Conversations with the King

Kenny Roberts on the USGP, Wayne Rainey, cornering styles and wild rumors

KEVIN CAMERON

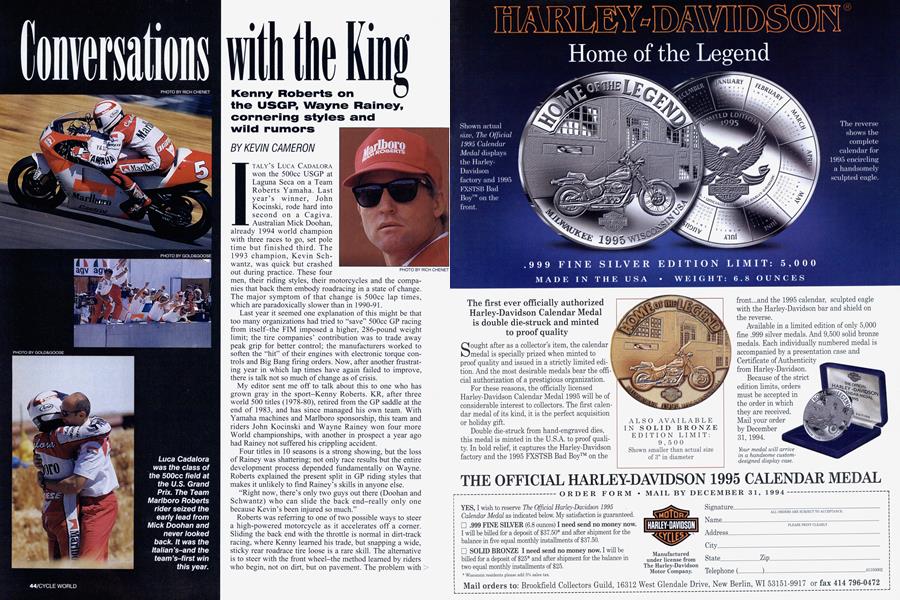

ITALY’S LUCA CADALORA won the 500cc USGP at Laguna Seca on a Team Roberts Yamaha. Last year’s winner, John Kocinski, rode hard into second on a Cagiva. Australian Mick Doohan, already 1994 world champion with three races to go, set pole time but finished third. The 1993 champion, Kevin Schwantz, was quick but crashed out during practice. These four

men, their riding styles, their motorcycles and the companies that back them embody roadracing in a state of change. The major symptom of that change is 500cc lap times, which are paradoxically slower than in 1990-91.

Last year it seemed one explanation of this might be that too many organizations had tried to “save” 500cc GP racing from itself-the FIM imposed a higher, 286-pound weight limit; the tire companies’ contribution was to trade away peak grip for better control; the manufacturers worked to soften the “hit” of their engines with electronic torque controls and Big Bang firing orders. Now, after another frustrating year in which lap times have again failed to improve, there is talk not so much of change as of crisis. My editor sent me off to talk about this to one who has grown gray in the sport-Kenny Roberts. KR, after three world 500 titles (1978-80), retired from the GP saddle at the end of 1983, and has since managed his own team. With Yamaha machines and Marlboro sponsorship, this team and riders John Kocinski and Wayne Rainey won four more World championships, with another in prospect a year ago had Rainey not suffered his crippling accident. Four titles in 10 seasons is a strong showing, but the loss of Rainey was shattering; not only race results but the entire development process depended fundamentally on Wayne. Roberts explained the present split in GP riding styles that makes it unlikely to find Rainey’s skills in anyone else. “Right now, there’s only two guys out there (Doohan and Schwantz) who can slide the back end-really only one because Kevin’s been injured so much.” Roberts was referring to one of two possible ways to steer a high-powered motorcycle as it accelerates off a corner. Sliding the back end with the throttle is normal in dirt-track racing, where Kenny learned his trade, but snapping a wide, sticky rear roadrace tire loose is a rare skill. The alternative is to steer with the front wheel-the method learned by riders who begin, not on dirt, but on pavement. The problem with > front steer is that it limits acceleration; as the rider rolls on the throttle, weight is transferred off the front wheel, reducing its grip, making the machine run wide. Front-steer riders try to raise their corner speed as high as possible, which reduces the amount of acceleration needed. This recovers some front grip, but acceleration is still postponed.

The tail-slider’s method is to enter the comer at less-thantraction-limited speed, hook the turn around early (“square it off’), and then use the large remaining part of the turn as an “acceleration patch,” lifting the bike up early to accelerate hard on a widening line. By contrast, the front-steer, or “corner-speed” method used by 125 and 250cc riders uses a line of largest possible radius through the turn-entering high, apexing low, exiting high-riding it at traction-limited maximum speed.

The tail-sliding method makes available more of the turn for acceleration, and 500s accelerate a lot better than they

turn. The result is that, although the front-steer method provides faster entry and higher corner speed (these riders are visibly leaned over farther), the tail-slider’s earlier acceleration gives him a higher exit speed that is an advantage all the way down the next straight. Naturally, a tire that is near its traction limit from cornering load cannot simultaneously provide forward thmst for acceleration; only as the bike is lifted up

from full lean does surplus traction for acceleration appear. This is what delays the front-steerer’s acceleration.

Roberts listed a second disadvantage of high corner speed: increased risk through the whole comer.

“Watch any 250 race,” Roberts said. “At least two guys out of the leading group will fall down. When you push right to the edge through the whole turn like that, it only takes a little mistake.”

Riding on comer speed, a racer is completely committed to his wide line; any error will put him off. With the tires at the traction limit, the risk is constant and high. But the rearsteer rider chooses the sliding rate with his right hand. If it’s too much, he can reduce it.

“We could go (at only) 90 percent and still go faster (than a front-steerer). When you square off the comer, you’re not right on the edge,” said Roberts.

Why do so few riders slide the back tire? For answer, KR turned to a subject that has occupied him for more than a decade: rider training.

“I’ve ridden a lot of bikes-roadracers, motocrossers, even trials bikes-and they all work the same,” Roberts said, before bringing in a golf analogy. “Everybody’s got a little different swing. But there’s only one basic swing, and if you don’t have it, you can’t play. If young riders can get some training in the theory of how to ride, they’ll be able to ride...whatever. Lawson and Rainey learned to ride on torque bikes that would spin the tire (the 1025cc Kawasaki Superbike of the early ’80s for Lawson, a Harley dirt-tracker for Rainey).”

The basic fact about motorcycles is that they are high, short-wheelbase vehicles, and so are subject to extreme weight transfer (wheelies, stoppies). They accelerate better > than they turn because they have a high power/weight ratio but little rubber on the road. These simple truths seem to imply the value of steering the rear wheel with the throttle.

On conditioning: "These young riders can't even get a barbell up oft their chests."

Today, roadracers mainly come up by three paths: 250, production bike and Superbike. But GP 500s are unique in their high-torque power delivery.

“People don’t ride a 250 that way (tail-sliding)-they could, but they don’t-and production bikes don’t have the torque. Superbikes have a lot of power now, but it’s rpm power, so they ride them more like 250s-high corner speed,” said Roberts.

He also talked about physical conditioning: “The only

way anybody’s going to beat Doohan is to wear him out, get him to make a mistake, but that’s not going to happen when these young riders can’t even get a barbell up off their chests. One guy couldn’t even work the exercise bicycle to warm up. A physical wreck.”

Roberts’ unstated question was how can a physical wreck hope to control a sliding motorcycle through a whole race? More to the point, I asked him if his lead rider, Luca Cadalora, was any more willing now to train than he had been when he rode 250s. KR made a rueful face, shaking his head.

He went on to describe how Rainey could handle a bike that was bouncing, chattering and sliding-a sort of controllable chaos. Rainey had the necessary physical and mental stamina to hold the pace.

Cadalora has found his present success largely in a modified high-comer-speed style. Mick Doohan, Roberts’ example of a tail-slider, has chosen a low-horsepower engine set-up this year and has been all but unbeatable with it. At any given point on comer exits, Doohan sounds to have the throttle open further than other riders, but his lines are little different. He says the computer shows him feeding in power gently and early-not in the classic burst that gets the tire sliding. If this is tail-sliding, it is tempered with considerable comer speed. John Kocinski, who finished second at Laguna, is another rider frequently criticized for trying to ride a 500 like a 250. Kevin Schwantz, the 1993 champion, has, according to tech manager Stu Shenton, changed his style towards high comer speed, to take pressure off his frequently injured wrist. Evidence visible at Laguna suggests that a convergence of styles is happening-whether by intent or by necessity.

Roberts spoke again about the failure of 500 lap times to fall, despite dramatic drops in 250 and, especially, 125cc times.

“You can get into a kind of mind-game,” he remarked. “With what we had back in 1991, we’d finish as much as a minute ahead of where we are now. Back in 1991, we had maybe 160 horsepower. Now we’re up a clear 30 on that. (Tire) sidegrip is better now. With this...Big Bang engine, we have better acceleration. But lap times are slower. Grip is up, comer speed is up, but lap time is slower.

“Our job is to win on the day. That may mean dropping back to what we had in 1991 or ’92 to do it (this refers to the much-publicized use of earlier chassis, fork and engine setups in place of the latest designs). The factory’s job is to find a way ahead,” Roberts added.

sponsors: "The Marlboro people want to win, not hear about how bad the Japanese economy is.,,

Then he touched on forces that limit R&D at Yamaha, namely the Japanese recession and too much success: “The Marlboro people want to win. When they talk to Yamaha, they just want results, not to hear about how bad the Japanese economy is. That sponsor is used to winning a championship every year, and last year, before Wayne’s accident, it was clear that we were winning the championship. Naturally, Yamaha cut back.”

Another of Roberts’ concerns is the current 500cc weight minimum of 286 pounds. “It’s too much. Most riders just can’t do it. We’re trying to get that changed,” he said.

I remarked that Team Roberts is known for its multi-talented staff and independent development work. Hasn’t this

helped them since Rainey’s tragedy?

“What we can do,” he replied,

“is get more bottom power, more mid-power, whatever, but we can’t make big engineering changes.”

I asked whether they are now sure of a future development direction. A year ago in Australia they had been in a quandary over the 1993 Yamaha chassis.

“Yamaha made the chassis we thought we wanted-stiffer, quickersteering, and so on-and it didn’t work. What’s needed is a complete re-engineering. But that kind of change means more than the old engine in a new chassis.”

I repeated Roberts’ list of improvements-more power, more grip, Big Bang engine-and suggested that they all might make it harder to snap the back end loose, that the present course of development in effect makes it harder to be a tail-slider. He agreed.

The rumor mill predicts a Roberts/Doohan/Honda/ Marlboro alignment in 1995. This would join the Roberts team to what it needs-a rear-steer rider and deep R&D capability, while joining Honda to what it needs-a major outside sponsor. I asked about it.

Roberts replied that this kind of press speculation always happens when there’s a change.

“Back when we lost Randy (Mamola, who left Team Roberts for Honda in 1985), it was the same thing. If a journalist sees me talking to Honda people, then there is right away this cloud of rumor. I read all the proposals I get. I never feel so confident and set up that I would ignore a serious proposal.”

At the end of our conversation, I asked if the pressures of 500cc racing-self-imposed or otherwise-aren’t too much for most men. Doesn’t it help, for instance, to have a family?

“To be...normal,” Roberts amended, emphasizing the word. “Like Wayne. Yes.”

Laguna practice began two days later. Cadalora and Kocinski, notorious front-steerers, traded fast times until Doohan took pole by .008 second during a wind lull in the last 10 minutes of practice.

Doohan had been dominant in 1992 with the Big Bang engine, until his injury. Then in ’93 he had looked lost, with too much power and too many injuries. Kevin Schwantz described Honda’s remarkable 1994 progress. “The first three races, they didn’t look like they had anything special, and then I had the good fortune-to win in Japan, so I thought, ‘Great, when we get to Europe, Ell have my way with them.’”

On R&D: "We can get more bot tom power, more midpower, but we can't make big engineering changes... that's the factory's job."

He rubbed his hands together gleefully.

“Last year, I’d just wait for half-distance, knowing Doohan would bum his tires up, then I’d ease on by. But they put on a test just before Spain, and whatever they learned there, well, Doohan had his way with us instead,” Schwantz said.

Watching practice, it was clear that this Honda is completely different from last season’s. The ’94 has super-progressive, smooth power that can be fed in early, without surprises-a complete break with last year’s explosive powerhouse. Rumor holds that Honda, too, has gone back to a ’92 engine and other components.

Comparing riders at every comer revealed only marginal differences; maybe Doohan does tum a little sooner, leaving

more room for acceleration—but on this lower-gear track it was a difference of only 3-6 feet in apex. Are the styles really so different?

Gone are the 1988 days of violent slip-and-grip acceleration, in which top riders pushed as close as possible to high-siding out of every lowergear comer. Smoother powerbands, the Big Bang concept and more forgiving tires have done this. Listening to Cadalora’s Yamaha being warmed up was instructive; it runs more smoothly and sweetly down low than any streetbike, not like a racing engine at all. Although Doohan was getting strong drives off the comers,

his bike was only fifthto seventh-fastest through the Turn One speed trap. Raw power is out.

This leaves us with a conundrum.

Technical developments that continue to make 125s and 250s faster are somehow making 500s slower. The smaller bikes can use more power because they have so little. They can use more grip because, without the acceleration of a 500, they depend on comer speed for a good lap time.

The effect on 500s is different. Everything that increases grip makes rear-steering harder to do. That includes smoother power, because harsh power was often used in the past as a tool to induce sliding. Tire development tends towards higher carcass stiffness, which in turn requires more compliant suspension-yet hard suspension has long been a tool used to make sliding easier. This forces rearsteer riders to modify their style, to converge towards the front-steer, high-corner-speed style that thrives on good grip and solid hook-up. At Laguna, only six-tenths of a second separated this year’s fastest race lap (Kocinski the front-steerer) from the record 1990 race lap (Schwantz the rear-steerer).

Can front-steer 500cc riders like Cadalora and Kocinski, assisted by tire and other development, eventually lift lap times out of the present depression? Can the separate development of tires, suspension, chassis and engine be somehow re-directed to again serve the needs of rear-steering? Or will the two styles slowly merge into each other, a marriage forced by development itself? We have to let the future provide the answer.

Keep your stopwatch, binoculars and note pad handy. □

On 1995: "I read all the proposals I get. • never feel so confi dent that I would ingnore a serious proposal."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

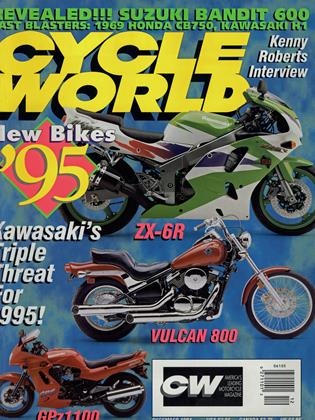

Up Front

Up FrontThe Endless Ride

December 1994 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsSaving For A Vincent

December 1994 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCCharacter Assassination

December 1994 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1994 -

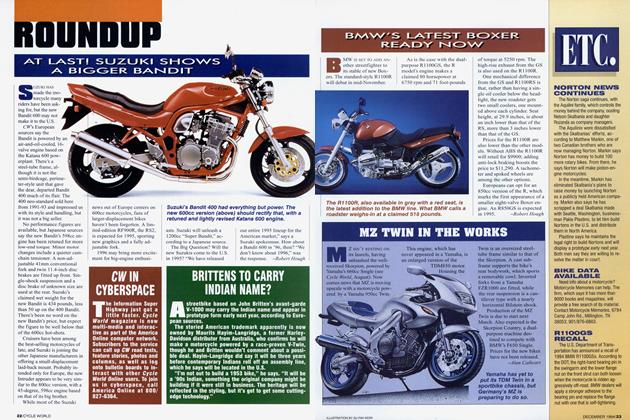

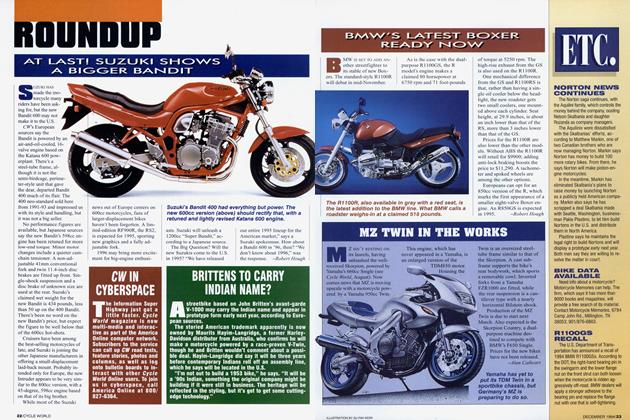

Roundup

RoundupAt Last! Suzuki Shows A Bigger Bandit

December 1994 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupCw In Cyberspace

December 1994