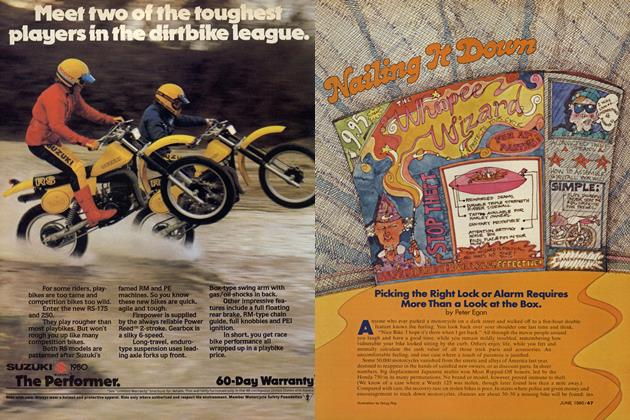

DAYTONA '80

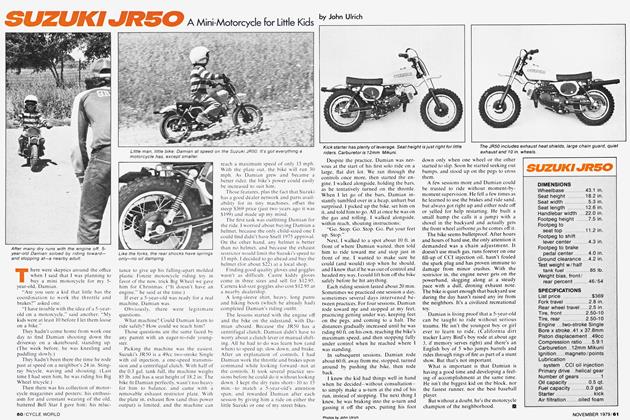

Yoshimura Stops Honda in Superbike Production

John Ulrich

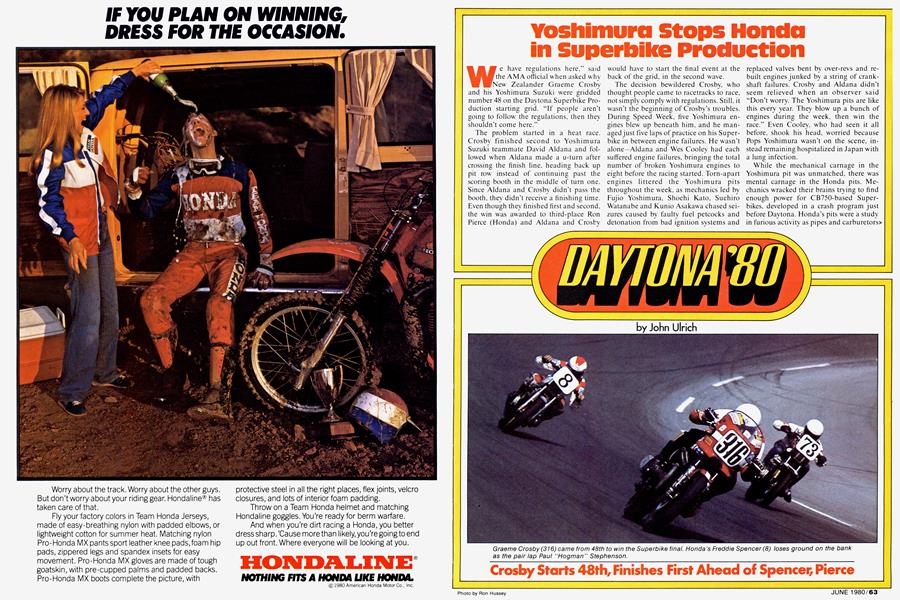

We have regulations here.” said the AMA official when asked why New Zealander Graeme Crosby and his Yoshimura Suzuki were gridded number 48 on the Daytona Superbike Production starting grid. “If people aren’t going to follow the regulations, then they shouldn’t come here.”

The problem started in a heat race. Crosby finished second to Yoshimura Suzuki teammate David Aldana and followed when Aldana made a u-turn after crossing the finish line, heading back up pit row instead of continuing past the scoring booth in the middle of turn one. Since Aldana and Crosby didn’t pass the booth, they didn’t receive a finishing time. Even though they finished first and second, the win was awarded to third-place Ron Pierce (Honda) and Aldana and Crosby

would have to start the final event at the back of the grid, in the second wave.

The decision bewildered Crosby, who thought people came to racetracks to race, not simply comply with regulations. Still, it wasn’t the beginning of Crosby’s troubles. During Speed Week, five Yoshimura engines blew' up beneath him, and he managed just five laps of practice on his Superbike in between engine failures. He wasn’t alone—Aldana and Wes Cooley had each suffered engine failures, bringing the total number of broken Yoshimura engines to eight before the racing started. Torn-apart engines littered the Yoshimura pits throughout the week, as mechanics led by Fujio Yoshimura, Shoehi Kato, Suehiro Watanabe and Kunio Asakaw'a chased seizures caused by faulty fuel petcocks and detonation from bad ignition systems and

replaced valves bent by over-revs and rebuilt engines junked by a string of crankshaft failures. Crosby and Aldana didn’t seem relieved when an observer said “Don’t worry. The Yoshimura pits are like this every year. They blow up a bunch of engines during the week, then win the race.” Even Cooley, who had seen it all before, shook his head, worried because Pops Yoshimura wasn’t on the scene, instead remaining hospitalized in Japan with a lung infection.

While the mechanical carnage in the Yoshimura pit was unmatched, there was mental carnage in the Honda pits. Mechanics wracked their brains trying to find enough power for CB750-based Superbikes, developed in a crash program just before Daytona. Honda’s pits were a study in furious activity as pipes and carburetors> were swapped, lap times checked, and more changes made. Working on the dyno before leaving for Daytona, Mike Velasco had already added 20 more horsepower to the original engine package sent to America by Honda RSC of Japan. That power came from a combination of El “Blue Magnum” carburetors, a cylinder head ported by Jerry Branch, and a new exhaust .system built bv Velasco using the RSC head pipes with a new collector and tail section. The Hondas were still down on power, but the team was forced to take a step backwards and install Keihin CR carburetors when Freddie Spencer and Ron Pierce complained that the four separately-operated (by a one-into-four cable) Els required too much effort at the twist grip. Tied together with a bell crank and using just one, lighter return spring, the CRs weren’t as hard to operate, but the bikes didn’t accelerate as hard off the corners. McLaughlin elected to stay with the Els.

Crosby Starts 48th, Finishes First Ahead of Spencer, Pierce

When early-week lap times didn’t meet expectations, the Honda men simply dropped a few bogus times for Spencer and Pierce into the pit rumor mill, then laughed silently as the information caused jaws to drop in amazement in rival camps. But the pace and pressure showed more on Team Honda than in other pits—on Tuesday of Speed Week, head mechanic Udo Geitl quit after an argument with team manager/rider Steve McLaughlin. The disagreement was smoothed over, and Geitl returned to his work, but the air remained tense.

At least the Hondas weren't blowing up as much as the faster Suzukis. Pierce had no engine failures, while McLaughlin had one. Spencer lost an engine to a spun main bearing in early practice, and his bike broke its cam chain in the last practice before the heat races. In the remaining two hours before Spencer’s heat, Velasco and David Langford replaced the broken engine with the good engine out of Ron Pierce’s RSI000 200-mile bike.

Viewed from ‘the outside, the doublesized Honda garage was incredible—parts stacked on shelves lining the walls, a dynamic wheel balancer, enough tires and wheels to seemingly shod the field, public relations men intercepting curious reporters.

Things were no better in the Moriwaki pits. In his first Daytona appearance, Mamoru Moriwaki had aimed for the most possible horsepower, having long heard that Daytona was a power track. Sure enough, the Moriwaki Zl-Rs ridden by Masaki Tokuno and Pat Eagan were plenty fast, but the powerband was basically on/off at 7000 rpm. Trying to get a drive off a corner was almost impossible, since the engine would go from bogging to blazing in a millisecond, lighting up the rear tire and sending the bike sideways. Eagan was miserable. “I’m riding the corners like an old lady,” he complained late one night. “It won't carbúrete at 6500, which is what you need for the corners. At least I’m riding a mean straightaway.”

On top of the engine troubles, the brakes weren’t working. Never having been to any track as demanding on brakes as Daytona, Moriwaki was unprepared. The stainless steel stock Kawasaki discs were warping after a few laps, the high-spots kicking the brake pads back on the straights. When the rider reached the corner and grabbed the brakes, the lever travel would be used up just moving the pads up to the disc, and it would take a pump or two to actually get brake action.

Changing to drilled 1979 Kawasaki discs and Ferodo 2447 pads helped, but the brakes were never too good. Unused to the exaggerated politeness of the Japanese, Eagan offended the mechanics by getting more and more upset after each practice session. Tokuno didn’t say much, but wasn't going any faster around the track than Eagan. That Tokuno went as fast amazed people who were told that the 25year-old Kawasaki factory test rider had raced only three times before Daytona. It didn’t come out until later that among the bikes Tokuno tested for the factory were the KR250, KR350 and KR500 road racers

Of all the high-profile, factory-affiliated team machines, the Kawasaki Motors Corp. KZ1000 Mk Ils prepared by Donnie Dove and Randy Hall faired the best during the week, working pretty much as they were supposed to in every practice. With 21-year-old California firebrand Eddie Lawson riding, one of Dove’s Kawasakis had the highest top speed recorded by the track speed trap during practice, 166.66 mph. Lawson’s teammate, Gregg Hansford clocked 161 mph without tucking in, making his first, superbike appearance. (“I don’t tuck in on streetbikes,” said GP star Hansford when somebody suggested it.) Nobody else made it past 160 according to AMA timing, although on gearing calculations the Yoshimura Suzukis were doing 170 mph. On the straightaway in practice, Lawson’s bike was as fast as the others, but not faster, calling into question the accuracy and consistency of the timing traps.

SUPERBIKE RESULTS Grame Crosby Suzuki Freddie Spencer Honda Ron Pierce Honda Masaki Tokuno Kawasaki Pat Eagan Kawasaki Dennis Smith Suzuki Harry Klinzmann Kawasaki Dwight Roy Suzuki Malcolm Tunstall Ducati James Adamo Ducati

Before the heat races, six riders reached lap times that could win the Superbike race: Spencer and Pierce on Hondas; Cooley, Aldana and Crosby on Yoshimura Suzukis; and Lawson on Kawasaki. All had turned 2:10 except Crosby, who reached 2:11 on the fifth of his five practice laps (remember, he spent a lot of time in the pits waiting for engines to be repaired.) Cooley turned the fastest lap in 1979, a 2:11.

The heats, then were no big surprise. Aldana and Crosby beating Pierce in one heat, Crosby saying afterwards that he thought he bent another valve on the start because the his bike wouldn’t pull as well as he thought it should; Pierce holding third in spite of frying the Honda’s clutch in the first race start he’d tried on his new bike. In the other heat, Cooley and Spencer went heads up for first place, back and forth, with Cooley leading into the chicane on the last lap and Spencer drafting to lead across the finish line. Lawson was third. His Kawasaki’s cylinder head was fitted with the regular Vs in. spark plugs and a second, 5/s in. plug for each cylinder, part of a trick new engine set up concocted by factory engineers. But the set-up was incomplete, and because the Kawasaki wrenches didn’t have the additional ignition parts needed to spark two plugs per cylinder, the 5/s in. plugs weren’t used or checked all week. On the grid for the heat, an auxiliary plug came loose on Lawson’s bike and leaked, but the mechanics didn’t have a smallsize plug wrench and couldn’t get one in time for the start. Lawson started with the plug finger tight and leaking, running in effect on three and a half cylinders.

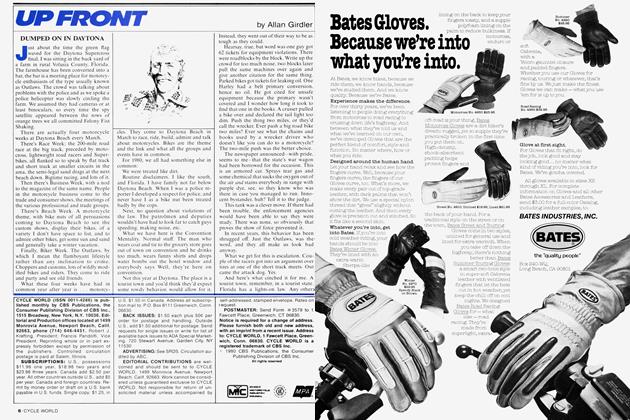

The race. Spencer led immediately with Cooley right behind. Pierce third, Lawson fourth, Eagan fifth, Hansford sixth. Spencer and Cooley pulled away slightly in a repeat of their heat-race battle, turning 2:10s and 2:11s. Pierce started out turning 2:12s in a solid third place but slowed to turn 2:14s and 2:15s when his bike’s rear brake started dragging. Lawson dropped out almost immediately, having fried the clutch at the start.

As Spencer and Cooley traded the lead, nicking into 2:09 lap times, Crosby and Aldana were charging up from the second wave. Aldana made it up to sixth place before he retired with a flat front tire, a problem he discovered when he couldn't make the turns and kept running off the track. Crosby had better luck, reaching eighth on the third lap (behind Cooley, Spencer, Pierce, Harry Klinzmann, Steve McLaughlin, Hansford and Eagan) and fourth a lap later. Crosby’s slicing through the field even startled Aldana (“He ran it in on some guys at the chicane pretty close, and I wasn't ready to hang it out that much,’’Aldana said later) and brought him down to 2:08 lap times in traffic, faster than the leaders turned with a clear track.

Meanwhile, Hansford and Eagan raced, both being passed by Honda’s Steve McLaughlin and Racecrafters’ Harry Klinzmann (Kawasaki). McLaughlin’s bike broke, and Hansford pitted because his bike’s gas cap kept vibrating open on the straights, allowing gas to spill out under braking.

By the time Cooley’s bike lost the crankshaft and quit on lap 11, Crosby was behind Spencer and closing fast, a fact Spencer first learned by glancing over his shoulder. When Cooley broke, Spencer backed it down to cruise at 2:14 and 2:15 lap times, and his pit crew didn’t signal him that Crosby was gaining. Suddenly Crosby was on him, then ahead of him, turning 2:09s and 2:08s. Spencer picked up Crosby’s pace instantly, but gradually fell back later in the race when his Honda started misfiring. (“My bike was close to Cooley’s in power,” Spencer would later say, “but Crosby’s bike was so fast it was ridiculous. He had 8-10 mph on me.”)

The first three places were set for the race, then, being Crosby, Spencer, and— almost a minute behind—Pierce. The remaining fight was for fourth between Eagan, Tokuno and Dennis Smith. Smith built and financed his Suzuki himself, using Yoshimura parts, and runs his own tuning business. Cycle Tune in Torrance, California. Klinzmann, who had been fourth after McLaughlin broke, started to run out of gas on the very lap he was to pit. Klinzmann made it into the pits by weaving to slosh the remaining gas to the petcock and riding slowlÿ.

Who led the group of Eagan-SmithTokuno wasn’t settled until the gas stops, when Tokuno’s fast stop gave him an advantage. Eagan lost 15 seconds in the pits when his bike wouldn’t restart after the dead-engine-when-refueling stop required bv the rules, but still beat Smith for fifth place.

Crosby took huge hits off the champagne bottle in victory circle after winning. “They shouldn’t have put me in the back of the grid like that,” he said. “It made me mad.”

Spencer, at 18 one of the most serious racers in history, was sorely disappointed in finishing second. “He was just down on power, that’s all,” said his father. “And they didn’t give him signals that Crosby was catching up. He didn’t want to complain to the pit crew after the race because he thought it would hurt their feelings.”

But despite finishing second, Spencer gained 16 points in the AMA Superbike Production championship race over Yoshimura’s Wes Cooley, the reigning champion. With Crosby headed for Europe and the grand prix for the year and Cooley down on points from not finishing, Freddie’s biggest competitor for the title may be teammate Ron Pierce. >

200-mile Formula One Expert Freddie Runs Away, Pons Finishes And the Four Strokes Prove Their Point

A 200 Yamaha this year, TZ750 just won as a Yamaha the Daytona won last year and the year before and the year before and . . .

More Yamahas followed, in second and third and fourth and fifth, if you believe the official results (which are still under protest as this is written), with David Aldana and the Yoshimura Suzuki finishing first four-stroke in sixth place, followed by Ron Pierce’s RS1000 Honda four-stroke in seventh.

But anybody who thinks that the results prove that 1025cc four-strokes can’t compete with the TZ750s didn’t see qualifying at Daytona, and didn’t watch the opening laps of the grueling race, a contest which perhaps can be best characterized as an endurance sprint. You’ve got to be fast, and you’ve got to last. “Run hard and go the distance” is a hard motto to follow.

Wes Cooley qualified a Yoshimura Suzuki on the front row of the starting grid at Daytona, fifth fastest at 2:07.349 (translated, that means he turned a lap in timed practice in 2 min. 7.349 sec.).

That’s four seconds faster than Cooley qualified his TZ750 for Daytona last year, and only 0.029 seconds slower than the 1980 qualifying time of Boet van Duimen, the third fastest qualifier. Richard Schlachter, the U.S. Road Racing Champion, qualified his Microion TZ750 fourth at 2:07.327, or 0.022 seconds faster than Cooley.

What that all means is that Cooley and his four-stroke were very competitive, even though Kenny Roberts qualified his Yamaha fastest at 2:02.397 and Freddie Spencer qualified second on his Howard Racing/Erv Kanemoto TZ, at 2:03.530.

Cooley may have been about five seconds slower a lap than Roberts, and almost four seconds a lap slower than Spencer, but he was competitive. For in road racing there are those who are competitive, and then there are those combinations of rider and machine which are more than competitive. combinations which can’t be challenged if the rider doesn't choose to be or if the machine doesn’t have some sort of mechanical problem.

In the recent past, Kenny Roberts stood alone in that second group as far as American racers went. When Roberts wanted to toy and play, other riders rode with him and appeared to be racing with him. But when Roberts got down to business, nobody could be close. The best example was Sears Point in 1979, where Roberts raced with Gene Romero and Skip Aksland, turning 1:47 lap times until he tired of the game and blitzed off a series of 1:45 lap times, leaving Romero and Aksland far behind.

Daytona 1980 marked the emergence of 18-year-old Freddie Spencer as the second member of the group of untouchables, a rider challengeable only by King Kenny Roberts himself. If slightly slower than Roberts, Freddie can be forgiven—he’s a fast learner and has a tendency to go faster in competition than he does in practice or qualifying.

To deal with the untouchables, the other racers point to the length of the race, hope or even assume that something will happen to the, too-fast-to-challenge few and then figure their strategy from there. In terms of everybody else, Cooley and his four-stroke were the match of the TZ750s.

And only a string of blown-up engines and missed practice time prevented Cooley’s teammates, Graeme Crosby and David Aldana. from serving notice of their ability to compete before the race started.

The competitiveness of the four-strokes surprised some, who figured that the extra weight of engines based on street bikes would severely handicap the bigger machines, compared to the Yamahas.

“The weight difference doesn't seem to matter much,” said Cooley before the race, after qualifying. “The Yoshimuras have gotten the weight of my bike down to within 10 lb. of a standard TZ750. Sure, it’s more than 10 lb. heavier than a really trick, light Yamaha like Kenny’s or Freddies, but compared to the bikes everybody else has, it’s not bad. The hardest thing is when you’re braking, because the engine wants to slow down faster than the w heels. If you panic and aren’t ready for it and let the clutch out too quickly there’s lots of wheel chatter. But the bike seems to out-accelerate the Yamahas, and in top speed it’s pretty close to most of them.”

On pit row between practice sessions earlier in Speed Week, Eddie Lawson, riding a Moriwaki KZlOOO-based Kawasaki. talked to TZ750 pilot Ted Boody.

“It’s hard to get back and forth because it’s top-heavy,” said Lawson, “it’s hard to muscle around and hard to get stopped because it’s so heavy. You can feel all the weight transfer on the brakes. It doesn't seem that fast either.”

“What do you mean?” asked Boody. “You pulled me really bad coming out the chicane. That thing is fast.”

“You must have a slow 750,” said Lawson. “And my bike gets into a wobble coming onto the bank, accelerating. I didn’t see any of the 750s do that. I guess it accelerates pretty good, as good as a 750 but I don’t know about top speed. Roberts went past me like. . .”

Lawson's job was complicated by brake problems. Bike builder Mamoru Moriwaki has used stock KZ1000 stainless steel discs with Lockheed calipers with success at every other racetrack he’s competed at. But at Daytona for the first time, under the stress of hauling down from close to 170 mph for Turn One, and again for the back straight chicane, the discs were warping. Once warped, the discs would knock the brake pads back on the long straights, and it would take two or more pumps of the brake lever to first move the pads up to the discs, then get brake action. Lawson almost crashed in Turn Two in practice w hen the brake lever came into the grip, and returned to the pits shaken. Still using those brakes, Lawson qualified 13th with a 2:10.603. as fast as Pierce qualified the Yamaha Motor Canada YZR750—which he rode to finish second—in 1979.

For the race, Lawson’s Superbike sponsors jumped in to help. Gary Mathers and Randy Hall of Kawasaki Motors Corp. allowed the Moriwaki mechanics to take the complete front ends off the Kawasaki superbikes of Lawson and Gregg Hansford and install them on the 200-mile machines of Lawson and Japanese rider Masaki Tokuno. Those front ends carried KR750 brakes, possible the most effective superbike brakes seen at Daytona. With the better brakes, Lawson would later turn 2:09s in the race.

Ron Pierce had a different problem with his RS1000 Honda prepared by Honda RSC. “My bike handles real light.” said Pierce right before the start of the race. “It feels lighter than it is, and steers easily and quickly. But the thing is that the suspension’s not dialed in. We just didn’t have time to dial in the suspension, because we were working so hard on the Superbikes earlier in the week. The rear end is chattering real-bad. and you can’t flick it into the turns because of that. You have to be very slow and deliberate, sort of roll it into the turns, because if you make any sudden moves you're gonna fall down. It’s just a matter of minor adjustment, but we haven't had time to sort it out. Plus, because Freddie blew' up his good superbike engine just before the superbike heats, we had to take the fast engine out of the FI bike and put it in his superbike. They haven't had time to rebuild that engine, so I’m starting the race with a slower practice engine. We’re just gonna do the best we can and go for the finish.”

He didn’t say so at the time, but a mechanic confided later that Pierce considered riding the better-handling Honda CB750F-based Superbike in the 200-mile race. The disadvantage of the Superbike’s smaller gas tank and lack of proper quickfill refueling fittings persuaded Pierce to ride the RS1000.

Worried that the engine might not last 200 miles since the two surviving Superbike engines showed signs of rapidly-approaching cam chain failure after just 100 miles of racing. Pierce’s mechanic, Jyo Bito (who wrenched on the Yoshimura Suzukis Pierce raced in 1979, and who followed Pierce to Honda for 1980) fabricated and installed additional cam chain guides and tensioner parts in Pierce’s bike.

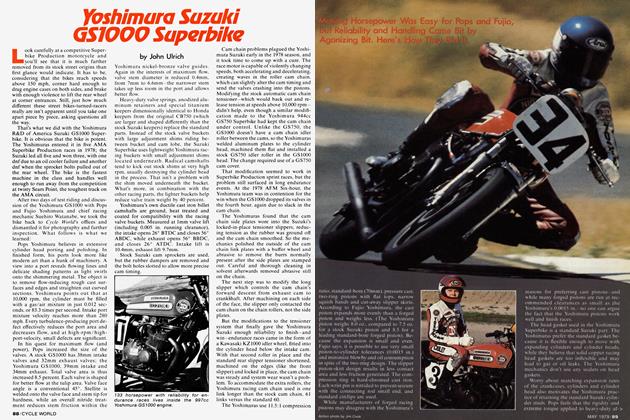

All the four strokes were plagued by vibration. In practice, Lawson’s Moriwaki Kawasaki shook so badly that it put his hands to sleep and numbed his arms to the> shoulders. Pierce's Honda vibrated badlv enough to crack the tachometer glass. Some of the Yoshimura Suzukis were relatively smooth with special full-circle counterweight crankshafts, but the cranks were failing at an alarming rate throughout the week. Other Yoshimura bikes with modified standard crankshafts shook more, but the pork-chop counterweight cranks didn’t come apart.

When Aldana’s previously-smooth FI engine started vibrating in the last practice before the 200 mile race started. Yoshimura mechanics attacked two engines at once, taking the crankshaft from a superbike engine and installing it in Aldana’s FI machine, and changing the transmission as well (the special cranks had a different primary gear ratio than the modified standard cranks used last year and in some of this year’s six Yoshimura Suzukis built for Daytona).

Some of the Yoshimura mechanics worked feverishly, others somewhat lackadaisically. as Aldana nervously paced. When the first wave of the race w as (lagged off. Fujio Yoshimura and two mechanics were still trying to push start Aldana’s bike. (When I got on it.” Aldana would say after the race, “the gas tank straps were missing. I had to hold the tank bn with my knees. The steering damper was hanging down. 1 had to put one spark plug lead on by myself, as I came onto the banking. They just barely got it together, and it really wasn’t all the way together.”)

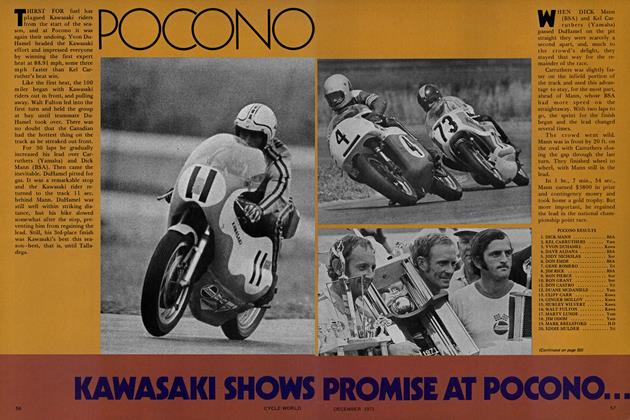

While Aldana almost missed the start — and in fact got going well after the second wave had left-Wes Cooley got the holeshot and led everybody into Turn One, including Dale Singleton, last year’s winner. Singleton, confident that the fourstrokes couldn’t do the job, had bet Cooley that Cooley couldn’t beat him to the first turn—so had lost money before the second turn.

Schlachter was second into the first turn, followed by Van Duimen, Crosby on another Yoshimura four-stroke, Singleton, Patrick Pons, Roberts, Spencer and Kevin Stafford.

Schlachter fried his bike’s clutch off' the start, but passed Cooley before the second turn to lead until the chicane, where he pulled off’. That left Cooley and Crosby and the big four-strokes in front, and Crosby led across the finish line of lap one. When Crosbv overshot Turn One and ran oft' the track with the first signs of a brake problem that would later take him out of the race. Cooley was again up front. By the second turn of the second lap. Pons and Spencer were past, with Cooley third.

Roberts pitted that lap, a victim of sticking carburetors, a problem he said later probably was caused by dust and grit sw irled up by a gust of wind just before the start. With the pole (inside of the first row of the starting grid) position, Roberts was right next to the pit wall, where windblown dust and dirt accumulated during the week. When the wind gusted. part of the cloud of foreign matter found its way into Roberts’ carbs, and one wouldn’t close after the start, kinking a throttle cable and making continuing pointless. Roberts finished the first few lap slipping the clutch in turns when the throttles wouldn't close. but knew the clutch wouldn’t last long, and that he couldn’t race that way.

Retirements came fast and furious, even in the opening laps. Mike Cone of Texas, always a front-running privateer on his self-sponsored, self-tuned Yamaha, suffered the same problem Roberts did, and pulled in when he figured that continuing with his barely-controllable motorcycle would only endanger other riders. Masaki Tokuno, the Kawasaki factory test rider brought to Daytona to race a Moriwaki Kawasaki, got sucked in by the massive first-lap draft on the back straightaway and entered the chicane way too fast—and, predictably, crashed.

Fast Freddie Spencer made his move on the second lap, taking the lead from Pons and taking off. cutting laps several seconds faster than anybody else. It was Freddie alone out front, pacing himself, running 2:02s, 2:03s 2:04s and 2:05s while the rest of the front runners ran 2:07s. Watching Freddie come through the infield Turn Four showed why he was in front and everyone else slowly slipping behind. The field took Turn Four on the inside, close to the apex. Freddie came in visibly faster, stuck out the rear end and barrelled around the outside, on the gas. During the entire race, spectators would see only one other rider come into the turn so fast—and that nameless mid-packer would run off the track and barely avoid crashing.

“Freddie went out and set a blistering pace.” Dale Singleton, last year's winner, would say later. “Nobody in the world could have caught him. I think Freddie would have given Kenny a run for his money if those two guys had been in the race the whole way.”

continued on page 118

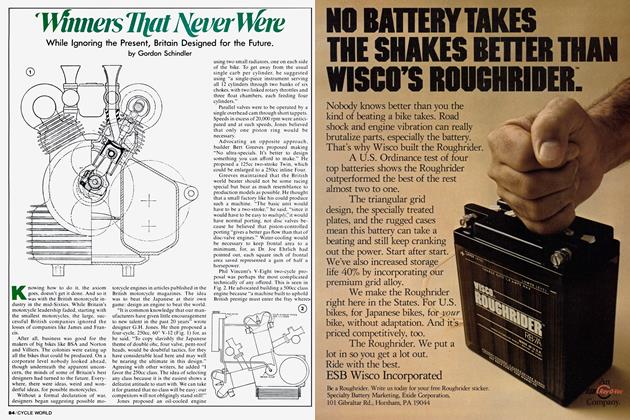

Aldana’s Protest

Racing is supposed to be simple, i.e. the first guv who gets to the finish line wins. Deciding second place, at least in the case of Yoshimura rider Dave Aldana. isn't so simple.

During the first nine laps leader Freddie Spencer lapped Aldana on the 8th lap. Then on the 10th lap the red (lag came out with the rain and forward progress ceased. There being no wav of spacing out the riders on the regrid exactly as they finished the first nine laps (or in the case of the lapped riders, the first eight laps), riders were allowed to close up. so to speak, the distance between themselves and the riders they were following, except that they couldn't unlap themselves.

So Pons and Singleton and the other riders following Spencer but who hadn't been lapped by Spencer ended up immediately behind Spencer in the order of their finish after nine laps. But what about Aldana? Having been lapped bv Spencer.

Aldana had only finished eight laps when the red flag came out and, according to the officials, the only distance he could make up was the distance from the first row to his spot on the grid in 47th position.

Restarting in 47th position. Aldana worked his way through the pack during the race, passing all of the leaders but Pons. Spencer wasn't in the race at the end and Aldana had never been lapped by Pons or Singleton or any of the other racers left, so he claimed second place.

Where Aldana got “lapped” by Pons and Singleton and the other top five finishers was during the restart calculations, not on the track during the race, so Aldana figures he came in second, finishing behind Pons and having not been lapped by anyone except Spencer who didn’t finish the race.

His protest was denied and he is awaiting a decision on his appeal of the denial.— Steve Kimball

continued from page 68

Gene Romero moved his Busch Beer special tuned by Don Vesco from fifth to second by the fifth lap. a lap which also found Skip Aksland charging past Cooley and Van Duimen into fourth. Now it was Freddie in front, and a nose-to-tail battle between Romero. Pons. Aksland, Van Duimen and Cooley for the next positions, then a gap. and everybody else coming along far behind.

Crosby was mired back in 12th. confused and vexed that he couldn’t seem to stay on the racetrack. At anv given turn, Crosby was likely to be seen sailing off onto the grass, turning around, and charging off on one lap. only to make the turn the next lap and run off' again on the following lap in the same place.

Pierce and Lawson ran back and forth on their four-strokes back in 15th and 16th; Singleton was in 11th after getting sideways in one turn and losing concentration.

By the end of the sixth lap Cooley had parked, covered with oil from a blown cam cover gasket; and David Enide had stopped his Hap Jones TZ750. fouled again in a tale of frustrating privateer luck.

Then it rained. A fast-moving squall pelted the track, sending Kevin Stafford down in Turn Four before he could react, with Pierce diving inside the falling Yamaha and Lawson running off' into the soft dirt to avoid the moving obstacle. The race was red flagged. Spencer led by 20 seconds, with Romero, Aksland. Van Duimen and Pons behind.

The two-and-a-half hour break between red flag, the passing of the squall and the drying of the track enough to allow continued racing on slicks was a godsend for many riders. Cooley’s cam cover gasket was repaired, although Cooley wouldn't be as enthusiastic about charging in the restart. since he wars four laps down. Pierce's mechanics fiddled with suspension, while Aksland’s replaced an ignition system Aksland thought was responsible for a lack of “pull” at high rpm. Crosby, still befuddled by his inconsistency and inability to stop running off' the track, didn't ask the Yoshimura mechanics to do anything to his bike—he thought the trouble lay somehow in his riding.

“These rains are my big break.” said Singleton. “This is what we need. It couldn’t be any better. We were a bit disorganized this morning and I didn't get out to buff'in the tires in practice, so I went out with fresh rubber and we had the motorjetted way too rich. Now the tires are buffed in and we just changed jets. It's a psychological thing, because if you have to go out there in the race and you’ve got tires to break in, you have to be real careful and pace yourself and actually hold yourself back. But when they drop the flag and you know you have everything set then you go as soon as the tires are hot and it’s a lot easier to do.”

The restart wasn’t much of a surprise, even after the changes some riders made to their machines. Pons led briefly, then Spencer flew by and stretched it out, pulling 10 seconds ahead in five laps. Aksland and Romero traded second place until Romero went wide in Turn One and crashed. That left Freddie way out front. Pons second and Aksland and Van Duimen racing for third, 22 seconds behind Pons. John Long was fifth. Crosby sixth. Marc Lontan of Lranee seventh, Singleton eighth. Aldana ninth on the racetrack.

Back in 16th, the rear brake stay arm on Pierce’s Honda broke, dragging the ground and disabling his rear brake. Lawson passed.

Suddenly, more retirements. Lawson crashed in Turn One while following Pierce again, going in a little wide and meeting the same fate jn the same place as had Romero and John Bettencourt. Crosby pitted, finally having figured out that it was his bike, not him, misfunctioning—the left outside front brake pad had worn completely out and then some, the pad backing falling out and the aluminum caliper piston rubbing against the disc. Brake action was inconsistent—often with the lever going straight to the grip—and the piston deposited an uneven layer of aluminum on the disc surface.

And then Spencer’s bike broke, the crankshaft failing on the back straight of the 39th lap. Spencer had led 38 of those laps across the finish line, and held a oneminute advantage over Pons. The look on his face as he parked near the chicane said it all for Fast Freddie. The race was his, victory was certain. Too bad metal can’t comprehend . . .

Blackflagged, Pierce quickly pitted to have the loose brake arm torn off his Honda, rejoining the race in seconds.

Singleton, on the move and simultaneously dicing with Aldana, passed Aksland, whose shoulder was still weak from corrective surgery following a 1979 dirt track injury. Van Duimen got Aksland soon after. Aksland unable in closing laps to hold his weight under normal braking.

On the track, Aldana passed and now led all but Pons, a fact which would set up a protest and challenge to the official results. Those results show Pons winning— uncontested—with Singleton second. Van Duimen third. Aksland fourth, Fontan fifth. Aldana sixth. Pierce seventh.

The question of whether or not Aldana should have been scored second or sixth or something else remains.

The question of whether or not 1025cc four strokes can compete and make for better racing has been answered. 13