Betting men

TDC

Kevin Cameron

JUST A FEW YEARS AGO, WHEN WAYNE Rainey was ready to leave for Europe and grand prix roadracing, fellowracer Mike Baldwin said privately that he believed Wayne had a major quality that would ensure his success “Over There.” Just what that quality was, he didn’t explain.

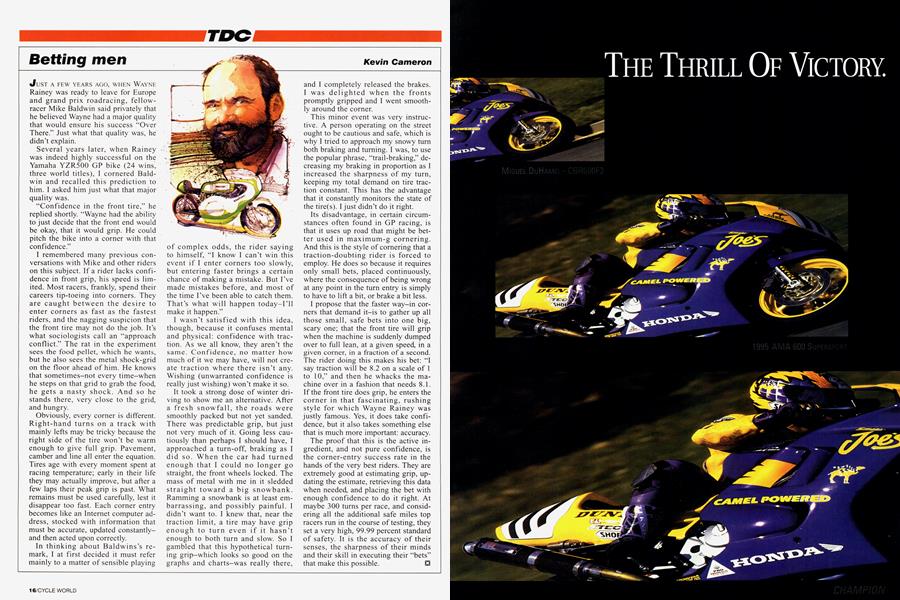

Several years later, when Rainey was indeed highly successful on the Yamaha YZR500 GP bike (24 wins, three world titles), I cornered Baldwin and recalled this prediction to him. I asked him just what that major quality was.

“Confidence in the front tire,” he replied shortly. “Wayne had the ability to just decide that the front end would be okay, that it would grip. He could pitch the bike into a corner with that confidence.”

I remembered many previous conversations with Mike and other riders on this subject. If a rider lacks confidence in front grip, his speed is limited. Most racers, frankly, spend their careers tip-toeing into corners. They are caught between the desire to enter corners as fast as the fastest riders, and the nagging suspicion that the front tire may not do the job. It’s what sociologists call an “approach conflict.” The rat in the experiment sees the food pellet, which he wants, but he also sees the metal shock-grid on the floor ahead of him. He knows that sometimes-not every time-when he steps on that grid to grab the food, he gets a nasty shock. And so he stands there, very close to the grid, and hungry.

Obviously, every corner is different. Right-hand turns on a track with mainly lefts may be tricky because the right side of the tire won’t be warm enough to give full grip. Pavement, camber and line all enter the equation. Tires age with every moment spent at racing temperature; early in their life they may actually improve, but after a few laps their peak grip is past. What remains must be used carefully, lest it disappear too fast. Each corner entry becomes like an Internet computer address, stocked with information that must be accurate, updated constantlyand then acted upon correctly.

In thinking about Baldwins’s remark, I at first decided it must refer mainly to a matter of sensible playing of complex odds, the rider saying to himself, “I know I can’t win this event if I enter corners too slowly, but entering faster brings a certain chance of making a mistake. But I’ve made mistakes before, and most of the time I’ve been able to catch them. That’s what will happen today-I’ll make it happen.”

I wasn’t satisfied with this idea, though, because it confuses mental and physical: confidence with traction. As we all know, they aren’t the same. Confidence, no matter how much of it we may have, will not create traction where there isn’t any. Wishing (unwarranted confidence is really just wishing) won’t make it so.

It took a strong dose of winter driving to show me an alternative. After a fresh snowfall, the roads were smoothly packed but not yet sanded. There was predictable grip, but just not very much of it. Going less cautiously than perhaps I should have, I approached a turn-off, braking as I did so. When the car had turned enough that I could no longer go straight, the front wheels locked. The mass of metal with me in it sledded straight toward a big snowbank. Ramming a snowbank is at least embarrassing, and possibly painful. I didn’t want to. I knew that, near the traction limit, a tire may have grip enough to turn even if it hasn’t enough to both turn and slow. So I gambled that this hypothetical turning grip-which looks so good on the graphs and charts-was really there,

and I completely released the brakes. I was delighted when the fronts promptly gripped and I went smoothly around the corner.

This minor event was very instructive. A person operating on the street ought to be cautious and safe, which is why I tried to approach my snowy turn both braking and turning. I was, to use the popular phrase, “trail-braking,” decreasing my braking in proportion as I increased the sharpness of my turn, keeping my total demand on tire traction constant. This has the advantage that it constantly monitors the state of the tire(s). I just didn’t do it right.

Its disadvantage, in certain circumstances often found in GP racing, is that it uses up road that might be better used in maximum-g cornering. And this is the style of cornering that a traction-doubting rider is forced to employ. He does so because it requires only small bets, placed continuously, where the consequence of being wrong at any point in the turn entry is simply to have to lift a bit, or brake a bit less.

I propose that the faster way-in corners that demand it-is to gather up all those small, safe bets into one big, scary one; that the front tire will grip when the machine is suddenly dumped over to full lean, at a given speed, in a given corner, in a fraction of a second. The rider doing this makes his bet: “I say traction will be 8.2 on a scale of 1 to 10,” and then he whacks the machine over in a fashion that needs 8.1. If the front tire does grip, he enters the corner in that fascinating, rushing style for which Wayne Rainey was justly famous. Yes, it does take confidence, but it also takes something else that is much more important: accuracy.

The proof that this is the active ingredient, and not pure confidence, is the corner-entry success rate in the hands of the very best riders. They are extremely good at estimating grip, updating the estimate, retrieving this data when needed, and placing the bet with enough confidence to do it right. At maybe 300 turns per race, and considering all the additional safe miles top racers run in the course of testing, they set a very high, 99.99 percent standard of safety. It is the accuracy of their senses, the sharpness of their minds and their skill in executing their “bets” that make this possible.