THE RESURRECTION OF THE RENNSPORT

What better masterwork for a Boxermaster

STEVEN L. THOMPSON

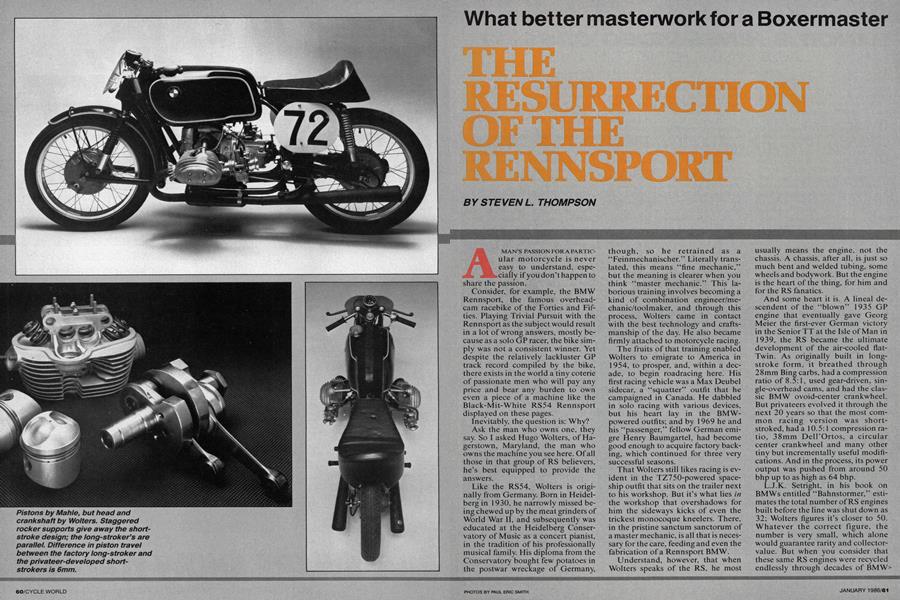

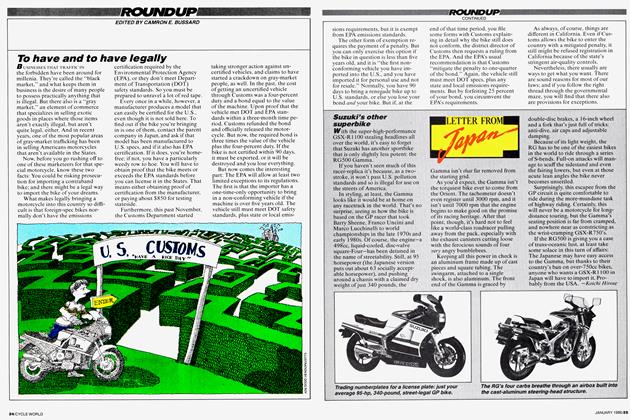

A MAN’S PASSION FOR A PARTICular motorcycle is never easy to understand, especially if you don’t happen to share the passion. Consider, for example, the BMW Rennsport, the famous overhead-cam racebike of the Forties and Fifties. Playing Trivial Pursuit with the Rennsport as the subject would result in a lot of wrong answers, mostly because as a solo GP racer, the bike simply was not a consistent winner. Yet despite the relatively lackluster GP track record compiled by the bike, there exists in the world a tiny coterie of passionate men who will pay any price and bear any burden to own even a piece of a machine like the Black-Mit-White RS54 Rennsport displayed on these pages.

Inevitably, the question is: Why? Ask the man who owns one, they say. So I asked Hugo Wolters, of Hagerstown, Maryland, the man who owns the machine you see here. Of ail those in that group of RS believers, he’s best equipped to provide the answers.

Like the RS54, Wolters is originally from Germany. Born in Heidelberg in 1930, he narrowly missed being chewed up by the meat grinders of World War II, and subsequently was educated at the Heidelberg Conservatory of Music as a concert pianist, in the tradition of his professionally musical family. His diploma from the Conservatory bought few potatoes in the postwar wreckage of Germany, though, so he retrained as a “Feinmechanischer.” Literally translated, this means “fine mechanic,” but the meaning is clearer when you think “master mechanic.” This laborious training involves becoming a kind of combination engineer/mechanic/toolmaker, and through this process, Wolters came in contact with the best technology and craftsmanship of the day. He also became firmly attached to motorcycle racing.

The fruits of that training enabled Wolters to emigrate to America in 1954, to prosper, and, within a decade, to begin roadracing here. His first racing vehicle was a Max Deubel sidecar, a “squatter” outfit that he campaigned in Canada. He dabbled in solo racing with various devices, but his heart lay in the BMWpowered outfits; and by 1969 he and his “passenger,” fellow German emigre Henry Baumgartel, had become good enough to acquire factory backing, which continued for three very successful seasons.

That Wolters still likes racing is evident in the TZ750-powered spaceship outfit that sits on the trailer next to his workshop. But it’s what lies in the workshop that overshadows for him the sideways kicks of even the trickest monocoque kneelers. There, in the pristine sanctum sanctorum of a master mechanic, is all that is necessary for the care, feeding and even the fabrication of a Rennsport BMW.

Understand, however, that when Wolters speaks of the RS, he most usually means the engine, not the chassis. A chassis, after all, is just so much bent and welded tubing, some wheels and bodywork. But the engine is the heart of the thing, for him and for the RS fanatics.

And some heart it is. A lineal descendent of the “blown” 1935 GP engine that eventually gave Georg Meier the first-ever German victory in the Senior TT at the Isle of Man in 1939, the RS became the ultimate development of the air-cooled flatTwin. As originally built in longstroke form, it breathed through 28mm Bing carbs, had a compression ratio of 8.5:1, used gear-driven, single-overhead cams, and had the classic BMW ovoid-center crankwheel. But privateers evolved it through the next 20 years so that the most common racing version was shortstroked, had a 10.5:1 compression ratio, 38mm Dell’Ortos, a circular center crankwheel and many other tiny but incrementally useful modifications. And in the process, its power output was pushed from around 50 bhp up to as high as 64 bhp.

L.J.K. Setright, in his book on BMWs entitled “Bahnstormer,” estimates the total number of RS engines built before the line was shut down as 32; Wolters figures it’s closer to 50. Whatever the correct figure, the number is very small, which alone would guarantee rarity and collectorvalue. But when you consider that these same RS engines were recycled endlessly through decades of BMW> dominance of sidecar GP events in Europe, and that BMW made no new parts after it ceased racing, you begin to glimpse some of the reasons for the Rennsport legend.

That legend is based upon success, but not in solos, to be sure. Despite the numerous stars who plied their skills on the solo GP mount, the bike never became a world-beater (except, ironically, in the capable hands of Kurt Liebmann, who has several times used his RS chassis and Wolters’ engine to win the Vintage race at Daytona). Its hallmarks were a superb power-to-weight ratio courtesy of astonishingly light weight (around 260 pounds), reliability and usable power for those long, tortuous hillclimbs that were interspersed with GP races throughout the season.

Peculiar handling dogged the bike until the factory quit trying to best the lithe, agile British works bikes and the powerful Italian “fire engines.’’ But once the RS was bolted into a sidecar chassis, its virtues became unbeatable and its vices disappeared. Its opposed-Twin width didn’t matter in such an application, its shaft drive became a boon rather than a curse, and it powered so many world champions to victory that for two decades the technical interest in sidecar racing shifted from engine to chassis development—precisely the reverse of what was going on in solo racing at the time.

Someone not in the grip of RS-passion might well ask: So what? What does that make the Rennsport besides just another racing engine well past its prime? Aside from marque freaks, who should care—and why?

When I put this question to Hugo Wolters, he did not answer at first. He pursed his lips and looked past my shoulder for a moment. I knew there was more going on in his head than just a matter of translating subtle German; there was the whole issue of why he had become the keeper of the RS flame, why he had devoted so much of his life’s time to it.

Summarizing his complex answer in a word, the reason is “traditions.’’ The Rennsport embodied a special blend of old-world craftsmanship and new-wave technology; further, it was the pinnacle of achievement for a particular design, the ne plus ultra of the air-cooled flat-Twin. It was also uniquely German, even Bavarian.

BMW used the finest available materials in the RS, but it was the vital interaction between crafstmanship and technology that fascinated Wolters. For example, just the act of timing the engine is a test of knowledge and patience beyond anything your average modern mechanic can imagine. The reason? There are no timing marks on any of the gears in the valve train. Only half-jesting, Wolters smiles and says that this means you have to correctly position 23 gears for each valve. And since many of the gears are common, the problem quickly magnifies itself.

The satisfaction a Feinmechanischer like Hugo Wolters could derive from setting up such an engine is obvious. But it’s easy to wonder why the RS’s designers built it that way, why they didn't simply mark the right settings, as every other factory has always done. Wolters’ answer is that they didn’t because they had something better: They had the years of knowledge and skill in the heads and hands of their master mechanics and engineers. Today, he agrees, such things would be impossible; labor is too expensive, and nobody is willing to put in the years as an apprentice to learn such arcana. But back then, things were different. There were powerful traditions at work, shaping products and the people who built them—including Hugo Wolters.

The RS on these pages is one of six in the world. But it is a replica Rennsport, built mostly by Wolters, not by BMW. Wolters sold his complete “authentic” Georg Meier bike to Helmut Luenemann in Berlin, and losing that machine made it imperative that he carry out his grand plan for the continuation of the RS.

By the early 1970s, says Wolters, the factory had destroyed all of the old tooling for making the RS engine. He managed to salvage key drawings, and although he says the original blueprints for the whole bike are in the archives at BMW, they are virtually unobtainable for use. And use is what he’s been after; because he wants not just to restore Rennsports, but to build new ones. And even improve on them.

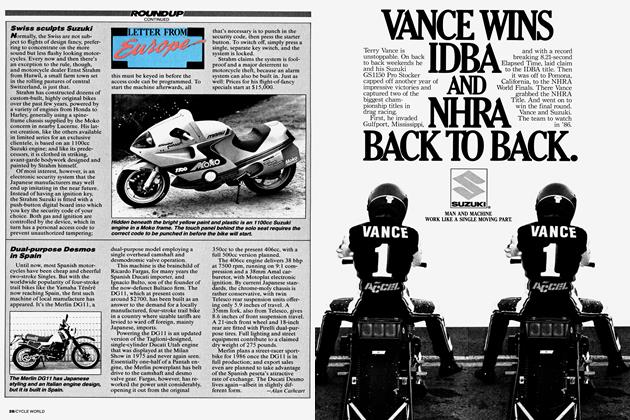

Look at the Wolters/RS cylinder head, for instance, and you are looking at something not from Munich, but from Hagerstown, Maryland. With few exceptions—such as the central frame cradle and the Heimann center-nipple spoked alloy rims, which are BMW original equipment—the entire Rennsport pictured here is also from Wolters’ workshop.

What Hugo Wolters is after is nothing less than immortality for the Rennsport. He figures he can make an entire motorcycle in 10 months— about twice as long as it took the factory. He has invested in having molds made and in finding suppliers for all the bits and raw materials, and as far as he knows, nobody else in the world has done so. “The Germans are too cheap,” he says of the many in Germany who share his passion for the Rennsport but who will not similarly invest time, patience and large chunks of money, “and having molds made there would cost too much.”

So, denied access to overblown, overpriced European craftsmen, Wolters turned to the rolling farmlands around the Maryland-Pennsylvania border. There he located American craftsmen who, as inheritors of the traditions of the Feinmechanischer and also of Yankee ingenuity, take on his projects as an expression of professional pride and ability, if not because of the money to be made.

In this way, the Rennsport story has come full circle. Craftsmanship and professional pride in their abilities were the hallmarks of the men who built the originals, 30 years ago, and so it is fitting that the same pride of craftsmanship drives the construction of the Rennsport replica. It is the best kind of pride: invisible to the ignorant but implicit in every perfectly machined part, every lovingly assembled geartrain. A man who knows says of the Wolters bike that when it was all assembled for the first time, he helped Hugo bump it to life in a narrow little driveway. It fired on the first turn of the rear wheel and immediately barked out its unique Boxer blare. Wolters, he says, was pleased, but not surprised.

Surprise, after all, is for apprentices. The Boxermaster at work on his masterpiece expects nothing less than perfection.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue