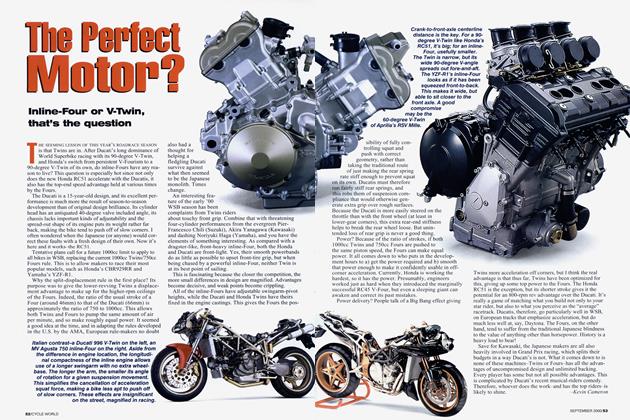

THE BATTLES OF BRITTEN

One man's war to develop the ultimate racebike

ALAN CATHCART

EVERYBODY KNOWS THAT MOST HOME BUILT MOTORcycles are bad news. The majority are crude and ugly, with handling so bizarre and brakes so weird that riding them doubles as an exercise in terror. That hasn't stopped people from brewing their own bikes. lt's an activity that illustrates the individuality coursing so freely though motorcycling all over the world. Rolling your own motorcycle is nothing less than the ultimate two-wheeled expression of self-reliance.

Which brings us to John Britten, a lanky, property developer and one-time vintage racer fron Zealand. He designs motorcycles. And he builds what he’s designed. His latest creation, the Britten V-1000, is so sophisticated and so well finished—and so very fast—that it created an immediate sensation when it first appeared at the 1989 Daytona Pro-Twins event. Unfortunately, it wasn’t a factor in that race.

The teething tr~.whies that are part and parcel of a small time effort to develop a complex. state-of~the-art racehike at first prevented the Britten from obtaining the results o clearly promised. Those troubles lar~ely have involved the bike's home-brewed electronic fuel-injection system. The liquid-cooled V-Twin engine and the very sophisticated carbon-fiber chassis that houses it have proved almost un believably rug~ed and reliable. So when Aussie Paul Lewis brought the bike home second to Doug Polen's Fast By Ferracci Ducati this year in the 50-mile Daytona ProTwins race, those teething troubles seemed solved. Britten finally had a race result to show for his dedication and ingenuity.

`~rhat esuh may translate into something even more substantial. For the Britten now stands a good chance of' being adopted by an established manufacturer. Swiss chas sis-builder Fritz Egli ordered a half-dozen of Britten's en gines~ around which he plans to build a sextet of Twins racers. And Bimota designer Pierluigi Marconi. who favors V-Twins for use in his innovative Tesi chassis. has ex pressed an interest in the VI 000 motor. Early reports that Bimota had ordered 30 engines proved false, but the pos sibility of a Britten-Bimota exists,

iLl %.J 4 ii I lF4L~.IJ~ LFl~1Ri I~ 4~'~ That kind of deal would be just fine with Britten. He says. "I'd really rather hand the whole project over to someone who has the means to put the bike or engine into production. I really only like building prototypes and developing them to the point that they achieve something. After that. I tend to lose interest, and want to be getting on to the next thing."

The key to the Britten’s performance is not just its speed, though it has plenty of that. It went 173 mph at Daytona in 1990. and at the Christchurch Speed Trials in New Zealand, with Britten himself up, it clocked 174. But combined with blazing speed is tractability that is, in a racing engine, purely amazing, as I found out recently when I spent some laps in the bike’s saddle. Britten’s engine will pull cleanly, and very strongly, from as low as 3000 rpm up to 10,000 rpm. After that, power starts to fall off steeply. Compared to a Ducati 888, which must be revved to at least 7000 rpm before it starts to make serious power, the Britten is amazingly torquey. When I sampled it, the engine had survived more than 200 hours of hard use on track and dyno without any mechanical ailment more serious than a broken cam belt.

In addition to being powerful and sturdy, the engine is very smooth—due to careful crankshaft balancing-and this lack of vibration enables Britten to dispense with counterbalancer shafts. That, in turn, contributes to the notable quickness with which the engine picks up revs. With internal friction reduced to a minimum (by using two-ring pistons, for example), the Britten spins very freely and builds engine speed rapidly. Coupled with its ferocious 13.5:1 compression ratio—which requires the bike to be started on rollers using the ignition retard button on the right bar—this gives dramatic acceleration out of corners.

Thanks in part to advice from Mike Sinclair, fellow Kiwi and Wayne Rainey’s race engineer, Britten has created an avant-garde chassis that delivers handling to match the engine’s performance. Definitely tailored for the smaller man, the bike's one-piece seat/tank unit gives a close-coupled riding position, with a high-set seat and low bars that throw much of the rider's weight onto the front wheel, thus helping it stick to the ground under braking and turn entry. Though steering geometry is multi-adjust-

able, Britten prefers fixing the head angle on the White Power upside-down fork at 24.5 degrees, and alters the ride height and trail to suit each circuit.

The bike is surprisingly easy to ride. One good reason for this involves the considerable engine braking available. This seems to place less of a strain on the forearms when nailing the binders during set-up for a corner. The transmission ratios are widely spaced—about 1200 rpm between each gear—and downshifting under braking produces quite remarkable deceleration, making it important to use the back brake gingerly, if at all. A heavy foot on the pedal makes the back wheel hop, with imaginable results. The AP four-piston calipers and Brembo iron discs make for an oddball brake cocktail that works gradually, without a lot of initial bite, a characteristic that makes the engine braking even more welcome.

Upshifting at 8000 rpm delivers impressive acceleration, and wheelies in any of the bottom three ratios, but revving to the 9500-rpm limit that Britten usually imposes reveals a notable extra kick from 8700 rpm upwards. The gearchange is very precise, if a little mechanical. You absolutely cannot rush up to a corner, stand the Britten on its nose with the brakes, and notch down two gears one after another like on any racing two-stroke or, more to the point, a six-speed, eight-valve Ducati. With its five widely spaced ratios, the Britten's gearbox demands more measured use, especially with that sky-high compression ratio waiting to make its presence felt on deceleration.

Surprisingly, in view of its considerable $6/44 forward weight bias, the Britten doesn’t display any traction problems accelerating out of slow turns. You just crank the power on. the bike squats slightly, the rear Michelin digs in, and you’re thundering off to the next turn in a wall of V-Twin sound. Lots of very clever chassis designers and race engineers working with lower power outputs and a lot more cash have tried, and failed, to produce the same sort of traction Britten has achieved. The WP fork works beautifully, giving a large dose of confidence-inspiring neutrality to the steering. The front wheel doesn't wash out half-

way around a turn, nor tuck in on the brakes as you might expect with GP-style geometry. In many ways, the poised, predictable chassis is even more impressive than Britten's state-of-the-art engine.

But that engine really is the key to the equation. It's difficult to convey the sheer thrill of riding such a powerful yet comparatively docile machine. Uncannily free of vibration, tractor-like in its torque delivery, yet capable of revving to the five-figure mark safely, the Britten V-1000 is one of the great motorcycle engines of our day. John Britten has created a mechanical masterpiece. Now it's up to an established manufacturer to assure the engine's longterm development for series production. The Britten is too good, too special, to be just another home-built that goes nowhere. S3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

October 1991 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

October 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

October 1991 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1991 -

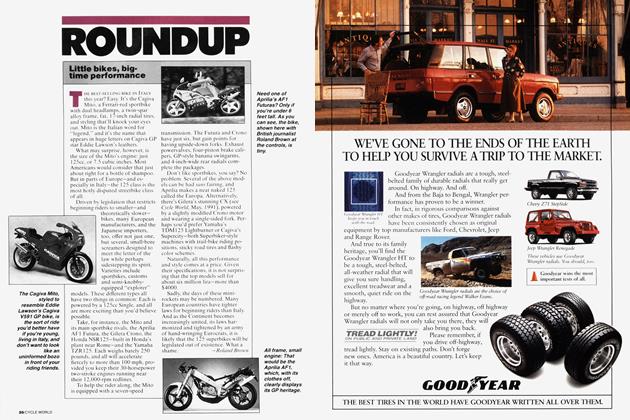

Roundup

RoundupLittle Bikes, Big-Time Performance

October 1991 By Roland Brown -

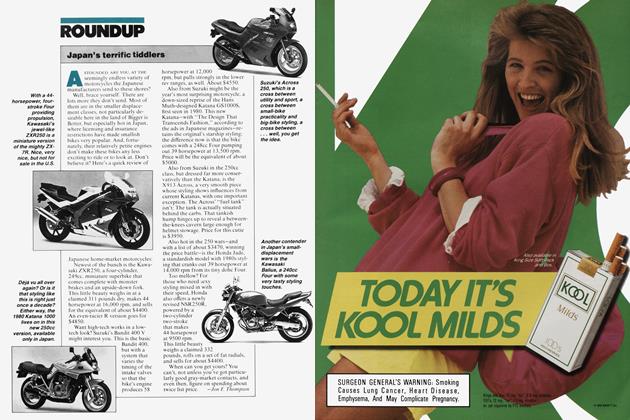

Roundup

RoundupJapan's Terrific Tiddlers

October 1991 By Jon F. Thompson