TDC

Illusion, disillusion

Kevin Cameron

AS A SMALL BOY, I WHEEDLED MY mother to read to me the encyclopedia articles on “Motor Car” and “Aeroplane”—even though I couldn’t understand much of it. I liked things that moved under their own power. I liked the sounds they made and I liked the words used to describe them. I liked the pictures and diagrams.

But disillusionment was coming. When 1 looked at a car, I saw' the jutting exhaust pipe and 1 imagined rushing gases and streamlines of airflow. The shapes of hoods, fenders and windows, so carefully styled to suggest power and speed, worked upon my imagination exactly as intended.

Then one summer day, my jack-ofall-trades uncle was visiting. He had promised to make me a detailed model of a car out of modeling clay, and 1 held him to it. He sat on the porch next to flowering bushes, chatting with his sister, shaping chassis rails and other parts with his fingers. I besieged him with questions: “What’s that? How does it work? What’s a ball bearing?” Gradually the working parts were finished and he began on the fenders, the hood and the body. 1 was confused. The shapes of body parts had almost nothing to do with what lay inside them. All that suggestion of power and speed was just that-suggestion. Or worse, maybe it was a lie. Hoods weren't shaped like engines at al 1—they were just styling for people who would never look inside. Most of that elegantly shaped tin was empty, lacking any real purpose. It was a con.

This revelation switched my interest to more honestly shaped vehicles: racing cars, airplanes, motorcycles. In these machines, the form was a functional truth of some kind-not a suggestion, a lie or an advertisement.

So much for the sentiments of 8year-olds.

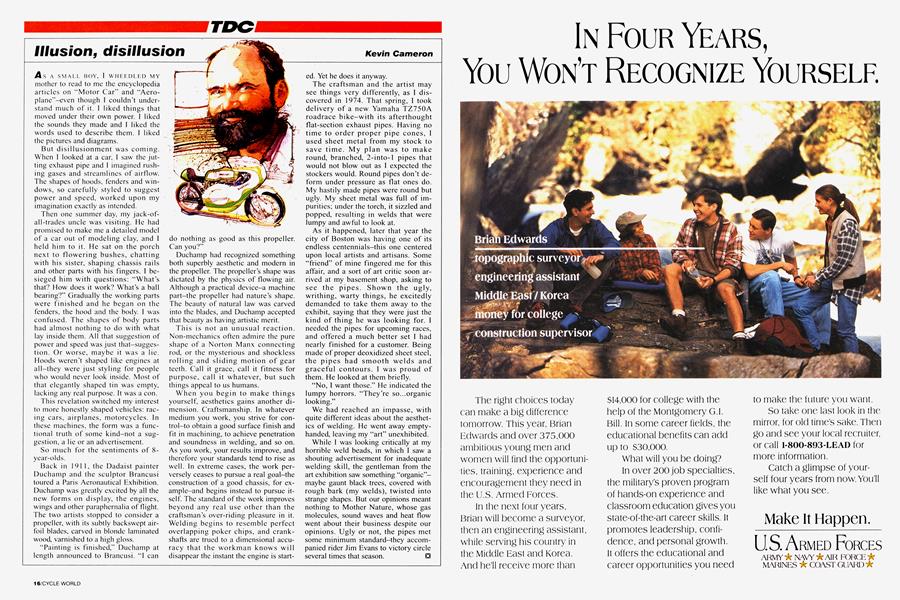

Back in 1911, the Dadaist painter Duchamp and the sculptor Brancusi toured a Paris Aeronautical Exhibition. Duchamp was greatly excited by all the new forms on display, the engines, wings and other paraphernalia of flight. The two artists stopped to consider a propeller, with its subtly backswept airfoil blades, carved in blonde laminated wood, varnished to a high gloss.

“Painting is finished,” Duchamp at length announced to Brancusi. “I can do nothing as good as this propeller. Can you?”

Duchamp had recognized something both superbly aesthetic and modern in the propeller. The propeller’s shape was dictated by the physics of flowing air. Although a practical device—a machine part-the propeller had nature’s shape. The beauty of natural law was carved into the blades, and Duchamp accepted that beauty as having artistic merit.

This is not an unusual reaction. Non-mechanics often admire the pure shape of a Norton Manx connecting rod, or the mysterious and shock less rolling and sliding motion of gear teeth. Call it grace, call it fitness for purpose, call it whatever, but such things appeal to us humans.

When you begin to make things yourself, aesthetics gains another dimension. Craftsmanship. In whatever medium you work, you strive for control-to obtain a good surface finish and fit in machining, to achieve penetration and soundness in welding, and so on. As you work, your results improve, and therefore your standards tend to rise as well. In extreme cases, the work perversely ceases to pursue a real goal-the construction of a good chassis, for example-and begins instead to pursue itself. The standard of the work improves beyond any real use other than the craftsman's over-riding pleasure in it. Welding begins to resemble perfect overlapping poker chips, and crankshafts are trued to a dimensional accuracy that the workman knows will disappear the instant the engine is started. Yet he does it anyway.

The craftsman and the artist may see things very differently, as I discovered in 1974. That spring, I took delivery of a new Yamaha TZ750A roadrace bike-with its afterthought flat-section exhaust pipes. Having no time to order proper pipe cones, I used sheet metal from my stock to save time. My plan was to make round, branched, 2-into-l pipes that would not blow out as I expected the stockers would. Round pipes don’t deform under pressure as flat ones do. My hastily made pipes were round but ugly. My sheet metal was full of impurities; under the torch, it sizzled and popped, resulting in welds that were lumpy and awful to look at.

As it happened, later that year the city of Boston was having one of its endless centennials-this one centered upon local artists and artisans. Some “friend” of mine fingered me for this affair, and a sort of art critic soon arrived at my basement shop, asking to see the pipes. Shown the ugly, writhing, warty things, he excitedly demanded to take them away to the exhibit, saying that they were just the kind of thing he was looking for. I needed the pipes for upcoming races, and offered a much better set I had nearly finished for a customer. Being made of proper deoxidized sheet steel, the pipes had smooth welds and graceful contours. I was proud of them. He looked at them briefly.

“No, I want those.” He indicated the lumpy horrors. “They’re so...organic looking.”

We had reached an impasse, with quite different ideas about the aesthetics of welding. He went away emptyhanded, leaving my “art” unexhibited.

While I was looking critically at my horrible weld beads, in which I saw a shouting advertisement for inadequate welding skill, the gentleman from the art exhibition saw something “organic”maybe gaunt black trees, covered with rough bark (my welds), twisted into strange shapes. But our opinions meant nothing to Mother Nature, whose gas molecules, sound waves and heat flow went about their business despite our opinions. Ugly or not, the pipes met some minimum standard-they accompanied rider Jim Evans to victory circle several times that season. E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

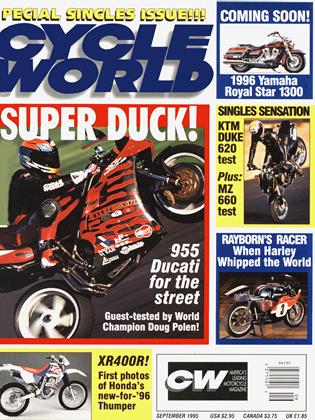

Up FrontSingle-Minded

September 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Bikes of Lago Di Como

September 1995 By Peter Egan -

Departments

DepartmentsLetters

September 1995 -

Roundup

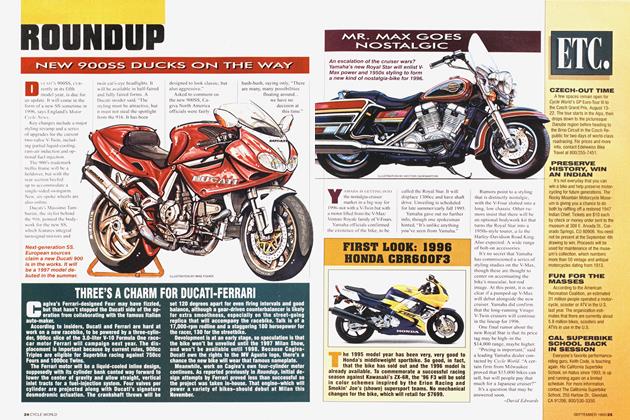

RoundupNew 900ss Ducks On the Way

September 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupThree's A Charm For Ducati-Ferrari

September 1995 -

Roundup

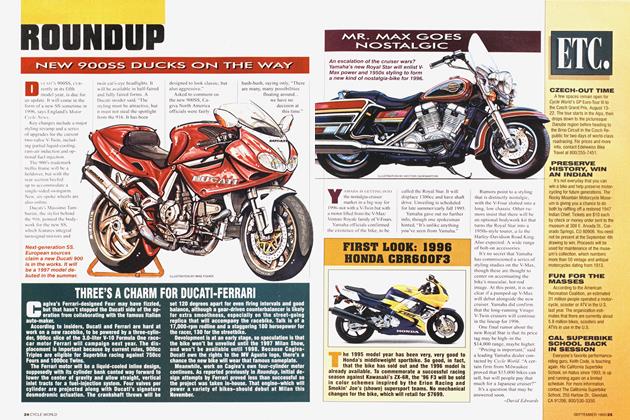

RoundupMr. Max Goes Nostalgic

September 1995 By David Edwards