Smokin'!

IN 1969, HONDA'S CB750 WAS BIG NEWS, BUT KAWASAKI'S H1 MACH III WAS THE KING OF QUICK

KEVIN CAMERON

THE PHRASE “MORE BANG FOR THE BUCK” WAS coined for the Atom Bomb, but applies much more agreeably to Kawasaki’s sensational H1 three-cylinder, two-stroke street machine. Selling at $999 when it hit showroom floors in 1969, the H1 was the “equalizer” that thousands of riders of smaller Japanese machines had been waiting for.

Boston’s Arlington Motor Sports, where I was a partner at the time, was open late most evenings. Our HI customers would come crowding in from the dark evening, their faces alight with excitement, like carrier pilots returned from an air strike, describing with words and gestures the local bike kings they had just toppled-Harleys, Beezers, Trumpets. All were cut down with ease by these young men on their smoking Triples.

And best of all, these new bikes were stock, machines that worked without cajoling and veteran expertise. Anyone who put in $1000 and three gallons of gas could become a hero, able to blow down those swaggering big-bike tough guys.

The technique for launching an HI was expertly demonstrated by official Kawasaki service personnel, as it was an important sales tool. Stand on the pavement astride the running machine, your weight on your feet like a motocrosser. Bring the revs up and drop the clutch, setting the tire spinning and smoking, then sit down, holding the revs at peak torque, and rocket away.

Of course, not all the smoke was from the tire. Kawasaki’s production two-strokes had pump-lubricated crankshafts like the factory racers of the 1960s. The throttle-controlled pumps were factory-set on what the Japanese technicians called “safety-side.” We joked about the setting marks on the oil-pump control quadrant; this one was “seizure,” the next was “normal,” and the factory setting was “mosquito control.” Simply resetting the pump to a leaner mark did away with most of the smoke, with no loss of reliability.

Previous two-strokes from other makers had been infamous for plug fouling, but Kawasaki fixed that by providing electronic ignitions that sent a sharp spike of voltage that jumped the plug gap before “leakage current” (meaning conduction down the black carbon all over the insulator) could stop it. On the HI, this created its own special problems. Start your new HI at night and, chances were, you’d see spooky blue corona discharge spiderwebbing all over the distributor side of the engine as the plentiful spark power poured out. We received a steady stream of service bulletins on how to keep the electricity inside the system and on its way to the strange-looking surface-gap sparkplugs-silicone wire, hi-voltage o-scope probe wire, updated distributors, finally no distributor at all.

The year before, we had all awaited the rumored Triple in eager speculation; one magazine said the engine would resemble the 1950s DKW Three, with two cylinders pointed up, one down. Others predicted three in a row-which it was. Nothing, however, prepared us for the music of the Hi’s exhaust. Three cylinders winding out and away make a wonderful sound, quite unlike the ding-y noise of a twostroke Single, or the monotonous buzz of a Twin. The Triple had a wild, brassy, resonant sound that stirred men’s souls.

There were negative qualities packaged with the positives. The HI gained a reputation for ill-handling that eclipsed even that of the legendary Vincent. In fairness to both Kawasaki and Vincent, high power is the sworn enemy of good handling. All manufacturers had to learn how to combine power and stability. Kawasaki, the hot-rod pioneer, took the lion’s share of the heat in the process.

Another enemy was rust, especially when water-loving polyglycol two-stroke oil was used. College men with no place to garage their bikes left them outdoors through the rainy, slushy winter. Water, iron and oxygen reacted to weld piston rings to cylinder walls, rollers and balls to raceways. In the spring, there was a mad rush of work orders, all saying, “Get running. Kickstart lever will not go down.” Other owners couldn’t be bothered to keep oil in the tank. Their bikes would come in on trailers, seized, their oil lines empty, their oil tanks suspiciously full. Others killed their bikes with outboard oil, motor oil or cooking oil—anything but real two-stroke oil.

We also had other customers who understood bikes, rode their Hls hard and fast-and got 50,000 miles from their original crankshafts. It was these enlightened riders who began the modem practice of suspension and tire upgrading, putting their bikes on Konis and Dunlops. Soon Kawasaki had to raise the pipes for more ground clearance. They called these jauntier smokestacks “Mosport pipes,” after the Canadian track where the Triple’s greatest rider, Yvon DuHamel, had won so many races.

Soon came the bigger, faster, more intense 1972 750 H2, a kind of HI on steroids, and almost immediately, Kawasaki’s definitive answer to the Honda CB750, the fourstroke 903cc Z-l. The Triples remained in production a while, but were detuned to ensure a future safe for fourstrokes. I left the retail business behind and moved to the countryside, but for years afterward, on summer nights I could hear the music of those Triples off in the distance after closing time. What had been a steady trade in Triple crankshaft rebuilding dwindled away to the occasional plaintive call to make one good one out of two bad ones. Still, parts and speed equipment for these bikes remain in production, for there has truly never been more bang for the buck. The machines slowly passed into classic status along with their riders, who, even today, command special respect from younger peers.

People say of them, “He used to ride Kawi Triples.” O

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

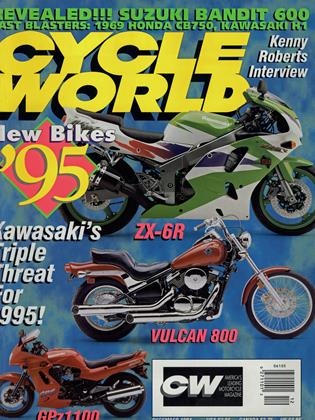

Up FrontThe Endless Ride

December 1994 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsSaving For A Vincent

December 1994 By Peter Egan -

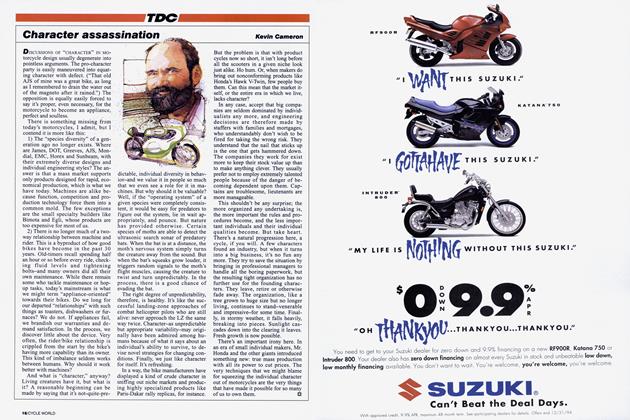

TDC

TDCCharacter Assassination

December 1994 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1994 -

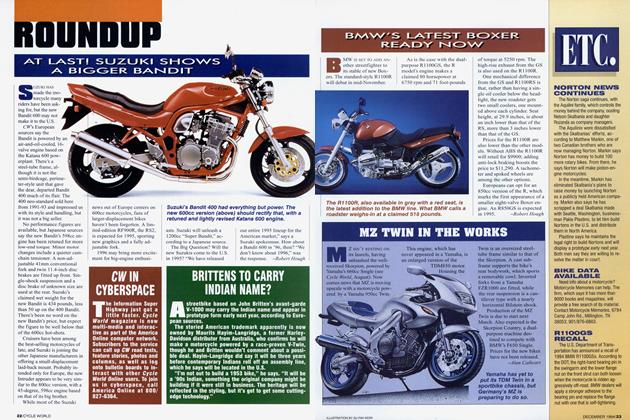

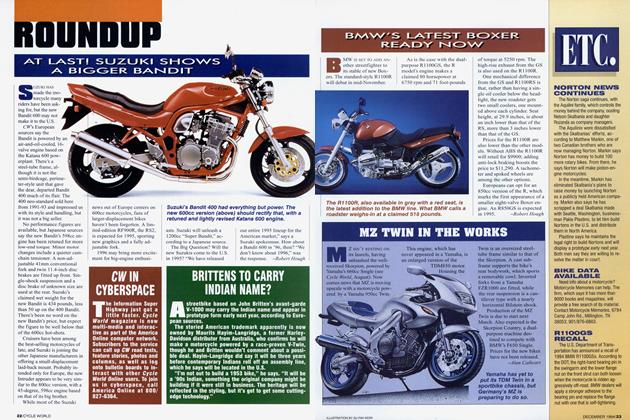

Roundup

RoundupAt Last! Suzuki Shows A Bigger Bandit

December 1994 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupCw In Cyberspace

December 1994