Bad Day in Daly City

AT LARGE

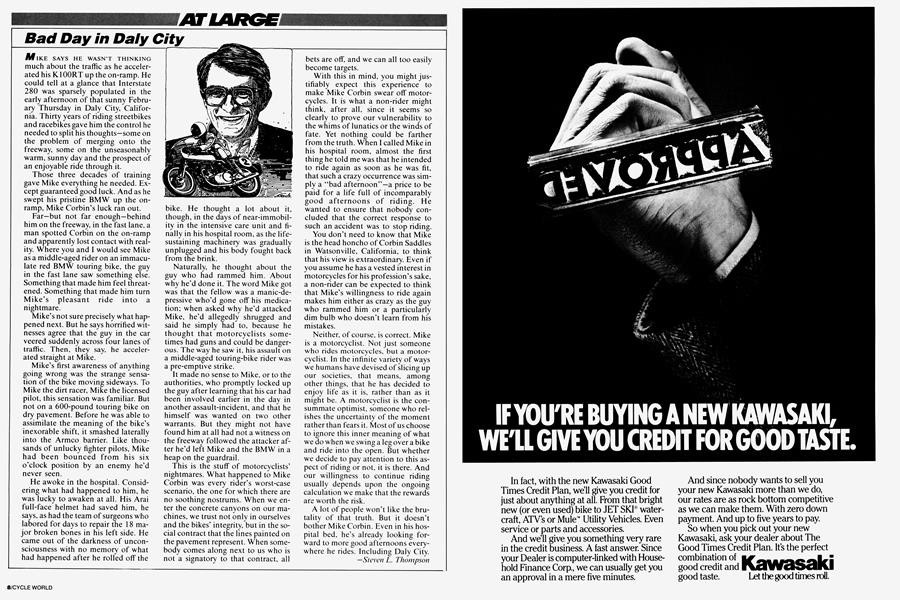

MIKE SAYS HE WASN'T THINKING much about the traffic as he accelerated his K100RT up the on-ramp. He could tell at a glance that Interstate 280 was sparsely populated in the early afternoon of that sunny February Thursday in Daly City, California. Thirty years of riding streetbikes and racebikes gave him the control he needed to split his thoughts—some on the problem of merging onto the freeway, some on the unseasonably warm, sunny day and the prospect of an enjoyable ride through it.

Those three decades of training gave Mike everything he needed. Except guaranteed good luck. And as he swept his pristine BMW up the onramp, Mike Corbin’s luck ran out.

Far—but not far enough—behind him on the freeway, in the fast lane, a man spotted Corbin on the on-ramp and apparently lost contact with reality. Where you and I would see Mike as a middle-aged rider on an immaculate red BMW touring bike, the guy in the fast lane saw something else. Something that made him feel threatened. Something that made him turn Mike’s pleasant ride into a nightmare.

Mike’s not sure precisely what happened next. But he says horrified witnesses agree that the guy in the car veered suddenly across four lanes of traffic. Then, they say, he accelerated straight at Mike.

Mike’s first awareness of anything going wrong was the strange sensation of the bike moving sideways. To Mike the dirt racer, Mike the licensed pilot, this sensation was familiar. But not on a 600-pound touring bike on dry pavement. Before he was able to assimilate the meaning of the bike’s inexorable shift, it smashed laterally into the Armco barrier. Like thousands of unlucky fighter pilots, Mike had been bounced from his six o’clock position by an enemy he’d never seen.

He awoke in the hospital. Considering what had happened to him, he was lucky to awaken at all. His Arai full-face helmet had saved him, he says, as had the team of surgeons who labored for days to repair the 18 major broken bones in his left side. He came out of the darkness of unconsciousness with no memory of what had happened after he rolled off the

bike. He thought a lot about it, though, in the days of near-immobility in the intensive care unit and finally in his hospital room, as the lifesustaining machinery was gradually unplugged and his body fought back from the brink.

Naturally, he thought about the guy who had rammed him. About why he’d done it. The word Mike got was that the fellow was a manic-depressive who’d gone off his medication; when asked why he’d attacked Mike, he’d allegedly shrugged and said he simply had to, because he thought that motorcyclists sometimes had guns and could be dangerous. The way he saw it, his assault on a middle-aged touring-bike rider was a pre-emptive strike.

It made no sense to Mike, or to the authorities, who promptly locked up the guy after learning that his car had been involved earlier in the day in another assault-incident, and that he himself was wanted on two other warrants. But they might not have found him at all had not a witness on the freeway followed the attacker after he’d left Mike and the BMW in a heap on the guardrail.

This is the stuff of motorcyclists’ nightmares. What happened to Mike Corbin was every rider’s worst-case scenario, the one for which there are no soothing nostrums. When we enter the concrete canyons on our machines, we trust not only in ourselves and the bikes’ integrity, but in the social contract that the lines painted on the pavement represent. When somebody comes along next to us who is not a signatory to that contract, all

bets are off, and we can all too easily become targets.

With this in mind, you might justifiably expect this experience to make Mike Corbin swear off motorcycles. It is what a non-rider might think, after all, since it seems so clearly to prove our vulnerability to the whims of lunatics or the winds of fate. Yet nothing could be farther from the truth. When I called Mike in his hospital room, almost the first thing he told me was that he intended to ride again as soon as he was fit, that such a crazy occurrence was simply a “bad afternoon’’—a price to be paid for a life full of incomparably good afternoons of riding. He wanted to ensure that nobody concluded that the correct response to such an accident was to stop riding.

You don’t need to know that Mike is the head honcho of Corbin Saddles in Watsonville, California, to think that his view is extraordinary. Even if you assume he has a vested interest in motorcycles for his profession’s sake, a non-rider can be expected to think that Mike’s willingness to ride again makes him either as crazy as the guy who rammed him or a particularly dim bulb who doesn’t learn from his mistakes.

Neither, of course, is correct. Mike is a motorcyclist. Not just someone who rides motorcycles, but a motorcyclist. In the infinite variety of ways we humans have devised of slicing up our societies, that means, among other things, that he has decided to enjoy life as it is, rather than as it might be. A motorcyclist is the consummate optimist, someone who relishes the uncertainty of the moment rather than fears it. Most of us choose to ignore this inner meaning of what we do when we swing a leg over a bike and ride into the open. But whether we decide to pay attention to this aspect of riding or not, it is there. And our willingness to continue riding usually depends upon the ongoing calculation we make that the rewards are worth the risk.

A lot of people won't like the brutality of that truth. But it doesn’t bother Mike Corbin. Even in his hospital bed, he’s already looking forward to more good afternoons everywhere he rides. Including Daly City.

Steven L. Thompson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialAmerican Racewatching's Finest Hour

July 1988 By Paul Dean -

Leanings

LeaningsRadio Daze

July 1988 By Peter Egan -

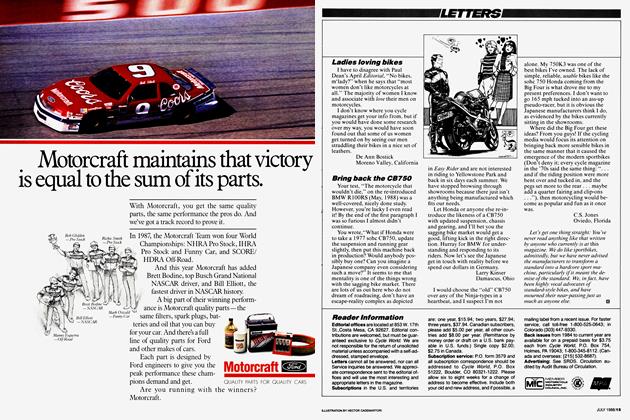

Letters

LettersLetters

July 1988 -

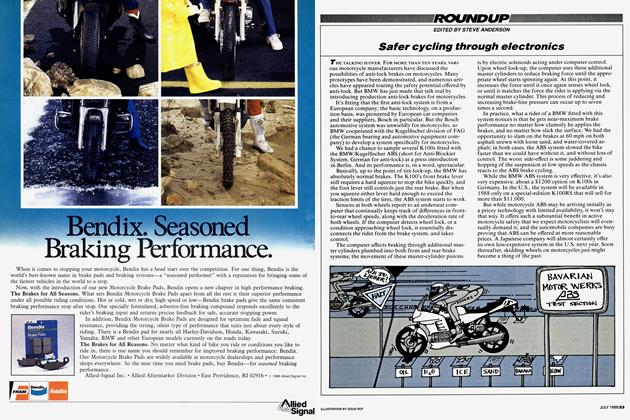

Roundup

RoundupSafer Cycling Through Electronics

July 1988 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

July 1988 By Alan Cathcart -

Destinations

July 1988 By Steve Anderson