Beguiling style

TDC

Kevin Cameron

JUST AS WE HATE TO SEE OURSELVES robotically buying soap or fast food because we’ve been dinned and blasted with ads for it, so I feel creeping embarrassment when I find product styling having its way with me. One day I laid out the remote controls for our family collection of obsolete VCRs. Even though I feel I should be pleased by the clean, planar lines of the older remotes, instead they look dated and shabby next to the swoopy organic shapes of the most recent ones.

This took me back to the 1950s when, with great effort, I struggled to carry some old furniture down from the attic and into my room.

“No, definitely not,” was my mother’s response. “All these Grand Rapids horrors have to go straight back upstairs.” I was crestfallen, and puzzled by how shape could be so important to people.

Many years later I would read about how fumishings-and even the cast-iron frames of industrial machine tools-became more and more ornate toward the end of the 19th century. Industrial Utopians of the time imagined that floral designs cast into machines would somehow soften the impact of 12-hour days. Such decoration culminated in a style so fussy and ornate that as a small boy I stood helpless in my grandmother’s parlor, afraid to sit anywhere for fear of damaging her precious 19th-century hideosities.

Then in the 1920s came a double whammy of fresh air. First the clean, utilitarian Scandinavian look, followed by the rediscovery of the similarly honest design of early American furniture. Cars quickly evolved from buggy-like rectangular boxes into smoother, cleaner, aero-inspired shapes.

These things come and go in cycles that will come again. Mentally I compare the plain appearance of an MV Agusta factory roadrace bike of the 1950s or ’60s with the infinitely more decorated look of today’s bikes covered with contrasting colors and varieties of shape. Or compare leather riding suits. The Mike Hailwood look was austere black. Then in the 1970s colored leathers arrived in the U.S., then multi-colors, with a sprouting of sponsor patches and the rider’s name. T oday this has evolved into veritable suits of lights criss-crossed by darts and angles, and given trans-human shape by sewn-in plastic knee, shoulder and elbow cups, plus the prominent aero bulge of the back protector. What men or gods are these? Sponsor logos are everywhere. Simplicity is nowhere to be found in a confiision of necessary commercial messages. It’s a great show, but somebody has to pay for it. Both the motorcycles and their riders have evolved into a style every bit as decorated in its way as my grandmother’s parlor.

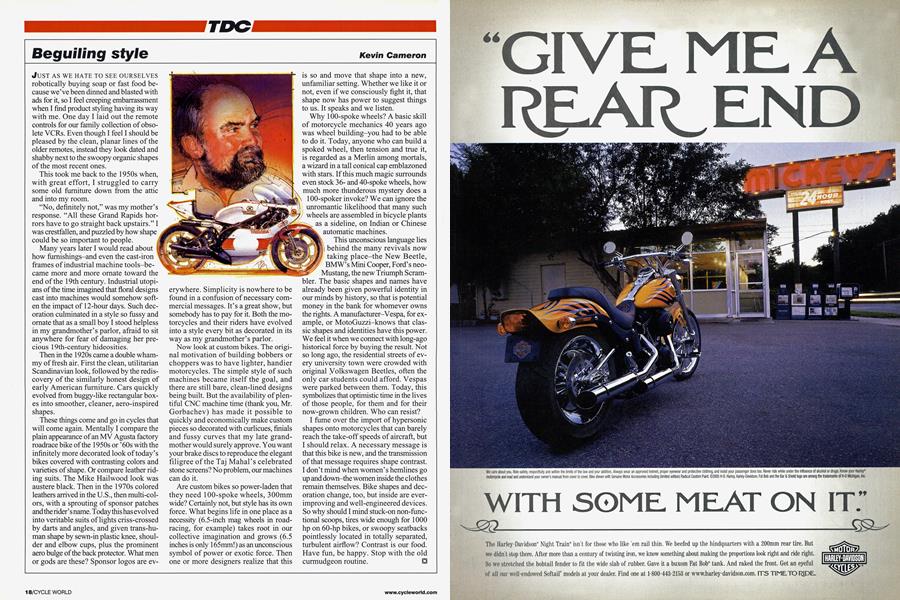

Now look at custom bikes. The original motivation of building bobbers or choppers was to have lighter, handier motorcycles. The simple style of such machines became itself the goal, and there are still bare, clean-lined designs being built. But the availability of plentiful CNC machine time (thank you, Mr. Gorbachev) has made it possible to quickly and economically make custom pieces so decorated with curlicues, finials and fussy curves that my late grandmother would surely approve. You want your brake discs to reproduce the elegant filigree of the Taj Mahal’s celebrated stone screens? No problem, our machines can do it.

Are custom bikes so power-laden that they need 100-spoke wheels, 300mm wide? Certainly not, but style has its own force. What begins life in one place as a necessity (6.5-inch mag wheels in roadracing, for example) takes root in our collective imagination and grows (6.5 inches is only 165mm!) as an unconscious symbol of power or exotic force. Then one or more designers realize that this is so and move that shape into a new, unfamiliar setting. Whether we like it or not, even if we consciously fight it, that shape now has power to suggest things to us. It speaks and we listen.

Why 100-spoke wheels? A basic skill of motorcycle mechanics 40 years ago was wheel building-you had to be able to do it. Today, anyone who can build a spoked wheel, then tension and true it, is regarded as a Merlin among mortals, a wizard in a tall conical cap emblazoned with stars. If this much magic surrounds even stock 36and 40-spoke wheels, how much more thunderous mystery does a 100-spoker invoke? We can ignore the unromantic likelihood that many such wheels are assembled in bicycle plants as a sideline, on Indian or Chinese automatic machines.

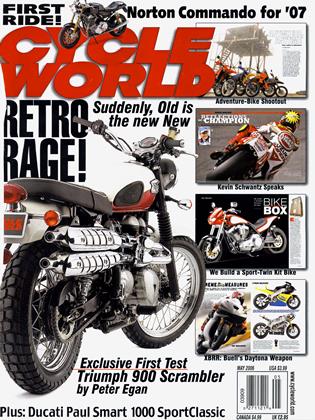

This unconscious language lies ; behind the many revivals now taking place-the New Beetle, BMW’s Mini Cooper, Ford’s neoMustang, the new Triumph Scrambler. The basic shapes and names have already been given powerful identity in our minds by history, so that is potential money in the bank for whomever owns the rights. A manufacturer-Vespa, for example, or MotoGuzzi-knows that classic shapes and identities have this power. We feel it when we connect with long-ago historical force by buying the result. Not so long ago, the residential streets of every university town were crowded with original Volkswagen Beetles, often the only car students could afford. Vespas were parked between them. Today, this symbolizes that optimistic time in the lives of those people, for them and for their now-grown children. Who can resist?

I fume over the import of hypersonic shapes onto motorcycles that can barely reach the take-off speeds of aircraft, but I should relax. A necessary message is that this bike is new, and the transmission of that message requires shape contrast. I don’t mind when women’s hemlines go up and down-the women inside the clothes remain themselves. Bike shapes and decoration change, too, but inside are everimproving and well-engineered devices. So why should I mind stuck-on non-functional scoops, tires wide enough for 1000 hp on 60-hp bikes, or swoopy seatbacks pointlessly located in totally separated, turbulent airflow? Contrast is our food. Have fun, be happy. Stop with the old curmudgeon routine. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue