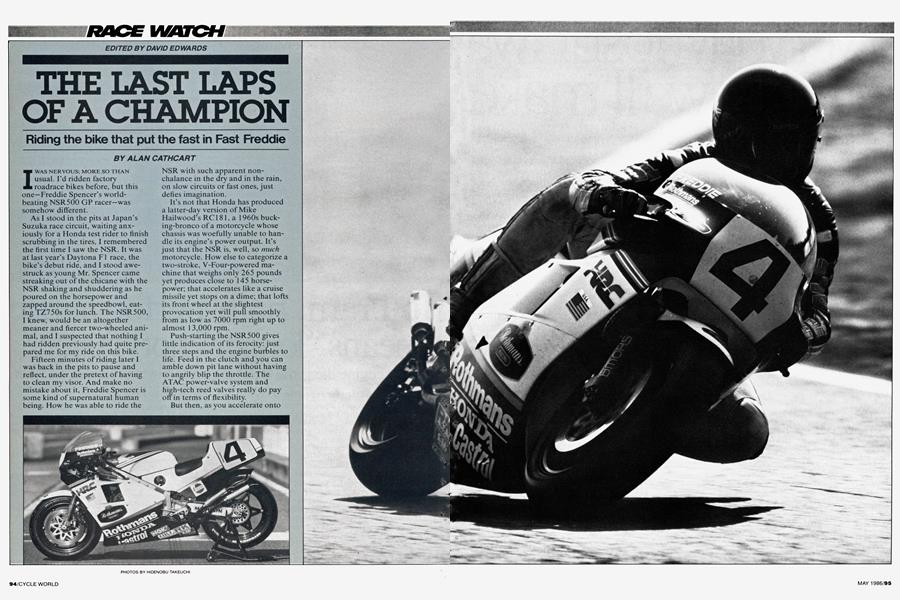

THE LAST LAPS OF A CHAMPION

RACE WATCH

DAVID EDWARDS

Riding the bike that put the fast in Fast Freddie

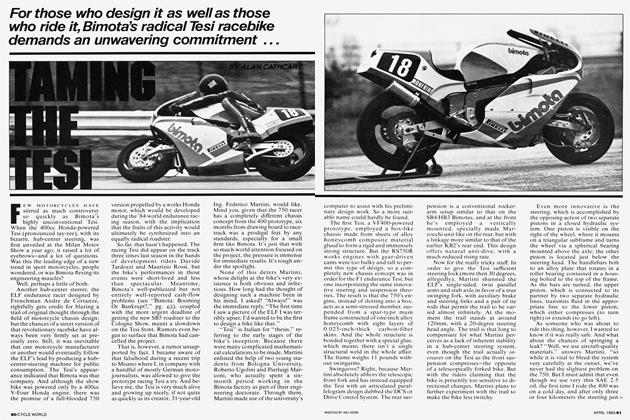

ALAN CATHCART

I WAS NERVOUS; MORE SO THAN usual. I'd ridden factory roadrace bikes before, but this one—Freddie Spencer's worldbeating NSR500 GP racer—was somehow different.

As I stood in the pits at Japan’s Suzuka race circuit, waiting anxiously for a Honda test rider to finish scrubbing in the tires, I remembered the first time I saw the NSR. It was at last year’s Daytona F1 race, the bike’s debut ride, and I stood awestruck as young Mr. Spencer came streaking out of the chicane with the NSR shaking and shuddering as he poured on the horsepower and zapped around the speedbowl, eating TZ750s for lunch. The NSR500, I knew, would be an altogether meaner and fiercer two-wheeled animal, and I suspected that nothing I had ridden previously had quite prepared me for my ride on this bike.

Fifteen minutes of riding later I was back in the pits to pause and reflect, under the pretext of having to clean my visor. And make no mistake about it, Freddie Spencer is some kind of supernatural human being. How he was able to ride the NSR with such apparent nonchalance in the dry and in the rain, on slow circuits or fast ones, just defies imagination.

It’s not that Honda has produced a latter-day version of Mike Hailwood’s RC 181, a 1960s bucking-bronco of a motorcycle whose chassis was woefully unable to handle its engine’s power output. It’s just that the NSR is, well, so much motorcycle. How else to categorize a two-stroke, V-Four-powered machine that weighs only 265 pounds yet produces close to 145 horsepower; that accelerates like a cruise missile yet stops on a dime; that lofts its front wheel at the slightest provocation yet will pull smoothly from as low as 7000 rpm right up to almost 13,000 rpm.

Push-starting the NSR500 gives little indication of its ferocity; just three steps and the engine burbles to life. Feed in the clutch and you can amble down pit lane without having to angrily blip the throttle. The ATAC power-valve system and high-tech reed valves really do pay off in terms of flexibility.

But then, as you accelerate onto the track and yank the cables on the two twin-choke, 34mm Keihin carburetors, everything suddenly is compressed into fractions of normal time—as if someone has punched the video you’re watching into fast-forward. What’s really happened is that the tach needle has reached 9500 or thereabouts and the engine has instantly taken off into a superpowerband where the likes of Freddie Spencer prefer to operate, especially if they’re after world roadracing titles.

In spite of having to contend with the stresses that such horsepower creates, the NSR’s lightweight aluminum frame does an admirable of job. There was one section of the Suzuka track that it didn’t like, however, a fast right-hander just after the chicane. There’s a large bump there that would send the 500 into a dreadful dither, wobbling and shaking its way down the track if I kept the power on hard. I found it better to ease off before the bump, then cut in tight and miss it. That resulted in more speed at the end of the straightaway, not to mention a reduced heart rate on my part.

Another characteristic that I never got used to was the front wheel’s propensity for popping massive wheelies while accelerating out of slow corners, especially Suzuka’s uphill hairpin. I tried taking it in second gear, but there was no way to stay in the fat part of the powerband. So it was down to first while I resigned myself to doing a feeble imitation of a mono-wheeling Spencer. It almost got to be fun— until, that is, I tried the maneuver while coming out of the corner before the back straight. I indiscreetly whacked open the throttle, sending the engine into its 9500-rpm power surge, the front wheel way into the air, and the priceless pride-and-joy of Honda Racing Corporation towards the edge of the track. It was only by fluke that the NSR and I didn’t end up in the grass. Pass the oxygen bottle, please.

Throttle control is the key to riding the NSR500. Because I was the last person to ride the NSR before it either got scrapped or put on display (the latter, hopefully, although Honda officials weren’t saying), I was allowed more time on the bike than usual. At the end of 30 laps, I was finally beginning to make friends with the beast, even if it was only on the very last lap that I managed to screw up enough nerve to get flat-out in top gear along the back straight—and even then, I eased up early for the following left-hand sweeper. Still, during those 30 laps, I went from wondering how I was ever going to cut respectable lap times (while staying in one piece) to looking for ways to use the bike’s power and torque to my advantage. Rather than using lots of revs, as you must do on the NSR’s three-cylinder precursor, the NS500, it’s much better to shift up a gear and then pour on the power when needed by opening the throttle—not snapping it open, mind you, which is a good way to land on your ear, but smoothly feeding in the extra revs. The NSR responds well to this type of treatment. It’s a bit like cantering a thoroughbred stallion, then switching to full gallop: All that it takes is finesse.

In 1985, Freddie Spencer was able to finesse an almost unbeatable performance out of the NSR500. With one more year of refinement to the bike and with Spencer unbothered by the chore of having to defend his 250cc title, the 1986 grand prix season could very well turn out to be six months of seeing who manages to finish in second place behind Freddie Spencer and his incredible motorcycle.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue