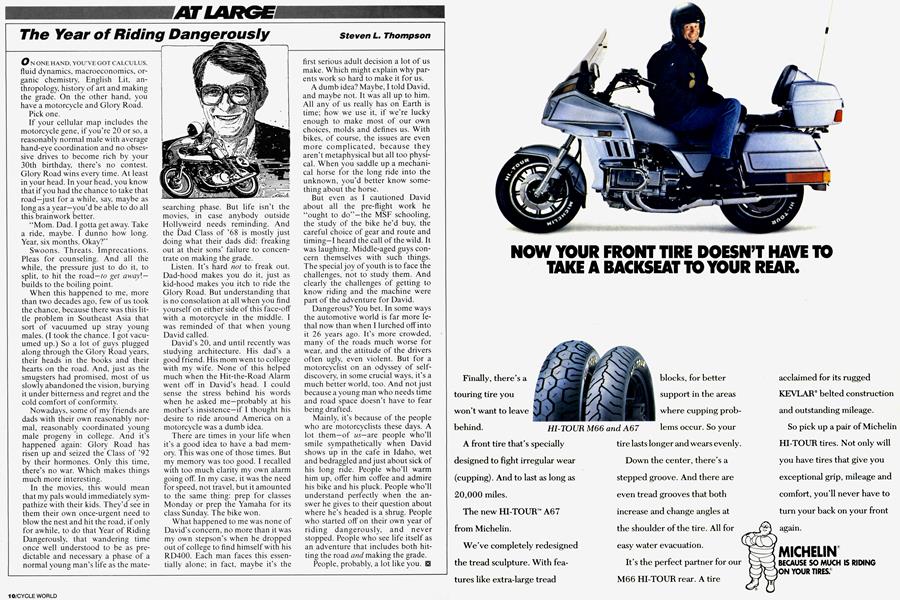

The Year of Riding Dangerously

AT LARGE

Steven L. Thompson

ON ONE HAND, YOU’VE GOT CALCULUS, fluid dynamics, macroeconomics, organic chemistry, English Lit, anthropology, history of art and making the grade. On the other hand, you have a motorcycle and Glory Road.

Pick one.

If your cellular map includes the motorcycle gene, if you’re 20 or so, a reasonably normal male with average hand-eye coordination and no obsessive drives to become rich by your 30th birthday, there’s no contest. Glory Road wins every time. At least in your head. In your head, you know that if you had the chance to take that road—just for a while, say, maybe as long as a year—you’d be able to do all this brainwork better.

“Mom. Dad. I gotta get away. Take a ride, maybe. I dunno how long. Year, six months. Okay?”

Swoons. Threats. Imprecations. Pleas for counseling. And all the while, the pressure just to do it, to split, to hit the road—to get away\— builds to the boiling point.

When this happened to me, more than two decades ago, few of us took the chance, because there was this little problem in Southeast Asia that sort of vacuumed up stray young males. (I took the chance. I got vacuumed up.) So a lot of guys plugged along through the Glory Road years, their heads in the books and their hearts on the road. And, just as the smugsters had promised, most of us slowly abandoned the vision, burying it under bitterness and regret and the cold comfort of conformity.

Nowadays, some of my friends are dads with their own reasonably normal, reasonably coordinated young male progeny in college. And it’s happened again: Glory Road has risen up and seized the Class of ’92 by their hormones. Only this time, there’s no war. Which makes things much more interesting.

In the movies, this would mean that my pals would immediately sympathize with their kids. They'd see in them their own once-urgent need to blow the nest and hit the road, if only for awhile, to do that Year of Riding Dangerously, that wandering time once well understood to be as predictable and necessary a phase of a normal young man’s life as the matesearching phase. But life isn’t the movies, in case anybody outside Hollyweird needs reminding. And the Dad Class of ’68 is mostly just doing what their dads did: freaking out at their sons’ failure to concentrate on making the grade.

Listen. It’s hard not to freak out. Dad-hood makes you do it, just as kid-hood makes you itch to ride the Glory Road. But understanding that is no consolation at all when you find yourself on either side of this face-off with a motorcycle in the middle. I was reminded of that when young David called.

David’s 20, and until recently was studying architecture. His dad’s a good friend. His mom went to college with my wife. None of this helped much when the Hit-the-Road Alarm went off in David's head. I could sense the stress behind his words when he asked me—probably at his mother’s insistence—if I thought his desire to ride around America on a motorcycle was a dumb idea.

There are times in your life when it’s a good idea to have a bad memory. This was one of those times. But my memory was too good. I recalled with too much clarity my own alarm going off In my case, it was the need for speed, not travel, but it amounted to the same thing: prep for classes Monday or prep the Yamaha for its class Sunday. The bike won.

What happened to me was none of David’s concern, no more than it was my own stepson’s when he dropped out of college to find himself with his RD400. Each man faces this essentially alone; in fact, maybe it’s the first serious adult decision a lot of us make. Which might explain why parents work so hard to make it for us.

A dumb idea? Maybe, I told David, and maybe not. It was all up to him. All any of us really has on Earth is time; how we use it, if we’re lucky enough to make most of our own choices, molds and defines us. With bikes, of course, the issues are even more complicated, because they aren’t metaphysical but all too physical. When you saddle up a mechanical horse for the long ride into the unknown, you’d better know something about the horse.

But even as I cautioned David about all the pre-flight work he “ought to do”—the MSF schooling, the study of the bike he’d buy, the careful choice of gear and route and timing—I heard the call of the wild. It was laughing. Middle-aged guys concern themselves with such things. The special joy of youth is to face the challenges, not to study them. And clearly the challenges of getting to know riding and the machine were part of the adventure for David.

Dangerous? You bet. In some ways the automotive world is far more lethal now than when I lurched off into it 26 years ago. It’s more crowded, many of the roads much worse for wear, and the attitude of the drivers often ugly, even violent. But for a motorcyclist on an odyssey of selfdiscovery, in some crucial ways, it’s a much better world, too. And not just because a young man who needs time and road space doesn’t have to fear being drafted.

Mainly, it’s because of the people who are motorcyclists these days. A lot them—of us—are people who’ll smile sympathetically when David shows up in the cafe in Idaho, wet and bedraggled and just about sick of his long ride. People who’ll warm him up, offer him coffee and admire his bike and his pluck. People who’ll understand perfectly when the answer he gives to their question about where he’s headed is a shrug. People who started off on their own year of riding dangerously, and never stopped. People who see life itself as an adventure that includes both hitting the road and making the grade.

People, probably, a lot like you. 13

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontWelcome Back, Honda

December 1989 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Museum of Prehistoric Helmets

December 1989 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1989 -

Roundup

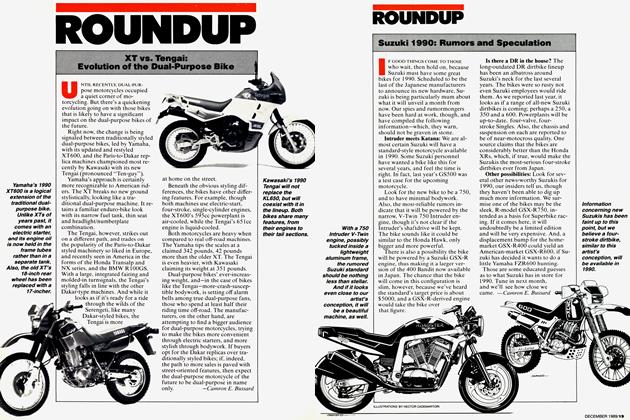

RoundupXt Vs. Tengai: Evolution of the Dual-Purpose Bike

December 1989 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

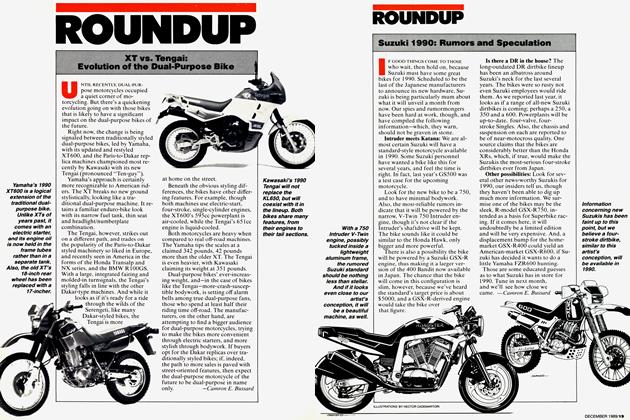

RoundupSuzuki 1990: Rumors And Speculation

December 1989 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

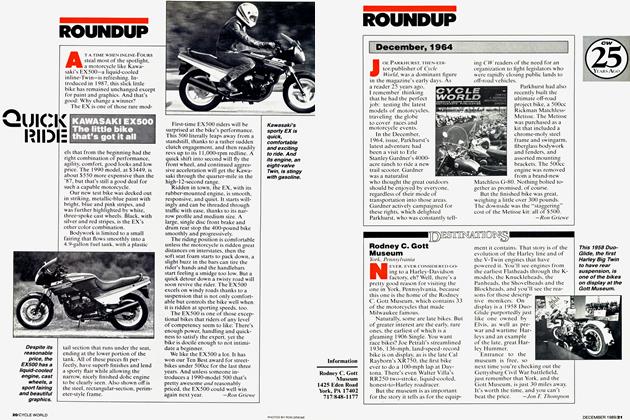

RoundupQuick Ride

December 1989 By Ron Griewe