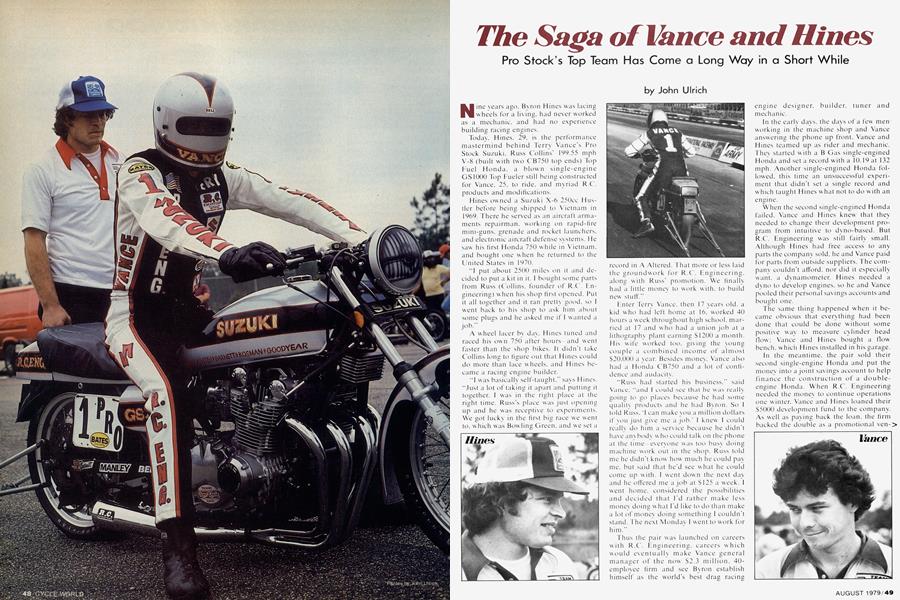

The Saga of Vance and Hines

Pro Stock’s Top Team Has Come a Long Way in a Short While

John Ulrich

Nine years ago. Byron Hines was lacing wheels for a living, had never worked as a mechanic, and had no experience building racing engines. Today, Hines, 29, is the performance mastermind behind Terry Vance's Pro Stock Suzuki, Russ Collins' 199.55 mph V-8 (built with two CB750 top ends) Top Fuel Honda, a blown single-engine GS1000 Top Fueler still being constructed for Vance, 25, to ride, and myriad R.C. products and modifications.

Hines owned a Suzuki X-6 250cc Hustler before being shipped to Vietnam in 1969. There he served as an aircraft armaments repairman, working on rapid-fire mini-guns, grenade and rocket launchers, and electronic aircraft defense systems. He saw his first Honda 750 w hile in Vietnam, and bought one when he returned to the United States in 1970.

“I put about 2500 miles on it and decided to put a kit in it. I bought some parts from Russ (Collins, founder of R.C'. Engineering) w hen his shop first opened. Put it all together and it ran pretty good, so 1 went back to his shop to ask him about some plugs and he asked me if 1 wanted a job.''

A wheel lacer by day. Hines tuned and raced his own 750 after hoursand went faster than the shop bikes. It didn't take Collins long to figure out that Hines could do more than lace wheels, and Hines became a racing engine builder.

“I was basically self-taught." says Hines. “Just a lot of taking it apart and putting it together. I was in the right place at the right time. Russ’s place was just opening up and he was receptive to experiments. We got lucky in the first big race we went to, w hich was Bow ling Green, and we set a record in A Altered. That more or less laid the groundwork for R.C. Engineering, along with Russ’ promotion. We finally had a little money to work with, to build new stuff."

Enter Terry Vance, then 17 years old. a kid who had left home at 16. worked 40 hours a week throughout high school, married at 17 and w ho had a union job at a lithography plant earning $1200 a month. His wife worked too. giving the young couple a combined income of almost $20.000 a year. Besides money. Vance also had a Honda CB750 and a lot of confidence and audacity.

“Russ had started his business," said Vance, “and I could see that he was really going to go places because he had some quality products and he had Byron. So I told Russ. 4 can make you a million dollars if vou just give me a job.' 1 knew I could really do him a service because he didn't have anvbodv who could talk on the phone at the time everyone was too busy doing machine work out in the shop. Russ told me he didn't know how much he could pay me, but said that he'd see what he could come up with. I went down the next day and he offered me a job at $125 a week. 1 went home, considered the possibilities and decided that I'd rather make less money doing what I'd like to do than make a lot of money doing something I couldn’t stand. The next Monday I went to work for him."

Thus the pair was launched on careers with R.C. Engineering, careers which would eventually make Vance general manager of the now $2.3 million. 40employee firm and see Byron establish himself as the world’s best drag racing engine designer, builder, tuner and mechanic.

In the early days, the days of a few men working in the machine shop and Vance answering the phone up front. Vance and Hines teamed up as rider and mechanic. Thev started with a B Gas single-engined Honda and set a record w ith a 10.19 at 132 mph. Another single-engined Honda followed. this time an unsuccessful experiment that didn't set a single record and which taught Hines w hat not to do w ith an engine.

When the second single-engined Honda failed, Vance and Hines knew that they needed to change their development program from intuitive to dyno-based. But R.C. Engineering was still fairly small. Although Hines had free access to any parts the company sold, he and Vance paid for parts from outside suppliers. The company couldn't afford, nor did it especially want, a dynamometer. Hines needed a dyno to develop engines, so he and Vance pooled their personal savings accounts and bought one.

The same thing happened when it became obvious that everything had been done that could be done without some positive way to measure cylinder head flow; Vance and Hines bought a flow bench, which Hines installed in his garage.

In the meantime, the pair sold their second single-engine Honda and put the money into a joint savings account to help finance the construction of a doubleengine Honda. When R.C. Engineering needed the money to continue operations one winter. Vance and Hines loaned their $5000 development fund to the company. As well as paying back the loan, the firm backed the double as a promotional ven ture, investing an additional $7000 over the two years it took Hines to finish the bike. The payoff came when the double-engine Top Gas Honda worked.

“Terry could ride good to start with and the motors were developing at about the same pace as his riding,” said Hines. “The next bike we built, a double-engined Honda, was so far ahead of the competition that it gave us lots of room for errors. If we didn't have the motors just right it would still run half a second quicker than anybody else.”

It was while working on the double that Hines learned his most prized and guarded secret, a modification he judges so critical that he will not discuss it nor allow' anvone to view the combustion chamber or intake tract of his cylinder heads. He has been able to transfer his discovery to Kawasaki and Suzuki heads with equal success.

As Vance tells it. the Honda had turned a best run of 8.90 at 155 mph. “One day Bvron was working on the flow' bench in his garage and he discovered a few things on the head that he thought would really work. We decided that maybe we should try the new modification and see if it worked. So we changed both heads on the bike —that’s all we changed, we didn’t change camshafts, we didn't change pistons. All we did was change the heads. The first pass we made the bike went 9.00 at 162 mph and all of a sudden the bike’s got a wheelie problem —I can’t keep the front end on the ground. If you can pick up 7 mph in the quarter with a slower E.T.. you've definitely picked up some horsepower. We put wheelie bars on for the first time and the bike w'ent 8.42 at 162 mph.”

The double was spectacularly successful, winning 22 out of 23 races. The single loss came when the magneto rotor on the rear motor broke during the burnout, and Vance lost by default. Five years after its last race, the bike’s record of 8.42 sec. at 162 mph still stands for double-engined gasoline-fueled motorcycles.

But as successful as the double was on the track, it won with such predictability that Vance and Hines didn’t attract much attention. People expected it to win, so when the machine went fast it was no big deal. Instead, press and spectator attention focused on the Pro Stock class, which allowed extensive engine modifications in a semi-stock-appearing chassis, and w'hich was filled by Kawasaki Z-ls turning highnine-second ETs.

Certain that they could win in Pro Stock. Hines built an 1162cc Honda CB750 in three weeks. In pre-race tests at a local strip, the bike turned 9.96.

At Ateo. New Jersey, for the next race, the R.C. Engineering Pro Stock Honda drew hoots of derision and laughter from competitors in the pits when Vance told them what the machine had done in testing. The man then dominating the class on a Z-l laughed and offered to bet $500 that the Honda wouldn’t turn in the ninesecond bracket, and another $500 that it wouldn't win the race. Vance declined to wager, but one of his friends did.

Vance qualified at 9.86, beat his vocal foe in the final round to win the race, and went on to take the Pro Stock championship for the year, setting the record at 9.74 at 137.19 mph.

In 1976 and 1977 Vance and Hines switched to a Kawasaki, setting the '76 record at 9.66 at 139.90 and lowering it to 9.38 at 144.00 in '77.

But even though they won the Pro Stock title twice with Kawasakis, Vance and Hines received no help from Kawasaki, and late in 1977 Vance went looking for sponsorship.

“I tried for 10 weeks to contact the guys in charge at Suzuki,” said Vance. “But finally I figured out what to do. I put the program together, put it all on paper, sent it to the head people and waited. After a couple of days I sent telexes to each one of them, explaining that my proposal was there and saying that I'd appreciate it if they would consider it. Finally all the guys from racing, advertising and marketing came down to the shop for a meeting in October, 1977. They asked if we would be willing to do this and that, we told them what we could do and would do and they said okay. The next week we were under contract and on the line.”

Vance and Hines won the Pro Stock championship with a GS1000 in 1978, and their current class record is 9.00 sec. at 147.05. The pair have been featured in a Suzuki commercial aired nationwide on prime-time television. Suzuki has printed Terry Vance posters and has sponsored a contest in which entrants can win a GS1000 painted to resemble Vance's. More than 120.000 people entered the contest for 10 Vance-replica GS 1000s.

Things have gone well for the pair. Their salaries at R.C. Engineering have doubled and tripled and doubled again as the company has grown. They receive additional income from Suzuki and other, smaller sponsors. They live less than a quartermile apart in a suburb of Los Angeles, near R.C. Engineering.

Vance is married and has one daughter, 5. H ines is married with a boy and a girl, ages 6 and 3. They own two houses .each, one to live in and another to rent. They fly to races, while an R.C. employee drives their bobtail truck carrying the Pro Stocker and spares.

At a night race with Vance and Hines, a reporter overhears bitter words. A competitor stands in the flood of fluorescent light spilling out of the spacious workshop interior of their truck. The man works his jaw and stares at the truck, the bike, the spare parts, the AC generator powering the lights. “If only I had that kind of support,” he mutters. “No wonder they win races.”

The competitor walks off. The reporter can't help but think back to the days when Byron Hines laced wheels and Terry Vance signed on to answer the phone.