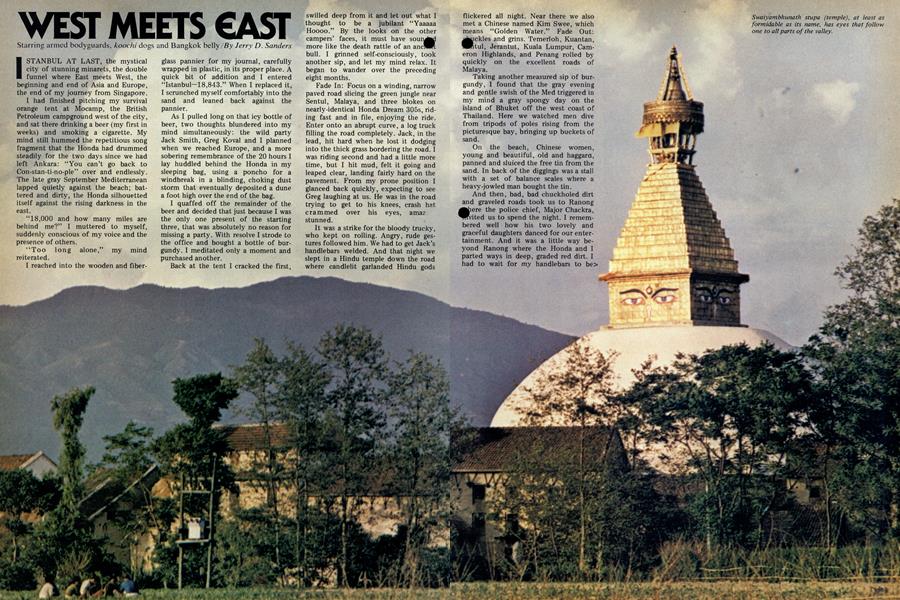

WEST MEETS CAST

Starring armed bodyguards, koochi dogs and Bangkok belly

Jerry D. Sanders

ISTANBUL AT LAST, the mystical city of stunning minarets, the double funnel where East meets West, the beginning and end of Asia and Europe, the end of my journey from Singapore.

I had finished pitching my survival orange tent at Mocamp, the British Petroleum campground west of the city, and sat there drinking a beer (my first in weeks) and smoking a cigarette. My mind still hummed the repetitious song fragment that the Honda had drummed steadily for the two days since we had left Ankara: “You can’t go back to Con-stan-ti-no-ple” over and endlessly. The late gray September Mediterranean lapped quietly against the beach; battered and dirty, the Honda silhouetted itself against the rising darkness in the east.

“18,000 and how many miles are behind me?” I muttered to myself, suddenly conscious of my voice and the presence of others.

“Too long alone,” my mind reiterated.

I reached into the wooden and fiberglass pannier for my journal, carefully wrapped in plastic, in its proper place. A quick bit of addition and I entered “Istanbul—18,843.” When I replaced it, I scrunched myself comfortably into the sand and leaned back against the pannier.

As I pulled long on that icy bottle of beer, two thoughts blundered into my mind simultaneously: the wild party Jack Smith, Greg Koval and I planned when we reached Europe, and a more sobering remembrance of the 20 hours I lay huddled behind the Honda in my sleeping bag, using a poncho for a windbreak in a blinding, choking dust storm that eventually deposited a dune a foot high over the end of the bag.

I quaffed off the remainder of the beer and decided that just because I was the only one present of the starting three, that was absolutely no reason for missing a party. With resolve I strode to the office and bought a bottle of burgundy. I meditated only a moment and purchased another.

Back at the tent I cracked the first, swilled deep from it and let out what I thought to be a jubilant “Yaaaaa Hoooo.” By the looks on the other campers’ faces, it must have soured more like the death rattle of an ancWR bull. I grinned self-consciously, took another sip, and let my mind relax. It began to wander over the preceding eight months.

Fade In: Focus on a winding, narrow paved road slicing the green jungle near Sentul, Malaya, and three blokes on nearly-identical Honda Dream 305s, riding fast and in file, enjoying the ride. Enter onto an abrupt curve, a log truck filling the road completely. Jack, in the lead, hit hard when he lost it dodging into the thick grass bordering the road. I was riding second and had a little more time, but I hit mud, felt it going and leaped clear, landing fairly hard on the pavement. From my prone position I glanced back quickly, expecting to see Greg laughing at us. He was in the road trying to get to his knees, crash hat crammed over his eyes, amaz stunned.

It was a strike for the bloody trucky, who kept on rolling. Angry, rude gestures followed him. We had to get Jack’s handlebars welded. And that night we slept in a Hindu temple down the road where candlelit garlanded Hindu gods flickered all night. Near there we also met a Chinese named Kim Swee, which means “Golden Water.” Fade Out: jtockles and grins. Temerloh, Kuantan, •Rtul, Jerantut, Kuala Lumpur, Cameron Highlands, and Penang rolled by quickly on the excellent roads of Malaya.

Taking another measured sip of burgundy, I found that the gray evening and gentle swish of the Med triggered in my mind a gray spongy day on the island of Bhuket off the west coast of Thailand. Here we watched men dive from tripods of poles rising from the picturesque bay, bringing up buckets of sand.

On the beach, Chinese women, young and beautiful, old and haggard, panned and sluiced the free tin from the sand. In back of the diggings was a stall with a set of balance scales where a heavy-jowled man bought the tin.

And then, bad, bad chuckholed dirt and graveled roads took us to Ranong en the police chief, Major Chackra, ted us to spend the night. I remem bend well how his two lovely and graceful daughters danced for our enter tainment. And it was a little way be yond Ranong where the Honda and 1 parted ways in deep, graded red dirt. I had to wait for my handlebars to be~ welded that time. We rolled on thr ,h Chumpon (memories of sinister e ts there) and Hua Hin on the Gulf of Thailand, where we stayed in the Naval Barracks. A brief stop in Bangkok, then on to Sakao and into Siem Reap, Cambodia and the ancient, fascinating ruins of Angkor Wat.

The afterglow of the sunset seemed to hold back the darkness across the Bosporus. That reminded me of how quickly night comes to the jungle. As we walked through the darkness toward Angkor, the main temple, the drums manipulated the undulations of the oboe-like flutes, and it seemed we were approaching a pagan rite.

We never spoke as we crossed the moat and entered the outer wall. Slicing spotlights focused on the front of the wat (temple), and we could see the gold and red spangled costumes and spired symmetrical headdresses of the dan Wealthy tourists sat on a platfor i front of them. In response to a modern rite, we refused to pay the 210 rials ($10) for the platform seats and chose rather to stand with the native Khmers (Cambodians).

The band, smiling and laughing at the foreigners on the ground, saw that I wanted photographs. They motioned for me to climb the wall and sit with tl^ga. With cheering from the mob and awid from the band, I scratched my way up and on top. Beautifully, exquisitely, superbly, gracefully, the girls danced, isolated from my viewpoint against the black sky.

When the two pretty girls in the jeep pulled into the campsite next to mine, my mind drifted towards Chieng Mai in northern Thailand and the graciousness of the hospitable Thais. At Kampangpetch, the police major found his barracks much too dirty for us, so he put us up in the local hotel—with showers no less—gratis.

Across the mountain to Chieng Mai, 180 of the 220 miles were dirt with thick palls of bull dust, corrugations, rocks and holes. The old Honda really caught hell, but the ride was worth it. In Chieng Mai are the most beautiful girls in the world. I fell in love three, maybe times...the first day.

^^)n the return to Bangkok, Greg lost it on rainslick pavement—two cracked ribs. Bangkok Belly (dysentery) struck hard, but how could we have contracted it? The Mekong whiskey was excellent and pure, but the ice to cool it was made from klong (canal) water, and an eighth-of-an-inch of sediment in the bottom of the glass provided the clue. The traffic in Bangkok struck fear in all of us. We saw three serious motorcycle/ auto collisions in one day, and Jack hit a car that pulled out in front of him. Only scratches were sustained by both.

Overstaying our time limit in Thailand, we had to ship the bikes by train to the Malayan border in order to get them aboard the Madras (India) bound boat in time. At 3:00 a.m. Greg and I got out of the train at Chumpon for chi dam yen (sweet tea). Back on the train and rolling, I discovered my wallet missing. My passport, international shot card, travellers cheques, and some $150 in currencies, all gone. I could not leave Thailand; I’d have to retake all of those shots. How long would it take?

In Songkhla I got a temporary travel permit from the police, and I paid a man $10 to ride the Honda to Penang with Greg to ship it. After telegraphing home for emergency money to see me through, I got back on the train and stayed mesmerized all the way to Bangkok. I had already prepared my tale of woe for the Consul, but upon arrival at the American Embassy I found I had a note from the station master at Chumpon: “Wallet found—identify

contents.” Wildly exuberant, I raced back to the station, impatiently rode back to Chumpon, tried my best to reward the station master, and rode back to Bangkok the next day with my wallet tucked carefully in my front pocket, my hand on top of it. Was it stolen or did I lose it? I don’t know. I had a strong cloth case made for the wallet that hangs around my neck. There it can’t be lost, and if it is stolen, I assume I won’t care.

I sipped burgundy and nibbled some cheese and watched the brunette remove the valve cover from the gold jeep. The color returned me to Burma. Sunrise silhouetted and enriched the huge golden Shewgoda Pagoda as we returned from the Victorian-style Strand Hotel to the Rangoon Airport.

There were lots of red buntings along the earless road, and at the airport, machine-gun-armed troops were everywhere. A red carpet led to a nearby airliner, and near it in rank and file stood about 80 of the local party, chanting in unison and waving various Communist flags.

Waiting to leave on our plane were several farang (foreigners), including three Irish nuns who were being expelled to eliminate the “Western Influence.” From them we discovered that the departing dignitary was no one less> than Chinese Premier Chou En-lai.

I quickly put on my telephoto lens and moved to the forefront to get some shots. Before I could compose one photo, I was sharply prodded in the back. Turning belligerently around, I found a soldier with the prod, a machine gun, who shook his head “no.” I “quick smart” nodded in agreement and returned to a seat, meditating about the “wrong end” of a gun.

I watched in amazement while the brunette adjusted the noisy tappets in the jeep and they returned my mind to India. Clickety-clacking south from Calcutta on the Madras Mail, glad we hadn’t purchased tickets in the overcrowded third class, we anticipated the Hondas and awaited the freedom of travel and solitude they represented. As there were no dining cars, meals were ordered early, and the orders telegraphed ahead.

About 8:00 p.m., a piping hot curry with rice served on banana leaves was brought to the seats. There was no silverware, and we grinned nervously at each other as we began to imitate the Indians and eat with our fingers. No sooner had we begun when absolute silence, then sharp whispering, caused us to look around. All eyes were upon us; some were even peeking over the seat backs. We stared at each other and around the car. What had we done?

An older gentleman took pity on us and explained. We had eaten with our dirty left hand. Horrors! Our eyes glanced down at the offending left hands, sticky with curry and rice. We had committed a very gauche social error (not necessarily the first and assuredly not the last). In a clipped British accent he stated, “The right hand is used to eat with; the left hand is used to clean yourself with.”

He nodded; we thanked him, and he returned to the gossiping, gesturing mob. We had already discovered that if one desired toilet paper, one had to bring his own, and here we learned to respect the customs of the East.

The brunette next removed a spark plug and inserted a spark plug pump which she had attached to the tent. It began to inflate when she revved the rough-running engine, firing only on three cylinders. Mind-slide to Madras. Damn, but it felt good to ease the power on the Honda, to feel the rush of speed-cooled air on my face, the vibrations on my legs, to hear the effective rumble of the exhaust. But the joy was short-lived and replaced by worry.

Upon leaving Madras, Greg disappeared. Jack and I waited and searched for him, and then we drove or^fc) Bangalore where we stayed in YMCA as planned. From there we called the American Consul in Madras, searched the hotels, worried, fretted, and after two days in the beautiful cool hill country, we departed for the north, leaving a message with our itinerary.

In Hyderabad we discovered that Greg had passed through the day before and had stayed at the Taj Hotel. The next day in Nagpur we unexpectedly found him—in the Tamashal Hospital with bad bruises and facial abrasions; ugly. He hadn’t slowed down and moved to the side of the road for an oncoming truck, and it forced him off the one lane of pavement into the deep dust and ruts of the shoulder at about 40 miles per hour.

His crash hat saved him; nothing saved his Honda; the entire front end was ruined. We loaded it onto the trj^fc and shipped it to Delhi for him. Fr^n there he had to ship it to Bombay and then on to London to satisfy the requirements of the Carnet de Passages en Douanes. This effectively ended Greg’s Asian adventures.

The whole campsite turned toward the VW camper when the German couple started screaming at each other. That reminded me of a stranger incident Jack and I watched in central India. We ^P*e sitting beneath a palm tree at one of our 50-mile rest stops. Shouting and gesturing at one another, a couple strode down the middle of the deserted road.

Suddenly she, quite angry, dropped the child, about 18 months old, in the road and headed out into the desert. Shaking his fist, still shouting at her, the man finally picked up the screaming child and muttering to himself, walked slowly out of sight, soothing the child. Who had won what?

We turned down the GT (Grand Trunk) Road, and cautiously, carefully (five head-on collisions between trucks we saw in two days), we rode to Calcutta to get our Nepalese visas. Happy to retreat from the hot humidity and humanity of Calcutta, we stayed only one day and then headed for Nepal back roads to avoid the ox carts, Wirk gangs, pedestrians, lorries and trucks of the GT. Naimpur, Dumka, Bhaglapur, Mokema, Muzzferapur, Motahari fell behind us quickly as we headed for the sanctuary of the mountains.

Jewel of the Himalayas, delight to the eye, Nepal tucked me away into its mountain womb. What a road, such a ride, winding up and over the 8100 foot pass and down into the terraced Katmandu Valley, glowing gold and bronze-green in the evening sun. Smiling, friendly people waved to us zipping along.

We quickly settled into the Tourist Corner, forsaking the cheaper Globe for the comfort of a shower, and headed to the Blue Tibetan where we ate buffalo chow chow. Real red meat for the first time in weeks and a treat it was. So good did it taste, it took me several meals to recognize that the water buffalo was tough and stringy.

Having grown up in the mountains of Wyoming and being decidedly homesick for mountains, I chose to stay and explore Nepal. So Jack and I bid farewell to each other after nine days in Nepal. He headed back to India and on to Europe. I began a furtive trek to Nam Che Basar with a Norwegian girl that ended in dysentery and a hospital for her.

Darkness settled over Mocamp; the automatic camp lights came on and kindled a scene that has returned to my mind time and again. Sunlight died slowly, changing the ancient gray stones from warm to cold, unfeeling, impersonal. The nearly-full moon reflected luminously in the Bagmati River, a tributary of the Hindu’s Holy River Ganges, which runs through Pasupathinath Temple.

When Reidun, my Norwegian friend, and I first saw the body, it was on a ghat in front of the main temple, wrapped in a gold patterned red cloth, a woman. At head and feet oil lamps burned to light the soul’s journey. After being anointed with burned straw and oil mixture, the body was placed on a bamboo litter and carried to the carefully stacked pyre.

Jerking sobs and renting moans came from the temple, as her husband was led to the ghat, a white sarong around his waist, a white bandana across the back of his gray head. A bell began pounding, ringing quickly and steadily; suddenly it ended. After being carried around the pyre three times, she was placed on it, her head and body on top, her legs drooping to the stone.

The relatives washed in the Holy Bagmati and symbolically washed the body twice. Finally, amid wails, the husband was led to wash himself and then around the pyre three times to symbolically cleanse the body. A firebrand was given to him, and he was led around again two times; on the^prd circuit he ignited the pyre, wailing and sobbing so that it seemed to stifle the flickering flames.

(Continued on page 104)

Continued from page 73

He washed again and was led away by his relatives. The tenders began to stoke the fire and the yellow flames rose. In the river the reflection flickered; it brightened as the clothes caught. Then the crackling of the body feeding its own fire began to dominate. Ashes to ashes.

The two girls, their magic tent completely inflated, and I watched in amusement as two brothers, about eight or so, tried to catch their escaped poodle. We grinned at each other.

I remembered one early bright May morning while I was taking tea and toast on the porch of Tourist Corner. Whom should I see approaching through the courtyard but Fritz, gibbon on leading several luggage-laden porterSmd an entourage of kids clamoring about the small ape. I knew Fritz from Penang where he was the artiste-in-residence and where Murphy, the gibbon, ceaselessly entertained all. He loved to chase birds—and even their shadows.

Fritz had smuggled him out of Thailand by tranquilizing him and wrapping him to his arm and then slinging it as if it were broken. In the Bangkok Airport, while buying a magazine, he noticed the saleslady staring in horror at his arm. Glancing down at the “broken arm,” he saw Murphy’s tiny, hairy paw poking through the bandage, grasping and clutching. Needless to say, Fritz went to the bathroom in a hurry.

While being smuggled through Howrah Station in Calcutta, Murphy nearly died of strangulation when he got^angled in his leash inside of Fritz’s sa^^l. Fritz barely saved him by mouth to mouth resuscitation. Though Murphy lived, this close conference with death so changed his personality, demeanor and carriage (he even ran from birds), that Fritz had re-christened him Lazarus. “Lazarus,” I often questioned him, was the risin’ worth it?”

Sober thoughts returned when I remembered Benares, India. There I recall an old man, naked except for a string around his waist, who moved in a crouch on the flats of his feet and hands, ape-like, digging through the gutter rubbish for food. Children played noisily nearby, food shops sold, men walked past...I rode by.

As I finished the first bottle of wine, my mind hurried quickly through the heat from Delhi to Bombay, the boat ride on the Sirdhana to Karachi, stan, and the blistering heat fron^^e Rann of Kutch to Peshawar.

A friendly druggist who rode a Vespa introduced me to Peshawar. H^Ä>efriended me and stood me to meals and a hotel room for two days. His father had recently died at the age of 120 years after four wives, 20 sons, and 15 daughters. The druggist himself had two wives. He arranged for me to take pictures of the Kohat-Darra Tribal Arms Factory. Northwest Pakistan is not actually controlled by the Pakistani government; it is governed and administered by the various tribes in the area.

(Continued on page 106)

Continued from page 104

I followed my friends on the Vespa to Kohat, a small village of adobe businesses scattered along a single street. Most of these sell firearms, from pen pistols to machine guns. All of the guns are handmade. There is no electricity, and lathes, drills, etc. are handdriven using cranks and pulleys.

In a courtyard, the master gunsmith oversaw barrels being rifled by ha^l. Elsewhere bullets are manufactured®«! cartridges loaded. Periodically, shots rang out as the weapons were tested or demonstrated for prospective customers. No questions asked.

On the north side of Kohat is a small building where their well-known black hashish is produced. Goat skins full of the tender leaves and flowering tops of marijuana plants were stacked in a corner. Two men used their weight to rhythmically counterbalance a heavy beam tipped at right angles with a metal plunger. A third man pushed the marijuana into a hole where the plunger crushed it into a mold. Soles of hashish, the finished product, were drying in rows.

We stayed only a short time because my two guides, Pakistanis from Peshawar, were very nervous around these armed, fierce-looking, indepen^Ät, gray-eyed Pushtanis.

Listening to the two English girls chatter as they cooked their tea (evening meal) on the tailgate of the jeep, brought me to remember Maureen, a delightful Canadian nurse I met in Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan. She joined me in a journey to central Afghanistan to see Bamiyan and Band-iAmir. A pretty fair dirt road took us to the large valley, irrigated and green, ordered by rows of tall poplar trees, an impressive sight in that barren treeless region.

On the north side of the Bamiyan valley is a huge sandstone cliff, tan; and in the cliff are two giant Buddhas and hundreds of small caves in which the monks lived. These were carved while they worked and learned here between the First and Sixth Centuries A.D. T^ie largest Buddha is 83 meters high, ai^p; provides an exhilarating climb and a fantastic view from the top of the head.

(Continued on page 108)

Continued from page 106

The smaller is only 45 meters tall. At one time they were both frescoed and painted in bright colors; remnants can still be seen above the head of the large one.

Seventy-nine miles of miserable rough gravel roads and steep switchbacks led us to the high treeless plains and Band-i-Amir Lakes. Old Honda really strained and gasped under the double load and in that thin air. Deep in the eroded center of the plateau we found the lakes shimmering blue, indelible, infinite. And how well I remember the return over Hajigak Pass, more than 10,000 feet.

Two big koochi (sheepherders’) dogs, complete with spiked collars to protect them from leopards, waited for us on a switchback above us. They knew we had to come by them, and when we did, chase us they did. Luckily they were content to chase and bark only, as we could barely outrun them.

As we neared the asphalt, after several days on the bad dirt, I became tired and careless. A small band of sheep broke across the road in front of me while I was making around 20 mph. The first few made it; the last didn’t. We went down in heavy gravel. Maureen rolled clear and I skinned up my arm and shoulder. The sheep had at least one broken leg and appeared to have only a short time left in this world.

Old Honda suffered a dinged fender, broken headlight and mirror, and numerous scratches. While surveying the damages, a commercial truck stopped and the driver pointed across the flats towards a koochi tent. “Burro, burro'.” (Hurry, hurry!), he shouted and drove off. Across the flats came the koochi at a run. I started the Honda, and we literally jumped on. The gear lever, I found, was also bent, and I could only get second gear.

We were leaving slowly and the koochi was so close he was trying to grab Maureen. Falling slightly behind, he tried to hit us with his staff. Maureen kept repeating a litany of “Faster Jerry, faster,” pushing me forward on the seat. He finally threw his staff at us; it missed and we escaped. Had the sheep died (probable) and was found to be an ewe, we would have had to pay for all its estimated future offspring. Had it been a ram—I still can’t bear to think of it.

The second bottle of wine was well opened and the near past began flooding my mind. The Long Drop Hotel was closed in Kabul while I was there. Officially known as the Jade de Maiwand, it had no bathing facilities and the toilet was a hole in the floor on the third story. Hence, the name. Then I moved to the Nawazish, called the Neverwash, a definite misnomer because it had a shower and a toilet.

Mazar-i-Sharif, near the Russian border, that was where the steering column bearings gave out completely. With resignation I crippled back across the beautiful Salang Pass where the Russian Highway tunnels through the formidable Hindu Kush Mountains. In the freezing tunnel, over 11,000 feet high, I ran out of gas. Luck was with me and I was on the downhill side; I coasted to the petrol depot in Charikar. Fantastically, in Kabul I found a used set of bearings and races for the front end, and I pushed quickly from Nargar and flew past Kandahar, Girsht on to Herat on the American Friendship Highway.

Bandit-bandana-covered face, dirt blowing, dirt sifting, dust-filled holes in dirt roads; body and Honda perpetually encrusted with dirt. Dirt dusted me over and covered me under. Hidden behind the Honda for 20 hours waiting to be able to see. Old Honda labored with bad plugs (my spares), valves rattled, but it was too dirty to open up to adjust them, bad mileage, front end bearings grooved and beaten out again.

Nan and chi (bread and tea) for breakfast; harbuza (honeydew melon) for lunch; nan and chi for dinner. I had overstayed and overspent in Afghanistan and had to sell my binoculars and movie camera to get to Tehran.

The needle valve vibrated loose near Faizabad, Iran and choked off my fuel. An English acquaintance happened by in the middle of the Never-Never and helped me solve that problem. More luck. And to get into Iran I had to take eight horse-sized pills for cholera, even though I had a valid shot card. The miserable health official even made me open my mouth and then inspected it with a flashlight to see if I had swallowed them.

Customs tore my entire pack and panniers apart searching for that evil Afghani hashish. I had to walk all over Faizabad getting clearance signatures from the police, the army, the secret police ad infinitum. From 3:00 p.m. until 9:30 it took me to clear the border. Worst crossing I have ever had. Still bitter.

Tehran on September 6 and mail. I picked up the first mail since Delhi back in June. I carefully stacked the two months mail according to writer and especially to date, in anticipation of bad news: none.

Honda of Tehran, of course, had nothing for 305s, but they manufactured races for the steering column and fitted bearings to them. They tuned, repaired, welded racks (for the nth time,

I lost track), and charged for service and labor only. Cholera sealed off Iraq and put the quietus on any tour of the Middle East as planned. However, a note from Jack, already in Ireland, stated that he had made the Middle East leg. Cold nights, snappy mornings; fall was here and harvests were happening everywhere. Had to wear my ski parka all day.

(Continued on page 110)

Continued from page 109

Wake up; watch the sunrise; take 20 winks; break camp and pack the tent with dew on it. Ride quickly to the closest town for tea and bread. Push on, push, push, rest break now every 75 miles. Eat lunch when stomach demands it; calculate miles to Turkey’s border.

My mind wanders, wonders where to winter: London, friends; Germany,

friends; mountains, better. Watching the ducks mass for migration, I would like to hunt. Reminds me of my goose hunting buddy in Bountiful. I remember awhile.

Ride; stop, must take photo; light not right. Ride; should have taken that picture. Stop; take picture. Ride, terrible picture. Always eat in the evening at the last possible town. Ride, good campsite, no, too early. Ride, ride; too late; take any campsite. Up with the tent, still wet from morning dew, be wetter in the morning; blow up air mattress, still leaking; write note to self, “fix air mattress.” Light candle; begin communication with my friend (my journal), slow, deliberate, printed mind messages. Blow out candle; stare at ridge pole until sleep. Wake; watch sunrise; catch 20....

Turkey finally and I spoke English to a Dane at the border; it felt strange and I wanted to talk more. Gray day, drizzle, snowing on Mount Ararat where the supposed ark reposes in ice. I stopped and put on all of my clothes, worried about my freezing fingers. Seventy miles I hurried towards Agri and finally got there after dark. I was so cold that it was a necessity to rent a hotel room, not a luxury. There was no hot water, so I crawled into bed to get warm and then got up and ate.

My pragmatic mind says, “You’re not seeing all there is to see.”

“What the hell difference does it make?” my gut reaction answers.

“What about your plans? You’re only here once!”

“So what? Push for London,” gut says.

“No, Ernst, the Swiss photographer, said Goerme is fantastic,” practical insisted.

“Push for London.”

“Lots warmer in southern Turkey; Goerme is on the way.”

“Warmer, warmer; south and then quickly to London, okay,” decides gut.

“Okay.”

Two days in Goerme, the City of 1000 Churches, and I lay in the shade of grape arbors, plucking juicy grapes. I> explored the many “churches,” actually rooms hollowed into the soft rock, admiring the remnants of the Christian frescoes, painted in the dark black rooms with the aid of reflected light.

I watched a Spanish company filming a movie and began to see color and form again. I actually planned and executed several photos. Still there was no one to talk with, no one to share the finds with. My emotions overruled my mind and I decided to push for London, friends there and a job.

“Besides, it’s getting cold up north.”

“No need to rationalize!”

My gawd, an excruciatingly beautiful and marvelous experience I had. Hot, hot and wet, the fantastic aroma penetrated my being and the vision filled the whole room. Oh, it was good! In Ankara I had my first hot shower since Rangoon back exactly on April 19, five bloody months before. No more dirt roads, a celebration scrubbing.

I returned mentally to my physical being, still at Mocamp. My courage bolstered via the Dutch method, I estimated the remainder of the bottle and sauntered over to the girls’ tidy campsite, clutching the neck of the bottle. None of the quickly rehearsed suave lines emerged from my lips.

“How—how—how dya like a drink where you headed nice jeep nice tent you have there,” gurgled from my mouth like water from a jug.

“That would be nice,” the taller replied, grinning.

“India, thank you, thanks, in that order,” she answered.

We divided the bottle equally and slowly began talking about Asia. Well into the next bottle and way into the night, the stored words and unshared memories began to flood, to deluge out, an almost physical relief to free them.