The perfect motorcycle

ROUNDUP

CAMRON E. BUSSARD

EVER WISHED FOR THE PERFECT MOTORCYCLE. ONE THAT did everything you asked of it, no matter what the task?

If you’re anything like all of us here at Cycle World, you’ve thought about such a mythical motorcycle quite often. But again, if you’re like us, you usually end up believing that your perfect bike will forever remain a figment of your imagination, that you’ll never experience the unspoiled joy of riding a motorcycle custom-built to your exact wants and needs.

But, everyone can dream—including motorcycle-magazine editors. Even though we’re fortunate enough to be able to ride just about every motorcycle that comes down the pike, we still have our own personal dreambikes, idealistic machines we think would suit our very specific requirements right down to the ground. This isn’t to say that we find the current crop of motorcycles desperately lacking, or that we think we're better designers than the ones who work for the manufacturers; and we're not necessarily suggesting that any company actually build such machines—although if someone did, we’d be the first in line to buy them. Nope, our dreambikes are exactly what the name implies: our personal visions of motorcycling perfection. Besides, we know that when it comes to motorcycles, one rider’s perfection is another rider’s pile of worthless parts. Potentially, there are as many “perfect” motorcycles as there are riders.

Even among this staff there is a wide range of differences in personal motorcycling ideals. We all like and ride all kinds of motorcycles, but each of us has a preference for at least one particular type of riding. So, when we think and talk about ideal motorcycles, our individual passions for our favorite kind of riding are reflected in the machinery we envision.

Senior Editor Ron Griewe, for example, loves the desert, and has been riding and racing in it almost weekly since the early Seventies. He prefers Open-class dirt bikes, but always has to modify them to meet his basic desert requirement: the ability to cover relatively long distances at high speeds with the utmost in comfort and control. Thus, his perfect bike is powered by a fourstroke Single, perhaps the Husky 510 engine, in a lightweight chassis that would yield a total weight of under 220 pounds. With a works-quality suspension, the end result would be a powerful, dependable, ultra-light desert weapon that would allow Griew'e to cover vast distances with minimum physical abuse, but that still would be versatile enough for more-casual trail rides.

My idea of the perfect motorcycle is a streetbike similar in purpose to Griewe’s long-range desert bike. I prefer day trips on all types of roads, from interstates to twisty two-lanes, but do most of my riding around town. I'm not a canyon-carver by any means, but I still like a bike that goes and turns and stops without a lot of effort. That’s why I want an engine like the Katana 1 100’s at the heart of this machine. I prefer inline-Fours anyway, and have fallen in love with this particular engine’s incredibly wide power spread. But the rest of the 1 100 Katana is too large and heavy for my tastes, so Fd like a lighter and more nimble bike, preferably one that weighs in under 500 pounds. A seating position similar to that of a Honda Nighthawk S 700 is essential, however.

Executive Editor Steve Anderson also thinks that the perfect bike should combine comfort and elegance in a sporting chassis. As he puts it, “I want a sport-oriented bike with a standard motorcycle configuration." Such a motorcycle already exists in Honda’s new 650cc Hawk GT, but Anderson wants a larger engine in his dreambike. What he wants, in effect, is an 1 lOOcc Hawk GT. Its big, loping V-Twin engine would produce massive low-end power, yet be light and narrow. And Anderson insists that the perfect bike also be comfortable for two-up riding.

Editor Paul Dean, on the other hand, treasures horsepower. Not just indiscriminate high engine output, but muscle that feels and sounds raw and untamed. And when it comes to that kind of soul-stirring thump and whump. Dean thinks the Yamaha V-Max engine is impossible to beat. So, the perfect bike for him would be molded around that engine. But because the V-Max motor is quite heavy and uses shaft final drive, Dean wants the power-producing part of the engine coupled to lighter cases and driveline components, including chain drive, to help him wind up with a sport-touring machine that is as light and as sporty as possible. He isn’t after a V-Max-powered GSX-R by any means, but rather a highpowered, good-handling machine that can comfortably cover long distances on twisty roads, and that feels and sounds as exciting to ride as it actually is.

Curiously enough. Dean, Anderson and I all have similar purposes in mind with our bikes—sport-touring— but each has a slightly different slant on how best to get the job done. And while our aforementioned perfect bikes-and Ron Griewe’s, as well-all seem fairly reasonable and even buildable, Feature Editor David Edwards and Managing Editor Ron Lawson both require their perfect bikes to perform almost unreasonable tasks. Both have ideas that sound irresistible on paper, but that would be nearly impossible to turn into reality.

Lawson rides, on the average, one motocross race a weekend and one enduro a month. He doesn’t want to have two different bikes to prep and maintain, so he thinks the perfect machine should be able to win at the local MX track, then be ridden to first place at the next enduro. For that task, he envisions a Honda CR350R, a bike that handles and feels like a CR250R, but has

enough horsepower to outrun the competition in Openclass motocross. Considering that motocross bikes already are perhaps motorcycling’s most sophisticated and specialized machines, Lawson’s perfect bike asks its designer to invent some technological wizardry that has eluded all the manufacturers so far.

But that’s nothing compared with David Edwards’ perfect motorcycle. Edwards fondly remembers the good old days of motorcycling when you owned just one bike and did everything with it. If you wanted to go roadracing, you bolted on a pair of clip-on handlebars and sticky tires. If you wanted to ride an enduro, you switched to higher handlebars, knobby tires and trail gearing, then headed for the hills. Road riding? Just slip on some lights and street tires and be on your way. So Edwards’ perfect bike would have to do anything his heart desired on any given day. “It wouldn’t be a dualpurpose bike,” he says, “but an ¿///-purpose bike. I want it to do everything.” That includes roadracing, off-road exploring and sport-touring. And he’d like that machine to be powered by a 650cc or 750cc V-Twin, making his perfect bike sound something—but not exactly—like the Honda Transalp currently sold in Canada and Europe.

As you can see, most of our dream machines could, for the most part, become production motorcycles. But the chances are slim that any of them, with the possible exception of Anderson’s bike, will see the light of day in the near future. But that’s okay with us; we really don’t want our ideal bikes rolling off the assembly lines. After all, how exciting would the perfect motorcycle be if everyone you saw was riding one? —Camron E. Bussard

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

March 1988 By Steve Anderson -

Departments

DepartmentsLeanings

March 1988 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1988 By Hector Cademartori -

Roundup

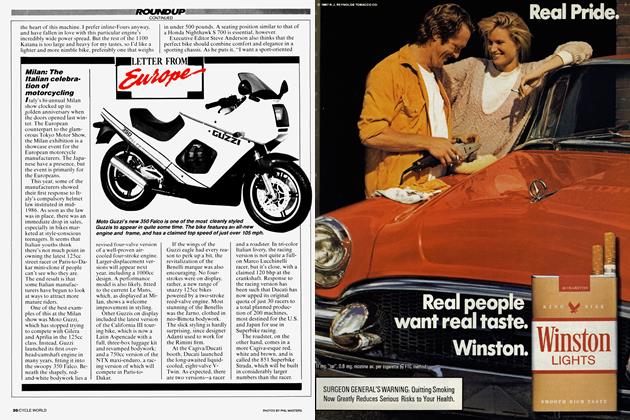

RoundupLetter From Europe

March 1988 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupDestinations

March 1988 By David Edwards -

Features

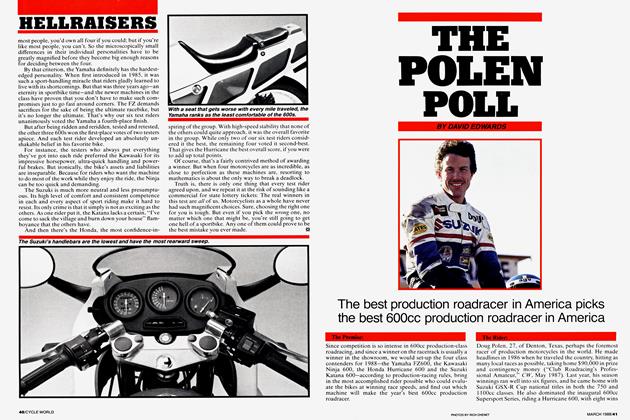

FeaturesThe Polen Poll

March 1988 By David Edwards