Indianapolis and Tomorrow

What does the future hold for MotoGP?

KEVIN CAMERON

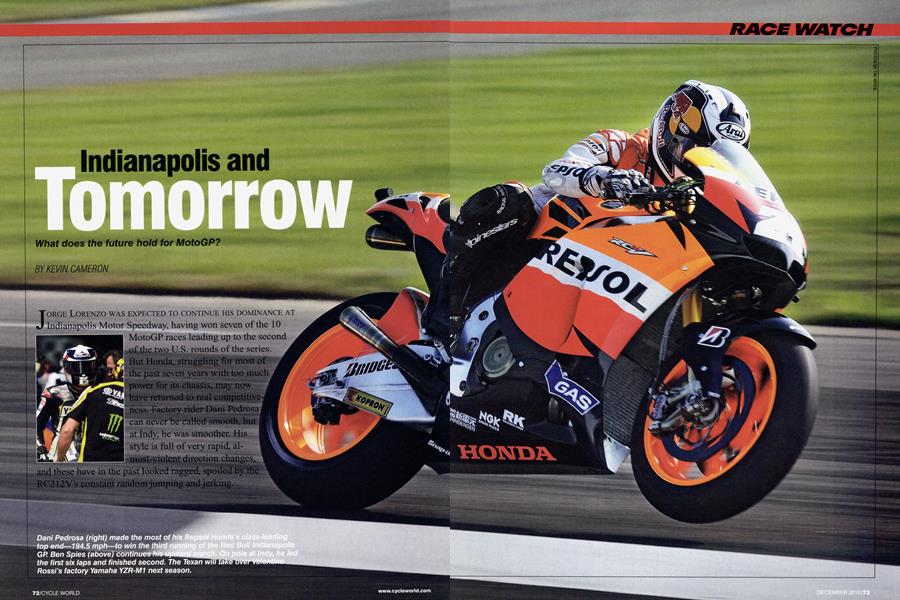

JORGE LORENZO WAS EXPECTED TO CONTINUE HIS DOMINANCE AT Indianapolis Motor Speedway, having won seven of the 10 MotoGP races leading up to the second of the two U.S. rounds of the series. But Honda, struggling for most of the past seven years with too much power for its chassis, may now have returned to real competitiveness. Factory rider Dani Pedrosa can never be called smooth, but at Indy, he was smoother. His style is full of very rapid, almost-violent direction changes, and these have in the past looked ragged, spoiled by the RC212V's constant random jumping jerking

RACE WATCH

By comparison, Lorenzo's Yamaha YZR-M1 is a paragon of smoothness and control. And 2007 MotoGP World Champion Casey Stoner seems to have gone slightly slower this season as changes to the Ducati GP1O have helped teammate Nicky Hayden go faster. Stoner is fast, but his title-winning combination of advanced electronics, Ducati horsepower and Bridgestone tires is unique no longer. Everyone's on spec Bridgestones now. Yamaha caught up in electronics in 2008, and now Honda, hiring away key Yamaha software writ ers last year, has caught up, as well. And they have pneumatic-valve horsepower.

The new element has been Ben Spies on the satellite Tech 3 Ml. Spies seems to me like an entire general staff, mak

ing strategic and tactical plans a mile a minute, studying details, forgetting nothing, learning new things instantly. Okay, maybe his bike doesn't have Yamaha's latest chassis or trickest engine bits. But on Indy's worse-thanever bumps, he fell in practice only once to Valentino Rossi's three times. I think Spies made himself a map of the smooth lines that was better than any one else's, with constant updates. With that information, he put himself on pole (this is his first year in MotoGP, remember) and led the race for six laps-until Pedrosa motored effortless ly past him on the straight and moved on out of reach, not falling down as so often in the past.

Not falling is a sign that a rider has a proper strategic reserve. No one wins championships by riding on the edge. Jeremy Burgess, Rossi's crew chief, said, "I want my rider to win using 96 percent. The other four percent are for when you really need them?'

cycleworld.com/indygp

p1es teammate, uonn tawarus, asked about the pavement, replied, "Bumps? I thought they were jumps." Does the Ducati lack front-end "feel?" Feel is warning that you are nearing the grip limit-essential if you are to ride near the limit, rather than either just go slow or step into empty space. Stoner said, "When you think it's the front, it's the rear," but he also complained of lack of confidence, of having "small loses" at the front. Onlookers see him slightly lift the bike; is he stopping a "lose?" In any case, after a fall in practice, Stoner wasn't pushing to the limit, whether he could "feel" it or not.

At the end of 28 laps, it was Pedrosa by 3.5 seconds from Spies, then Lorenzo (who looked thoroughly dis gusted in the press conference). Rossi, still recovering from his broken leg, had pulled himself up to Dovizioso (second factory Repsol Honda) and passed him for fourth. Stoner crashed out early after passing Hayden.

Tire choices had a tale to tell. Only four riders-Pedrosa, Dovizioso, Stoner and Edwards-chose the harder of the two rears. Pedrosa said, "I had no choice" because his aggressive engine puts so much heat into the tire.

Indianapolis raises an important question: The present corner-speed rid ing style and the very limited "lateral suspension" provided by frame flex are at odds with bumps of Indianapolis size. Spring rates must be hard enough not to bottom under the 2g corner load of today's tires. Are GP bikes now as overspecialized as Formula One's al most-suspension-less "500-horsepower go-karts" of the 1980s? Should bikes again adapt to bumps, or should bumps adapt to bikes?

The rules changes coming in 2012 make GP racing a "lame duck" as old classes live out the time left to them. Moto2 has this year replaced 250cc GP with prototype chassis powered by "spec" Honda 600cc four-cylinder engines. Soon the 125cc GP class, cur rently dominated by Aprilia and Derbi two-stràke Singles making 50-5 5 hp, will be replaced by some kind of 250cc four-stroke Singles of as-yet unknown type. Will they have an 81mm bore limit? Does the proposed 20,000 Euro engine price ceiling make it a claiming class? May constructors employ con rods, valves and wrist-pins made of titanium aluminide?

MotoGP itself will in 2012 adopt 1000cc engines of four cylinders and six speeds with a maximum bore of 81mm and fuel capacity of2l liters (5.5 gallons). For at least the first year, the present 800cc machines will be permitted to compete.

This is a combi nation of market ing, cost control and change for its own sake. Old time pundits call for a return to liter engines, saying it will bring back spectacular wheel spin and tail-sliding antics, which will "make racing excit ing again." Critics have said 800cc corner speeds prevent passing and "make racing boring." Some ridersRossi among them-have called for limits on the use of electronics. Honda is suspected of backing rules changes just because change gives its greater resources more leverage. While we mull the questions of speed, excitement and potential for injury, we can consider something else. All forms of sport-even including specialized activities like equestrian dressage-are seeing their financial futures in forsaking enthusiast audi ences in favor of the mass viewer. Will racing's survival hinge upon trans forming it into the "Joe Six-Pack Pure Excitement Series?"

MotoGP is currently a close contest among five top riders: Rossi, Lorenzo, Stoner, Pedrosa and, lately, American Spies, with Dovizioso close behind. But wait: In the supposedly much more exciting and dynamic past of 500cc two-strokes, there were seldom more than two contenders (Kenny Roberts and Barry Sheene or Freddie Spencer and Eddie Lawson), and only very oc casionally three (Wayne Rainey, Kevin Schwantz and Lawson). Are people complaining about too much competi tion now?

There is moaning that the electron ics make it possible for "undeserving persons" to ride above their real skills. Electronics make racing too easy? If these alleged "electronic prodigies" were removed, only Rossi might remain to reign in solitary excellence as Mick Doohan did for five straight years in the 1990s.

What made the tail-sliding 500s so exciting? Their defects! Two-strokes' steep powerbands prevent the rider from applying power smoothly, so he does most of his turning early, then lifts the bike up off the edges of its tires and gasses it, steering with the throttle because there's too little weight on the front tire for it to steer. Now, the excite ment starts, as the spinning rear tire suddenly grips, threatening to highside the rider. So many were highsided in 1989 that the FIM instituted the 130kilogram (286-pound) minimum weight and threatened to impose intake restric tors. That situation was retrieved when in 1990, the makers adopted electronic torque controls to smooth off-corner acceleration. Many long-standing lap records were set the next year.

I went to visit Doohan just after he retired and asked him why I didn't see point-and-shoot tail-sliding much any more. He replied that as long as the tire stays in good condition, a corner-speed style is fastest. When the tire fades, he said, riders revert to point-and-shoot for its security.

When 990cc four-strokes came in 2002, it was suddenly possible to apply engine power very smoothly (the im mediately dominant Honda RC21 1V V-Five was superlative at this). That further encouraged the corner-speed style, because even with the bike on the edges of its tires, smooth power could be applied to begin acceleration.

In the years that followed, every increase in smoothness and control brought new lap records. The faster you go and the more you know about what you are doing, the less unexplored margin there is for brave passing maneuvers.

Many people are excited by Moto2, with its 42 starters all trying to be first into Turn 1. Race direction has more than once sternly lectured the Moto2 riders not to do this, but they know their only chance is to be in the top group at the end of lap one. The Moto2 race at Indianapolis had the expected lap-one crash, red flag and restart. When I asked spectators the names of Moto2 riders or teams that interest them, they couldn't think of any. Maybe that will take time, and heroes will arise. Or maybe Moto2 will remain just "the excite ment class."

I spoke with Tohru Ubukata, Bridgestone's MotoGP engineer, and asked him if the 2012 return to 1000cc engines would bring back a buckaroo tail-sliding riding style. He explained that wheelspin would put more heat into the tire, causing a more rapid loss of grip. He said that only small modi fications would be necessary to adapt present tire constructions for use on l000s. The high corner-speed style will continue in the new formula.

Management could change this by executive fiat. They could phone Goodyear in Akron, Ohio, and ask them to bring back the 1977-era #1734 tire with which Kenny Roberts perfected the point-and-shoot style on 120-hp bikes. That good old 1734 tire required a rim just a bit over half the width of those on today's MotoGP bikes. -

Let's think about 250cc four-strokes as a replacement for the present 125s. If we rev an 81.0 x 48.4mm Single to the same peak piston acceleration found in present 600cc sportbikes at redline, we get the same power as 125cc two-strokes--about 55 hp. Four such 250s would about equal the power of a modern 1000cc World Superbike racer. If we rev them to the 10,000g piston acceleration once reached in F-i, we get maybe 65 hp. But why bother? Why not just make a spec class based on the Aprilia two-stroke engine, which is already in pro duction, and ask that company to build it to the desired price ceiling? Meanwhile, American dirt-track, as seen at the Indy Mile on Saturday night, has everything the cx perts say is lacking in MotoGP: close racing in a pack of closely equal riders and machines without elec tronic interference. Yet dirt-track has been in decline for years.

Where will racing turn? Will the business side extend its control over design until racing no longer leads the development of the motorcycle? Can that serve the interests of the industry? Can compromise be reached between enthusiast and mass audiences, be tween the racing we have known and the increasingly controlled spectacle that may lie ahead?

What if the enthusiasts leave and the mass audience stays tuned to soccer? Then, to use an English expression, rac ing might "fall between two stools."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontCottage Industry

December 2010 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupHyde Harrier

December 2010 By Gary Inman -

Roundup

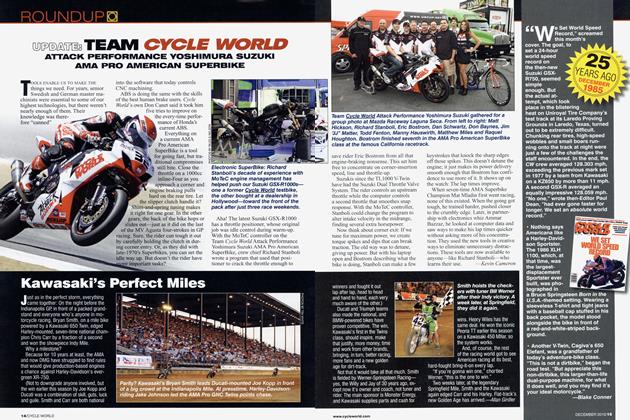

RoundupUpdate: Team Cycle World

December 2010 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

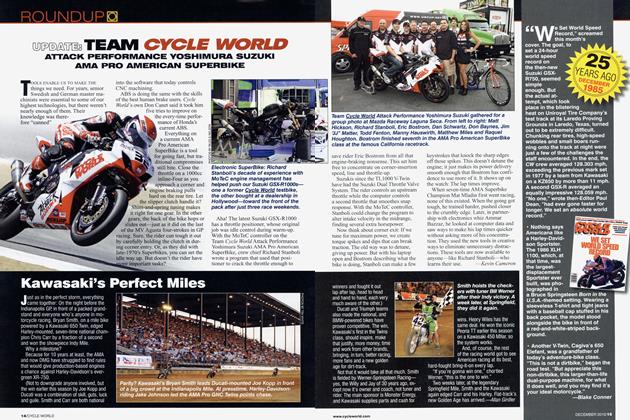

RoundupKawasaki's Perfect Miles

December 2010 By Allan Girdler -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago December 1985

December 2010 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

Roundup2011: What's Just Over the Horizon?

December 2010 By Bruno Deprato, Matthew Miles