Talking hats

AT LARGE

Steven L. Thompson

THEY WERE OBVIOUSLY FATHER AND son. He was maybe 40, his son a teenager, and the stamp of shared genes showed in their faces and their mannerisms. They poked around the piles of the rare and the rubbish like any of the rest of us at the old-bike show and swap meet. I kept running into them the way you do at small meets, and it was while we were all thumbing through ancient sales literature at a creaking card table that I saw present and past collide in the father and son.

The kid. as modern kids do, was wearing his baseball cap backwards. His father wore his as guys my age do; the crown slightly dished, the bill rolled just the right amount at the edges. Whitey Ford, all the way.

Neither father's nor son’s cap style surprised me. But when pop thought nobody was looking, he swiftly spun his own cap around until it sat facing backwards on his head just as his son's did. He then reached down and grabbed an old brochure, darting a glance at the boy. 1 wandered away, bemused.

What occupied my thinking wasn't just the obvious poignancy of the father trying so clearly to connect with the son. It wasn't even to wonder if that son knew why he thought wearing his cap backwards was cool. (Does anybody know?) What I thought about was the way what we wear talks, and how nothing—not even T-shirts—talks so much about who we think we are as something we wear on our heads. And how nothing is as potent in doing that as a motorcycle helmet.

How we decorate our helmets tells the world who we think we are. We define our marque allegiances with them, make political statements, sometimes even advertise our sexual proclivities. Our helmets are the billboards of our identities as motorcyclists. Even when they're unadorned or used as supplied by the factory.

Like a lot of what goes on in motorcycling, this aspect of helmets is usually left undiscussed. We prefer to let our helmets do the talking, as it were, and not discuss the psychology of the process. I learned how powerful the psychology is in a session with a small group of high-time riders, roadracers all. who had gathered at a

mutual friend’s house. These guvs are early middle-aged, professional types; one is a former teacher, now a wealthy entrepreneur, another a pro photographer, a third an architect, a fourth a biologist.

The talk turned, as it always seems to among serious riders, to discussion about why any sane man would opt to ride without a helmet. Most agreed that vanity was at the root of most unhelmeted riding, probably more important even than machismo. The consensus was that guys who rode without bone domes just wanted to be singular, their faces thus becoming the most important part of the manmachine combination.

There was a fair amount of condescension in their comments. Understandable, perhaps, from a group of men who’d put their lives on the racing line and knew the value of their safety gear. But their venomous condemnation of their unhelmeted colleagues intrigued me, because there seemed to be more behind it than frustration that the helmetless somehow polluted the social environment for the helmeted.

I asked whether, if some genius invented an invisible helmet—a force field, say, penetrable by air but progressively resistant to impact—they'd “wear” one. Stunned silence greeted the question, and not because of its sci-fi absurdity. As they responded, it became clear that they each enjoyed the presentation of their preferred personalities made possible by their helmets. The sense was that the carefully conceived and executed “face”

of each of their helmets was a better reflection of their identities than the faces nature had given them.

If nothing else, this vignette showed how important is the decoration of the helmet. Some people might imagine it to be of secondary importance, but any racer—or any m a n u fa c t u re r—k n o ws o t h e rw i se. The racer's problem is to present a strong, instantly identifiable image that people —including sponsors— will understand and remember, and the helmet maker’s problem is to sell safety as fashion, since safety per se seems only occasionally to be really saleable. Fashion being fickle by definition, the manufacturers' problem is the same, ultimately, as any commodity makers’: packaging.

This leads to some strange products, such as the seemingly endless supply of replica-star helmets complete with stick-on signatures. It's not a new strategy. Two decades ago, I shared roadrace grids with a lot of guys who wore British helmets painted to replicate Phil Read's or Mike Hailwood's designs. But most of the racers had modified the designs with their own symbology.

For a long time, the same has not been true of the street riders of America. Since the explosion of nichebikes, about '83 or so. we’ve seemed to be a nation of off-the-rack riders, apparently comfortable with factory Aráis and Shoeis and System Ones and Stars. As I rode around America and saw, year after year, little evidence of the creativity that once made most helmets interesting reflections of their owners' values, I wondered if something fundamental had changed.

Wrong again. It was just a widespread fascination with the mid-’80s multicolored zoomie-striped fashion, which most of us figured the factory could doodle better than we could. About spring of last year, a whole slew of helmets must have worn out and been tossed away, because the deal changed again. And now almost everywhere you go. you see wonderfully personalized helmets.

People, once again, are obviously talking through their hats. And enjoying the hell of out it. Father and son alike. E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontDeath of the Fork?

May 1991 By David Edwards -

Letters

LettersLetters

May 1991 -

Roundup

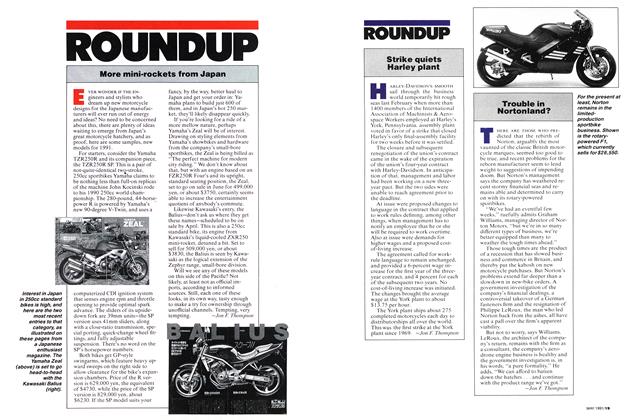

RoundupMore Mini-Rockets From Japan

May 1991 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

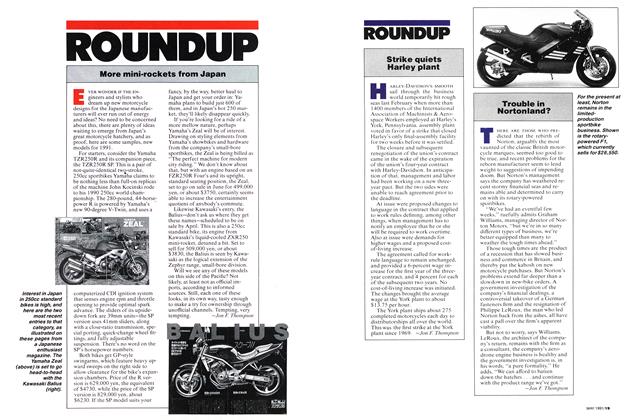

RoundupStrike Quiets Harley Plant

May 1991 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupTrouble In Nortonland?

May 1991 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

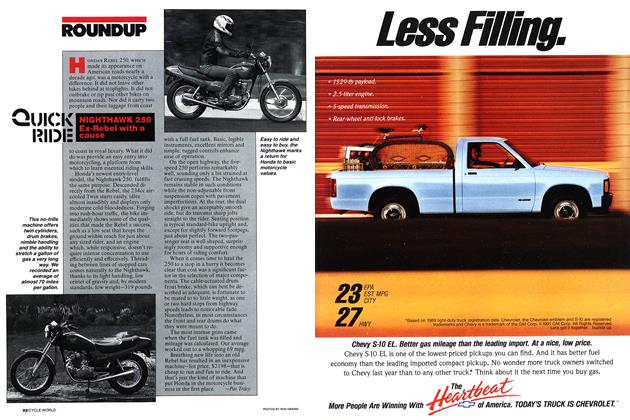

RoundupNighthawk 250 Ex-Rebel With A Cause

May 1991 By Pal Tracy