Four-Into-Ones Over Los Angeles

The Startling Story of Pops Yoshimura

At that time, I was crazy," said Hideo "Pops" Yoshimura, talking about his days as a Japanese Navy flight engineer during World War II. His assignment was to lead young kamakazi pilots—who knew little more than how to take off and who couldn't navigate—through the predawn darkness to the U.S. fleet at Okinawa. "The kamakazi pilots followed my tail-light," said Pops. "At Okinawa, ships started to shoot at us, and the kamakazi pilots had no trouble finding the ships. We climbed up and watched. I was crazy then. I wanted to hit the big ships.”

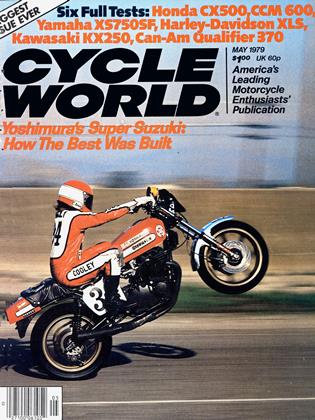

Pops Yoshimura, 57, is the most successful and well-known independent fourstroke road-racing tuner in the world. His machines dominate American Superbike Production races and his Suzuki GS1000 last year won an important eight-hour endurance race at Suzuka in Japan. There, the Yoshimura Suzuki lapped the RCB Honda of Christian Leon and JeanClaude Chemerin at the two-hour mark and went on to win by four laps over the second place TZ750 of David Emde and Isoyo Sugimoto. Third was a Yoshimura KZ1000 ridden by Graeme Crosby and Tony Hatton.

But if not for a few quirks of fate over 30 years ago, Hideo Yoshimura’s name might now only mark a gravestone. A fluke accident kept Hideo from being sent to Pearl Harbor after his graduation from pilot’s ground school at age 17. His parachute failed to open until he was very close to the ground in a training jump, and injuries from the impact ended his chances of getting a pilot’s license.

Hideo decided to become a flight engineer instead, a decision which led to the study of aircraft engines. He received his flight engineer’s license in 1941. Soon after, Japan was at war and young Hideo ended up flying cargo all over Southeast Asia.

“I flew 4000 hours during the war,” said Yoshimura, “and three times I just missed having to die. Twice American P-5 Is attacked us. We only carried pistols. One more time was bad, bad weather.”

In the closing stages of the war Yoshimura escorted kamakazis. Fate again intervened.

“Every day I was flying in a fast bomber,” said Yoshimura. “Every day is scary, much shooting, and I started to drink. I cannot drink now, but then I was a heavy drunkard every day. My stomach went bad, I spit blood. Two months before the end of the war, I went into the hospital for an operation. That two months I didn’t fly, most of my friends were shot down by American planes.”

The war ended and Americans occupied Japan. Yoshimura stayed home in Fukuoka City, Kyushu Island, and learned a little English. “Living was very hard,” he said. “No food. I started communicating with Gis, and GIs bring food, some fish or something. I make big trouble.”

Yoshimura was nicknamed “Pops” by American soldiers, and he founded a thriving black market business—which ended with a six-month jail term. Describing the intervening years as being empty, in 1955 Pops opened a foreign motorcycle dealership carrying BSA, BMW and Vincent. Most of his customers were G Is.

Soon road races were being held on the access roads around a nearby airbase, and Pops started hopping up machines. British bikes won most of the races until Honda introduced the CB72 and CB77.

“Honda Super Hawks beat the other bikes,” said Pops, “and GIs bought Hondas. For eight years, 1957 to 1965, we raced at that airbase.”

Honda was already involved in GP races and the rest of Japan knew nothing of the racing on Kyushu Island. When Honda built Suzuka circuit and hosted the first Suzuka 18-hour endurance race, no one paid attention to the Yoshimura team . . . until practice. Yoshimura bikes qualified fastest and ran one-two in the race until the second bike broke. The leading Yoshimura machine won.

“We beat Honda R&D team and Yamaha team,” said Pops. “We beat them all.”

The result was that Honda hired Pops to build machines for domestic races, in which entries were limited to productionbased motorcycles.

More than winning races in Japan, Pops was earning a name overseas. Soldiers returned home from duty in Japan with Yoshimura Hondas and parts. Late in 1970, the Yoshimuras sold—through a former GI—a Honda 750 racing engine to a prominent Honda dealer who sponsored Gary Fisher. At Daytona in 1971, Fisher led until the cam chain broke.

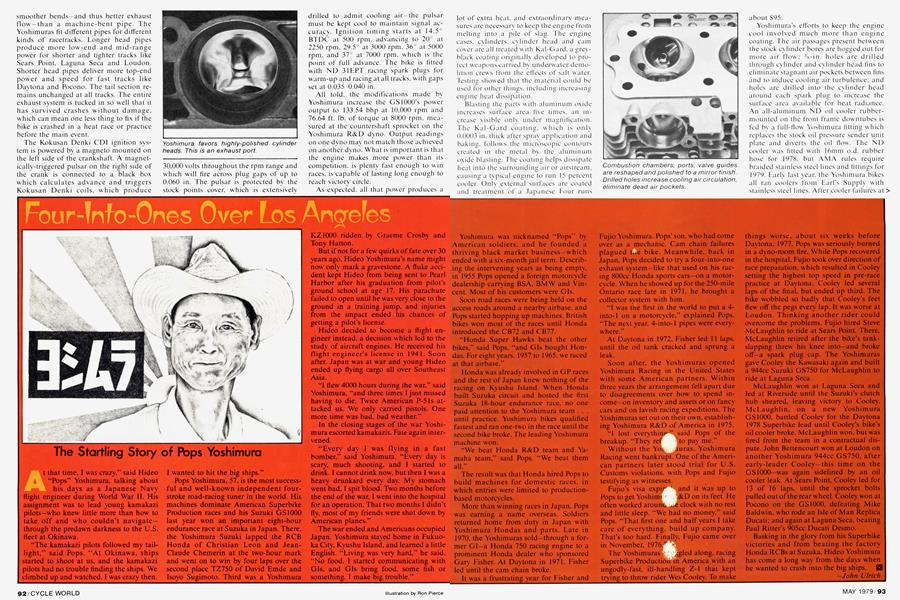

It was a frustrating year for Fisher and Fujio Yoshimura, Pops’ son, who had come over as a mechanic. Cam chain failures plagued t.,e bike. Meanwhile, back in Japan, Pops decided to try a four-into-one exhaust system—like that used on his racing 800cc Honda sports cars—on a motorcycle. When he showed up for the 250-mile Ontario race late in 1971, he brought a collector system with him.

“I was the first in the world to put a 4into-1 on a motorcycle,” explained Pops. “The next year. 4-into-l pipes were everywhere.”

At Daytona in 1972. Fisher led 11 laps, until the oil tank cracked and sprung a leak.

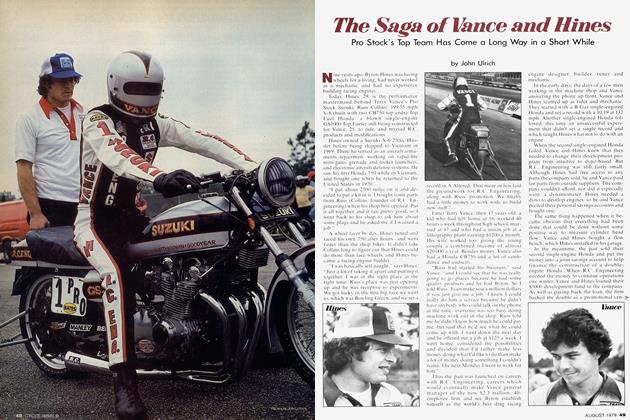

Soon after, the Yoshimuras opened Yoshimura Racing in the United States with some American partners. Within three years the arrangement fell apart due to disagreements over how to spend income—on inventory and assets or on fancy cars and on lavish racing expeditions. The Yoshimuras set out on their own, establishing Yoshimura R&D of America in 1975.

“I lost everythin? ” said Pops of the breakup. “They ref to pay me.”

Without the YOL auras, Yoshimura Racing went bankrupt. One of the American partners later stood trial for U.S. Customs violations, with Pops and Fujio testifying as witnesses.

Fujio’s visa expir 1 and it was up to Pops to get Yoshirm &D on its feet. He often worked arounc ¿,e clock with no rest and little sleep. “We had no money,” said Pops. “That first one and half years I take care of everything, build up company. That’s too hard. Finally, Fujio came over in November, 1976.”

The Yoshimuras ggled along, racing Superbike Production in America with an ungodly-fast, ill-handling Z-l that kept trying to throw rider Wes Cooley. To make things worse, about six weeks before Daytona. 1977. Pops was seriously burned in a dyno-room fire. While Pops recovered in the hospital, Fujio took over direction of race preparation, which resulted in Cooley setting the highest top speed in pre-race practice at Daytona. Cooley led several laps of the final, but ended up third. The bike wobbled so badly that Cooley’s feet flew off the pegs every lap. It was worse at Loudon. Thinking another rider could overcome the problems, Fujio hired Steve McLaughlin to ride at Sears Point. There, McLaughlin retired after the bike’s tankslapping threw his knee into—and broke off—a spark plug cap. The Yoshimuras gave Cooley the Kawasaki again and built a 944cc Suzuki GS750 for McLaughlin to ride at Laguna Seca.

McLaughlin won at Laguna Seca and led at Riverside until the Suzuki’s clutch hub sheared, leaving victory to Cooley. McLaughlin, on a new Yoshimura GS1000, battled Cooley for the Daytona 1978 Superbike lead until Cooley’s bike’s oil cooler broke. McLaughlin won, but was fired from the team in a contractual dispute. John Bettencourt won at Loudon on another Yoshimura 944cc GS750, after early-leader Cooley—this time on the GS1000—was again sidelined by an oil cooler leak. At Sears Point, Cooley led for 13 of 16 laps, until the sprocket bolts pulled out of the rear wheel. Cooley won at Pocono on the GS1000, defeating Mike Baldwin, who rode an Isle of Man Replica Ducati; and again at Laguna Seca, beating Paul Ritter’s 905cc Ducati Desmo.

Basking in the glory from his Superbike victories and from beating the factory Honda RCBs at Suzuka, Hideo Yoshimura has come a long way from the days when he wanted to crash into the big ships.

—John Ulrich