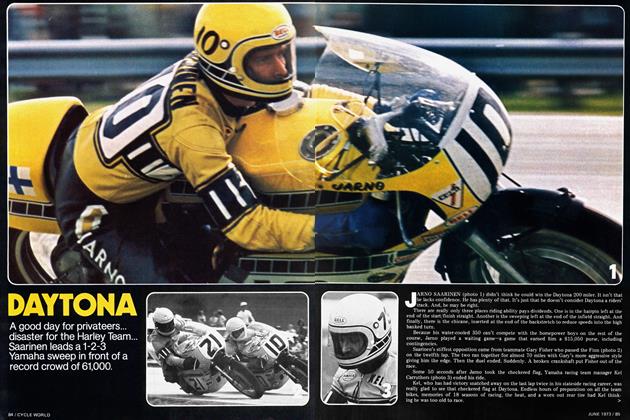

RIDING THE 250 RACERS

COMPETITION

Smaller Is Easier? Don't Believe It.

John Ulrich

I’m gonna ride the wheels off that thing and win. I’m adaptable. It’s ■ only a 250." Bruce Hammer, before riding a TZ250 Yamaha in an exhibition race at the Long Beach Formula One (car) Grand Prix. * * *

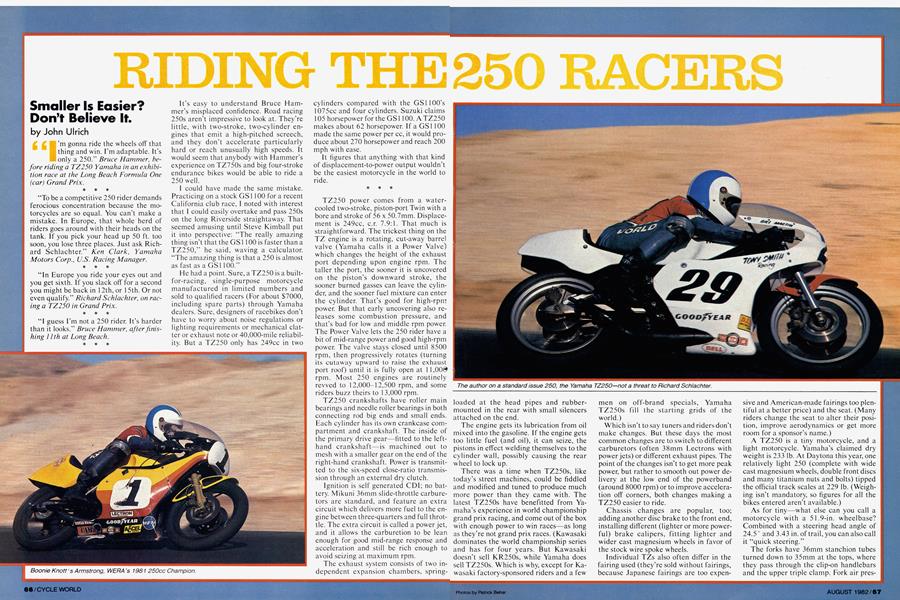

“To be a competitive 250 rider demands ferocious concentration because the motorcycles are so equal. You can't make a mistake. In Europe, that whole herd of riders goes around with their heads on the tank. If you pick your head up 50 ft. too soon, you lose three places. Just ask Richard Schlachter." Ken Clark, Yamaha Motors Corp., U.S. Racing Manager. * * *

“In Europe you ride your eyes out and you get sixth. If you slack off for a second you might be back in 12th, or 15th. Or not even qualify." Richard Schlachter, on racing a TZ250 in Grand Prix.

* * *

“I guess I'm not a 250 rider. It’s harder than it looks." Bruce Hammer, after finishing 11th at Long Beach.

* * *

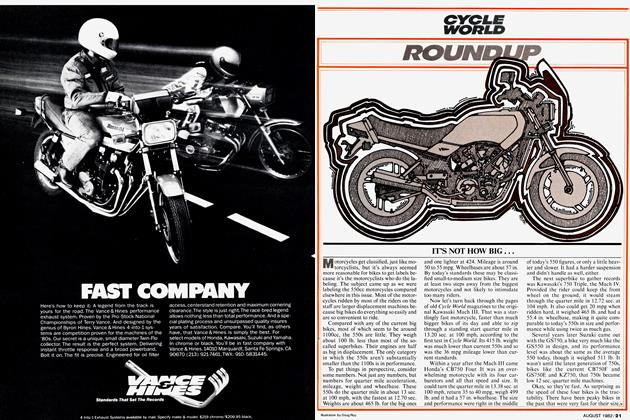

It's easy to understand Bruce Hammer’s misplaced confidence. Road racing 250s aren’t impressive to look at. They’re little, with two-stroke, two-cylinder engines that emit a high-pitched screech, and they don’t accelerate particularly hard or reach unusually high speeds. It would seem that anybody with Hammer’s experience on TZ750s and big four-stroke endurance bikes would be able to ride a 250 well.

I could have made the same mistake. Practicing on a stock GS 1100 for a recent California club race, I noted with interest that I could easily overtake and pass 250s on the long Riverside straightaway. That seemed amusing until Steve Kimball put it into perspective: “The really amazing thing isn’t that the GS 1100 is faster than a TZ250,” he said, waving a calculator. “The amazing thing is that a 250 is almost as fast as a GS1100."

He had a point. Sure, a TZ250 is a builtfor-racing, single-purpose motorcycle manufactured in limited numbers and sold to qualified racers (For about $7000, including spare parts) through Yamaha dealers. Sure, designers of racebikes don’t have to worry about noise regulations or lighting requirements or mechanical clatter or exhaust note or 40,000-mile reliability. But a TZ250 only has 249cc in two

cylinders compared with the GS1 100’s 1075cc and four cylinders. Suzuki claims 105 horsepower for the GS 1100. A TZ250 makes about 62 horsepower. If a GS1100 made the same power per cc, it would produce about 270 horsepower and reach 200 mph with ease.

It figures that anything with that kind of displacement-to-power output wouldn’t be the easiest motorcycle in the world to ride.

* * *

TZ250 power comes from a watercooled two-stroke, piston-port Twin with a bore and stroke of 56 x 50.7mm. Displacement is 249cc, c.r. 7.9:1. That much is straightforward. The trickest thing on the TZ engine is a rotating, cut-away barrel valve (Yamaha calls it a Power Valve) which changes the height of the exhaust port depending upon engine rpm. The taller the port, the sooner it is uncovered on the piston’s downward stroke, the sooner burned gasses can leave the cylinder, and the sooner fuel mixture can enter the cylinder. That’s good for high-rpm power. But that early uncovering also releases some combustion pressure, and that’s bad for low and middle rpm power. The Power Valve lets the 250 rider have a bit of mid-range power and good high-rpm power. The valve stays closed until 8500 rpm, then progressively rotates (turning its cutaway upward to raise the exhaust port roof) until it is fully open at 11,00$ rpm. Most 250 engines are routinely revved to 12,000-12,500 rpm, and some riders buzz theirs to 13,000 rpm.

TZ250 crankshafts have roller main bearings and needle roller bearings in both connecting rod big ends and small ends. Each cylinder has its own crankcase compartment and crankshaft. The inside of the primary drive gear—fitted to the lefthand crankshaft—is machined out to mesh with a smaller gear on the end of the right-hand crankshaft. Power is transmitted to the six-speed close-ratio transmission through an external dry clutch.

Ignition is self generated CD1; no battery. Mikuni 36mm slide-throttle carburetors are standard, and feature an extra circuit which delivers more fuel to the engine between three-quarters and full throttle. The extra circuit is called a power jet, and it allows the carburetion to be lean enough for good mid-range response and acceleration and still be rich enough to avoid seizing at maximum rpm.

The exhaust system consists of two independent expansion chambers, spring-

loaded at the head pipes and rubbermounted in the rear with small silencers attached on the end.

The engine gets its lubrication from oil mixed into the gasoline. If the engine gets too little fuel (and oil), it can seize, the pistons in effect welding themselves to the cylinder wall, possibly causing the rear wheel to lock up.

There was a time when TZ250s, like .today’s street machines, could be fiddled and modified and tuned to produce much more power than they came with. The latest TZ250s have benefitted from Yamaha’s experience in world championship grand prix racing, and come out of the box with enough power to win races—as long as they’re not grand prix races. (Kawasaki dominates the world championship series and has for four years. But Kawasaki doesn’t sell KR250s, while Yamaha does sell TZ250s. Which is why, except for Kawasaki factory-sponsored riders and a few

men on off-brand specials, Yamaha TZ250s fill the starting grids of the world.)

Which isn’t to say tuners and riders don’t make changes. But these days the most common changes are to switch to different carburetors (often 38mm Lectrons with power jets) or different exhaust pipes. The point of the changes isn’t to get more peak power, but rather to smooth out power delivery at the low end of the powerband (around 8000 rpm) or to improve acceleration off corners, both changes making a TZ250 easier to ride.

Chassis changes are popular, too; adding another disc brake to the front end, installing different (lighter or more powerful) brake calipers, fitting lighter and wider cast magnesium wheels in favor of the stock wire spoke wheels.

Individual TZs also often differ in the fairing used (they’re sold without fairings, because Japanese fairings are too expen-

sive and American-made fairings too píentiful at a better price) and the seat. (Many riders change the seat to alter their position, improve aerodynamics or get more room for a sponsor’s name.)

A TZ250 is a tiny motorcycle, and a light motorcycle. Yamaha’s claimed dry weight is 233 lb. At Daytona this year, one relatively light 250 (complete with wide cast magnesium wheels, double front discs and many titanium nuts and bolts) tipped the official track scales at 229 lb. (Weighing isn’t mandatory, so figures for all the bikes entered aren’t available.)

As for tiny—what else can you call a motorcycle with a 51.9-in. wheelbase? Combined with a steering head angle of 24.5 ° and 3.43 in. of trail, you can also call it “quick steering.”

The forks have 36mm stanchion tubes turned down to 35mm at the tops, where they pass through the clip-on handlebars and the upper triple clamp. Fork air pres-

sure isn’t adjustable, but spring preload can be set at one of three positions.

The rear end uses a triangulated, boxsection aluminum swing arm connected to a single rear shock. One end of the long shock is attached to the frame near the steering head, running back to the apex of the swing arm in a nearly horizontal plane. Adjustments include compression damping (36 positions), rebound damping (50 positions), nitrogen gas pressure, spring preload, and shock length (adjustable independent of spring pre-load, so ride height can be changed while the spring isn’t.)

Because 250s are small and light and have tiny engines, rider size affects performance. Jimmy Filice weighs 110 lb., David Emde 193 lb. Does it make it difference? Yamaha racing manager Ken Clark says “Being Jim Filice’s size would be an advantage. Given a 250’s power-toweight ratio, any excessive size on the part of-the rider really hampers the machinery.” Surprisingly, Emde has managed on occasion to make up the difference and get into the winner’s circle.

* * *

On face value, Hammer’s Long Beach ride seemed simple enough. His friend Gill Martin broke his collarbone in a minor crash at Talledega, and couldn’t ride at Long Beach. Martin’s bike was available and Hammer had ridden TZ250s earlier in his career, switching back and forth from a 250 to a 750 to a Superbike. But that was five or six years ago, before Hammer abandoned the 250 and Superbike to concentrate on his TZ750.

Maybe if he had asked Martin, Hammer would have been better prepared for Long Beach. Martin gave up campaigning both a TZ750 and a TZ250 after the 1981 season, to focus on his TZ250.

“If you’re going from a big bike, a 750, to a 250, the 250 feels like a toy,” said Martin, who weighs 140 lb., after Long Beach. “It feels like it won’t go fast enough. After a while, that feeling wears off, which is understandable. At some racetracks a 250 is almost as fast around the course as a 750.

“The biggest difference is that a 750 goes so fast. Most people are so far from the 750’s limit that if they go into a turn wrong, they can just grit their teeth, turn on the gas a little earlier and they’re back where they were. A 250 is less frightening. Riding one fast is more exacting because there isn't a surplus of horsepower and because more people can ride them at the limit. If you make a mistake, it takes longer to make it up in terms of distance and time, maybe one lap or two laps or five laps instead of one corner.”

By the time Martin said this, Hammer—who weighs 165 lb.—had already learned it on his own. “A 250 is a motorcycle that’s a racebike, but feels as if it’s reduced in scale. And it’s twitchy. It’s so easy to steer you have to be extra careful compared to a big bike. You’ve got to be sure of your line, because the steering is so fast it’s actually harder to change your line into a corner. You’ve got to ride it harder, and you’ve got to work at keeping it screaming, because if you don’t, it drops off the powerband. There’s none of this getting in too hot and just opening the throttle more to catch up. You must be precise in everything you do to ride a 250 fast.

“The strangest thing, though,” added Hammer, “is that it’s actually possible to

flip a 250 over frontwards with the front brakes, unlike a street bike that locks the front wheel or a Formula One bike that just does a front-wheel wheelie. Grab too much front brake and you can send the rear wheel over the handlebars.”

* * *

There are a few riders who can walk away from 250s for a period of time to race something else, then come back and be competitive. One of the few is Harry Klinzmann. In terms of a 250, Klinzmann is a giant at 6-foot-2 and 185 lb. Now 23, Klinzmann rides Superbikes, but he spent five years riding TZ250s almost exclusively, from the time he was 16 until he turned 21.

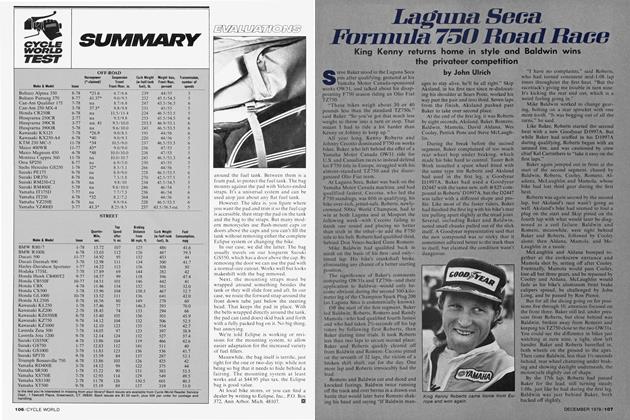

Klinzmann finished fourth at Long Beach, after being passed late in the race by Sam McDonald. Klinzmann rode McDonald’s spare bike: “After Sam passed me I didn't try too hard to pass him back, since I was riding his bike and he’s in the points race for the 250 Championship and I’m not.” The race was Klinzmann’s first time on a 250 in years.

The bike he rode was a 1982 TZ250J set up with 36mm Lectron carbs. The J models have more low and mid-range horsepower, compared to the 1981 TZ250H, thanks to changes in the exhaust system. The extra power in the middle

makes a J come off the corners harder. McDonald chose to ride his TZ250H with stock pipes and Lectron High Velocity carbs, which have a venturi starting at 40mm, closing to 35mm in the middle and opening back up to 38mm before the intake manifold. The differences in tuning saw Klinzmann doing wheelies and gaining distance on the 128-lb. McDonald accelerating off slow corners, while McDonald closed back up near the end of each straightaway. The pair seemed evenly matched through the corners.

“The bike seems smaller than I am,” said Klinzmann of his ride at Long Beach. “Like riding a toothpick. It steers really light, and I had to be careful pulling it leftright, try not to manhandle it like I do the superbike. I didn’t want to wrestle it so much the wheels came loose.”

Asked if he had any trouble adapting, Klinzmann said he didn’t. “It’s something you pick up and don’t forget. I rode 250s for five years, had a lot of fun and a lot of hard times. I’ll never forget it. But it really amazed me that as big as I am, the bike I rode kept doing wheelies.”

Talk to the mechanics who build and maintain TZ250 racebikes for front-running riders and they all agree that stock specifications are best.

“Don’t fix it,” is the first advice Emde’s tuner, Bob Endicott, offers. “My engine is absolutely stock. I’ve never touched my cylinders with a porting tool or even sandpaper.”

“The days of trick cylinder porting are gone,” says Tony Smith, who builds Martin’s bike. “All the fast 250s are stock motorcycles, put together correctly. Geared and jetted right.”

But beyond the stock-is-best stand, opinions vary widely. “The bike must be tuned right to the edge,” says Smith. “It must be jetted lean to the point where if you went any further, you’d seize it.”

“We found last year that if we run it a little bit richer it runs cooler and better,” says Endicott. “If it’s too rich it misses above 12,000 rpm, so we jet it a little leaner than that, just making it a little bit richer than (it would be to produce) a proper looking plug.

“We feel that the bike comes out of the corners a little harder when it’s a little rich,” says Endicott.

The disagreement goes further, into the oil mixed with the gasoline, and the ratio of oil to gasoline in that mix.

“We run 20:1 Yamalube R,” says Smith. “We’ve tried both Yamalube and Castrol R30. Castrol R works just as well but it’s messy. It doesn’t mix with gas as easily, and it gums up the rings quicker. Yamalube lubricates equally well, mixes more readily with gas, and burns with less carbon buildup. As for the mixture, articles I’ve read in SAE papers say that more

oil is better, but I don’t think there’s an advantage to running more oil. We’ve always used 20:1 and it seems to lubricate well enough. It’s also convenient—two bottles to a 5-gal. can of gas.”

“Our biggest trick is to run the oil mix at 15:1,” says Endicott. “I honestly believe it adds horsepower. I’ve read SAE papers on testing they’ve done and they say the more oil, the better. The fact that David (Emde) weighs 193 lb. and comes off the corners with guys who weigh 140— 150 lb. shows we have some power, and I think it comes from the extra oil. We run Castrol R30. We have to run a hotter spark plug, but it works good.”

Both Smith and Endicott run 38mm Lectron carburetors, but they disagree regarding front brakes. Smith has installed two discs on the front of Martin’s bike. Endicott runs the standard single disc because he feels the extra unsprung weight of two discs increases problems with front end chatter. It isn’t likely that the dispute will be decisively settled soon, since Martin and Emde often race each other on the

track, neither having a clear advantage anywhere.

* * *

Common as the Yamahas are, there is another brand making its mark in American 250cc road racing. It is Armstrong CCM, a British made racebike with a 247.3cc rotary-valve two-stroke Twin built by Rotax in Austria.

The Rotax Twin is a newer design than the Yamaha and represents a different school of engineering thought.

Like the world championship Kawasaki KR250, the Rotax is an inline Twin, with one cylinder in front of the other while the Yamaha has both side by side across the frame.

The inline allows thinner crankcases

and this lets Rotax put the rotary valves and carbs on one side, with a straighter shot at the crankcases than the crossframe engine could have. The six-speed transmission and dry clutch fit neatly behind the rear cylinder, the entire package being as compact as possible to keep the wheelbase as short as it can be made.

Rotary valves let the intake pulses be timed independently of the position of the piston. Rotary valves are one reason the current Yamaha and Suzuki 500cc GP bikes have their four cylinders in a square, like two Rotax or Kawasaki 250s side by side.

Rotax is an engine company, a subsidiary of Can-Am’s parent Bombardier. Rotax designs and makes and sells engines but not motorcycles, so the Rotax grand prix Twin appears in other limited-production 250 racers, like the Waddon ridden to fourth place at Daytona this year by Tony Head.

Armstrongs are brought into this country by TTFN Specialties (it stands for Ta Ta For Now), an independent distributing

company operated by Norma Bonelli with technical assistance from Boonie Knott. Riding an Armstrong, Knott won the 1981 WERA 250cc and 500CC GP Championships. (Before he got an Armstrong, Knott rode a TZ250 and finished fourth in the Formula Two class at the 1981 AMA National at Loudon, New Hampshire.) Seven Armstrongs have been sold in the U.S. as this is written, and Armstrongs have finished in the top 10 at AMA Nationals twice.

TTFN sells Armstrongs directly to racers, charging $6500 for a leftover 1981 model and $7500 for a 1982 model, including gearing, stand and parts book. A spares kit costs an extra $900.

The Armstrong’s Rotax engine has a

bore and stroke of 54 x 54mm. Lake the Yamaha, the Rotax engine is water-cooled and has CD ignition. The 1981 model came with 34mm Mikuni carburetors, while 1982 versions have 36mm Dell ’Ortos. The frame looks remarkably similar to a Yamaha frame and uses a single rear shock. The Armstrong shock, however, is made by DeCarbon and mounted vertically, connecting to the tubular chrome-moly swing arm through a rocking-arm linkage and a pair of struts. Forks are 36mm Marzocchis with magnesium sliders and adjustable rebound damping (13 positions). The rear shock has adjustable rebound damping (seven positions). Preload is adjusted w'ith a threaded collar. Wheelbase is longer than the Yamaha at 53.5 in. Rake is 26°, trail 3.0 in. The bike comes with twin cast-iron, drilled front discs with Brcmbo calipers and Dimag cast magnesium wheels.

According to Knott, the Armstrong

isn’t as sensitive to jetting as a Yamaha, running strong over a wider range of rich settings. The 1981 model also had a lower redline, 11,000 rpm.

The Armstrong factory recommends running Castrol R30 at a 20:1 premix ratio, but Knott uses Valvoline racing boat oil at 50:1. Because there are few Armstrongs being raced, there isn’t a wide range of tuning opinions to consider. For technical information, racers turn to Knott.

“The advantage the Armstrong has is that it accelerates off corners better than the Yamahas,” Knott says. “It’s funny, though. The first time I rode the Armstrong was at Gratten (Michigan). I didn’t think I was going as fast as I did on my Yamaha because the Armstrong sounded different . . . slower . . . throatier. But I lowered the lap record by two seconds.”

The biggest attraction to the Armstrong was, for Knott, the engineering and relia-

bility of the Rotax engine. Campaigning a TZ250G, Knott changed pistons every 300 mi., crankshafts every 500-600 mi. His 1981 Armstrong ran 1400 mi. before the rear crankshaft rod big-end bearing failed. Pistons lasted 400-500 mi., and the clutch went an entire season.

The comparison between an Armstrong and a Yamaha TZ250H or TZ250J isn’t as dramatic. In fact, Smith and Endicott both report nearly identical mileage out of their race engine. Yamaha durability and reliability took a quantum leap between the G and H models.

The Yamahas also come with a spares kit extensive enough that neither Smith nor Endicott had to buy any engine parts in 1981. The 1981 kit included two cylinders, two crankshafts, ten pistons, 30 rings, two cylinder heads, all gearing, ten steel clutch plates, ten fiber clutch plates, ten piston wrist pins and pin bearings, a complete set of Mikuni main jets and power jets, spare cables and enough gaskets and O-rings for five overhauls. The 1982 kit is essentially the same with added clutch plates, gaskets and O-rings.

* * *

I didn’t have all this information crowding my mind when I met Martin, Smith, Knott and Bonelli at Willow Springs one brisk fall morning for my introduction to life as a 250cc pilot. Jn fact, I knew next to nothing about 250s, any 250.

The Willow test session couldn’t fairly be called a comparison test. To test something, you’ve got to be able to ride it well.

That doesn’t apply here.

Next, Knott’s 1981 Armstrong came to Willow stock, as delivered, except for the fairing.

Martin’s 1981 TZ250H was fitted with 38mm Lectron carburetors, twin front discs with Spondon magnesium calipers, and TZ750-sized rims, a 2.5-18-in. (WM5) front and a 3.5-18-in. (WM7) rear. (Stock rim sizes are 2.15 WM3 in front and 2.5 WM5 in the rear).

Martin has raced extensively at Willow and as a result Smith knew how to set up Martin’s bike for the track. Knott, who serves as his own mechanic, had never seen the track before.

With that in mind, I rode the Yamaha first. Actually, I sat on it first, and was amazed that anybody could ride the thing. Martin is an inch shorter and 5 lb. lighter than I am, and the difference was exaggerated by Martin’s style of not moving around on the motorcycle. He likes the seat close to the gas tank and wedges himself into place.

My elbows rested on my knees as I got my first taste of TZ250 powerband. VF seemed like 7000 rpm would be enough to get the thing rolling out of the pits, but when I let the clutch out it promptly died. Slipping the clutch like mad, paddling and 9500 rpm got me moving, but as soon

as the clutch was all the way out the engine bogged below 8000, slowly picking up speed and starting to run again above 8500 rpm. Reasonable power came in at 10,500.

Abrupt. That's the word for a first lap on a 250. Touch the brakes and the action is abrupt. Make the slightest move with the bars or shift your weight and the change in direction is abrupt. Let the engine get off the powerband and the change is abrupt, from screaming to slow motion.

Coast through a corner without the power on and the front wheel hops and bounces in a rapid-fire chatter. The transition from power—once you've managed to find the power to brakes to cornering to power again is impossible to keep smooth. Even judging cornering speed is difficult, because nothing drags as an early warning that you're near going too far.

When the Yamaha is on the power between 10.500 and 1 2,000, which was as high as 1 chose to rev it the footpegs buzz and vibrate with unequalled intensity.

It gets better as I turn more laps, until I’m able to string together what seem like a few reasonable trips around the course. I come in, and the soles of my feet still buzz as I walk over to the Armstrong.

The Armstrong is a bigger motorcycle, and Knott likes to move around as he rides, so the seat is set back further. He weighs 160 lb., 15 lb. more than I do, and is a little taller. I fit on the bike better.

I also find it easier to ride, partly because I've gotten the general idea of what to do by riding the Yamaha, partly because the Rotax engine makes strong power from 9000 rpm. The Armstrong’s power delivery is better suited to torquing up the hill between Turn Three and Turn Four I had trouble keeping the Yamaha on the power through that section.

The Rotax engine is also smoother, producing much less vibration. It sounds bigger, more substantial, making a noise less like a screech and more like a growl. In the pits, I took the Armstrong’s small front calipers to indicate less-than-powerful brakes, but it stops as well as the Yamaha.

But it isn’t as stable, lacking the wide

wheels and tires of Martin's bike, so it twitches entering turns, and I have to be more careful and deliberate. The bike falls into curves quicker and with less steering input. Out in the hinterlands of sweeping, deceptive, bumpy, fast Turn Eight, the Armstrong wmbbles after hitting bumps— the suspension isn’t set up perfectly—and the bike feels less taut, less a whole.

Back into the pits, back out on the Yamaha. I gained some time by upshifting without the clutch—earlier shifts with the clutch were too slow, too deliberate, allowing engine revs to fall back and making the change lurehy. I learn to keep the revs up and to control chatter by rolling the gas on through corners. I keep the gas on longer through Turn Eight, and at the end of my second set of 10 laps on the Yamaha, Smith flashes a pit board that takes away feelings of accomplishment. The sign says “1.44.’’ One minute, 44 seconds. Slow for a stock GP/550. A full 1 3 seconds off the 250cc lap record for the track.

The same tricks I tried on the Yamaha worked on the Armstrong, too, with the identical lap time being the result.

Martin and Knott ride each other’s bike, and we compare notes. All agree that the wider rims and tires fitted to Martin’s Yamaha are a good idea, making the bike more stable. And that the Armstrong steers faster probably due to the rim and tire sizes again. And that the Rotax has more mid-range power, with less vibration.

Martin said that the Armstrong felt about 30 lb. heavier than the Yamaha. We didn’t have a scale on hand, but I agreed.

From there, who knows? Knott, the Armstrong rider and agent, believed the Armstrong to be easier to ride—compared stock for stock - than any TZ250. Martin and Smith, the team of Yamaha rider and tuner, concluded that, ultimately, the Armstrong and the Yamaha could be ridden at the same speed around any given track, with equivalent set-up. and that, for a beginner, the Armstrong was easier to ride.

But Smith doubted the Armstrong made as much peak power as the Yamaha, and to w in, he said, 250s must be ridden at peak power all the time. Knott countered

that the 1982 versions made more power, with larger carbs and different pipes, w ith stronger crankshaft main bearings to w ithstand more rpm, up to 12,000.

Only a few people will pay $7000$8000 for a racebike, Martin offered, and for those people to be persuaded to buy an Armstrong, the bike must be clearly superior, which, in his opinion, it isn't. People are used to dealing with Yamaha, he added. They're used to racing against other racers on Yamahas. They're comfortable with Yamahas.

But those same people could go faster on an Armstrong, Knott said, and they’d be dealing with a company that spoke their language (English) as its native tongue, a company with something to prove and a commitment to prove it. Armstrongs, he pointed out, were winning in England and at the Isle of Man, beating Yamahas.

Which is where we left it.

* * %

There’s more to racing 250s than meets the eye. They’re difficult to ride fast and the competition is intense and unending. To some, that might be a call to take up arms, roll out a Yamaha or an Armstrong or a Waddon or something else and take to the track.

For me, it’s been a nice visit, thanks.

But I don’t expect to w in a 250cc exhibition race at the 1983 Long Beach Grand Prix. gg