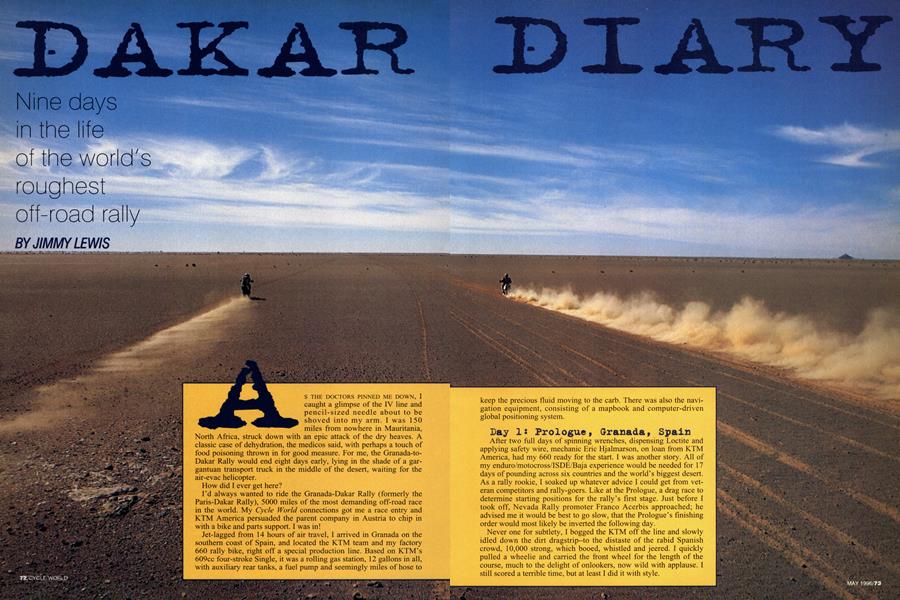

DAKAR DIARY

Nine days in the life of the world's roughest off-road rally

JIMMY LEWIS

AS THE DOCTORS PINNED ME DOWN, I caught a glimpse of the IV line and pencil-sized needle about to be shoved into my arm. I was 150 miles from nowhere in Mauritania,

North Africa, struck down with an epic attack of the dry heaves. A classic case of dehydration, the medicos said, with perhaps a touch of food poisoning thrown in for good measure. For me, the Granada-toDakar Rally would end eight days early, lying in the shade of a gargantuan transport truck in the middle of the desert, waiting for the air-evac helicopter.

How did I ever get here?

I’d always wanted to ride the Granada-Dakar Rally (formerly the Paris-Dakar Rally), 5000 miles of the most demanding off-road race in the world. My Cycle World connections got me a race entry and KTM America persuaded the parent company in Austria to chip in with a bike and parts support. I was in!

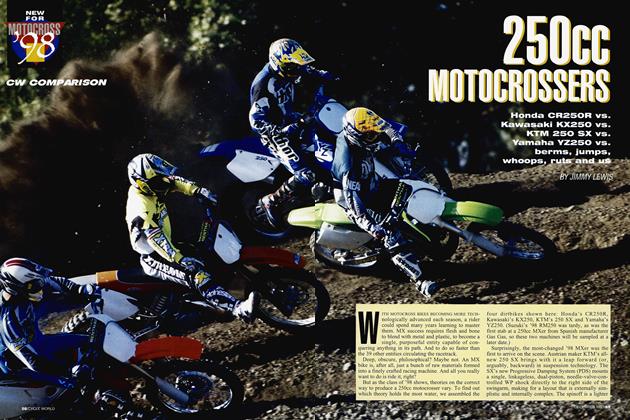

Jet-lagged from 14 hours of air travel, I arrived in Granada on the southern coast of Spain, and located the KTM team and my factory 660 rally bike, right off a special production line. Based on KTM’s 609cc four-stroke Single, it was a rolling gas station, 12 gallons in all, with auxiliary rear tanks, a fuel pump and seemingly miles of hose to keep the precious fluid moving to the carb. There was also the navigation equipment, consisting of a mapbook and computer-driven global positioning system.

Day 1s Prologue» Granada» Spain

After two full days of spinning wrenches, dispensing Loctite and applying safety wire, mechanic Eric Hjalmarson, on loan from KTM America, had my 660 ready for the start. I was another story. All of my enduro/motocross/ISDE/Baja experience would be needed for 17 days of pounding across six countries and the world’s biggest desert. As a rally rookie, I soaked up whatever advice I could get from veteran competitors and rally-goers. Like at the Prologue, a drag race to determine starting positions for the rally’s first stage. Just before I took off, Nevada Rally promoter Franco Acerbis approached; he advised me it would be best to go slow, that the Prologue’s finishing order would most likely be inverted the following day.

Never one for subtlety, I bogged the KTM off the line and slowly idled down the dirt dragstrip-to the distaste of the rabid Spanish crowd, 10,000 strong, which booed, whistled and jeered. I quickly pulled a wheelie and carried the front wheel for the length of the course, much to the delight of onlookers, now wild with applause. I still scored a terrible time, but at least I did it with style.

Day 21 Granada to Malaga, Spain

Franco’s plan was good. Rain had made a quagmire out of the motocross-like special test set up for spectators, but my early starting position worked. I was 10th-fastest. This was followed by a freeway stroll through the wine country of Spain, in the pouring rain, to Malaga. Here we loaded the rally’s 120 bikes, 106 cars and 70 big race trucks onto a ferry for the ride across the Mediterranean to Africa. The bunk in my cabin would be my last real bed during the rally.

Eric would follow the rally in various aircraft supplied by the organizers. Our sleeping bags, tent, extra clothes and toiletries had to fit in a bag the size of an airline carryon. Tools and a limited number of spare parts fit in a small box. We’d rely on KTM’s support truck for the rest.

Day 3i Vador to Oujda, Morocoo

I woke as we docked in Morocco, and unloaded the KTM just as the sun rose to light the Atlas mountains, where the first African special test would take place.

I made a stupid mistake without even knowing it when I forgot to switch money into durhams, the Moroccan currency. Mistake number two came as I blasted off with a full 12 gallons of fuel for a mere, 100-mile stage. At first, everything was going great; I was hanging in there with the likes of former World Motocross Champion Georges Jobe and previous Dakar Rally winner Edi Orioli. Then, I pushed a bit too hard, got into a slide across wet rocks and immediately realized why most of the riders had drained their rear tanks. The extra 30 pounds of fuel transformed

my stylish drift into a great low-side crash. Slightly scratched up, I arrived in Oujda in 22nd place. Not too bad, all things considered.

Day 4< Oujda to E Rachidia, Morocco

New Year’s Day. I greeted 1996 before first light, riding a 50-mile transfer stage to the day’s start. It was bone-chilling cold, though during the day the temperature would climb to 90-plus degrees. We were heading toward the Sahara Desert, but at first, the route was still mostly roads and adhering to the rally mapbook was critical.

High speeds and close calls were the order of the day. I came across Italian Fabrizio Meoni standing next to a ditch with his bike at the bottom, fork separated from the frame. The Dakar does not show forgiveness for even small mistakes. The tracks were rocky and fast, great terrain for the Yamaha and Cagiva twin-cylinder bikes to make time. Yamaha France’s Stephane Peterhansel, multi-time rally winner, pulled into the lead.

I made my goodwill gesture for the day by stopping for British rider John Deacon, who had broken a fuel line and run out of gas. What goes around comes around, though: Later, a gas-station attendant demanded that I pay in durhams, not francs, and Dutch rider Gerard Jimmink stepped up with enough funny money to pay my bill. Camaraderie runs high during the rally. It has to.

Day 5: Er Rachidia to Foum El Hassan Morocco

Today, we will cover 481 miles, nine hours in the saddle. Still, I feel good and the KTM is in top form-the only prob-

lem so far has been a tank bolt falling out, quickly fixed.

This was the first day we strayed from roads and did some free running, relying on our handlebar-mounted GPS setups. Linked to satellites, the GPS computer is programmed each day with the course’s waypoints. GPS plays an increasingly important role as we move into vast and open areas with fewer and fewer signs of life.

Danger reared its ugly head today, claiming two top riders. First was Spaniard Joan Roma, who overshot a tum and cartwheeled into a pile of rocks at what must have been a pretty high speed. Later, Jobe crashed into a ditch in a village, dislocating his shoulder. I remembered another bit of Franco Acerbis’ advice: The “real” Dakar does not start until Zouerat, he told me, ride steady, conserve energy, preserve the bike.

What was wearing on me now was the lack of a nice bed and a shower. I was able to budget enough space in my bag for a new T-shirt every other day and this was a clean-shirt day; even on a dirty body, it felt good. Because this was a marathon stage with no air support, I was contemplating sleeping on the ground before the KTM support truck showed up. Life is tough on the rally and the simple things became more and more important; even a sleeping bag seemed like a luxury.

Day 6s Foum El Hassan to Smara Morocco

Our last stage in Morocco. The rally was taking a constant toll. I passed riders whose engines sounded more like boxes full of loose nuts and bolts than powerplants. I was riding at about 60 percent of full speed and still moving up in the standings each day; results sheets made little difference to me, I just noticed more bikes stranded out on the course and fewer riders at each day’s finish.

The lesson for today was a deadly one. The dark side of Dakar revealed a death surrounded by controversy. A race truck had blown up and the driver burned to death in the ensuing fire. It was suspected the truck had run over a land mine. This jolted me like a blast of icy water: We were racing along the borders of recently warring nations; now I knew what those piles of dirt and stacks of rocks outlining corridors across the desert represented. According to my GPS, this wasn’t the straightest route, it certainly wasn’t the smoothest, either, but it had been swept for mines. Like the driver in the destroyed truck, I had strayed outside the corridors. I considered myself very lucky today.

Day 7 Smara, Morocco to Zouerat Mauritania

The highlight of the day was crossing the Mauritanian border. It was wickedly strange. All of a sudden, the route came to an area that was bulldozed with earthen walls. Atop these were machine-gun-toting Moroccan soldiers. Every mile or so for the next 20 were white U.N. jeeps or

tanks. Then another area with hundreds of troops in a slightly different color of fatigue, the Mauritanian forces. We had just passed through a no-man’s land, a fluctuating border between unfriendly countries. Later, talking to a French officer serving with the U.N., I got an indication of the power of the Dakar. “What you just did

today,” he said, “crossing that border and bringing all these people and equipment across, would take us six months. Your rally did it in a matter of hours.”

Now the course turned barren. There were times we’d come out of a set of mountains and the only feature as far as you could see was the curvature of the Earth with heat rising off the ground. Twenty minutes later, a glance behind would find the mountains melting into the horizon. Some time later, the mirage in front turns into a range of hills that takes another 20 minutes to reach at 80 miles per hour. Why not 100 or 110 mph, speeds the KTM 660 is easily capable of? I remember Franco’s advice-and just imagine the quality of gas you get in remote parts of Africa.

In fact, fuel played a major role in the leader board of the Dakar. Peterhansel got a load of what he and others thought was diesel at a remote gas stop. His bike coughed and sputtered, costing him his 20-minute lead, and then some. Disappointed, with winning his only goal, he said, “I raced 110 percent to get the lead that I had, and to lose it because of something like this is not right.” His protest was rejected, as 10 other riders took the same gas and had no problems. In disgust, Peterhansel abandoned the race.

He was not the only one. Wild man Heintz Kinigadner dropped out after cooking his works KTM in an effort to keep up with Peterhansel’s Yamaha Twin. When I passed his bike, it was sitting above a puddle of oil in a soft sandy valley, Heintz already in a helicopter on the way to the bivouac. French rider Thierry Magnaldi, running in the top three, was dealt disaster in a high-speed crash that cost him more than two hours, dropping him off the leader board.

The winner of the day was Belgarda Yamaha’s Italian rally star and three-time Dakar winner Orioli. He went from fourth to first by taking it easy, and was sitting pretty with a 41-minute advantage over Spaniard Jordi Acarons. Franco was right, the real Dakar would start at Zouerat.

The first night’s bivouac in Mauritania showed the true meaning of Third World. The country’s inhabitants are severely depressed financially, and even rally trash is a Christmas feast to them. Like most, we had a visitor to our little work area. We called him Michael, as in Jackson, because he wore a single glove, possibly a treasure from a past Dakar. In return for our extra food, he guarded our area from the other kids who would snoop a bit too close. He never spoke, just pointed to a spare can of com or carton of milk before moving on to adopt another rider for possibly an even better reward.

Our sentry gone, we had to literally stand guard over our things. The military lookouts, underpowered and armed with only whistles, ran short of breath chasing herds of children that seemingly came out of the sand, hiding in the shadows of tents and reaching inside for tools, loose wallets or food. I slept lightly in Mauritania.

That night our support truck never showed up. It was stuck out in the dunes along with 20 or so others. Eric and I arose at 3 a.m. to re-assemble our bike with a dirty air filter and a broken tank bracket, zip ties pulling extra duty.

Day 8: Zouerat Ma~irit ania to Atar,

Panic attack! My bike dies on the way to the start, victim of an electrical glitch. Could our pre-dawn assembly have been a bit half-ass? The British rider 1 helped in Morocco gives me a push back to the bivouac, where Eric and I trace the problem to a faulty handlebar switch. A quick dabbing with contact cleaner and Eric’s treasured clean Tshirt puts things right, and I make the start with time to spare, nerves only slightly worse for wear.

We had been warned about the sand dunes leading to Atar, supposedly the worst of the rally. Going in, I was apprehensive, but as I conquered more and more sand I was beginning to like this. It was like snowboarding: carving smooth lines, staying out of soft spots and avoiding the steep falls was the game. By now, Dutch ISDE ace Gerard Jimmink, my savior at the Moroccan gas stop, had become my riding partner. He trailed, content to let me navigate; in return, I had someone with me if help was needed. We made up a lot of time in the dunes-until I rudely discovered quicksand, that is.

At about 30 mph, I hit a patch and instantly sunk to the fenders, doing a creditable Superman routine over the handlebar as the bike brick-walled to a stop. I jumped up to warn Gerard, but he rode up right next to my bike without sinking. I had compressed the sand and it was hard now. We dug the bike out and fetched my jettisoned numberplate/windscreen, only to realize the GPS antenna was broken. I stuffed the parts inside my jacket and Gerard led the way to the finish.

Despite the quicksand crash, I’m overjoyed to find myself in ninth place. Top 10 in the Dakar! Yes!

Back at the camp, our truck finally shows up, but it’s been two days since the drivers last slept-and I thought riding was tough. Eric, thank God,, manages to do two days’ work in a few hours despite 100-degree temperatures.

Day 9: Ltar Mauritania to Zouerat,

For me, the loop back through Zouerat was not to be. The first sign of trouble came before breakfast when I had to vomit. I forced some food down, but I knew something was wrong.

Matters weren’t helped when, despite full fuel tanks, my bike sputtered to a stop early on, knee-capped by a plugged fuel pump. I was able to transfer gas by hose, bypassing the pump, and only lost about 20 minutes, but as the day wore on I was getting sicker and sicker. Somehow, I made it through the worst rocks and softest sand I had ever seen to arrive at the first gas stop, where I parked the bike, crawled under a truck and promptly barfed my guts out.

Doctors at the check examined my discharge (great job, eh?), handed me a bottle of water, which holds the value of gold in the Sahara, and told me to drink slowly, that I was dehydrated. I took a few sips, felt suddenly queasy and repeated my upchucking performance of 10 minutes previous. Doctors responded with two small white pills and a, “You’ll be okay in 45 minutes.”

I was not. An hour and two more bottles of precious water later, my body was now flushing itself through other orifices. Increasingly concerned, the doctors insisted on plumbing me for an IV drip and getting me back to camp. They loaded me semi-conscious into a helicopter, my faithful KTM left to the ravages of the recovery truck. At the bivouac’s rubber insta-hospital, I was handed some yellow pills and led off to my tent.

A day later, with the exchange of way too much money, Eric and I nabbed a plane ride out of Africa and back to Paris-the rally will deliver you back to the bivouac, but getting home from there is your responsibility. By the time I got back to the Cycle World offices, the Dakar was in its last five days. Every morning the fax machine cruelly taunted me with rally reports. I wasn’t there to see Orioli stretch his lead to an insurmountable 45 minutes and win Dakar for the fourth time. I wasn’t there to see Jimmink, my Dutch riding partner, cross the finish line in fourth place. I wasn’t there to celebrate on the beach at Dakar with the 50 riders who survived the rally.

Where I was, I had a hot shower every morning, a nice warm bed to sleep in, unlimited access to clean T-shirts, and sticky-fingered desert urchins weren’t trying to slither off with my money. At the time, it seemed like a pretty poor tradeoff.

It still does.