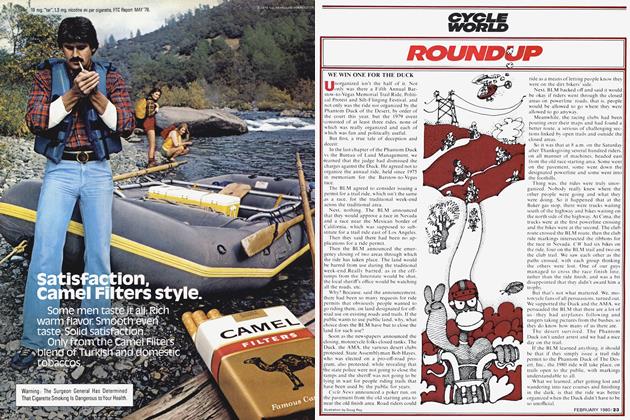

We have ways to make you safe...

The German Government's Approach to Motorcycle Safety May Be a Frightening Look Into Our Own Future.

John Ulrich

If you've ever worried about what the "safety" concerns of NHTSA chief Joan Claybrook and the mechanical meddling of the EPA could lead to, imagine this scenario:

You wish to change the handlebars on your 1973 Honda CB750. The bars you buy at your local motorcycle shop are approved by the government for your year and model. After installing the bars, you head for a nearby government office, where you pay a fee and present the proof of approval sheet you were given when you bought the bars. On that 8'/2 by 11 in. sheet are quarter-sized reproductions of seven pages of technical reports from the approving agency, including blueprints of the bars, installation diagrams, and the date and location of government testing and approval of the handlebars. An inspector takes the technical information and checks your motorcycle. Once satisfied, he fills out a form and you again join a line inside the office, waiting for a clerk to make an official notation in your bike’s registration, a notation stating that the non-standard handlebars mounted on your motorcycle have been inspected and approved. It sounds like a far-fetched nightmare, but it isn’t. Instead, it’s a fact of life in West Germany. Under West German law, new motorcycle models must be approved by the government before release. After reviewing the design and the results of tests completed by the manufacturer, the government certifies the machine as being approved in its submitted form, and the cost of the certification process is borne by the manufacturer. If any part listed in the law is changed from stock, it must be inspected and approved by the government, at the motorcycle owner’s expense. Only approved replacement parts are allowed.

The implications are far reaching and expensive for anybody who wants to add parts or accessories to his motorcycle.

As the government sees it, a motorcycle as submitted for approval by the manufacturer is certified safe in the stock condition. That is, the frame is rigid enough for the power output of the engine, the brakes powerful enough for the machine’s speed capabilities (remember, on West German Autobahns, there is no speed limit). A bike which is safe at 100 mph, the government reasons, may not be safe at 135 mph, endangering both the rider and the general public.

If a rider installs a camshaft or big bore kit in his bike, he is referred to an authorized testing firm, which removes the engine and puts it on a dynamometer to measure horsepower, a process which can typically cost the bike owner 1000 Deutsche Marks (about $567). Armed with the results of the dyno test, government inspectors decide whether or not the bike can theoretically handle the extra power. If they decide it can, then they ride the bike at a test track to determine actual top speed, frame and brake performance— at a cost to the owner of 45 DM (about $25) per hour for testing and calculating. If it happens that a spell of foul weathercommon in Germany—delays testing for a few weeks or a few months, the owner is simply out of luck, since he can’t ride the bike on the public roadways until it is approved in its modified form. And if the government experts decide that the frame can’t handle the extra power, well, the owner is again out of luck, since the modifications won’t be approved.

The list of accessories which require inspection and certification is exhaustive, and the only way an owner can avoid the hassle and expense of an encounter with the government inspectors is to use only accessories brought through the certification process by the motorcycle manufacturer. For example, owners of certain BMW models can install BMW fairings on their bikes without needing an inspection, since BMW presented those models to the government for certification both with and without that fairing. But obviously, BMW is not going to go to the trouble of having, say, a Vetter fairing approved: somebody might buy a Vetter fairing instead of a BMW fairing, and that would be less profit for BMW. So if the rider wants a fairing, he must either go through the inspection process on an individual basis to buy a nonBMW fairing, or he can buy a BMW fairing and avoid the hassles.

A similar system applies to tires. For example, the registration certificate for a Yamaha XS11 says, right there in black and white, that the machine is approved for use on West German roadways with Bridgestone Mag Mopus tires. That means that it’s illegal to change to Continental or Metzeler or any other non-approved brand of tires. Whether or not the tires are as good or better than the Bridgestones doesn’t matter in the eyes of the government—they’re not approved, therefore they’re not allowed.

If a company wanted to sell its nonOEM handlebars or tires, for example, in West Germany, the certification process is again long, involved and expensive.

The handlebar manufacturer may have a bar which it sells in the United States as an unmarked, universal-fit part. In West Germany, that manufacturer would have to submit detailed technical design and manufacturing data concerning that bar to the government, state which motorcycles the bar would be sold for, and supply the government with one each of those motorcycles, with the bar fitted—and pay for the testing as well. For example, if XYZ manufacturing wanted to sell clubman bars for the KZ650, CB750 and XS750, then XYZ manufacturing would have to install the bars on a KZ650, a CB750 and an XS750> and bring those machines to the appropriate government office for inspection and testing. The government officials would review the technical data, ride the bike to determine whether or not handling at speed is affected, and compile a report with all the results. If the bars are approved—a process which typically takes two months—the report is then reproduced (usually reduced in size for convenience) and packaged with every set of bars sold. When a consumer buys and installs the bars, he takes the bike and the inspection/ certification report to a local government office, pays 10 DM (about $5.67) and goes away with a notation in his registration. which describes the non-standard bars by make and model number.

If Continental, for example, wanted its tires approved for the XS11, it would have to supply the government with an XS 11 fitted with Continental tires for testing. If approved, a copy of the government test results and approval would be given to everybody who bought Continental tires for an XS 11. At a government inspection station, an official would examine the copy of the test results, make sure that the tires fitted on the bike were the same ones certified, and have a notation made in the bike’s registration that Continental tires were allowed.

The agency charged with testing and certifying motorcycles and motorcycle components is the Technischer Überwachungs-Verein (T.U.V.), which has departments testing everything from atomic power plants to cranes to electrical wiring to heating systems to motor vehicles. All machinery and installations are covered by one department or the other, with offices located around the country. The agency is self-supporting, raising the money needed to operate through the charging of user fees.

The justification for the massive T.U.V. network is public safety, and the bureaucrats in charge take their reason for being very seriously. There are heavy consequences for making non-approved changes to your bike, and if they don’t catch you during the required once-everytwo-years comprehensive vehicle inspections, there’s still the chance of a policeman pulling you over and examining your bike’s registration to see whether or not any non-standard parts have been approved.

The penalties for non-compliance are severe, and non-approved high performance is persecuted in a county with no speed limits. That may be because the extremely-high West German insurance rates for motorcycles are tied to horsepower output. Liability insurance alone for the biggest bikes ran cost 1000-1200 DM per year, about $567-$680. But there are substantial rate breaks for machines with less than 50 horsepower and those with less than 27 horsepower. A non-approved, hopped-up engine is a threat to that rate system.

So if a rider modifies his bike’s engine and doesn’t get T.U.V. approval and a notation in his registration (which can mean higher insurance rates), then the insurance company doesn’t have to pay any claim arising out of an accident caused by that rider’s bike.

Wolfram F. Schilling, the man in charge of vehicle inspections and licensing for the Flanover area T.U.V., used this example of what could happen:

A rider installs a big bore kit in his bike, increasing displacement from 650 to 750cc. He is involved in a crash and says he was going a certain speed (say 115 mph). T.U.V. experts decide that the crash couldn’t have happened at the speed the rider said he was going, and that he had to have been going faster. But his model machine won’t exceed 115 in stock condition. The suspicious T.U.V. men order the bike’s engine torn down for inspection.

If the engine has been modified, the rider’s insurance company doesn’t have to pay, and may cancel his policy. The rider will also be subject to a stiff fine and his machine may be banned from road use until it is either restored to stock tune or it passes T.U.V. inspection and certification processes for modified machines.

Life is not even simple for the German motorcyclist who doesn’t install hop-up parts. Just getting a motorcycle license can be a harrowing experience. It isn’t as simple as going down to the local motor vehicle department and taking a test. Instead, a new rider must enroll in a driving school and pay for instruction. The typical 18-year-old (the minimum driving/riding age) needs 20 hours of instruction before he can pass the driving test for cars, and another four to five hours to pass the motorcycle test. Similar to the way some colleges in this country count “class hours” as being less than 60 min., an hour at a driving school is actually 45 min. But that 45 min. costs the would-be driver/rider 25 DM (around $14) at a relatively inexpensive school, and 36 DM (around $20) in a typical school. The $340-$510 worth of mandatory driving school doesn’t include the 30 mark ($17) license fee paid to the state nor the 14.50 DM ($8.22) tax on each lOOcc of engine displacement.

For the riding portion of the lessons, the school supplies a small motorcycle, an instructor and a car for the instructor. After preliminary practice around a large parking lot, the rider follows the instructor’s car out on public roads, while the instructor watches and evaluates the rider through an extra rear-view mirror.

(If you’re wondering how the driving instructor watches both where he’s going ahead of the car and what the rider’s doing behind the car, don’t feel alone. After riding along with the instructor down narrow German streets, I wondered the same thing. It may be a special trick taught by the T.U.V. during a week-long certification test given to all instructors, a test which covers theory, mechanics and actual driving.)

Once a rider gets a license, he has the every-two-years vehicle inspections to look forward to.

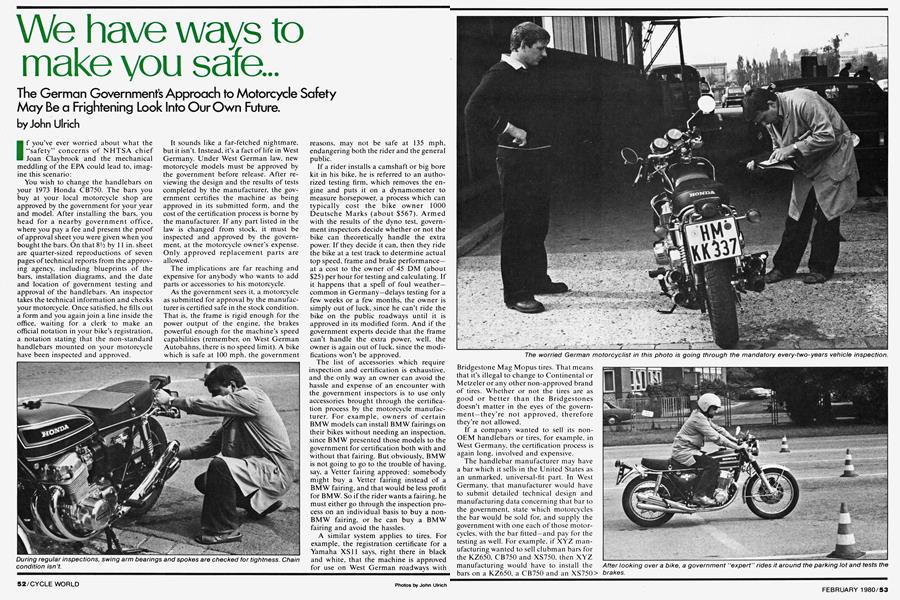

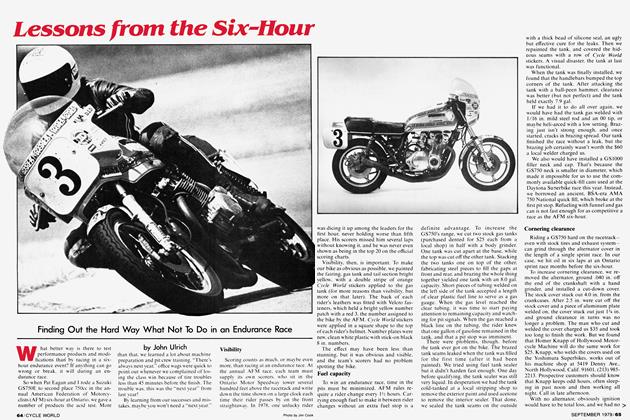

I watched an older CB750 being inspected at the Hanover T.U.V. office. The inspector checked the frame number, tire size, ply rating and speed rating against the registration (which, in this case, didn’t specify tire brand). Tread depth front and rear was less than the required minimum of 1mm, so the inspector checked the appropriate box on the inspection form to require the installation of new tires.

The inspector next checked to see that the steering head bearings, swing arm bearings, axles and spokes were tight. The front disc was checked for scoring, and the front brake lever checked for excessive travel. Headlight alignment, high/low beam, blinkers, brake light and horn were all tested. Then the inspector jumped on the bike, started it up and rode around the parking lot to test the brakes.

It may sound reasonable, but the inspection I saw cast doubts over the entire program. The “expert” inspector made brake test stops with all the authority of a two-year-old dragging his heels to halt a tricycle. The man looked to be afraid of the front brake and of the bike.

A good rider could stop harder and faster using only the little finger of his right hand on the brake lever.

As the inspector filled out his forms and chatted with the bike’s owner, I wondered when he was going to say something about the most unsafe thing on the bike—a rusted, un-lubricated, kinked, sagging drive chain with more than two inches of slack in the top run. The chain was ready to jump the sprockets and lock the rear wheel, or snap and break the engine cases (possibly lubing the rear wheel) at any moment—just the thing for excitement in the middle of a cobblestone curve.

Finally, the inspector shook the hand of the rider, handed him a copy of the inspection form, and started to walk away. “What about this drive chain,” I asked him. “It’s all rusted and loose.”

Without looking at the chain, the inspector glanced down his checklist and replied in German,

“It isn’t on the list of offical inspection items.” With that, the inspector walked into his office.

The motorcyclist started his Honda and rode off, drive chain clanking against the swing arm as he went. E9