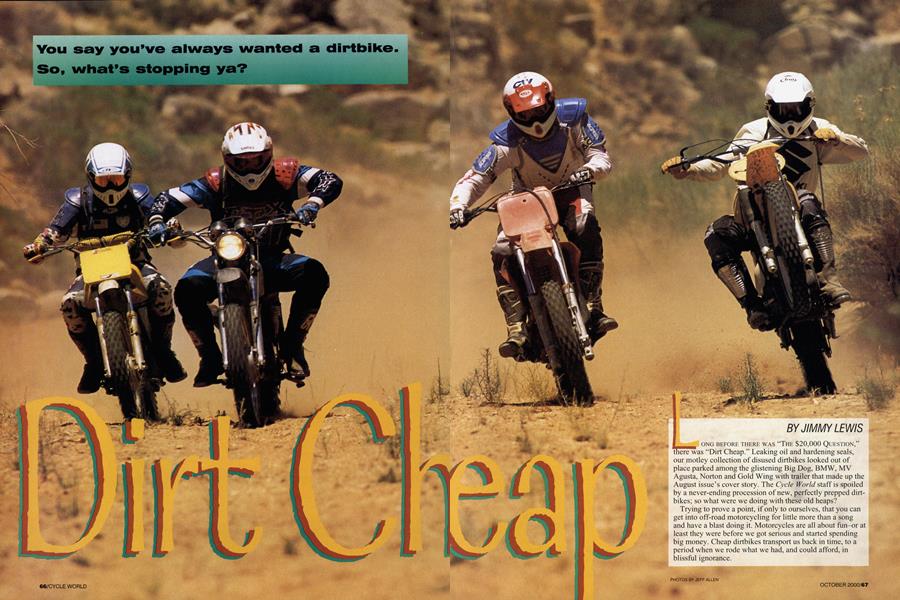

Dirt Cheap

You say you've always wanted a dirtbike. So, what's stopping ya?

JIMMY LEWIS

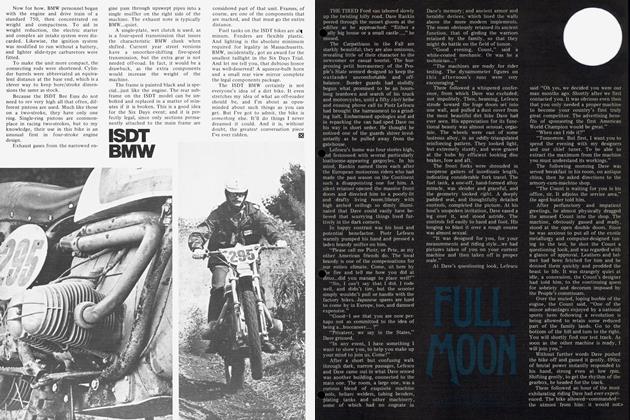

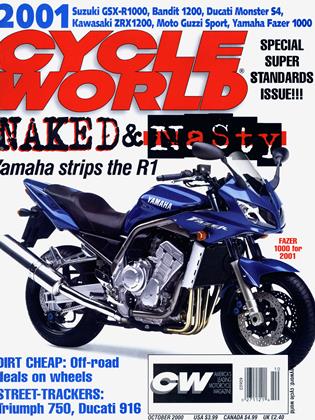

LONG BEFORE THERE WAS "THE $20,000 QUESTION," there was "Dirt Cheap." Leaking oil and hardening seals, our motley collection of disused dirtbikes looked out of place parked among the glistening Big Dog, BMW, MV Agusta, Norton and Gold Wing with trailer that made up the August issue's cover story. The Cycle World staff is spoiled by a never-ending procession of new, perfectly prepped dirtbikes; so what were we doing with these old heaps?

Trying to prove a point, if only to ourselves, that you can get into off-road motorcycling for little more than a song and have a blast doing it. Motorcycles are all about fun-or at least they were before we got serious and started spending big money. Cheap dirtbikes transport us back in time, to a period when we rode what we had, and could afford, in blissful ignorance.

This is nothing new, of course. A couple of decades ago, CWs own Peter Egan and Allan Girdler tossed around the idea of starting a club for riders of cheap dirtbikes. Peter suggested the acronym UFO (Under Five-hundred-dollar Offroad), which just seems wrong to describe the stone-slow ’70s Honda XL250 and 350 the pair rode. Then again, maybe that was the point.

Anyway, this story began when I acquired a 1976 Suzuki RM370 for free, and boasted of my find to Executive Editor Brian Catterson at the office the next day.

“How about a story on a free dirtbike?” I suggested.

“There’s no such thing,” Catterson shot back. “At the very least, you’ll need to buy tires or a chain or something.”

By the following Monday, however, he’d changed his tune, something to do with the 1984 Cagiva WMX125 he’d picked up for $100 over the weekend. There might not be such a thing as a free dirtbike, but an inexpensive one... Heck, you see them advertised for a couple of hundred bucks in the paper all the time.

And that’s when we came up with the idea for “Dirt Cheap.”

The rules were simple: Initial purchase price would be limited to $300, and total expenditure following whatever replacement parts were necessary could not exceed $500. Other staffers were quick to jump on board, and we then planned and planned and re-planned our group ride, only to abort when one editor or another bailed out to attend the next wine-and-cheese streetbike introduction.

A year or so later, during a Thursday-aftemoon editorial meeting, we finally said to hell with it and decided that no matter what, we were leaving on Monday morning. I mapped out a two-day loop, and with little more in the way of instructions than to meet me at the office with their bikes, gear and sleeping bags, three other loyal staffers showed up sporting junk. In addition to my Suzuki, there was Catterson’s Cagiva, Assistant Art Director Brad Zerbel’s 1973 Yamaha MX250 and Sports Editor Mark Hoyer’s 1975 Honda MT250 Elsinore.

The CW shop was buzzing with last-minute activity. Catterson was attempting to perform an emergency shockoil transfusion. Zerbel was jerry-rigging a muffler mount. And Hoyer, who’d just purchased his bike on Friday, was getting a head-start on his restoration project, barely peeling his clenched fingers from the steel wool and polish in time to leave.

A hairdryer-like, 100-degree breeze greeted us in the Mojave Desert, a far cry from the freezing temperatures we endured there during last winter’s Ghost Town Tour. Obviously concerned about his Italian 125 going the distance in the desert heat, Catterson inquired about the route.

“We’re going to ride 60 miles to my buddy’s cabin, spend the night there, and then ride back in the morning,” I informed him.

“Sixty miles?/” Catterson repeated, now even more concerned. “I’ve barely ridden this thing around the block.”

“No worries, the first 20 miles are wide-open graded road,”

I replied, doing little to soothe his nerves. After all, what could be better for shaking loose rust than a little top-gear spin?

All of a sudden, everyone was asking about premix ratios, but amazingly, all four bikes passed the acid test. In fact, they cruised at a pretty good clip without so much as a

hiccup. That is, until we hit a few bumps. Then, things started to happen.

My ultra-trick air shocks blew out, Brian’s left sidepanel fell off, Brad’s carburetor was burbling and Mark found out why modem dirtbikes have more than 4 inches of rearwheel travel. So we plonked along into Jawbone Canyon, parked beneath the California Aqueduct pipe-the only shade for 100 miles-and regrouped.

I’d packed the Suzuki’s stock shocks because I suspected this would happen. And fortunately for Brad, I’d packed a few Mikuni jets, too. Two sizes leaner and the Yamaha ran

as crisp as a month-old apple. A few gallons of water and Gatorade later, our crew was ready to resume riding.

We tackled a few soft, sandy hillclimbs, then headed toward Dove Springs, where the graded roads gave way to long, fast (and sometimes deep) sandwashes. Did I mention that they went uphill? Brad’s Yamaha was being choked to death by the muffler I’d lent him, and would barely get out of its own way. And Mark seemed intent on protecting his investment, coaxing the bare minimum of performance from his Honda. I, on the other hand, had no emotional attachment to my Suzuki, and felt the need to play J.N. Roberts and Malcolm Smith (never mind that they rode Huskys). So I pinned the mighty 370 and let it all hang out.

Never one to back down from a challenge, Catterson and his liquid-cooled 125 began chasing my dust. Soon, the pinging and rattling from my RM’s air-cooled cylinder inspired in me a small amount of conservatism-meaning I realized it was a long hike out-and I slowed ever so slightly. But Brian held it wide-open, and tapping the peak performance of his tiddly 125, pulled up alongside.

So there we were, ripping up the sandy wash side by side, showering each other in roost from our worn-out knobbies, when all of a sudden a horrible Wuuurrrppp replaced the usual two-stroke scream. We glanced at each other, wondering whose bike just did that, and surprisingly it was Brian’s water-pumper that was the culprit. But as quickly as the

Italian steed tried to make cylinder and piston one, it came back to life. Credit the ’90s technology of the sweetsmelling Castrol two-cycle oil we were burning for sparing the ’80s metal.

We finished off the day by heading up an old jeep road with a few steep climbs and the odd challenging rocky section. Here’s where Hoyer’s restoration project got a bit more expensive-or did it just gain character? Depends on how you see it. All the clutch work in the world couldn’t save the bogging Honda in a slippery rock section, and the bike wound up wedged upside-down between two boulders. Mark carefully calculated the value of the damaged parts and then, paying special attention to his MT’s cherry gas tank, figured out the least expensive way to right the bike. After tying up the broken speedometer cable, and with the front brake lever now sticking straight out, he was off again.

Brad’s bike went all the way up the hill in first gear, throttle pegged, engine sucking air, and aided by the occasional dog paddle. He tried upshifting, but found it best to over-rev the engine so it didn’t have an opportunity to bog. Brian, meanwhile, was busy holding his 125’s throttle to the stop, fanning the clutch, shifting up and down, and generally wishing he’d bought a larger-displacement bike. Maybe converting that Cagiva 500 of his into a SuperTT racer wasn’t such a good idea after all?

After a night spent drinking beer, eating tacos and making old-bike noises in our sleep, we embarked on a return route with an even higher fun quotient. For me, anyway.

Returning down the steep jeep road was a testament to how far brakes have come, the drums on our bikes barely capable of slowing our descent. And at the beginning of “Cow Pie Wash,” where a fair amount of clutch work and tight, technical turning were required, we were reminded of the progress in those areas as well.

Three of our four bikes were twin-shockers from what motocrossers call the Vintage or Evolution eras. Because of their low centers of gravity and proximity to the ground, regaining control on these machines was much easier than on a sky-high modem bike. It’s just that with high-effort steering and clutch pulls, punchy yet lazy power characteristics and little (if any) help from the suspension, they were more likely to get out of control in the first place!

Amazingly, our quartet of sorry steeds never skipped a beat. In fact, we had more trouble with our chase truck, a late-model Dodge Dakota, which was hard-starting and got two flat tires. And then there was the Y2K Suzuki DR-

Z400E ridden by our balance-challenged photographer Jeff Allen, who endoed into a cow pie puddle, then tipped over on a steep downhill, punching a hole in the bike’s clutch cover. Hey Jeff, you stink!

Nearing the end of our trip, on a long Mojave powerline road, Brian and I threw restraint to the wind to see if our time machines could really put out. And they did. Even with all the foul noises coming from the incredibly unbalanced, lightly muffled, surely air-leaking, corroded, rusted and in many places cracked motor, my Suzuki ran hard! Same with Catterson’s pint-sized Cagiva, which he frankly expected to seize while pinned in sixth, but instead surprised him by snapping its clutch cable just a few miles from the end of our ride. No biggie.

I always knew we’d have fun riding these old bikes, but I never imagined we’d get so much satisfaction out of fixing all the little problems that cropped up along the way. In the process, I gained a newfound respect for the men who rode and raced these machines. And I even began to understand why some were so resistant to the changes that helped dirtbikes evolve into what they are today. But I got the biggest kick out of the fact that our four bikes were acquired for a grand total of $425. Anyone who says they can’t afford a dirtbike obviously can’t afford to have a good time!

One precaution, though: You will get hooked and invariably start buying newer and better dirtbikes.

Don’t say we didn’t warn you.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontRally At Red Rocks

October 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsLate-Braking News

October 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCMaking It Happen

October 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

October 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupSpied! Suzuki's Big-Bore Blaster

October 2000 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupGood-Bye, King of the Roads

October 2000 By Brian Catterson