RIDING THE NSR

MICK DOOHAN FOR A DAY

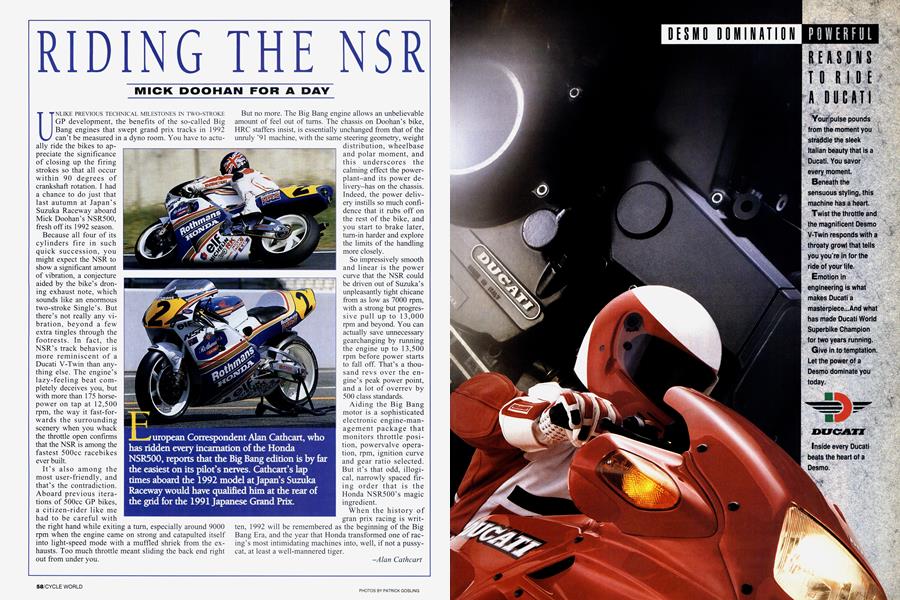

UNLIKE PREVIOUS TECHNICAL MILESTONES IN TWO-STROKE GP development, the benefits of the so-called Big Bang engines that swept grand prix tracks in 1992 can’t be measured in a dyno room. You have to actually ride the bikes to appreciate the significance of closing up the firing strokes so that all occur within 90 degrees of crankshaft rotation. I had a chance to do just that last autumn at Japan’s Suzuka Raceway aboard Mick Doohan’s NSR500, fresh off its 1992 season.

Alan Cathcart

Because all four of its cylinders fire in such quick succession, you might expect the NSR to show a significant amount of vibration, a conjecture aided by the bike’s droning exhaust note, which sounds like an enormous two-stroke Single’s. But there’s not really any vibration, beyond a few extra tingles through the footrests. In fact, the NSR’s track behavior is more reminiscent of a Ducati V-Twin than anything else. The engine’s lazy-feeling beat completely deceives you, but with more than 175 horsepower on tap at 12,500 rpm, the way it fast-forwards the surrounding scenery when you whack the throttle open confirms that the NSR is among the fastest 500cc racebikes ever built.

It’s also among the most user-friendly, and that’s the contradiction. Aboard previous iterations of 500cc GP bikes, a citizen-rider like me had to be careful with the right hand while exiting a turn, especially around 9000 rpm when the engine came on strong and catapulted itself into light-speed mode with a muffled shriek from the exhausts. Too much throttle meant sliding the back end right out from under you.

But no more. The Big Bang engine allows an unbelievable amount of feel out of turns. The chassis on Doohan’s bike, HRC staffers insist, is essentially unchanged from that of the unruly ’91 machine, with the same steering geometry, weight

distribution, wheelbase and polar moment, and this underscores the calming effect the powerplant-and its power delivery-has on the chassis. Indeed, the power delivery instills so much confidence that it rubs off on the rest of the bike, and you start to brake later, tum-in harder and explore the limits of the handling more closely.

So impressively smooth and linear is the power curve that the NSR could be driven out of Suzuka’s unpleasantly tight chicane from as low as 7000 rpm, with a strong but progressive pull up to 13,000 rpm and beyond. You can actually save unnecessary gearchanging by running the engine up to 13,500 rpm before power starts to fall off. That’s a thousand revs over the engine’s peak power point, and a lot of overrev by 500 class standards.

Aiding the Big Bang motor is a sophisticated electronic engine-management package that monitors throttle position, powervalve operation, rpm, ignition curve and gear ratio selected. But it’s that odd, illogical, narrowly spaced firing order that is the Honda NSR500’s magic ingredient.

When the history of gran prix racing is written, 1992 will be remembered as the beginning of the Big Bang Era, and the year that Honda transformed one of racing’s most intimidating machines into, well, if not a pussycat, at least a well-mannered tiger.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontOr Best Offer

February 1993 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Ducks of Autumn

February 1993 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCComputers Vs. Intuition

February 1993 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1993 -

Roundup

RoundupIndian Wars Continue

February 1993 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupOxygenated Fuel And the Motorcyclist

February 1993 By Kevin Cameron