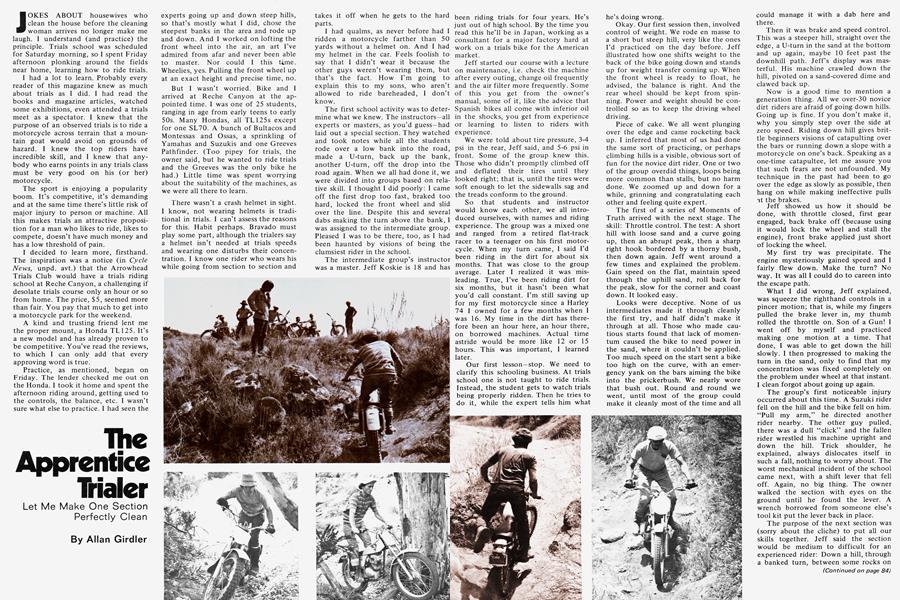

The Apprentice Trialer

Let Me Make One Section Perfectly Clean

Allan Girdler

JOKES ABOUT housewives who clean the house before the cleaning woman arrives no longer make me laugh. I understand (and practice) the principle. Trials school was scheduled for Saturday morning, so I spent Friday afternoon plonking around the fields near home, learning how to ride trials.

I had a lot to learn. Probably every reader of this magazine knew as much about trials as I did. I had read the books and magazine articles, watched some exhibitions, even attended a trials meet as a spectator. I knew that the purpose of an observed trials is to ride a motorcycle across terrain that a mountain goat would avoid on grounds of hazard. I knew the top riders have incredible skill, and I knew that anybody who earns points in any trials class must be very good on his (or her) motorcycle.

The sport is enjoying a popularity boom. It’s competitive, it’s demanding and at the same time there’s little risk of major injury to person or machine. All this makes trials an attractive proposition for a man who likes to ride, likes to compete, doesn’t have much money and has a low threshold of pain.

I decided to learn more, firsthand. The inspiration was a notice (in Cycle News, unpd. avt.) that the Arrowhead Trials Club would have a trials riding school at Reche Canyon, a challenging if desolate trials course only an hour or so from home. The price, $5, seemed more than fair. You pay that much to get into a motorcycle park for the weekend.

A kind and trusting friend lent me the proper mount, a Honda TL125. It’s a new model and has already proven to be competitive. You’ve read the reviews, to which I can only add that every approving word is true.

Practice, as mentioned, began on Friday. The lender checked me out on the Honda. I took it home and spent the afternoon riding around, getting used to the controls, the balance, etc. I wasn’t sure what else to practice. I had seen the experts going up and down steep hills, so that’s mostly what I did, chose the steepest banks in the area and rode up and down. And 1 worked on lofting the front wheel into the air, an art I’ve admired from afar and never been able to master. Nor could I this time. Wheelies, yes. Pulling the front wheel up at an exact height and precise time, no.

But I wasn’t worried. Bike and I arrived at Reche Canyon at the appointed time. I was one of 25 students, ranging in age from early teens to early 50s. Many Hondas, all TL125s except for one SL70. A bunch of Bultacos and Montessas and Ossas, a sprinkling of Yamahas and Suzukis and one Greeves Pathfinder. (Too pipey for trials, the owner said, but he wanted to ride trials and the Greeves was the only bike he had.) Little time was spent worrying about the suitability of the machines, as we were all there to learn.

There wasn’t a crash helmet in sight. I know, not wearing helmets is traditional in trials. I can’t assess the reasons for this. Habit perhaps. Bravado must play some part, although the trialers say a helmet isn’t needed at trials speeds and wearing one disturbs their concentration. I know one rider who wears his while going from section to section and takes it off when he gets to the hard parts.

I had qualms, as never before had I ridden a motorcycle farther than 50 yards without a helmet on. And I had my helmet in the car. Feels foolish to say that I didn’t wear it because the other guys weren’t wearing them, but that’s the fact. How I’m going to explain this to my sons, who aren’t allowed to ride bareheaded, I don’t know.

The first school activity was to determine what we knew. The instructors—all experts or masters, as you’d guess—had laid out a special section. They watched and took notes while all the students rode over a low bank into the road, made a U-turn, back up the bank, another U-turn, off the drop into the road again. When we all had done it, we were divided into groups based on relative skill. I thought I did poorly: I came off the first drop too fast, braked too hard, locked the front wheel and slid over the line. Despite this and several dabs making the turn above the bank, I was assigned to the intermediate group. Pleased I was to be there, too, as I had been haunted by visions of being the clumsiest rider in the school.

The intermediate group’s instructor was a master. Jeff Koskie is 18 and has been riding trials for four years. He’s just out of high school. By the time you read this he’ll be in Japan, working as a consultant for a major factory hard at work on a trials bike for the American market.

Jeff started our course with a lecture on maintenance, i.e. check the machine after every outing, change oil frequently and the air filter more frequently. Some of this you get from the owner’s manual, some of it, like the advice that Spanish bikes all come with inferior oil in the shocks, you get from experience or learning to listen to riders with experience.

We were told about tire pressure, 3-4 psi in the rear, Jeff said, and 5-6 psi in front. Some of the group knew this. Those who didn’t promptly climbed off and deflated their tires until they looked right; that is, until the tires were soft enough to let the sidewalls sag and the treads conform to the ground.

So that students and instructor would know each other, we all introduced ourselves, with names and riding experience. The group was a mixed one and ranged from a retired flat-track racer to a teenager on his first motorcycle. When my turn came, I said I’d been riding in the dirt for about six months. That was close to the group average. Later I realized it was misleading. True, I’ve been riding dirt for six months, but it hasn’t been what you’d call constant. I’m still saving up for my first motorcycle since a Harley 74 I owned for a few months when I was 16. My time in the dirt has therefore been an hour here, an hour there, on borrowed machines. Actual time astride would be more like 12 or 15 hours. This was important, I learned later.

Our first lesson—stop. We need to clarify this schooling business. At trials school one is not taught to ride trials. Instead, the student gets to watch trials being properly ridden. Then he tries to do it, while the expert tells him what he’s doing wrong.

Okay. Our first session then, involved control of weight. We rode en masse to a short but steep hill, very like the ones I’d practiced on the day before. Jeff illustrated how one shifts weight to the back of the bike going down and stands up for weight transfer coming up. When the front wheel is ready to float, he advised, the balance is right. And the rear wheel should be kept from spinning. Power and weight should be controlled so as to keep the driving wheel driving.

Piece of cake. We all went plunging over the edge and came rocketing back up. I inferred that most of us had done the same sort of practicing, or perhaps climbing hills is a visible, obvious sort of fun for the novice dirt rider. One or two of the group overdid things, loops being more common than stalls, but no harm done. We zoomed up and down for a while, grinning and congratulating each other and feeling quite expert.

The first of a series of Moments of Truth arrived with the next stage. The skill: Throttle control. The test: A short hill with loose sand and a curve going up, then an abrupt peak, then a sharp right hook bordered by a thorny bush, then down again. Jeff went around a few times and explained the problem. Gain speed on the flat, maintain speed through the uphill sand, roll back for the peak, slow for the corner and coast down. It looked easy.

Looks were deceptive. None of us intermediates made it through cleanly the first try, and half didn’t make it through at all. Those who made cautious starts found that lack of momentum caused the bike to need power in the sand, where it couldn’t be applied. Too much speed on the start sent a bike too high on the curve, with an emergency yank on the bars aiming the bike into the prickerbush. We nearly wore that bush out. Round and round we went, until most of the group could make it cleanly most of the time and all could manage it with a dab here and there.

Then it was brake and speed control. This was a steeper hill, straight over the edge, a U-turn in the sand at the bottom and up again, maybe 10 feet past the downhill path. Jeff’s display was masterful. His machine crawled down the hill, pivoted on a sand-covered dime and clawed back up.

Now is a good time to mention a generation thing. All we over-30 novice dirt riders are afraid of going down hills. Going up is fine. If you don’t make it. why you simply step over the side at zero speed. Riding down hill gives brittle beginners visions of catapulting over the bars or running down a slope with a motorcycle on one’s back. Speaking as a one-time catapultée, let me assure you that such fears are not unfounded. My technique in the past had been to go over the edge as slowly as possible, then hang on while making ineffective pulls at the brakes.

Jeff showed us how it should be done, with throttle closed, first gear engaged, back brake off (because using it would lock the wheel and stall the engine), front brake applied just short of locking the wheel.

My first try was precipitate. The engine mysteriously gained speed and I fairly flew down. Make the turn? No way. It was all I could do to careen into the escape path.

What I did wrong, Jeff explained, was squeeze the righthand controls in a pincer motion; that is, while my fingers pulled the brake lever in, my thumb rolled the throttle on. Son of a Gun! I went off by myself and practiced making one motion at a time. That done, I was able to get down the hill slowly. I then progressed to making the turn in the sand, only to find that my concentration was fixed completely on the problem under wheel at that instant. I clean forgot about going up again.

The group’s first noticeable injury occurred about this time. A Suzuki rider fell on the hill and the bike fell on him. “Pull my arm,” he directed another rider nearby. The other guy pulled, there was a dull “click” and the fallen rider wrestled his machine upright and down the hill. Trick shoulder, he explained, always dislocates itself in such a fall, nothing to worry about. The worst mechanical incident of the school came next, with a shift lever that fell off. Again, no big thing. The owner walked the section with eyes on the ground until he found the lever. A wrench borrowed from someone else’s tool kit put the lever back in place.

The purpose of the next section was (sorry about the cliche) to put all our skills together. Jeff said the section would be medium to difficult for an experienced rider: Down a hill, through a banked turn, between some rocks on an upgrade, over a step and across a dirt road, down into the ravine again, paraltel to a sewer pipe, over some rocks and back onto the road.

(Continued on page 84)

Continued from page 82

This was our chance to use all the basics we’d been practicing. As you may have gathered (and I didn’t realize until later) the early work involved one problem at a time, each with its proper technique. Then we used them one after the other. Now we had reached the stage—it was hoped—of using them all at once.

I had my first fall of the school. Not too bad, as falls go. I came down the hill too fast (again!) and went up the bank too high. Turning to get down caused me and machine to fall over, on the brake lever and my right thumb, both of which bent. I carried on despite.

There were more important things to think about. I reckon trials is like any physical skill, in that events happen too quickly for the novice mind. If your head tells you the surfboard is tipping, it’s too late. If your head tells your hands the race car is traveling sideways, ditto. Trained instinct is the only answer.

I didn’t have trained instinct. I had to think about every inch of that descent, which meant I was in the wrong place and at the wrong angle when I came to the turn. Wobble through that and there was the path through the rocks, two feet to the right of my front wheel.

What I had was untrained instinct. By this time I had learned to not grab the clutch. I had learned how to work the front brake and the throttle separately. But while I knew I should be standing on the pegs, using my weight to balance and aim the bike, at the first sign of trouble I sat down and began to paddle. Wrong, wrong, wrong. I managed to get through the section, but only by dabbing every foot of the way.

Speaking of human frailty, the differences in intermediateship began to reveal themselves in this section. The precise riders, the ones who could put their bikes on the exact desired line, did fine here. The others, that is, the rest of us, had trouble. One guy lost his temper and declared it was the fault of the bike. It would not do the section correctly due to some obscure design flaw, he said. Rather than argue, Jeff borrowed the thing and went through clean as a whistle. Good teaching psychology? Probably not. Made the poor devil feel foolish and no teacher likes to do that. But the pupil did learn something. So did the rest of the group. That was the last time anybody complained about his mount.

(Continued on page 114)

Continued from page 84

We moved to a precision section. This was a dry stream bed, nearly level and with good grip, but very narrow. There was only one way through.

Jeff stood to one side in the middle of the section. I eased into the slot and was bumping along, rather pleased that I hadn’t put my foot down yet, when I passed him. “Tighten up,” he shouted.

What did he mean by that? I pondered this while waiting in line for my next turn. Flash! Surely! The bike was flopping around as I tried to aim it and I was flopping after it. All my energy and effort was directed at staying aboard. The bike was the dog and I was the tail. To tighten up would be to resist the bike’s attempts to deflect itself from the proper line. I tried doing that. At the same time I made great mental effort toward keeping my feet up. With not too much success, alas. This must be something that comes only with practice. Until this event I had spent a lifetime balancing myself with my feet on the ground. If I stumble, I put out a foot and catch myself. Learning not to do this, learning to keep my feet on the pegs and lean the other way with knees and hands is a habit that will only come with many hours of practice.

But I bumped through the section more tightly than before, earning a shout of approval, and I kept my feet up until the last minute. Make every dab count, Jeff said, and only dab when the alternative is to stall or fall over. Good advice, albeit in my case I was in danger of both most of the time. I did fall once in this section. The outboard end of the gear lever struck first, on a rock. It was bent back parallel to the frame. Still worked and no great handicap as all our section riding was done in first gear.

The next section filled us intermediates with trepidation. A steel pipe was laid at an angle to the path. Then over a 6-ft. hummock, between two trees, along a leaf-covered bank, around a tree with a branch lower than our heads and across a 1 -ft. log. Our fears tripled when invincible Jeff had to dab going over the hummock.

Crossing the pipe was easier than it looked. The trick was to swing the front wheel wide, around the end of the pipe, then cut back and drag the rear wheel over. No power on, as the rear wheel would spin and crab the bike off the path to the hummock. Most of us did this fairly well. Few of us had enough momentum left to get up the hummock without using feet. Squeezing between the trees was easier than it looked and crossing the leaves was mostly a matter of tilting the machine at a right angle to the ground and putting all weight on the outside peg. Most of us went too wide around the last tree and fell into the bushes trying to avoid the low branch. Jumping the log was fun. I suspect everybody there had been practicing for 4tost such a test. Me too, even though on ^iny first try I got the front wheel up and over only to cut power so completely that the bike stalled at mid-log.

One more blow-by-blow, because it proved a point. We went to another stream bed, lined with boulders. There was a path leading to a flat rock, off of which we were supposed to jump onto the correct approach for the next rocks.

I came off the rock in the wrong place and fetched smartly up against the bank, with my leg between the bank and the exhaust pipe. Yes, the pipe was hot.

What I did wrong, Jeff said, was jump from the wrong place. I tried again and jumped from the wrong place again. In plain words, I couldn’t put the motorcycle where it was supposed to be. I was guiding it in the general

€ection only. That wasn’t good ough. All my deftness with throttle and brake, my new-found ability to shift weight and control wheelspin, all the things I had learned, were secondary to this lack of basic aim.

So it went, up and down, around and about, from one section to the next. None of us received any formal certification, say, an invitation to ride for the team. Nor did the experts tell anybody (in my group, at least) that they would be well advised to take up some other hobby.

Our group had two graduates with honors. Jeff let the retired flat-tracker and one guy with a Suzuki try his own Bultaco on the last and toughest section of the school. No hurt feelings, as they were in fact the best riders in the group. We all went home happy because we ^^d all learned a lot, far more than we’d ^ick up riding by ourselves or by entering a trials without prior exposure.

Aside from the separate skills mentioned earlier, I learned:

1) The ability to put the machine in exactly the right place is the most important thing a beginning trialer can have. To become an expert you’ll have to go far beyond this, of course, but for any trials course there’s always a best way through every section. If you can keep the bike on the best way, the fine points will come in due course.

2) You need to be at home on the bike and on your feet, that is to say, standing up on the pegs. A trials rider must completely control his bike and you can’t do it sitting down.

I said we didn’t get a formal report card. But while I was loading up for the ^■p home, Jeff said “You have a lot of skill...hampered by a man who wants to sit down.”

A lot of skill, eh? That alone was worth the $5 tuition.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

November 1973 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1973 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeedback

November 1973 -

The Scene

November 1973 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Competition

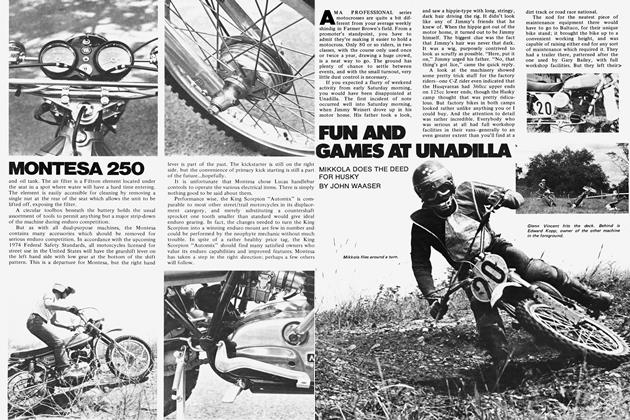

CompetitionFun And Games At Unadilla

November 1973 By John Waaser -

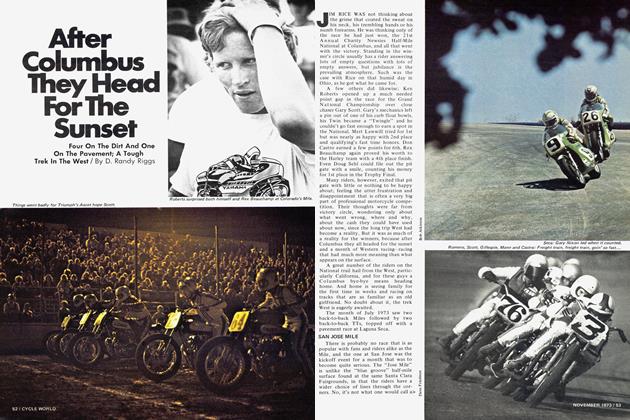

Competition

CompetitionAfter Columbus They Head For the Sunset

November 1973 By D. Randy Riggs