Dressing up

AT LARGE

DESPITE THE STICKY HEAT. WHEN I ARrived for my check-out in the North American AT-6 “Texan” advanced trainer, I was wearing my Air Force Nomex flight suit. So was my flight instructor, a Royal New Zealand Air Force wing commander. We sweated together. Nobody said anything about the hot suits. They were de rigueur for flying a beast like the T-6.

The day I climbed into the Ralt RT-1 Formula Atlantic car at Sears Point for testing, I wore Nomex, too. Head to foot. The weather was hot, and so was I. Nobody said anything about the Nomex; It was de rigueur.

From the first day I roadraced motorcycles, I wore the best leathers I could get. And predictably, at the track, nobody said anything about them: They, too, were de rigueur.

But the day in 1967 I ventured out onto the street with those black-andred Webco leathers, I knew that the standards that applied to flying, driving race cars and riding race bikes didn’t apply Outside. There, if you didn’t fit some kind of vague, stereotypical image of what a bike rider should wear, you could expect ridicule—not just from ignorant non-riders, but even from motorcyclists who ought to have known better.

That day, I was breaking in some fresh Dunlop KRs and new pistons by taking a long, fast loop through the Gold Country of California. I wore my leathers because I knew I would be pushing some limits—not at track speeds, maybe, but close. Too close for jeans and a nylon jacket. The leathers were uncomfortable. But as the day wore on, I was glad to have them, as the rough backcountry two-lane warmed and I pushed a bit more on each turn.

By midday I was famished, and stopped at a famous tavern in the old gold town of Coloma to cool down and fill up. The scene that ensued when I walked in, unzipping my leathers and pulling off my Bell 500TX, was a classic, straight from the worst Westerns. I stood in the foyer of the dark little place and blinked, suddenly aware that all the eyeballs in the tavern were locked on me, aware, too, that the silence was deafening. After a moment, somebody in the gloom laughed, and then it was echoed. That was the moment I realized I was going to be at war with

some basic American values for a long, long time.

I was right. I found out how right when I first wore Andy Goldfine’s superb Aerostich riding suit last year. As high-tech a garment as my Webco leathers were low-tech, the Aerostich looked great and worked better. And the best thing, I thought, was that it was a do-everything suit; a reasonable rainsuit, fine to wear over Brooks Brothers, or a good choice for a warm afternoon’s ride, with only tennis shorts and a polo shirt under its protective Gore-Tex and Cordura.

But it was red—scarlet, really, so scarlet that you could not fail to notice it. Pondering it after I unpacked it, I decided that not only was the red attractive, it was also great from a safety standpoint, at least if the theory of conspicuity has any merit. As I expected, my first ride in the Aerostich turned a lot of heads. What I hadn’t expected, all these years into the new age of motorcycling, was that the most stupid comment about the suit would come not from a nonrider, but from one of us.

My destination that day was the retail outlet of a national motorcycleparts supply outfit headquartered in the D.C. area. I parked the bike, strolled into the storefront office, and smack into the same ignorance that pervaded that Coloma tavern almost 20 years before. The guy behind the counter watched me enter his store, then smirked.

“What’s wrong, pal? You cold?” He waved his pen at the suit. I didn’t answer, it being better than 80 degrees outside. No answer was necessary, and none—short of re-educating the gent—was really up to the man’s

colossal ignorance.

There is an obvious reason why riding gear for streetbikes is so stylesensitive: Riding a streetbike is itself a matter largely of style. In my na‘ iveté back in ’67, I was amazed that anyone could misconstrue the reasoning behind wearing maxmium protective gear aboard a powerful sportbike, but I learned quickly to expect swinish remarks from yahoos whenever I ventured onto the highway clad in anything other than jeans, Dingo boots and maybe a disreputable leather jacket.

All of this would be of only social or personal interest were it not for the effect such ignorance has on what we can wear to protect ourselves. Goldfine’s suit is a long way from perfect, but that it exists at all is a major triumph, given the pervasive bigotry that has afflicted American motorcycling. This bigotry manifests itself both as public ridicule of “different” apparel and our consequent reluctance to explore such apparel.

This translates to motorcyclists wearing subdued colors in garments tailored to look as much like “normal” street clothing as possible. In fact, of course, riding gear optimized to meet the needs of a rider, as opposed to those of a pedestrian, inevitably looks nothing at all like something found in a department store. Yet motorcycle apparel manufacturers still are forced to offer a lot of stuff that is at best only a bad compromise between the two fashions. The prejudices inherent in this are the more odious since they emanate from a people that declares itself to be the freest-thinking on earth. We talk a lot about individual freedom of expression—especially as motorcyclists— but when we practice it, we run headlong into barriers most of us are simply not up to surmounting.

Most American riders today have the political and economic freedom for any kind of self-expression they wish. What they lack—still—is the social freedom for that self-expression. You don’t get that freedom by talking about it. You get it by exercising it, by ignoring the yahoos in the tavern,. smiling at the waitress, sitting down in the booth and ordering your food. Do that long enough, and one day the yahoos are wearing what you wear.

-Steven L. Thompson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialThe First Time Is the Worst Time

May 1986 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

May 1986 -

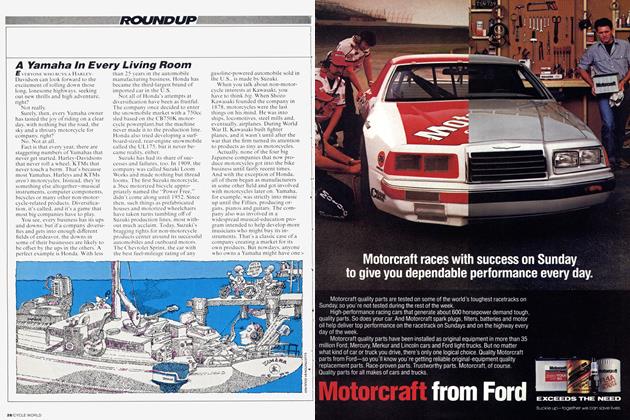

Roundup

RoundupA Yamaha In Every Living Room

May 1986 -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

May 1986 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

May 1986 By Alan Cathcart -

Features

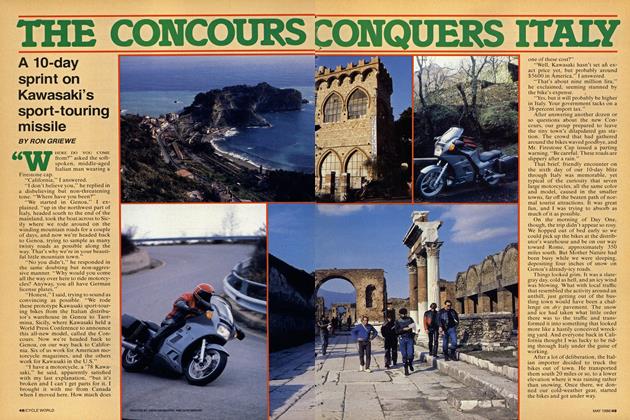

FeaturesThe Concours Conquers Italy

May 1986 By Ron Griewe