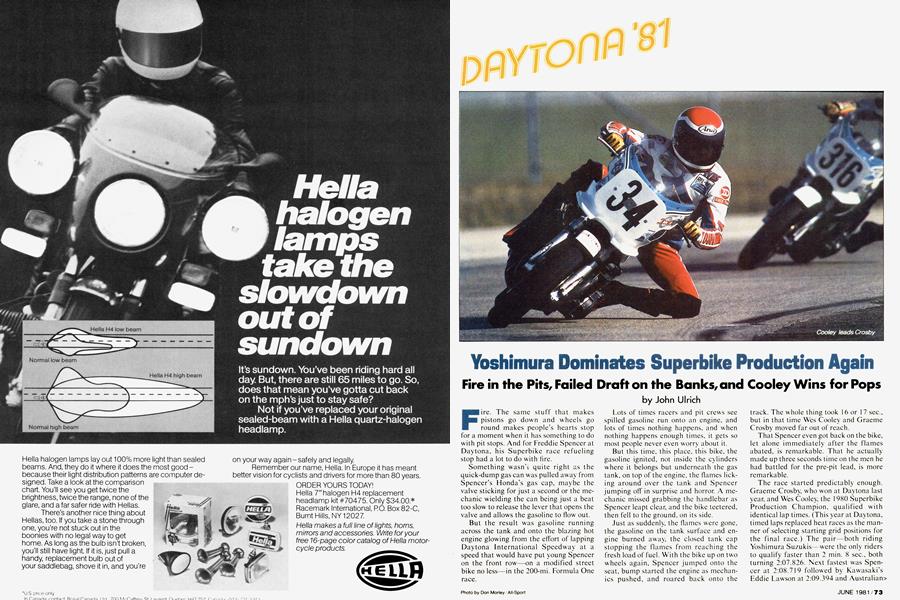

Yoshimura Dominates Superbike Production Again

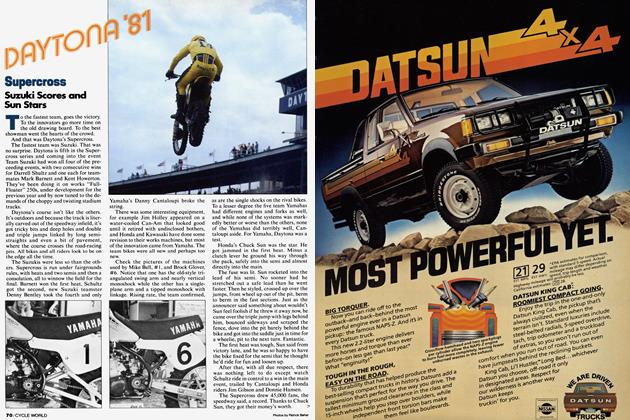

DAYTONA'81

Fire in the Pits, Failed Draft on the Banks, and Cooley Wins for Pops

John Ulrich

Fire. The same stuff that makes pistons go down and wheels go round makes people's hearts stop for a moment when it has something to do with pit stops. And for Freddie Spencer at Daytona, his Superbike race refueling stop had a lot to do with fire.

Something wasn’t quite right as the quick-dump gas can was pulled away from Spencer’s Honda’s gas cap, maybe the valve sticking for just a second or the mechanic wielding the can being just a beat too slow to release the lever that opens the valve and allows the gasoline to flow out.

But the result was gasoline running across the tank and onto the blazing hot engine glowing from the effort of lapping Daytona International Speedway at a speed that would have put young Spencer on the front row—on a modified street bike no less—in the 200-mi. Formula One race.

Lots of times racers and pit crews see spilled gasoline run onto an engine, and lots of times nothing happens, and when nothing happens enough times, it gets so most people never even worry about it.

But this time, this place, this bike, the gasoline ignited, not inside the cylinders where it belongs but underneath the gas tank, on top of the engine, the flames licking around over the tank and Spencer jumping off in surprise and horror. A mechanic missed grabbing the handlebar as Spencer leapt clear, and the bike teetered, then fell to the ground, on its side.

Just as suddenly, the flames were gone, the gasoline on the tank surface and engine burned away, the closed tank cap stopping the flames from reaching the fresh load of fuel. With the bike up on two wheels again, Spencer jumped onto the seat, bump started the engine as mechanics pushed, and roared back onto the track. The whole thing took 16 or 17 sec., but in that time Wes Cooley and Graeme Crosby moved far out of reach.

That Spencer even got back on the bike, let alone immediately after the flames abated, is remarkable. That he actually made up three seconds time on the men he had battled for the pre-pit lead, is more remarkable.

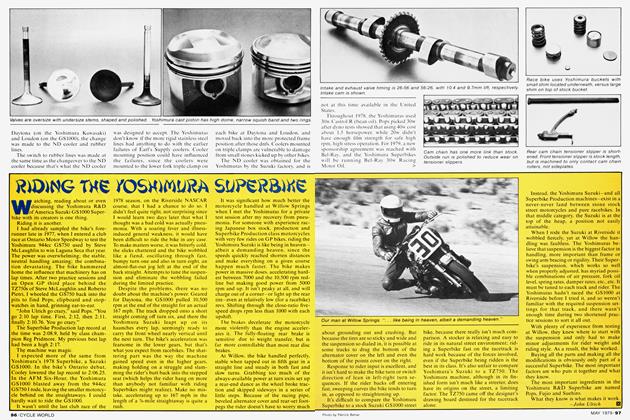

The race started predictably enough. Graeme Crosby, who won at Daytona last year, and Wes Cooley, the 1 980 Superbike Production Champion, qualified with identical lap times. (This year at Daytona, timed laps replaced heat races as the manner of selecting starting grid positions for the final race.) The pair—both riding Yoshimura Suzukis—were the only riders to qualify faster than 2 min. 8 sec., both turning 2:07.826. Next fastest was Spencer at 2:08.719 followed by Kawasaki’s Eddie Lawson at 2:09.394 and Australian> Wayne Gardner on a Moriwaki Kawasaki at 2: ! 1.228.

Cooley led the start and the first lap, chased by Crosby and Spencer, Lawson holding a close fourth through the infield.

It was hard to tell who had an advantage on the banking, if indeed any of the three did. After the race, all would say that the two Suzukis and single Honda were even in power. But in the infield turns, it was plain as the race progressed that the Suzukis accelerated more evenly and more smoothly out of the slower turns, while Freddie Spencer’s Flonda bogged, then came on the power violently, lighting up the rear tire momentarily, the rear end stepping out and catching, with the rear bouncing up and down and the bars wobbling before it all straightened out and Spencer accelerated toward the next turn. The problem could have been as much related to shock absorbers overheating as it was to power delivery, but it was clear that the Suzukis did work better off the corners.

One lap a cheer rose in the crowd, when Freddie Spencer passed Crosby to take the lead in Turn Four. The same lap Crosby and Cooley drafted past Spencer and put him back into third place before the back-straight chicane. Cooley led across the finish two laps, Crosby the next two, Cooley again one lap, Crosby the next

and back and forth and back and forth and back and forth. All the time Spencer was right there, always close, always within reach and sometimes in second place instead of third, but never leading across the finish line, not this early in the race. He was content to sit and wait, he would say later, trying to conserve his bike’s tires and confident that he could “run it up,” or go faster, near the end, when it counted.

Run it up!

When that first part of the race saw Cooley, Crosby, and Freddie Spencer all lapping at 2:06, as fast as second-fastestFormula-One-qualifier Dale Singleton’s time, faster than everybody in Formula qualifying except Singleton and Kenny Roberts.

Crosby did it twice before the pit stops started, a 2:06.17 and a 2:06.81. Cooley did it once before his pit, a 2:06.41. Freddie also did it once, at 2:06.80. (Most other laps turned by the trio were 2:07, a few at 2:08).

But Cooley had two more after his pit stop, a 2:06.95 and a 2:06.98; and Crosby reached a 2:06.89 after refueling. As hard as he tried after his bike and its throttle cables were singed by fire in the pits, Freddie didn’t turn any more 2:06 laps, and even if he had, he couldn’t have caught up anyway.

Crosby and Cooley snicked into the pits for gas running nose-to-tail, in at the same time, and left quickly with Cooley in front, still nose-to-tail. When they pitted on the 13th lap, Lawson inherited and held the lead, securely. Lap after lap, Lawson rode around, out front, spectators wondering when he would stop for fuel. Obviously, Kawasaki’s plan was for a late, late pit, and, judging by the size of their quick-fill can, adding just enough fuel to finish.

No matter. Never mind the strategy. Cooley and Crosby caught and passed Lawson, and Lawson’s KZ 1000J-based Superbike sprung a leak at the o-ring sealing the cylinder cam chain tower to the cylinder head. Oil drenched Lawson and the bike and ended his ride.

Honda’s Mike Spencer had refueling problems of his own. His bike ran short of gas and barely limped into the pits, and Mike left the pits with gasoline running across the tank. When he tucked in on the first straight section following the pits, wind turbulence whipped the gasoline into his face and onto his shield. He made it through part of the course, barely able to see, but finally ran off in one turn. All that was left of the race was who would win.

“I started slowing down at the end,” said Crosby, “and the lead changed. Wes led from there and I was going to draft him on the last straight and win.”

“Crosby tried to do what I wanted to do on the last lap,” said Cooley. “A couple of laps earlier 1 got behind him and was able to draft him and pass him on the straight, leading across the finish. He was leading with two laps to go and slowed down, but there was no way 1 was going to slow down, too, because sometimes that doesn’t work. I got by one (lapped) guy he didn’t get by in Turn Five, and tried to make the

chicane as smoothly as I could on the last lap.”

“I could have passed Wes before the chicane on the last lap,” said Crosby, “but that would have put me in the front then. So I waited and came out of the chicane behind him, and we both got sideways, and his bike recovered quicker. My bike just did not get into his slipstream until it was too late. I just blew it.”

Which meant that Cooley, despite leading a close race on the last lap and thus being a prime candidate for being drafted and beaten on the last lap, won.

“I used 1 1,500 (instead of the normal 10,500 rpm) and had the bike buzzin’ on the last two laps,” said Cooley. “I was going to win or blow, nothing in between!”

“I am very, very, very happy,” said Pops Yoshimura, who supervised the Yoshimura team’s unusually-smooth and trouble-free race week.

The crowd cheered. Pops signed autographs and grinned. Cooley floated on air. Crosby kept a stiff upper lip, and Freddie did a good job of hiding his disappointment.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

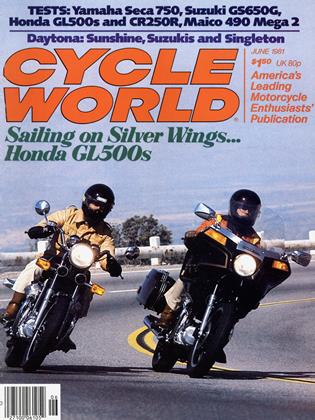

Up FrontInnocence Vanquished, Fatherhood Victorious

June 1981 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1981 -

Department

DepartmentRoundup

June 1981 -

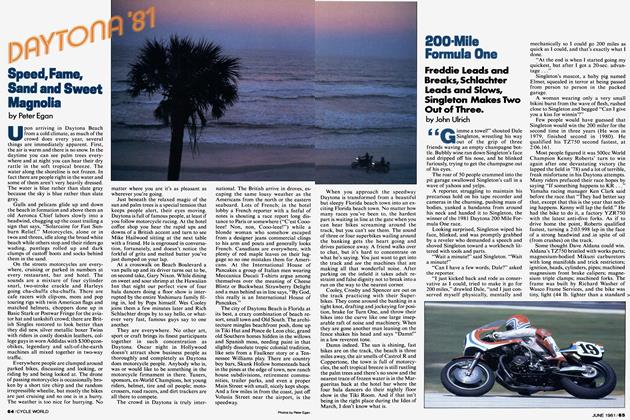

Competition

CompetitionDaytona'81 Speed, Fame, Sand And Sweet Magnolia

June 1981 By Peter Egan -

Competition

Competition200-Mile Formula One

June 1981 By John Ulrich -

Daytona'81

Daytona'81The Battle of the Twins

June 1981 By Peter Egan