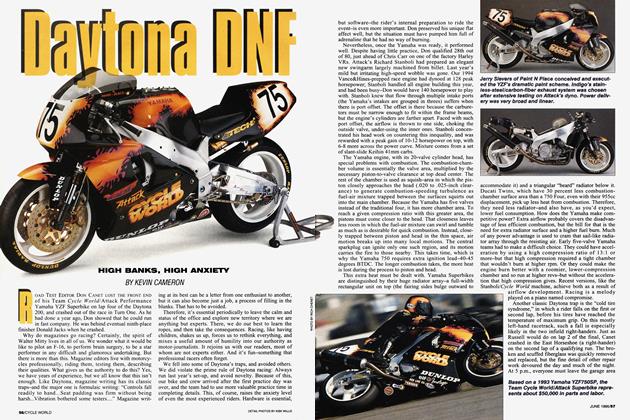

The Second Coming of Fast Freddie

RACE WATCH

ON HIS WAY UP OR ON HIS WAY OUT?

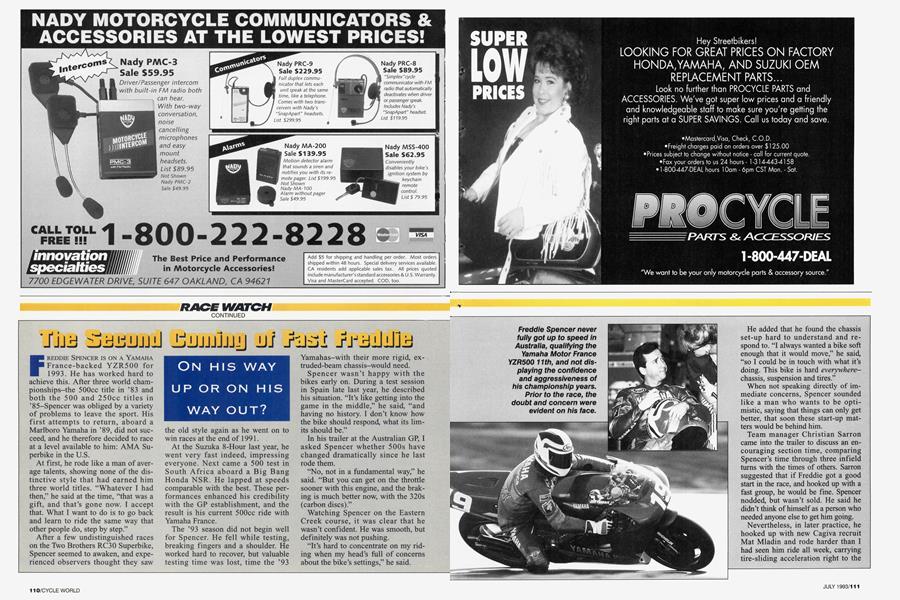

FREDDIE SPENCER IS ON A YAMAHA France-backed YZR500 for 1993. He has worked hard to achieve this. After three world championships-the 500cc title in ’83 and both the 500 and 250cc titles in ’85-Spencer was obliged by a variety of problems to leave the sport. His first attempts to return, aboard a Marlboro Yamaha in ’89, did not succeed, and he therefore decided to race at a level available to him: AMA Superbike in the U.S.

At first, he rode like a man of average talents, showing none of the distinctive style that had earned him three world titles. “Whatever I had then,” he said at the time, “that was a gift, and that’s gone now. I accept that. What I want to do is to go back and learn to ride the same way that other people do, step by step.”

After a few undistinguished races on the Two Brothers RC30 Superbike, Spencer seemed to awaken, and experienced observers thought they saw the old style again as he went on to win races at the end of 1991.

At the Suzuka 8-Hour last year, he went very fast indeed, impressing everyone. Next came a 500 test in South Africa aboard a Big Bang Honda NSR. He lapped at speeds comparable with the best. These performances enhanced his credibility with the GP establishment, and the result is his current 500cc ride with Yamaha France.

The ’93 season did not begin well for Spencer. He fell while testing, breaking fingers and a shoulder. He worked hard to recover, but valuable testing time was lost, time the ’93 Yamahas-with their more rigid, extruded-beam chassis-would need.

Spencer wasn’t happy with the bikes early on. During a test session in Spain late last year, he described his situation. “It’s like getting into the game in the middle,” he said, “and having no history. I don’t know how the bike should respond, what its limits should be.”

In his trailer at the Australian GP, I asked Spencer whether 500s have changed dramatically since he last rode them.

“No, not in a fundamental way,” he said. “But you can get on the throttle sooner with this engine, and the braking is much better now, with the 320s (carbon discs).”

Watching Spencer on the Eastern Creek course, it was clear that he wasn’t confident. He was smooth, but definitely was not pushing.

“It’s hard to concentrate on my riding when my head’s full of concerns about the bike’s settings,” he said.

He added that he found the chassis set-up hard to understand and respond to. “I always wanted a bike soft enough that it would move,” he said, “so I could be in touch with what it’s doing. This bike is hard everywherechassis, suspension and tires.”

When not speaking directly of immediate concerns, Spencer sounded like a man who wants to be optimistic, saying that things can only get better, that soon these start-up matters would be behind him.

Team manager Christian Sarron came into the trailer to discuss an encouraging section time, comparing Spencer’s time through three infield turns with the times of others. Sarron suggested that if Freddie got a good start in the race, and hooked up with a fast group, he would be fine. Spencer nodded, but wasn’t sold. He said he didn’t think of himself as a person who needed anyone else to get him going.

Nevertheless, in later practice, he hooked up with new Cagiva recruit Mat Mladin and rode harder than I had seen him ride all week, carrying tire-sliding acceleration right to the edge of the track. After passing Mladin, he looked back to see the distance he’d gained.

At Daytona, Dunlop’s Dave Watkins had described how the data systems now in use show how riders, unsure of grip, pulse the throttle once or twice before really getting on it as a traction diagnostic. I could hear Spencer doing this in practice. He was clearly not committing himself to the unknown.

Spencer’s team, headed by Serge Rosset (the man responsible for making a racebike out of the various ELF projects), was leaving final engine tuning for Sunday morning. Spencer noted that his speed-trap numbers were still down 5 to 6 mph. Someone noted that his section time had come within three-tenths of a second of the quickest times, but Spencer’s face still showed more concern than confidence. The track was bumpy, the bike hard-sprung and not working. Lots to learn: new bike, new team, new language, new era. And little time.

In the race, Spencer came around 12th on the first lap-not far from his qualifying position of 1 lth-and some distance behind 1991-92 250cc World Champion Luca Cadalora, on the second Team Roberts Yamaha. Cadalora is a fine rider, but not yet a 500 rider, for he still scribes the sweeping geometric lines used by 250s. By lap eight, Spencer was clearly catching Cadalora, but slowly, and it took until lap 13 to get close.

They then rode around together, lap after lap, until Spencer disappeared on lap 19. His bike had seized its waterpump in the fast left-hand Turn One. There was a lot of tire smoke, and Spencer smacked his head hard enough to render him unconscious. He remembers nothing.

He was determined to go on to Malaysia for the second grand prix, but the series’ doctors would not let him race there because of his remaining dizziness. He expects to be fit for the Japan GR

Whether he competes or not, it seems clear that Freddie Spencer’s return to GP racing will be very different than his first ventures there.

Kevin Cameron