Bell 100 Superbike Race

DAYTONA '82

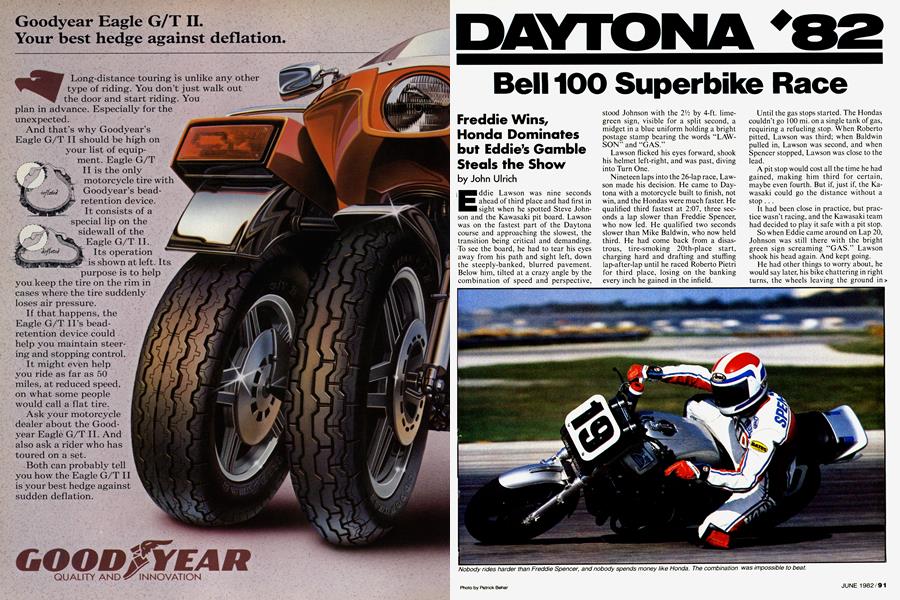

Freddie Wins, Honda Dominates but Eddie’s Gamble Steals the Show

John Ulrich

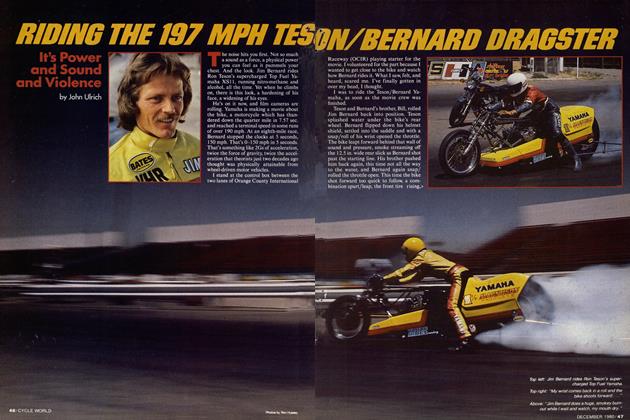

Eddie Lawson was nine seconds ahead of third place and had first in sight when he spotted Steve Johnson and the Kawasaki pit board. Lawson was on the fastest part of the Daytona course and approaching the slowest, the transition being critical and demanding. To see the board, he had to tear his eyes away from his path and sight left, down the steeply-banked, blurred pavement. Below him, tilted at a crazy angle by the combination of speed and perspective, stood Johnson with the 2'/2 by 4-ft. limegreen sign, visible for a split second, a midget in a blue uniform holding a bright postage stamp bearing the words “LAWSON” and “GAS.”

Lawson flicked his eyes forward, shook his helmet left-right, and was past, diving into Turn One.

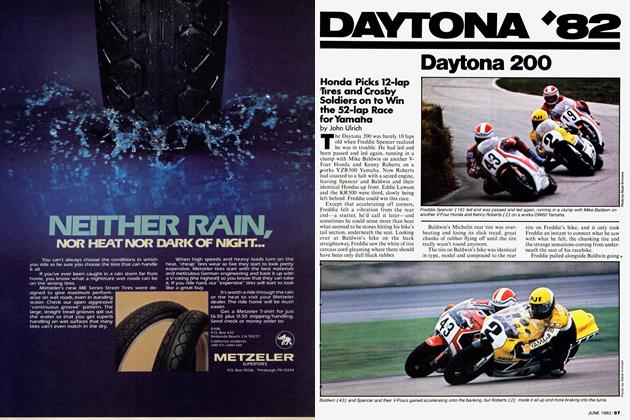

Nineteen laps into the 26-lap race, Lawson made his decision. He came to Daytona with a motorcycle built to finish, not win, and the Hondas were much faster. He qualified third fastest at 2:07, three seconds a lap slower than Freddie Spencer, who now fed. He qualified two seconds slower than Mike Baldwin, who now held third. He had come back from a disastrous, tire-smoking 20th-place start, charging hard and drafting and stuffing lap-after-lap until he raced Roberto Pietri for third place, losing on the banking every inch he gained in the infield.

Until the gas stops started. The Hondas couldn’t go IOO mi. on a single tank of gas, requiring a refueling stop. When Roberto pitted, Lawson was third; when Baldwin pulled in, Lawson was second, and when Spencer stopped, Lawson was close to the lead.

A pit stop would cost all the time he had gained, making him third for certain, maybe even fourth. But if, just if, the Kawasaki could go the distance without a stop . . .

It had been close in practice, but practice wasn’t racing, and the Kawasaki team had decided to play it safe with a pit stop.

So when Eddie came around on Lap 20, Johnson was still there with the bright green sign screaming “GAS.” Lawson shook his head again. And kept going.

He had other things to worry about, he would say later, his bike chattering in right turns, the wheels leaving the ground in tiny hops. Eddie somehow looked smooth and in control anyway.

Then there was the threat of Baldwin, coming from nine seconds adrift to seven to five, the numbers showing up on the Kawasaki pit board as +9; +7; finally + 5 with one lap remaining. Lawson’s lap times dropped from 2:08s and 2:09s and even two 2:10s to three straight 2:07s. The white flag flashed at the finish line. One lap to go.

“No problem,” thought Lawson. “It’ll go another lap.”

But it didn’t, instead sputtering, popping, missing and coasting to a halt at Turn Five, where the infield empties onto the west banking. Mike Baldwin sped by, hurtling onto the back straightaway, through the chicane, around the east banking, down the front straight and across the finish line.

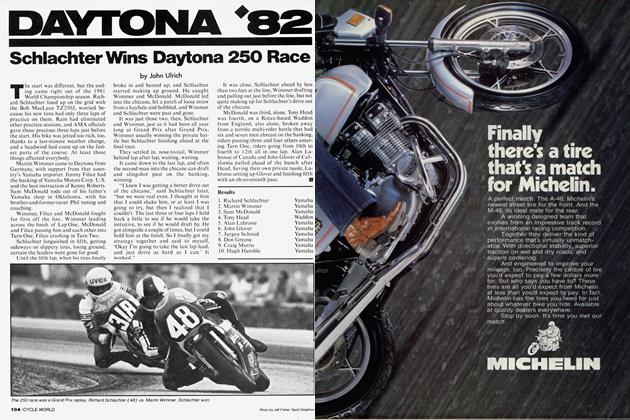

It was a surprise finish to a surprising race. Surprising because Wes Cooley finished fourth on an eight-valve Suzuki GS1000S. Cooley and hired-at-the-lastminute David Aldana were to ride new Yoshimura Katanas, but the 16-valve Suzukis never went more than five laps without blowing up with piston skirt and piston pin seizures. So Cooley went back to his 1981 Superbike. Aldana didn’t make the final event, failing to put together the required five laps in timed qualifying (which replaced the heat races used in previous years).

If there was a consolation for two-time Superbike Champion Cooley, it was that nobody rode an out-of-contention, oil-leaking bike harder. One lap he had photographers at Turn One gasping in disbelief as he bounced around barely upright, his body hanging in the air above the seat, bars wiggling furiously, tires skidding from his desperate attempt to make up for power by running in impossibly deep, impossibly fast. He almost crashed, somehow didn’t, and slowed down two seconds a lap from that point, but it was a gallant effort.

Surprising because Honda dominated so completely. It wasn’t just that Freddie rode so hard, the bike squirming and slithering and pitching off the corners. Freddie has always turned the gas on sooner, driving out harder even if to do so required going in slower, and his unique style is tougher on engines and suspension and tires, but deadly effective just the same.

What was surprising was the depth of the Honda team, Roberto Pietri leading the race through the infield on the first lap, with Baldwin first at the finish of lap one and Spencer leading the rest of the 100mi., 26-lap race.

Freddie pulled away, turning 2:04s and 2:05s to Baldwin’s 2:05s and 2:06s and 2:07s, Pietri and Steve Wise and Eddie Lawson racing for third for a time at 2:07s and 2:08s until Wise ran off the track, Lawson got away and Pietri pitted for gas. At the finish Freddie was cruising at 2:08s, and Baldwin chased Lawson with 2:06s.

The Team Honda depth came from horsepower, more horsepower than anybody ever got out of a Superbike before, and the power came from spending the most money, time and manpower ever committed to Superbike racing. Honda has made power before, but never this much and never with this much reliability. Honda’s Daytona 1982 was the result of buying what it took, from forged titanium connecting rods to titanium valves and valve spring retainers, 16-inch wheels and tires with new frames and frame geometry to match, cylinder heads ported by Vance & Hines, 36mm (with 31mm restrictors) EdVac flat-slide carburetors built by Bill Edmonson, you name it. The combinations were fine tuned and dialed in and tested with days and days of high-budget track time bought at Laguna Seca and Willow Springs and Daytona. Honda didn’t come to Daytona with untested bikes or equipment, nor just with adequately tested bikes. The Hondas were completely tested and proven, the riders seasoned with hundreds of laps on their bikes on the track they’d have to race on. Honda was ready.

Honda’s horsepower and track time made motocrosser-turned-dirt-trackerturned-road-racer Steve Wise an instant threat. Wise’s race for third ended when he overshot turn one (while drafting Pieri) and ran off into the grass. A few laps later Wise got sideways on oil, and, thinking the oil came from his own engine, stopped to look at his bike. Seeing nothing, he rode around and pulled into the pits, took off his helmet and declared that his bike had an oil leak. Told it didn’t, Wise put his helmet back on and took off the rejoin the fray. He finished eighth.

Wayne Rainey was fifth after a leisurely pit stop (Kawasaki teamsters had warned him not to come into the pits too fast, and he didn’t), Lawson officially sixth because he had lapped everybody except Rainey. Thad Wolff rode Matsu Matsuzawa’s Escargot GS1000 to seventh, first privateer. Harry Klinzmann challenged Wolff for first non-factory pilot before his Racecrafters-sponsored, Bob Endicott-tuned Lawson replica got a flat tire.

“If I had pulled in I would have been fourth or fifth,” said Lawson as the Honda team celebrated in victory circle. “As it is I got sixth and a lot of attention. If I had pulled in everyone would have thought nothing of it, just that I got smoked.

“It’s disappointing to ride that hard in the infield and lose it on the banking. It was probably harder on Wes because his bike was even slower than mine. Wes and I can ride with Freddie any day of the week and it’s disappointing not to have the equipment to do that. J

“Right now I’m sort of the bad guy in the pits.” Lawson shrugged, then looked off in the distance. “But if I had pulled it off...

RESULTS 1. Freddie Spencer Honda 2. Mike Baldwin Honda 3. Roberto Pietri Honda 4. Wes Cooley Suzuki 5. Wayne Rainey Kawasaki 6. Eddie Lawson Kawasaki 7. Thad Wolff Suzuki 8. Steve Wise Honda 9. Art Kowitz Kawasaki 10. Rusty Sharp Honda