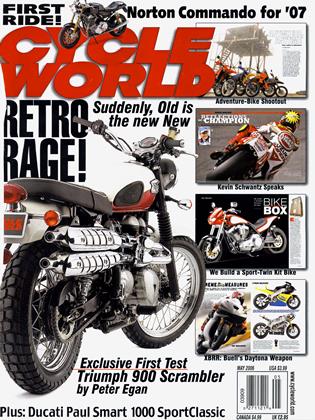

Retroactivity

UP FRONT

David Edwards

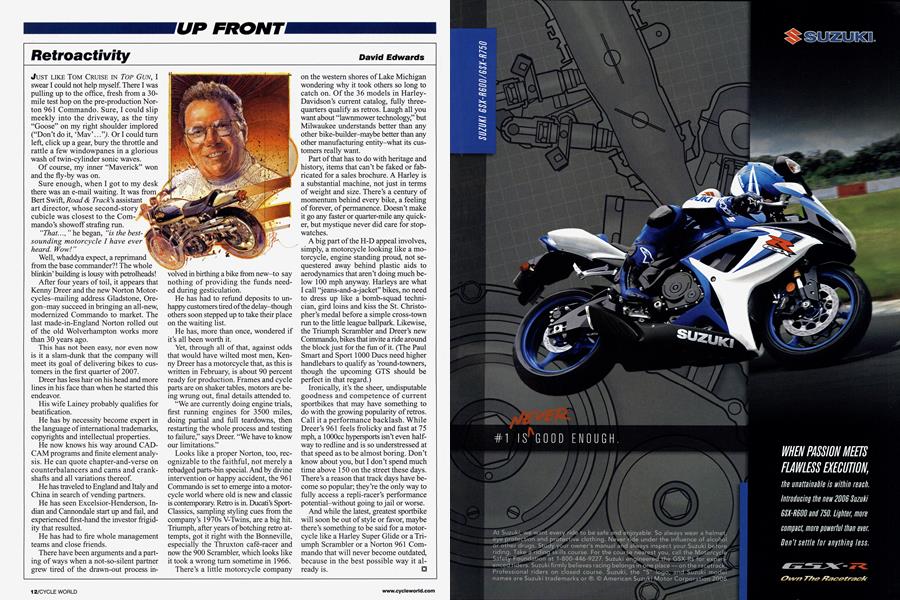

JUST LIKE TOM CRUISE IN TOP GUN, I swear I could not help myself. There I was pulling up to the office, fresh from a 30mile test hop on the pre-production Norton 961 Commando. Sure, I could slip meekly into the driveway, as the tiny “Goose” on my right shoulder implored (“Don’t do it, ‘Mav’..."). Or I could turn left, click up a gear, bury the throttle and rattle a few windowpanes in a glorious wash of twin-cylinder sonic waves.

Of course, my inner “Maverick” won and the fly-by was on.

Sure enough, when I got to my desk there was an e-mail waiting. It was Bert Swift, Road & Track's assistant art director, whose second-story cubicle was closest to the Commando’s showoff strafing run.

“That..., ” he began, “is the bestsounding motorcycle I have ever heard. Wow!”

Well, whaddya expect, a reprimand from the base commander?! The whole blinkin’ building is lousy with petrolheads!

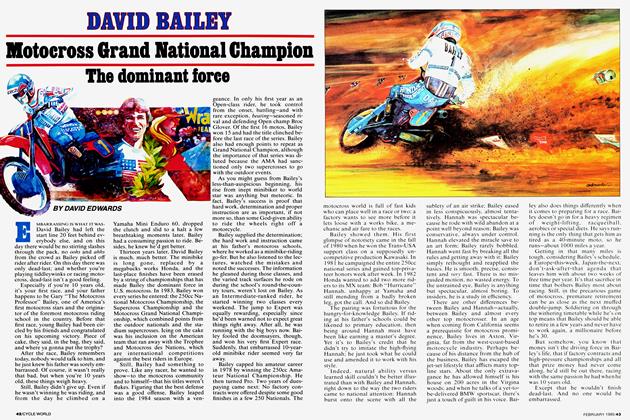

After four years of toil, it appears that Kenny Dreer and the new Norton Motorcycles-mailing address Gladstone, Oregon-may succeed in bringing an all-new, modernized Commando to market. The last made-in-England Norton rolled out of the old Wolverhampton works more than 30 years ago.

This has not been easy, nor even now is it a slam-dunk that the company will meet its goal of delivering bikes to customers in the first quarter of 2007.

Dreer has less hair on his head and more lines in his face than when he started this endeavor.

His wife Lainey probably qualifies for beatification.

He has by necessity become expert in the language of international trademarks, copyrights and intellectual properties.

He now knows his way around CADCAM programs and finite element analysis. He can quote chapter-and-verse on counterbalancers and cams and crankshafts and all variations thereof.

He has traveled to England and Italy and China in search of vending partners.

He has seen Excelsior-Henderson, Indian and Cannondale start up and fail, and experienced first-hand the investor frigidity that resulted.

He has had to fire whole management teams and close friends.

There have been arguments and a parting of ways when a not-so-silent partner grew tired of the drawn-out process inin birthing a bike from new-to say nothing of providing the funds needed during gesticulation.

He has had to refund deposits to unhappy customers tired of the delay-though others soon stepped up to take their place on the waiting list.

He has, more than once, wondered if it’s all been worth it.

Yet, through all of that, against odds that would have wilted most men, Kenny Dreer has a motorcycle that, as this is written in February, is about 90 percent ready for production. Frames and cycle parts are on shaker tables, motors are being wrung out, final details attended to.

“We are currently doing engine trials, first running engines for 3500 miles, doing partial and full teardowns, then restarting the whole process and testing to failure,” says Dreer. “We have to know our limitations.”

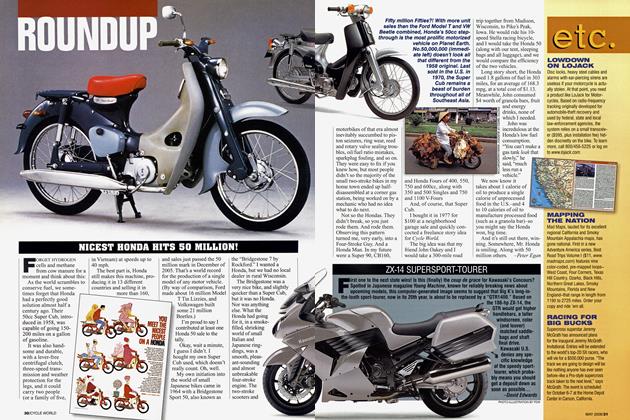

Looks like a proper Norton, too, recognizable to the faithful, not merely a rebadged parts-bin special. And by divine intervention or happy accident, the 961 Commando is set to emerge into a motorcycle world where old is new and classic is contemporary. Retro is in. Ducati’s SportClassics, sampling styling cues from the company’s 1970s V-Twins, are a big hit. Triumph, after years of botching retro attempts, got it right with the Bonneville, especially the Thruxton café-racer and now the 900 Scrambler, which looks like it took a wrong turn sometime in 1966.

There’s a little motorcycle company on the western shores of Lake Michigan wondering why it took others so long to catch on. Of the 36 models in Harley -Davidson’s current catalog, fully threequarters qualify as retros. Laugh all you want about “lawnmower technology,” but Milwaukee understands better than any other bike-builder-maybe better than any other manufacturing entity-what its customers really want.

Part of that has to do with heritage and history, items that can’t be faked or fabricated for a sales brochure. A Harley is a substantial machine, not just in terms of weight and size. There’s a century of momentum behind every bike, a feeling of forever, of permanence. Doesn’t make it go any faster or quarter-mile any quicker, but mystique never did care for stopwatches.

A big part of the H-D appeal involves, simply, a motorcycle looking like a motorcycle, engine standing proud, not sequestered away behind plastic aids to aerodynamics that aren’t doing much below 100 mph anyway. Harleys are what I call “jeans-and-a-jacket” bikes, no need to dress up like a bomb-squad technician, gird loins and kiss the St. Christopher’s medal before a simple cross-town run to the little league ballpark. Likewise, the Triumph Scrambler and Dreer’s new Commando, bikes that invite a ride around the block just for the fun of it. (The Paul Smart and Sport 1000 Dues need higher handlebars to qualify as ’round-towners, though the upcoming GTS should be perfect in that regard.)

Ironically, it’s the sheer, undisputable goodness and competence of current sportbikes that may have something to do with the growing popularity of retros. Call it a performance backlash. While Dreer’s 961 feels frolicky and fast at 75 mph, a lOOOcc hypersports isn’t even halfway to redline and is so understressed at that speed as to be almost boring. Don’t know about you, but I don’t spend much time above 150 on the street these days. There’s a reason that track days have become so popular; they’re the only way to fully access a repli-racer’s performance potential-without going to jail or worse.

And while the latest, greatest sportbike will soon be out of style or favor, maybe there’s something to be said for a motorcycle like a Harley Super Glide or a Triumph Scrambler or a Norton 961 Commando that will never become outdated, because in the best possible way it already is. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue