History @ Speed

From CB900F to RC51, 20 years of Honda Superbikes

KEVIN CAMERON

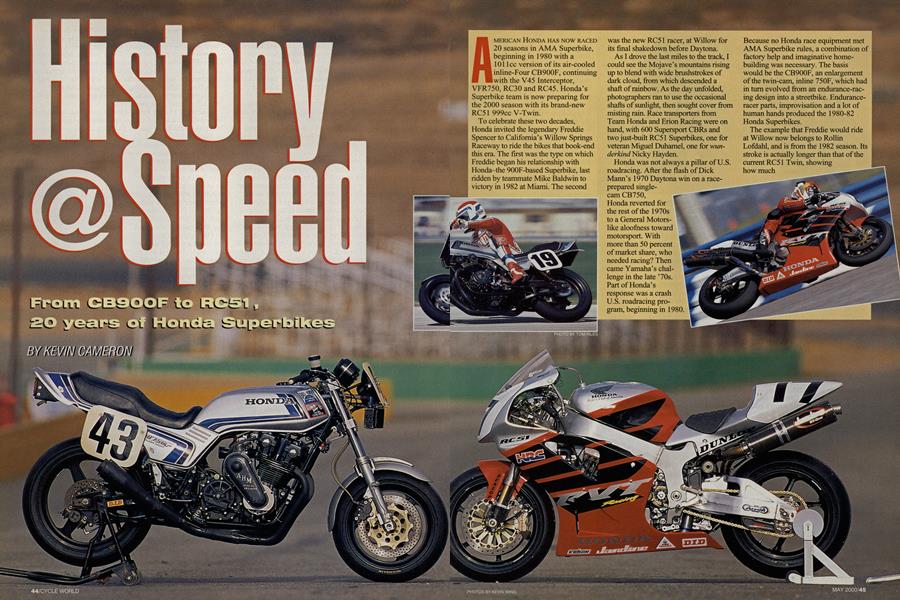

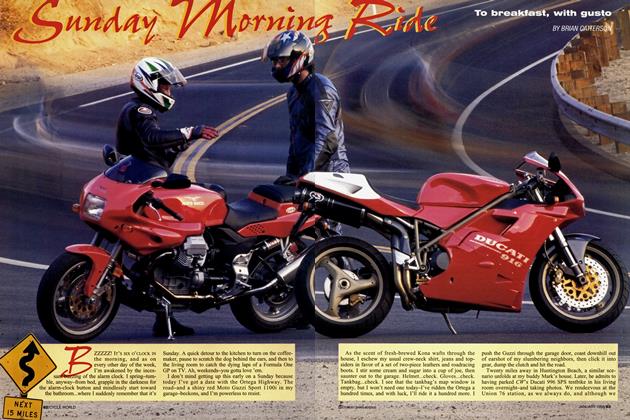

AMERICAN HONDA HAS NOW RACED 20 seasons in AMA Superbike, beginning in 1980 with a 1011cc version of its air-cooled inline-Four CB900F, continuing with the V45 Interceptor, VFR750, RC30 and RC45. Honda's Superbike team is now preparing for the 2000 season with its brand-new RC51 999cc V-Twin.

To celebrate these two decades,

Honda invited the legendary Freddie Spencer to California’s Willow Springs Raceway to ride the bikes that book-end this era. The first was the type on which Freddie began his relationship with Honda-the 900F-based Superbike, last ridden by teammate Mike Baldwin to victory in 1982 at Miami. The second

was the new RC51 racer, at Willow for its final shakedown before Daytona.

As I drove the last miles to the track, I could see the Mojave’s mountains rising up to blend with wide brushstrokes of dark cloud, from which descended a shaft of rainbow. As the day unfolded, photographers ran to use the occasional shafts of sunlight, then sought cover from misting rain. Race transporters from Team Honda and Erion Racing were on hand, with 600 Supersport CBRs and two just-built RC51 Superbikes, one for veteran Miguel Duhamel, one for Wunderkind Nicky Hayden.

Honda was not always a pillar of U.S. roadracing. After the flash of Dick Mann’s 1970 Daytona win on a raceprepared singlecam CB750,

Honda reverted for the rest of the 1970s to a General Motorslike aloofness toward motorsport. With more than 50 percent of market share, who needed racing? Then came Yamaha’s challenge in the late ’70s.

Part of Honda’s response was a crash U.S. roadracing program, beginning in 1980.

Because no Honda race equipment met AMA Superbike rules, a combination of factory help and imaginative homebuilding was necessary. The basis would be the CB900F, an enlargement of the twin-cam, inline 75 OF, which had in turn evolved from an endurance-racing design into a streetbike. Enduranceracer parts, improvisation and a lot of human hands produced the 1980-82 Honda Superbikes.

The example that Freddie would ride at Willow now belongs to Rollin Lofdahl, and is from the 1982 season. Its stroke is actually longer than that of the current RC51 Twin, showing how much

engine design has changed over two decades. Bore/stroke ratio of the 1982 bike is .99 (68.3 x 69.0mm), while that of the RC51 is 1.57 (100.0 x 63.6mm).

Where a weak point of that early Four was its chain camdrive, the cams of the new RC51 are actuated by geartrains. Continuing the comparison, the 900F racer is air-cooled and carbureted, while the 51 is liquid-cooled and fuel-injected. The 900 is also a classic “standard,” a naked bike, while the 51 is closely faired (and almost 2 inches narrower than the RC45 V-Four that preceded it).

The machines fielded by American Honda in 1980 combined parts from the endurance-racing program-the dry clutch and dry-sump oiling system, for example-with cylinder-head preparation from the U.S. side. Heads were sent out to all prominent airflow shops. Everything would be dynoed and the best components chosen. The professionally outrageous former racer Steve McLaughlin was made team manager; ex-Butler & Smith BMW engine builder Udo Gietl became his crew chief; and extensive fabrication was directed by the massively genial Todd Schuster. As legend has it, when Gietl proposed testing Del West titanium valves, McLaughlin grandly wrote an order for $12,000

worth. Everything was done with a flourish (to this day McLaughlin, no longer associated with Honda, arrives by limousine for business meetings in a white suit and Borsalino hat). A huge amount of work was accomplished, machines were built and raced, and Honda was back on the U.S. competition scene with a crew that knew its business.

Nothing this unconventional could long co-exist with responsible accounting practice. Ron Murakami replaced McLaughlin as team manager and set about making Honda racing sustainable. The weak RSC ignition was replaced by a reliable German-made Krober. When Freddie dragged this ignition on the ground at Laguna Seca, Gietl moved it to where you see it on this machine, safely above the gearbox on the right side, driven by a cog-belt. The formed-aluminum front fender bracket is one of many made by Schuster-he hand-fabbed the first one at Daytona. Once proven, trick, handbuilt parts like this were replaced by accelerating flows of series-produced hardware. The machines became maintainable, and mechanics ceased having to do engineering after midnight.

For the first go at Daytona, 1980, Mr. Aika, famed manager of Honda’s 1960s GP team, was present. Although he guaranteed the durability of the 1011 cc engines, the team soon found ways to break them. Can mild endurance cams win sprint races? No, and sprint cams with tall, pointed lobes break the best of camchains, even with light titanium valves. At Daytona 1981, all available fresh engines were wrecked by Tuesday p.m., and the crew spent Wednesday building new ones from parts.

Reliability is always made from broken parts, and in this rush program, there was no time to break them in secret. It all happened in broad daylight, just like the early U.S. space program.

For the 1983 season, the AMA cut Superbike displacement from 1025 to 750cc. Honda’s new V-Four 750 Interceptor was ready. Intended only as a homologation special estimated to have low sales prospects, this model stunned its creators by selling out on the strength of its excellent handling. Up to that time, bikes were sold on appearance and “numbers”-quarter-mile time and top speed. The Interceptor not only redefined the sports motorcycle, in 1984 it brought Honda its first Superbike title, with rider Fred Merkel. Merkel repeated in ’85 on the Interceptor, and again in ’86 on the new VFR750. Wayne Rainey and Bubba Shobert likewise took Superbike titles on VFRs in ’87 and ’88.

Meanwhile, Freddie Spencer would win the Daytona Superbike race four

times in a row, beginning in 1982. In 1985, he won all three classes at Daytona-the 200mile Superbike race, Formula 1 and Formula 2, then went on to win both the 250 and 500cc World Championships-something that has not been achieved since. They say that time is what keeps everything from happening at once, but Freddie rode as if time didn’t exist. For him, it did all happen at once. Of that season, Mike Baldwin (Freddie’s teammate in 198182, and himself a former GP racer) said, “If you didn’t see it, if you weren’t there to see him get off the 250 and go straight out and win the 500 race like it was the easiest thing in the world, you just wouldn’t know. He was brilliant.” For the 1990 season, new AMA Pro Competition Director Ron Zimmerman pushed through equipment rules allowing World Superbike-derived machines like Honda’s limited-production RC30 to run in AMA Superbike. Duhamel won the 1991 Daytona with one, but the RC30 never took a U.S. title.

In 1994, three years later than planned, the RC30’s replacement arrived in America-the RC45. This slow-developing machine would win

two AMA Superbike titles for Honda, in 1995 (Duhamel) and 1998 (Ben Bostrom). Today, all RC45 V-Fours have been retired, and both AMA and World Superbike teams will race only the new RC51 V-Twin. In early testing, the Twin set the quickest times at WSB practice in Australia (see “World Superbike Weapon” page 52). This move from four to two cylinders is a big step for Honda, whose name has been associated with four-cylinder racers ever since the first 250 Fours, 41 years ago.

Now my attention switched to the 1982 bike. Owner Lofdahl and a volunteer crew were trying to push-start it, and it was responding by dragging its back tire, chattering and popping. At length, it started and ran. The engine has Keihin CR carbs on it now, even though the bike still has period Qwik Silver stickers showing. It warmed up on a high, fluttery idle that Baldwin says was a CR characteristic. With the much bigger Qwik Silver carbs (good for a rumored extra 20 bhp), the bike had to be set up to “idle” at 3500. The reason for this was two-fold: First, high idle softens wheel hop on big four-strokes during deceleration. Second, the throttle gates on the Qwik Silvers had so much stiction that idle vacuum made the throttles stick shut, impossible to lift smoothly.

“Getting that bike on-throttle was

like pulling the cork out of a wine bottle,” Baldwin explained. “There’s this big effort, then-/?ü/?/-and you get a big surge from the engine.”

Baldwin and tuner Ray Plumb tackled the on-throttle problem by hacksawing “vacuum-breaker” slots in the throttle gates. This made throttle-up much easier and smoother.

What about powerband? “The camchain would break at 10,000 rpm, but it would pull from as low as 3000,” remembered Baldwin.

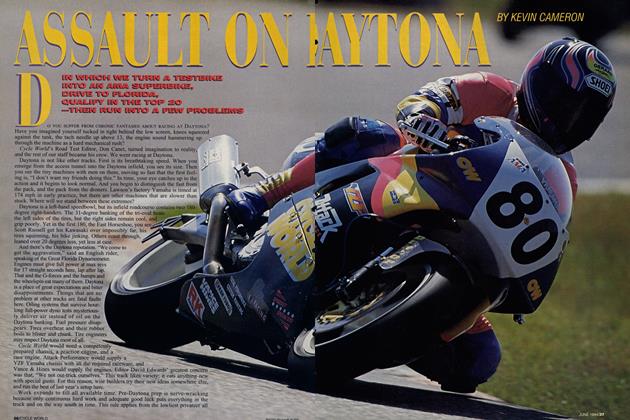

Now the 18-year-old bike was warmed-up and ready, so Freddie suited up and went out on it. At first, he went slowly-appropriate on a historic machine in unknown mechanical condition. Later, he rode it harder and Plumb (still with Honda after 19 years) reminded him, “Remember, they blow up at 10,000.”

“That’s why I’m only revving it to 9800,” was Freddie’s affable reply.

As the photo shows, this was a long bike-wheelbase is 58.5 inches. To avoid glacial handling, the team put a quickturning 16-inch front wheel in place of the stock 19-inch “flywheel.” As Baldwin told me recently, “That dropped it down a couple of inches in front. Then, they kicked the steering head in another inch. So it (the steeringhead angle) was really steep. It was the weirdest thing: Hard on the brakes, with the front end all the way down and the

rear end all the way up, you could get the front end ‘over center’-like negative trail. If it turned the slightest bit to either side, it would try to turn even more, and if it tucked, it was gone! It even got Freddie once. It was right on the edge.”

In effect, then, this bike had the quick steering of a 250 GP bike, joined to a bus’ wheelbase. “It didn’t feel like it was 58 inches,” Baldwin said. “But being so long (and therefore light at the rear), you could light up the back tire and slide it.” This lack of rear grip would be crucial at the wet start of the pivotal Seattle Superbike race in 1981. The Hondas went up in wheelspin off the line, while Kawasaki’s Eddie

Lawson got the drive and a commanding lead he held to the flag.

Crude equipment? Maybe, but those do-it-yourself experiments were the foundation of Superbike’s current sophistication. They were the school that educated essential men like Ray Plumb and Merlyn Plumlee-both at Willow on this day, looking after the new RC5 Is.

Want numbers? On a good day, this old bike might have made 145 horsepower at 9800 rpm and Superbikes of that era pushed close to 160 mph at Daytona.

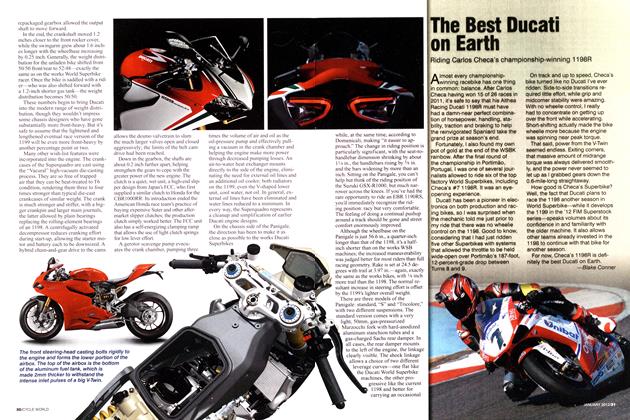

After a couple of sessions on the old air-cooled F, Spencer threw a leg over Duhamel’s RC. To eliminate the complication of starting rollers, these bikes sensibly have retained the streetbike’s electric starter. Freddie hit the button and he was off. Like the RSV Aprilia, the 51 makes a lot of valve noise because its geared cam drive has to

overcome all that valve-spring pressure, pushing the cams first this way, then the other. The exhaust sound is like that of the Ducati 996, but perhaps a bit less breathy, the individual pulses a little sharper. Instead of the side radiators of the streetbike, there is a top rad mounted conventionally, another mounted vertically in the left of the fairing opening, and an oil cooler in the mirror-image position-all safe from crashes. As with all Twins, total radiator area is small.

The exhaust system begins with two tapered headers in titanium, snaking all over the machine to join under the rider’s right foot, then splitting into two pipes serving the two mufflers. The titanium welding rivals the splendors of Tutankhamen’s treasures-wonderful!

Plumlee says of the heads, “It was kind of a shock. They look so plain inside, so much like...street parts.

That’s because they lack all the massage that’s been necessary over the years to make the RC45 what it was.” Honda engineers in Japan say this bike is “a much better platform than the RC45 was at its introduction.” The good lap times run at Phillip Island and Daytona tire tests show how close to right this bike is.

“The first thing I noticed was how well the RC51 changed directions, that

initial movement off-center,” Spencer explained. “Going from left to right, through Turns 3 and 4, it turned a lot better. Right off the bat, it was much better than the RC45. It’s smaller and more compact, but more comfortable and rider-friendly. I felt in control.” Duhamel concurred, saying that the RC’s front end has feel that the 45 never had. Power range? “It comes on at 7500-7800, and runs to 11,000-

11,400. It’ll pull at 6, but you aren’t going to win any races down there,” noted the sage-like Miguel.

Lofdahl summed up the day best by saying, “When you look at all the progress there’s been from 1980 until now, it makes you wonder what we’ll think of today’s bikes in another 20 years-what the breakthroughs will be that we’ll take for granted then.”

I hope to see it. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontFree Bikes And Other Myths

May 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsOpening the Eastern Gate

May 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCWorking All Night

May 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

May 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupTop Tourer? Honda Gl1800 Gold Wing

May 2000 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki Street-Traciker

May 2000 By Nick Ienatsch