate Office Bldg. Washington, DC 20510 (202) 224-6472 John Rockefeller IV D-West Virginia 241 Dirksen Senate Office Bldg. Washington, DC 20510 (202) 224-6472 Ted Stevens R-Alaska 522 Hart Senate Office Bldg. Washington, DC 20510 (202) 224-3004

Paul Trible Jr. R-Virginia 517 Hart Senate Office Bldg. Washington, DC 20510 (202) 224-4024

Pete Wilson R-California 720 Hart Senate Office Bldg. Washington, DC 20510 (202) 224-3841

Senate Sub-Committee on Consumers

Albert Gore D-TN Wendell Ford D-KY John Breaux D-LA Bob Kasten R-WI John McCain R-AZ

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

November 1987 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1987 -

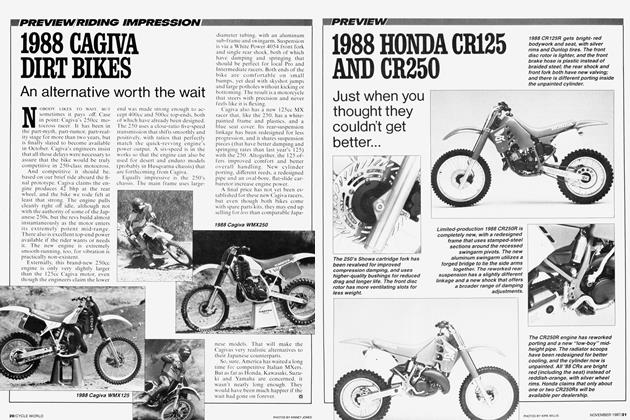

Preview

Preview1988 Honda Cr125 And Cr250

November 1987 -

Preview

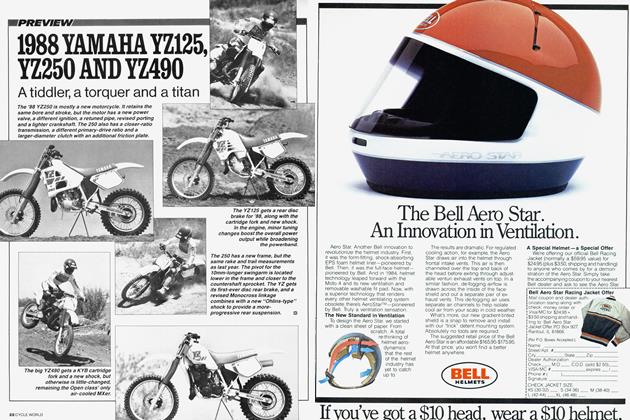

Preview1988 Yamaha Yz125, Yz250 And Yz490

November 1987 -

Features

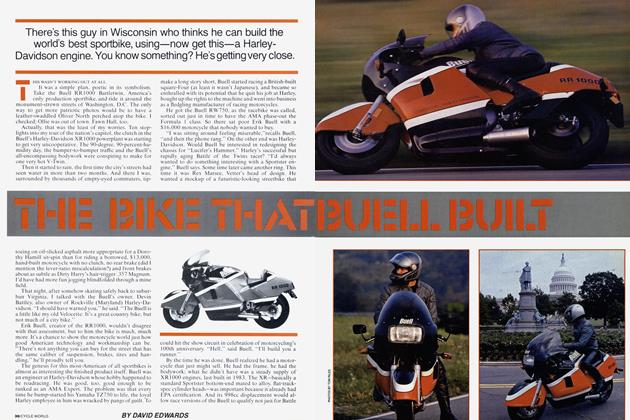

FeaturesThe Bike That Buell Built

November 1987 By David Edwards -

Features

FeaturesAmerica, the Beautiful

November 1987 By Camron E. Bussard