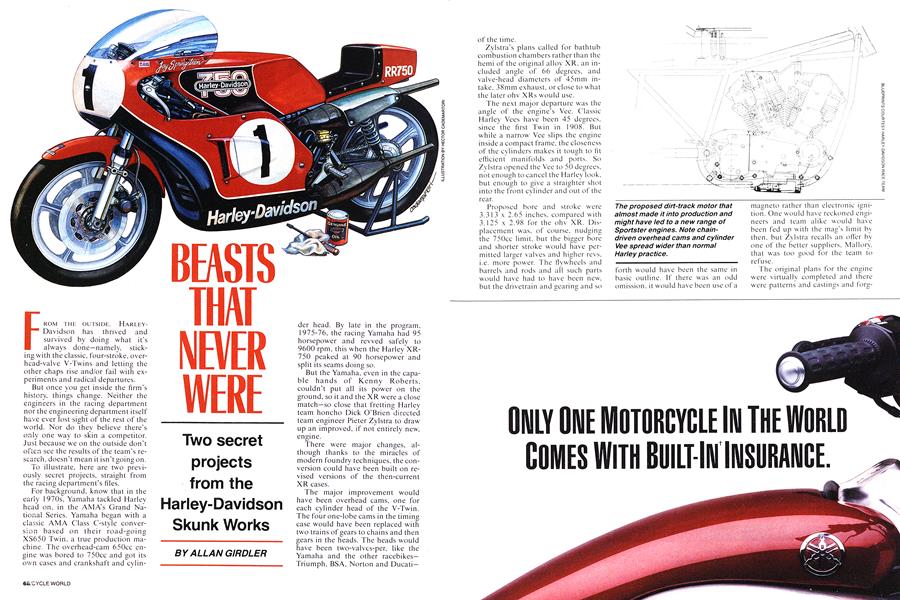

BEASTS THAT NEVER WERE

Two secret projects from the Harley-Davidson Skunk Works

ALLAN GIRDLER

FROM THE OUTSIDE. HARLEYDavidson has thrived and survived by doing what it's always done—namely, sticking with the classic, four-stroke, overhead-valve V-Twins and letting the other chaps rise and/or fail with experiments and radical departures.

But once you get inside the firm's history, things change. Neither the engineers in the racing department nor the engineering department itself have ever lost sight of the rest of the world. Nor do they believe there's only one way to skin a competitor. Just because we on the outside don't often see the results of the team’s research. doesn't mean it isn't going on.

To illustrate, here are two previously secret projects, straight from the racing department’s files.

For background, know that in the early 1970s. Yamaha tackled Harley head on, in the AMA's Grand National Series. Yamaha began with a classic AMA Class C-stvle con ver-

sion based on their road-going XS650 Twin, a true production machine. The overhead-cam 650cc engine was bored to 750cc and got its own cases and crankshaft and cylin-

der head. By late in the program, 1975-76, the racing Yamaha had 95 horsepower and revved safely to 9600 rpm, this when the Harley XR750 peaked at 90 horsepower and split its seams doing so.

But the Yamaha, even in the capable hands of Kenny Roberts, couldn’t put all its power on the ground, so it and the XR were a close match—so close that fretting Harley team honcho Dick O’Brien directed team engineer Pieter Zylstra to draw up an improved, if not entirely new, engine.

There were major changes, although thanks to the miracles of modern foundry techniques, the conversion could have been built on revised versions of the then-current XR cases.

The major improvement would have been overhead cams, one for each cylinder head of the V-Twin. The four one-lobe cams in the timing case would have been replaced with two trains of gears to chains and then gears in the heads. The heads would have been two-valves-per. like the Yamaha and the other racebikes— Triumph, BSA. Norton and Ducati — of the time.

Zylstra’s plans called for bathtub combustion chambers rather than the hemi of the original alloy XR. an included angle of 66 degrees, and valve-head diameters of 45mm intake, 38mm exhaust, or close to what the later ohv XRs would use.

The next major departure was the angle of the engine's Vee. Classic Harley Vees have been 45 degrees, since the first Twin in 1908. But while a narrow Vee slips the engine inside a compact frame, the closeness of the cylinders makes it tough to fit efficient manifolds and ports. So Zylstra opened the Vee to 50 degrees, not enough to cancel the Harley look, but enough to give a straighter shot into the front cylinder and out of the rear.

Proposed bore and stroke were 3.313 x 2.65 inches, compared with 3.125 x 2.98 for the ohv XR. Displacement was. of course, nudging the 750cc limit, but the bigger bore and shorter stroke would have permitted larger valves and higher revs, i.e. more power. The flywheels and barrels and rods and all such parts would have had to have been new, but the drivetrain and gearing and so

forth would have been the same in basic outline. If there was an odd omission, it would have been use of a

magneto rather than electronic ignition. One would have reckoned engineers and team alike would have been fed up with the mag's limit by then, but Zylstra recalls an offer by one of' the better suppliers. Mallory, that was too good for the team to refuse.

The original plans for the engine were virtually completed and there were patterns and castings and lorgings done for the heads, pistons, rods and cylinders, but the engine itself was never completed.

The second secret project followed Yamaha into the mine field of the purebred racing machine.

History again: When the AMA imposed a requirement of 200 complete motorcycles as the rule for production racing, Harley and all the other factories figured that was that. No maker was so foolish as to build that many bikes just to win races.

They didn’t figure on Yamaha’s passion to beat Harley and Honda, not to mention the rest of the world. The XS650-based 750 Twin wouldn’t quite do it. The two-stroke 35Ö Twin came close but still fell short, so Yamaha came out with the TZ700 (which quickly became a 750). It was an across-the-frame Four, two two-stroke Twins side by side, liquid-cooled and speedily recognized as the best roadracing engine there was.

The AMA quickly got even by changing the rules. Instead of 200 bikes, you needed only to produce one machine and 24 engines, thus more easily allowing other manufacturers a shot at the soon-to-be-allconquering TZ.

Harley’s team and management came up with three clear facts: ^Unless you had a 750cc two-stroke Multi, you might as well not go to the roadrace nationals; 2) you had to compete in the roadraces to win the national series; and 3) Harley-Davidson’s Italian Aermacchi subsidiary, winner of world titles in the smaller

classes, could help the home team with its very own two-stroke 750 Four roadrace bikes.

The team bought a TZ750—they were for sale to the public if you knew how to do it. just as the XR-750 was—took it home, took it apart, weighed every piece and set out to make some improvements.

The drawings reproduced here are as far as the project got.

They show a sound design, a bulge in the cutting edge, you could say. O’Brien and Greg Sassaman. the Har-

ley team rider most interested in roadracing at the time, went to visit the Aermacchi shops in 1976 and came back with what the top teams in Europe were up to. They had the TZ750. and a working knowledge of Suzuki's RG 500 square-Four, so they went from there.

Zylstra thought the Yamaha crossframe Four was too wide and

Suzuki’s upright square-Four was too high. So he laid out what amounted to a horizontal square-Four: a pair of side-by-side twins, one atop the other, all bores parallel to the ground. Each cylinder had its own crank and case. The top two and the bottom two were geared together and the pairs rotated in opposite directions. They were joined by a central primary gear, an idler gear on a long shaft that went to the left for primary drive and clutch, to the right for waterpump. tach and the other drives. There was a six-speed gearbox. Induction would be disc valve, with the four carbs outboard of their respective cylinders. The top two expansion chambers and pipes would be above the engine, the lower two below it. The engine was small and compact so the frame backbone was virtually a straight line from steering head to swingarm pivot, a feature evers designer hopes for. but few achieve.

There were some deft touches, for instance the oval frame sections and the tapered swingarm legs. The rest of the design was conventional, with disc brakes and cast. 18-inch wheels. Zylstra prudently voted to experiment with the engine and let the rest of the machine he routine, in the interests of having only one radical venture to cope with at a time.

He spent three months on the drawings and specifications, but that's as far as the project, which in Harley parlance would have been the RR-750, got. No parts were made.

Why were the two racing bikes begun and then abandoned? Surely, economics tops the list. In the late 1970s, Harley-Davidson was a subsidiary of A MF. which had saved the company from ruin, but which also expected a return on its investment. Expansion of production had hurt quality control and there were more unhappy owners than satisfied racing fans, so management trimmed the racing team’s sails.

By great good luck or perhaps not, this wasn't the disaster it would have been a few years earlier. The arrival and dominance of the Yamaha

TZ750 in grand national racing meant that the production roadracer overcame the street-based production racer on pavement. Yamahas won the roadraces, plain as that. Meanwhile, the old firms, BSA, Triumph and Norton, went out of business and the new guys, Kawasaki, Suzuki and on the fringes Honda, didn't care about dirt.

The Olympic ideal, a national champion who could win any type of race, was done for. Yamaha quit the dirt and sent Ken Roberts to whip the world, which he found easier than beating Harley and Jay Springsteen, who, in turn, was able to win the national championship without roadracing.

What we had here was a version of politics. John F. Kennedy used to joke that his rich and powerful father always told him not to buy more votes than he needed. He’d pay for an election, Kennedy said the old man vowed, but darned if he’d pay for a landslide.

Harley-Davidson management would have understood that perfectly. They were willing to pay fora national championship, but not for anything that wasn’t needed, and the XWOC-750 (an identification I invented, representing the unit twin,

wide-Vee, overhead-cam 750) and RR-750 weren't needed.

One supposes we can't even say it's a shame. For all we know, the overhead-cam XR engine would have resulted in an ohc Sportster, and a dirttracker that wouldn’t have needed a handicap against Honda’s later ohc RS750. And the Harley roadrace 750 could have given us epic nationals, Springsteen vs. Roberts, equal to the epics of Honda and Spencer against Yamaha and Roberts in the 1983-84 world'series. Equally, the new Harley tracker could have been the wretched

failure the later Virago-based Yamaha 750 fiat-track bike was, and the two-stroke Harley could have been as disastrous as the four-stroke Honda GP bike.

The only real shame is. we’ll never know. 0

Editor's Note: The preceding article was excerpted from Allan Girdler's forthcoming book "Sons of Rolling Thunder; ” available from Motorbooks International. Girdler's previous books include ' ‘Illustrated H a r lev-Da vidson Buyer's Guide" and "Harley Racers. "

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontDeath of the Fork?

May 1991 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeTalking Hats

May 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

May 1991 -

Roundup

RoundupMore Mini-Rockets From Japan

May 1991 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupStrike Quiets Harley Plant

May 1991 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupTrouble In Nortonland?

May 1991 By Jon F. Thompson