The Iron Man

UP FRONT

David Edwards

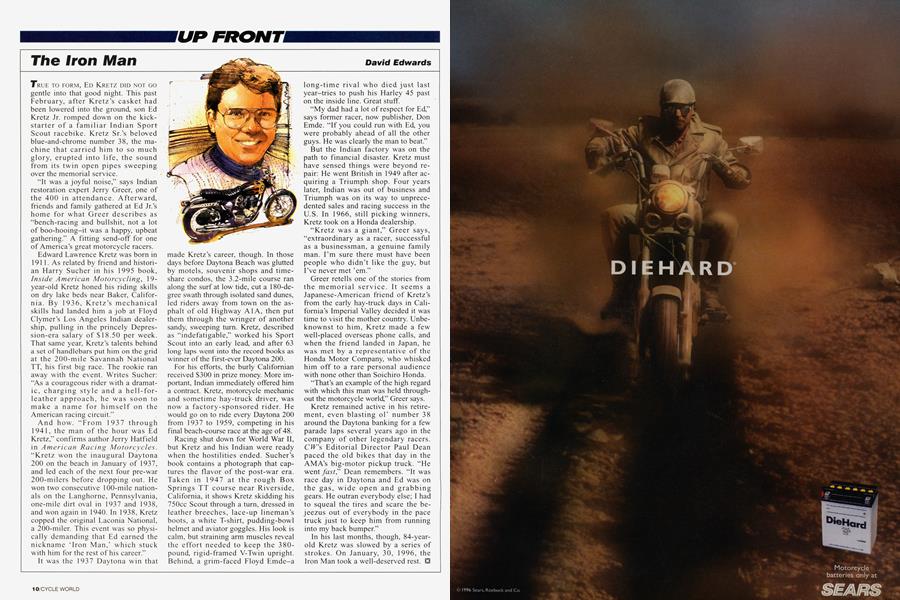

TRUE TO FORM, ED KRETZ DID NOT GO gentle into that good night. This past February, after Kretz’s casket had been lowered into the ground, son Ed Kretz Jr. romped down on the kickstarter of a familiar Indian Sport Scout racebike. Kretz Sr.’s beloved blue-and-chrome number 38, the machine that carried him to so much glory, erupted into life, the sound from its twin open pipes sweeping over the memorial service.

“It was a joyful noise,” says Indian restoration expert Jerry Greer, pne of the 400 in attendance. Afterward, friends and family gathered at Ed Jr.’s home for what Greer describes as “bench-racing and bullshit, not a lot of boo-hooing-it was a happy, upbeat gathering.” A fitting send-off for one of America’s great motorcycle racers.

Edward Lawrence Kretz was born in 1911. As related by friend and historian Harry Sucher in his 1995 book, Inside American Motorcycling, 19year-old Kretz honed his riding skills on dry lake beds near Baker, California. By 1936, Kretz’s mechanical skills had landed him a job at Floyd Clymer’s Los Angeles Indian dealership, pulling in the princely Depression-era salary of $18.50 per week. That same year, Kretz’s talents behind a set of handlebars put him on the grid at the 200-mile Savannah National TT, his first big race. The rookie ran away with the event. Writes Sucher: “As a courageous rider with a dramatic, charging style and a hell-forleather approach, he was soon to make a name for himself on the American racing circuit.”

And how. “From 1937 through 1941, the man of the hour was Ed Kretz,” confirms author Jerry Hatfield in American Racing Motorcycles. “Kretz won the inaugural Daytona 200 on the beach in January of 1937, and led each of the next four pre-war 200-milers before dropping out. He won two consecutive 100-mile nationals on the Langhorne, Pennsylvania, one-mile dirt oval in 1937 and 1938, and won again in 1940. In 1938, Kretz copped the original Laconia National, a 200-miler. This event was so physically demanding that Ed earned the nickname ‘Iron Man,’ which stuck with him for the rest of his career.”

It was the 1937 Daytona win that made Kretz’s career, though. In those days before Daytona Beach was glutted by motels, souvenir shops and timeshare condos, the 3.2-mile course ran along the surf at low tide, cut a 180-degree swath through isolated sand dunes, led riders away from town on the asphalt of old Highway Al A, then put them through the wringer of another sandy, sweeping turn. Kretz, described as “indefatigable,” worked his Sport Scout into an early lead, and after 63 long laps went into the record books as winner of the first-ever Daytona 200.

For his efforts, the burly Californian received $300 in prize money. More important, Indian immediately offered him a contract. Kretz, motorcycle mechanic and sometime hay-truck driver, was now a factory-sponsored rider. He would go on to ride every Daytona 200 from 1937 to 1959, competing in his final beach-course race at the age of 48.

Racing shut down for World War II, but Kretz and his Indian were ready when the hostilities ended. Sucher’s book contains a photograph that captures the flavor of the post-war era. Taken in 1947 at the rough Box Springs TT course near Riverside, California, it shows Kretz skidding his 750cc Scout through a turn, dressed in leather breeches, lace-up lineman’s boots, a white T-shirt, pudding-bowl helmet and aviator goggles. His look is calm, but straining arm muscles reveal the effort needed to keep the 380pound, rigid-framed V-Twin upright. Behind, a grim-faced Floyd Emde-a long-time rival who died just last year-tries to push his Harley 45 past on the inside line. Great stuff.

“My dad had a lot of respect for Ed,” says former racer, now publisher, Don Emde. “If you could run with Ed, you were probably ahead of all the other guys. He was clearly the man to beat.”

But the Indian factory was on the path to financial disaster. Kretz must have sensed things were beyond repair: He went British in 1949 after acquiring a Triumph shop. Four years later, Indian was out of business and Triumph was on its way to unprecedented sales and racing success in the U.S. In 1966, still picking winners, Kretz took on a Honda dealership.

“Kretz was a giant,” Greer says, “extraordinary as a racer, successful as a businessman, a genuine family man. I’m sure there must have been people who didn’t like the guy, but I’ve never met ’em.”

Greer retells one of the stories from the memorial service. It seems a Japanese-American friend of Kretz’s from the early hay-truck days in California’s Imperial Valley decided it was time to visit the mother country. Unbeknownst to him, Kretz made a few well-placed overseas phone calls, and when the friend landed in Japan, he was met by a representative of the Honda Motor Company, who whisked him off to a rare personal audience with none other than Soichiro Honda.

“That’s an example of the high regard with which this man was held throughout the motorcycle world,” Greer says.

Kretz remained active in his retirement, even blasting ol’ number 38 around the Daytona banking for a few parade laps several years ago in the company of other legendary racers. CW's Editorial Director Paul Dean paced the old bikes that day in the AMA’s big-motor pickup truck. “He went fast,” Dean remembers. “It was race day in Daytona and Ed was on the gas, wide open and grabbing gears. He outran everybody else; I had to squeal the tires and scare the bejeezus out of everybody in the pace truck just to keep him from running into my back bumper.”

In his last months, though, 84-yearold Kretz was slowed by a series of strokes. On January, 30, 1996, the Iron Man took a well-deserved rest. U