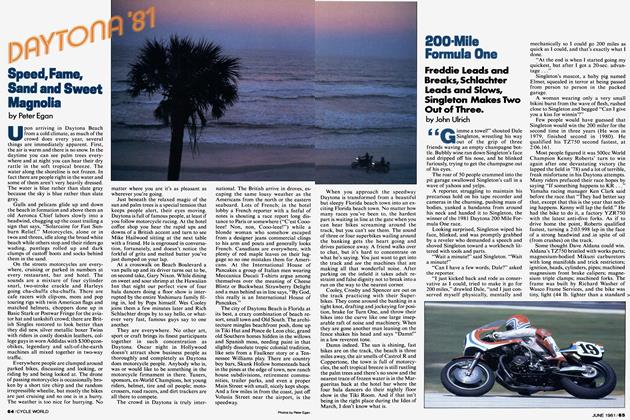

200-Mile Formula One

Freddie Leads and Breaks, Schlachter Leads and Slows, Singleton Makes Two Out of Three.

John Ulrich

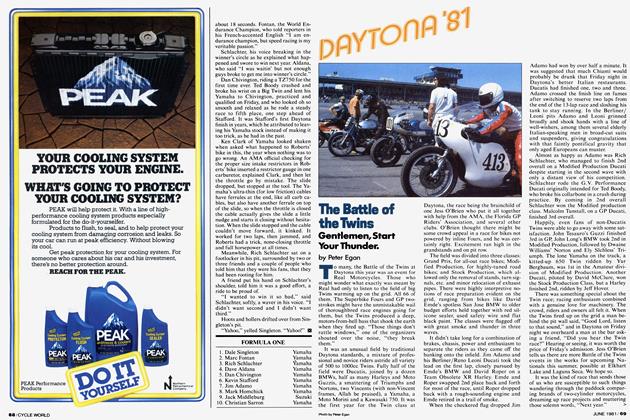

"Gimme a towel!” shouted Dale Singleton, wrestling his way out of the grip of three friends waving an empty champagne bottle. Bubbly wine ran down Singleton’s face and dripped off his nose, and he blinked furiously, trying to get the champagne out of his eyes.

The roar of 50 people crammed into the pit garage swallowed Singleton’s call in a wave of yahoos and yelps.

A reporter, struggling to maintain his precarious hold on his tape recorder and cameras in the churning, pushing mass of bodies, yanked a bandanna from around his neck and handed it to Singleton, the winner of the 1981 Daytona 200 Mile Formula One race.

Looking surprised, Singleton wiped his face, blinked, and was promptly grabbed by a reveler who demanded a speech and shoved Singleton toward a workbench littered with tools and parts.

“Wait a minute!” said Singleton. “Wait a minute!”

“Can I have a few words, Dale?” asked the reporter.

“I just kicked back and rode as conservative as I could, tried to make it go for 200 miles,” drawled Dale, “and I just conserved myself physically, mentally and mechanically so I could go 200 miles as quick as I could, and that’s exactly what I done.

“At the end is when I started going my quickest, but after I got a 20-sec. advantage . . .”

Singleton’s mascot, a baby pig named Elmer, squealed in terror at being passed from person to person in the packed garage.

A woman wearing only a very small bikini burst from the wave of flesh, rushed close to Singleton and begged “Can I give you a kiss for winnin’?”

Few people would have guessed that Singleton would win the 200 miler for the second time in three years (He won in 1979, finished second in 1980). He qualified his TZ750 second fastest, at 2:06.161.

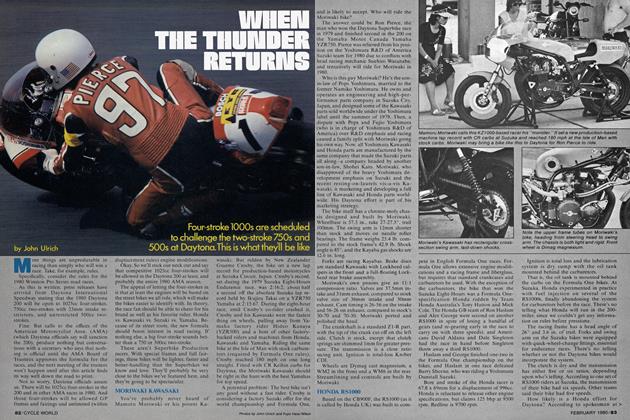

Most people figured it was 500cc World Champion Kenny Roberts’ turn to win again after one devastating victory (he lapped the field in ’78) and a lot of terrible, freak misfortune in his Daytona attempts. Many riders prefaced their race hopes by saying “If something happens to KR . . .” Yamaha racing manager Ken Clark said before the race that “They had better say that, except that this is the year that nothing happens. Kenny will lap the field.” He had the bike to do it, a factory YZR750 with the latest anti-dive forks. As if to drive home the point, Roberts qualified fastest, turning a 2:03.998 lap in the face of a strong headwind and .in spite of oil (from crashes) on the track.

Some thought Dave Aldana could win. Aldana’s TZ750 bristled with works parts; magnesium-bodied Mikuni carburetors with long manifolds and trick restrictors; ignition, heads, cylinders, pipes; machined magnesium front brake calipers; magnesium triple clamps; machined forks. The frame was built by Richard Washer of Wasco Frame Services, and the bike was tiny, light (44 lb. lighter than a standard TZ750), short and quick. The engine was the result of collaboration between Don Vesco and Bob Work (his bikes won under Steve Baker in 1977 and finished second with Ron Pierce in 1979). Washer handcarried the frame (as checked baggage) to Daytona, arriving Sunday. The engine was fitted Monday, and Tuesday was lost to finding and curing an ignition bug. Wednesday was amateur day, so Aldana got his first practice Thursday, riding four laps and then qualifying ninth at 2:09.037.

Freddie Spencer qualified his fourstroke Honda RSI000 third fastest, at 2:06.890. The four-stroke Yoshimura Suzukis of Wes Cooley and Graeme Crosby were fourth and fifth fastest (2:07.195 and 2:07.344), leading the TZ750s of twotime U.S. Road Racing Champion Rich Schlachter (2:07.44) and World Endurance Champion Marc Fontan (2:07.778). Boet Van Duimen qualified eighth on a TZ750 (2:08.558), followed by Aldana at ninth and Kevin Stafford (TZ750) at 10th (2:09.201).

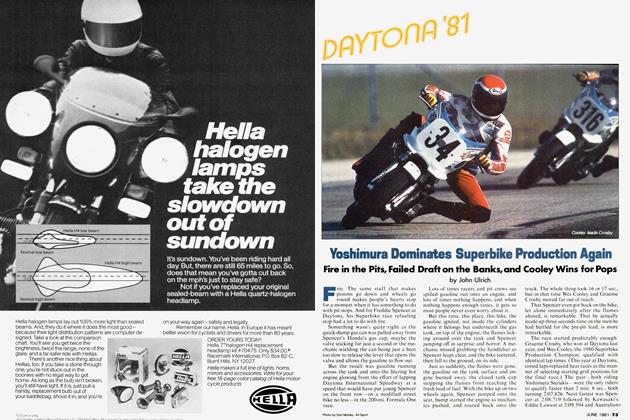

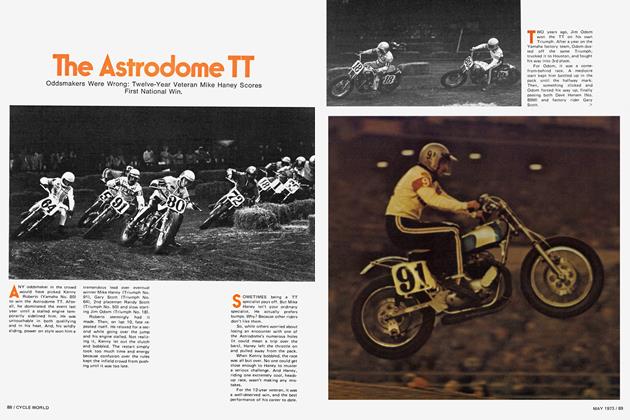

Cooley led the start, with Spencer right on Cooley’s rear wheel. The pair pulled ground on the two-strokes, and when they came onto the first banking (chased by Van Duimen, Crosby, Aldana, Stafford, Fontan et al.) Spencer powered past Cooley, then proceeded to build himself a larger and larger lead, turning 2:05 laps.

While Spencer worked at running away from everyone else, a spectator at the Turn Three top-of-third-gear kink waited for Roberts to make his move. The field came around the infield on the second lap, and the spectator turned to another and said “Now watch this. Nobody takes this turn like Kenny . . .”

He watched in amazement as Roberts entered the turn 10 mph faster than anybody could possibly take the curve . . . and ran straight out onto the grass, engine screaming as he frantically fought with the brakes and raised a huge cloud of dust and tried to keep from re-entering the track at Turn Four on a collision course with riders still on the pavement.

Roberts’ race was over, ending with stuck throttles just as Rich Schlachter’s race was beginning. Last year, Schlachter fried his bike’s clutch getting the holeshot, and retired in one lap. This year he swore not to do that again so eased out the clutch gently as he fed in the throttle—and promptly killed the engine. Jumping off to push, Schlachter got underway at the end of the first start wave and immediately abandoned his plans for an orderly, cautious approach at the beginning of the 200 miles. Instead he whipped into a series of 2:05 laps and sliced through the field, gaining rapidly on the leaders.

Schlachter was third and closing in three laps, behind Spencer and Cooley and ahead of Fontan, Singleton and Aldana. Crosby already had shifting trouble and would retire in another handful of laps.

By the fifth lap, Schlachter was second, and Cooley started to lose ground as his Suzuki overheated and slowed. At 10 laps, it was still Spencer alone in front; Schlachter, alone in second; Fontan and Singleton in tandem, racing for third; Cooley; Aldana. The 15th lap showed little change except that Spencer was farther out in front of Schlachter and Schlachter was farther ahead of Singleton, who had passed Fontan. Aldana was fifth, Christian Sarron sixth, Stafford seventh, Cooley eighth.

Aldana was riding around, he would say later, cruising. A main jet had fallen out of a carburetor in the final practice session the morning of the 200-mile race, and by the time Work and Vesco had diagnosed the problem, practice was over. The pair guessed at final jetting for the race, guessed on the safe, rich side.

So when Aldana got on the track, the bike—which had easily pulled 10,500 rpm in qualifying—would only touch 8500 rpm in the race. “It wasn’t runnin’ right,” Aldana would explain afterwards, “and every time something hasn’t been right and I tried real hard, it didn’t make any difference. So I just kicked back and rode around. I didn’t even try. Look at me, my hair’s not even wet; I didn’t even work up a sweat.”

Up front, Spencer was trying, and sweating, and it was paying off. But everything went wrong at the first of two scheduled gas stops. The engine bogged while gasoline was being forced into the fuel tank; lugged, then cleared out as Spencer left the pit.

For its last lap.

It threw a rod, opening a huge hole in the cases on the next lap. Spencer pulled into the pits, where the broken Honda deposited all its oil on the pavement.

Schlachter led, convincingly. He dove toward Turn One just after someone else had crashed, and ran over debris. His bike whipped sideways on the pit-side banking, flinging him up out of the saddle and off the footpegs. Schlachter held on and didn’t crash, but his forearms broke a section of plexiglass out of the windscreen.

With the chunks of plexiglass went the bike’s fuel tank breather hose, and gasoline sloshed out of the breather, was whipped inside the remains of the bubble, and Schlachter couldn’t see through the windshield anymore.

He could deal with that, peeking above the bubble, straining his neck muscles against the 170 mph wind blast.

But when second and third gears in the transmission lost teeth, Schlachter was forced to shift around the troubled gears, slipping the clutch out of turns. Which is why he slowed, and why Singleton overtook on the 37th lap, and pulled off into the distance ahead.

It took Fontan a few more laps to overtake and pass, and then he, too, was gone, and Schlachter was left alone, wondering if he could even finish the 52 laps in possession of third place.

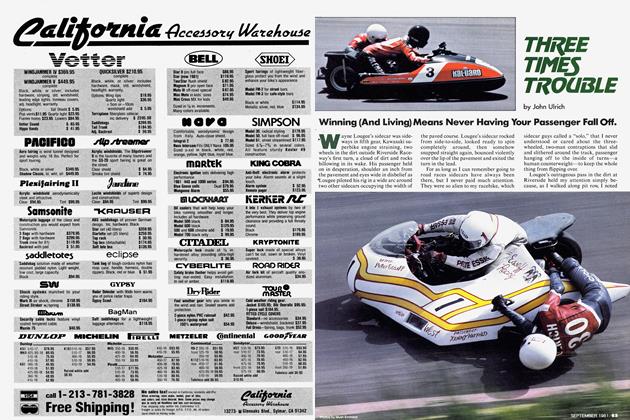

Cooley parked outside Turn Three, covered with oil from a broken-rod-induced hole in his bike’s cases. Christian Sarron ran off course into the haybales at the chicane, toppling over in slow motion and returning to the fray with a slightly-bent, slightly-wobbly TZ and a bunch of lost time.

Fontan was slow to catch Schlachter because he drove past his pit space on his second gas stop, and had to circle around in two inter-connected U-turns to find his mechanics and refueling rig. The error cost him 22 seconds. Maybe the race.

But maybe not, for Singleton came in for gas to find a wave of gasoline sweeping across the pit lane from a pit space near his, and he was forced to abort hiï» stup and take another lap while crew members desparately tried to control the spill from Cory Ruppelt’s quick-fill tower, which had malfunctioned. Singleton made it in and out the second time, and continued.

And so came the finish. Singleton, by > about 18 seconds. Fontan, the World Endurance Champion, who told reporters in his French-accented English “I am endurance champion, but speed racing is my veritable passion.”

continued on page 108

Schlachter, his voice breaking in the winner’s circle as he explained what happened and swore to win next year. Aldana, who said “I was waitin’ but not enough guys broke to get me into winner’s circle.”

Dan Chivington, riding a TZ750 for the first time ever. Ted Boody crashed and broke his wrist on a Big Twin and lent his Yamaha to Chivington, practiced and qualified on Friday, and who looked oh so smooth and relaxed as he rode a steady race to fifth place, one step ahead of Stafford. It was Stafford’s first Daytona finish in years, which he attributed to leaving his Yamaha stock instead of making it too trick, as he had in the past.

Ken Clark of Yamaha looked shaken when asked what happened to Roberts’ bike in this, the year when nothing was to go wrong. An AMA official checking for the proper size intake restrictors in Roberts’ bike inserted a restrictor gauge in one carburetor, explained Clark, and then let the throttle go by mistake. The slide dropped, but stopped at the tool. The Yamaha’s ultra-thin (for low friction) cables have ferrules at the end, like all carb cables, but also have another ferrule on top of the slide, so when the throttle is closed the cable actually gives the slide a little nudge and starts it closing without hesitation. When the slide stopped and the cable couldn’t move forward, it kinked. It worked for two laps, then jammed, and Roberts had a trick, none-closing throttle and full horsepower at all times.

Meanwhile, Rich Schlachter sat on a footlocker in his pit, surrounded by two or three friends and a couple of people who told him that they were his fans, that they had been rooting for him.

A friend put his hand on Schlachter’s shoulder, told him it was a good effort, a ride to be proud of.

“I wanted to win it so bad,” said Schlachter, softly, a waver in his voice. “I didn’t want second and I didn’t want third.”

Hoots and hollers drifted over from Singleton’s pit.

“Yahoo,” yelled Singleton. “Yahoo!”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontInnocence Vanquished, Fatherhood Victorious

June 1981 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1981 -

Department

DepartmentRoundup

June 1981 -

Competition

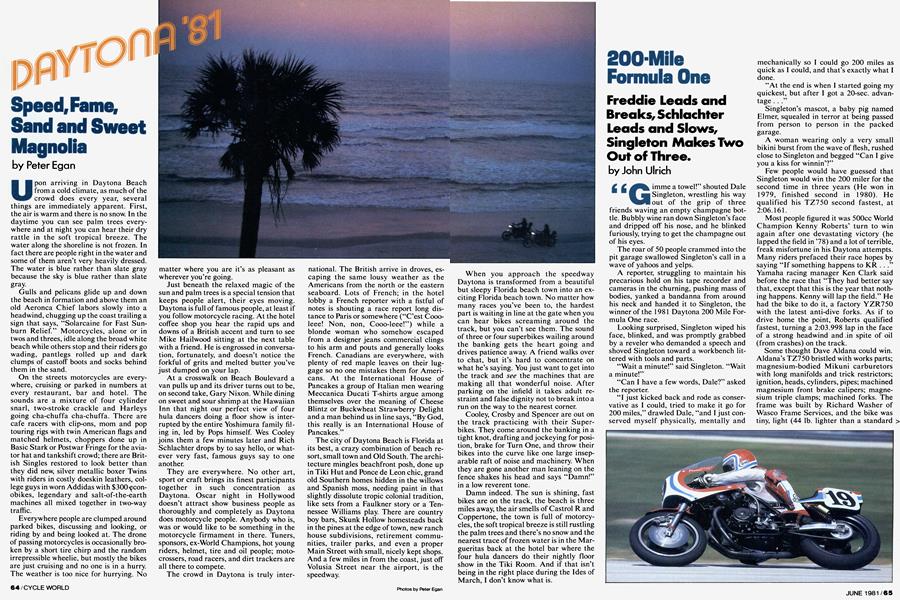

CompetitionDaytona'81 Speed, Fame, Sand And Sweet Magnolia

June 1981 By Peter Egan -

Daytona'81

Daytona'81The Battle of the Twins

June 1981 By Peter Egan -

Daytona'81

Daytona'81Supercross

June 1981