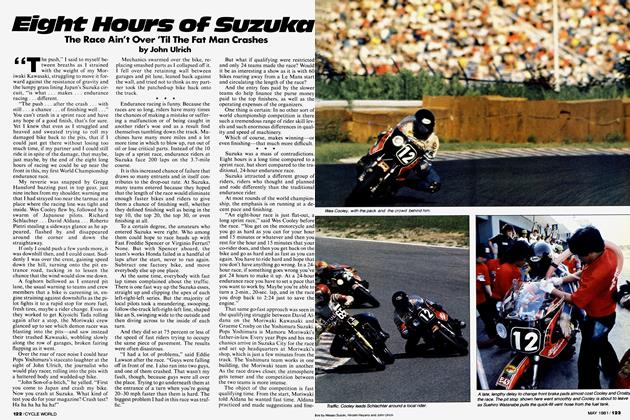

Bad Brad Lackey--No.2 and Trying Harder

America's Best Hope for an Open Class World Champion Challenges Heikki Mikkola at the U.S. Grand Prix at Carlsbad

John Ulrich

Bradley Gene Lackey, 25, has pursued the 500cc Motocross World Championship for six years. He could have earned big money during that time, if only he had stayed in America and raced AMA Nationals for a large Japanese firm. Instead, Lackey chose the hard way, heading for the motocross homeland before it was fashionable, challenging the European masters on their own turf: The Grand Prix circuit.

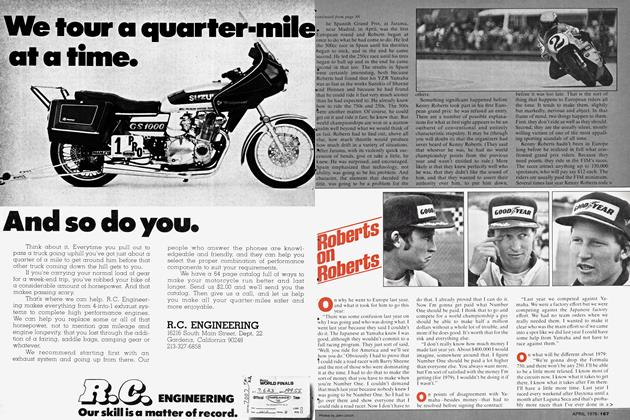

He started out with Kawasaki in 1972, winning the AMA 500cc Championship, and headed for Europe in 1973. That year, still on Kawasaki, Lackey finished the year ranked 13th in the World Championship. He was 10th at the end of 1974, his first season on Husqvarna; 6th in 1975; 5th in 1976. Lackey switched to Honda for 1977, finishing 4th.

1978 was Lackey’s best year. Still riding for Honda, he finished second in the point standings behind reigning champion Heikki Mikkola. Throughout the season, the pair of Lackey and Mikkola often ran off in a private battle that left the other riders far behind. At season’s end, Mikkola had 299 points, scored with 14 moto wins, two 2nds, six 3rds and one 6th. Lackey finished with 214 points tallied with four wins, 10 2nds, two 3rds, one 4th and one 5th, with three DNFs and two DNSs. Five-time World Champion Roger DeCoster was third with 172 points.

But Lackey’s end-of-season totals didn’t accurately reflect how much competition he gave Mikkola. For example, when the 500cc motocross circuit came to Carlsbad, Calif., for the U.S. Grand Prix, Lackey had a legitimate shot at taking away Mikkola’s title. Before Carlsbad, Mikkola had 21 points over Lackey, 147 to 126. With first place in a moto paying 15 points and second paying 12 points, Lackey would have had to beat Mikkola seven times to come even in points. But if Mikkola failed to finish just one moto, and if Lackey could win that moto, the margin would narrow to seven points. Three moto wins could give Lackey the points lead.

That’s not the way it happened. Mikkola had no failures, and crossed the finish line in front. Lackey’s bike lost its chain twice in the first Carlsbad moto, once while Brad led on the first lap, again as he charged through traffic in a desperate effort to make > up positions. Lackey retired. Mikkola won.

In the second moto in California, Lackey challenged and challenged again, closing right up on Mikkola’s rear wheel, charging, stuffing a wheel in . . . but ultimately failing. Mikkola wen again, Lackey second, far ahead of third place. So went the season.

Contract negotiations between Lackey and American Honda, his sponsor, broke down at the end of 1978. Before his contract with Honda had expired. Lackey had already announced his intention to sign with Kaw'asaki for 1979. His actual signing with Team Green wras announced by double-page, full-color advertisements placed by Kawasaki, headlined “What made Brad Lackey give the Reds the blues? The Kawasaki Greens.” The advertisements showed Lackey being tailor-fitted with Team Kawasaki leathers and jersey, while his red, white and blue Team Honda riding outfit hung forlornly over a coat rack.

“That particular ad,” said Lackey before leaving for his European debut with his new Kawasakis, “has done more for me than Honda’s PR department did in two years. That’s one of the major reasons I found problems working things out with Honda. They just weren’t into promoting the riders. Honda’s going to be in business for a long time, but Brad Lackey the racer isn’t going to be racing forever. I need exposure to help me further my career in some field, so I can make a living after I quit racing. I was really serious about that and Honda didn't agree. We couldn’t come to terms.

“I knew' that since I had finished second in 1978 that there might be some other offers coming in by the time I got back to the States. I tried to explain to Honda that that was probably going to happen. I wanted to negotiate my contract for 1979 before the Trans-AMA started (in the United States). I pushed that point to Honda Japan and to American Honda quite a bit before I came home. But when I got home, I couldn’t get a meeting. I couldn’t get anyone to listen to me or to try to resolve my contract. Everybody at Honda w'as just kind of putting me off.

“In the meantime, Kawasaki started talking to me. If Honda had gotten the contract done when I w'anted it done, I’d still be riding a Honda. But when Kawasaki came in and we got to talking, I found out how' serious they were about winning the World Championship, how much they wanted to do it. Honda was just kind of sitting around, saying that maybe they’d have the same bikes that they had last year—they’re not really moving. But Kawasaki’s working really hard and all the engineers are ready to w'ork all night long to make any changes we need. That got me interested.

“We started talking financially and everything sounded good, and then we discussed the PR aspects. I still went back to Honda and said to them ‘These other guys want me to ride for them and I need this and this and this’ (to remain with Honda). And Honda said ‘We can’t give you any PR, we can’t promise this, we can’t use you in any advertisements, we can’t do any commercials with you.’ In the meantime Kawasaki is saying they’ll do the kind of stuff that we’re already seeing them do now. I tried to work it out with Honda. I tried everything I could to get Honda to resolve the disputes, and they wouldn’t listen to me. So I signed with Kawasaki.” Lackey’s contract with Kawasaki calls for him to race two years with a third-year option—that is, he’ll ride the third year if both he and Kawasaki representatives agree that he should.

“My plan is to win the World Championship this year and regain it the following year, then stop and try to go into some kind of filming or commercials. Like Bruce Jenner. He worked 10 years to become decathalon champion, worked all that time and didn't get too much. Then he’s the champion and doesn't have to win anymore. That's my plan.”

Obviously, Lackey is confident. He rode prototypes of the Kawasaki GP bike before signing his contract. “The basic design is all there,” Lackey said after one test session on an early version of the 420cc machine. “I’m just making personal changes, the type of steering that I like, head geometry and trail, and travel. We’ll change the engine, make it a little bit different size. We’re still making engine changes, and we’ve been changing heads. It has plenty of horsepower. The main problem we have is trying to mellow it out wffiere it has nice and smooth power. We’ll probably put a four-speed gearbox in it.” Lackey left for Europe in wffiat he called the best physical shape he has ever been in. He weighed 179 pounds, up from his previously-normal 165 pounds, and none of the weight looked to be fat. The difference, according to Lackey, came from a w'inter conditioning program supervised by Dean Miller, a certified trainer w'ith a masters degree in athletic training and sports medicine from Arizona State University. The program, said Lackey, improved his overall conditioning and also concentrated on repairing ankle injuries suffered during 1978.

continued on page 122

continued from page 93

“I've worked a lot harder than I have in the past,” said Lackey. “I'm running five miles every day. doing power weight training and a lot of isometric stuff. When I get, to Europe I’m going to be in the best shape I've ever been in. I am more confident and that's the main thing. My confidence has just not been up to par in the past. But now. looking at everything realistically. I can actually win. Besides that. I'm more hungrv to win this year for some reason. Probably because it's getting to the point" that I better win and it's going to have to happen.

“I've gotten better every year that I've been riding the GPs and there's no reason for me to stop getting better at this point.. 1977 was the first year for Heikki on a Yamaha, and everybody said that he wouldn't do any good because he had a new bike and had just gotten back into the 500cc class. He had a good year and just smoked everybody really easily. He was untouchable. He could sit on the seat, ride, around and win without even getting out of control. Then 1978 came along and I was pushing him a lot more than he was pushed the vear before. He was riding harder, taking a lot more risks and getting out of control. I'd hear from someone in my pits ‘Oh man. Heikki just barely made it. almost flipped over. I don't know how he hung on. maybe just because he's a Hercules.'

“So that was the difference between^ 1977 and 1978. All I can say is that 1979 is again another year. I’ve learned more. I'm going to be faster. I'm already as fast, or faster, than Mikkola in a lot of places. It's just that he’s really built strong and he can ride on the limit when he has to. He doesn't make any mistakes and his bikes never breaks. That's a hard combination to beat. But I’m going to be riding faster and I have complete confidence in my mechanic and my new bike. I think I can« win—without any bad luck. Realistically. Heikki is going to be the main guy. If I beat him. I’ll be World Champion, and that’s all I’m worried about.”

Bill Buehka wrenched Lackey’s Honda in 1978, but Buehka stayed with Honda to tune for Britisher Graham Noyce when, Lackey went to Kawasaki. So Lackey recruited Steve Stasiefski as his mechanic. In his first year on the GP circuit, Stasiefski— formerly a mechanic for Maico’s U.S. distributor-tuned and transported West German Herbert Schmitz’s Maico without mishap—Schmitz finished fourth in Grand Prix standings.

“I was really impressed when I saw the way he (Stasiefski) handled it all by himself last year.” said Lackey. “He was always there in time, didn't complain too much and did his job. I really didn't know him that well. I had just seen that he had done a good job. Then he went with me to Japan and I was really impressed and amazed by how much he knew, how well he could work with any part of the bike—the suspension. the motor, the gearbox. He knew so much about every aspect of the motorcycle. I'm happy to have him. He’s got a new truck and everything he needs. He’s happy as can be and a good outlook for him is going to make a big difference. We're ready.”

As ready as Lackey is. not everything is peaches and cream, not even with the backing of the Kawasaki factory. Kenny Roberts was disappointed with the start money he received during the 1978 season. But at least for 1979 Roberts is guaranteed—as reigning 500cc road racing champion—a tenfold increase in the FIM minimum starting money. FIM World Championship motocross not only has a lower minimum—$ 150 versus road racing's S200—but there is no increase in the minimum based on the last season's rankings. The minimum stays at S150 for everybody, including the World Champion. >

“We get $150 start money,“ said Lackey. “If you won both motos of a GP you'd win $500-$600 maybe. So you don't get any money there. If you w in the World Championship and you have a factory ride, your company will give you some money, but it's not that much. If you get second, you’d probably get nothing. People talk about the great big salaries all the motocross riders make, but they fail to realize that you're traveling in Europe, spending al? kinds of money. You're never at home. You're working from 8:00 in the morning to 8:00 every night. You’re going wide open trying to do the best you can and working all the time at it. and you go to the races and w in and make $750. You've got to have somebody paying you some money somew here because you couldn't afford to do it if you didn't.

“Let's take Kenny Roberts for example. He went to Europe and won the 500cc roac? racing championship, something no American has ever done before. When he goes to an international race—a race not on^ the GP circuit, a race he doesn’t have to attend —he'll get maybe $20.000 start money. On some weekends when there aren't Grands Prix he goes and gets that $20.000. Where the motocross guy, if he’s a hero, rides an international race and gets $1000. A motocross guy gets pretty burned sometimes. He doesn't get nearly what any of the other motor sports guys get. I don't know what those Formula One guys get for winning a GP. but I'm sure it's some, money. Sure, we don't have the danger involved that they do. but you know it should be worth more than $150 start money.”

Lackey. The Great American Motocross Hope. The man who has come closer to the 500cc World Championship motocross title than anyone else from the United States.

For most Americans, the only opportunity to see Bad Brad Lackey race Mikkola and the others will come at the U.S. 500cc Grand Prix at Carlsbad on June 10. 1979. By then, we'll know whether or not Lackey can do it. g