AT LARGE

The Fat Cat of Pitcairn Island

Steven L. Thompson

THE SCENE WAS ONE ANY RIDER would recognize: Around a motorcycle shipping crate, a group of people waited in obvious anticipation while the cardboard shell was removed. When it at last came free and the bike inside was revealed, the cries of delight and appreciation were as familiar as the obvious urge the people felt to get on the thing and ride.

Two things were different about this unveiling of another new motorcycle. First, the cardboard box proclaimed the bike inside to be a California-specification Honda VFR700, which it was not. And second, the unveiling was taking place on Pitcairn Island, in the Pacific Ocean.

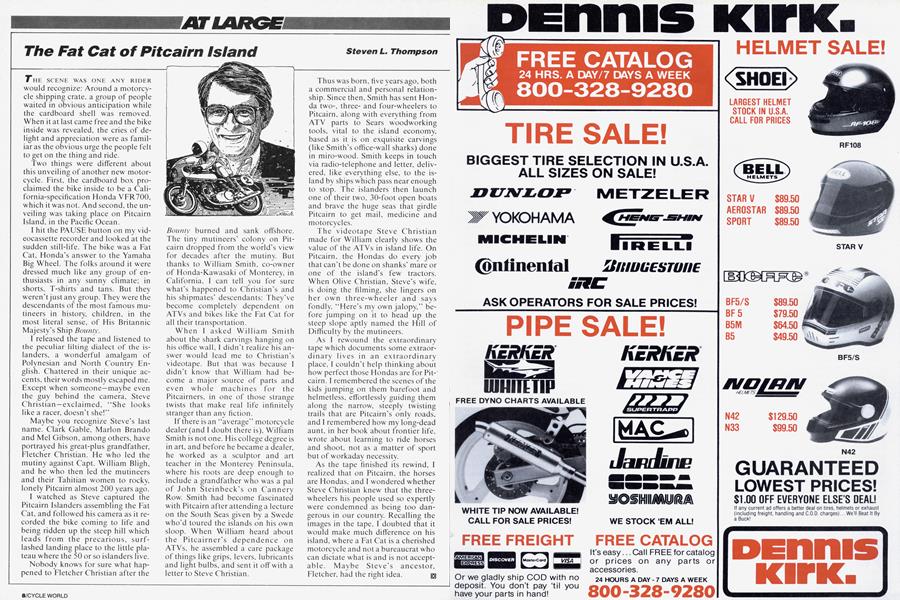

I hit the PAUSE button on my videocassette recorder and looked at the sudden still-life. The bike was a Fat Cat, Honda’s answer to the Yamaha Big Wheel. The folks around it were dressed much like any group of enthusiasts in any sunny climate; in shorts, T-shirts and tans. But they weren’t just any group. They were the descendants of the most famous mutineers in history, children, in the most literal sense, of His Britannic Majesty’s Ship Bounty.

I released the tape and listened to the peculiar lilting dialect of the islanders, a wonderful amalgam of Polynesian and North Country English. Chattered in their unique accents, their words mostly escaped me. Except when someone—maybe even the guy behind the camera, Steve Christian—exclaimed, “She looks like a racer, doesn’t she!”

Maybe you recognize Steve’s last name. Clark Gable, Marlon Brando and Mel Gibson, among others, have portrayed his great-plus grandfather, Fletcher Christian. He who led the mutiny against Capt. William Bligh, and he who then led the mutineers and their Tahitian women to rocky, lonely Pitcairn almost 200 years ago.

I watched as Steve captured the Pitcairn Islanders assembling the Fat Cat, and followed his camera as it recorded the bike coming to life and being ridden up the steep hill which leads from the precarious, surflashed landing place to the little plateau where the 50 or so islanders live.

Nobody knows for sure what happened to Fletcher Christian after the Bounty burned and sank offshore. The tiny mutineers’ colony on Pitcairn dropped from the world’s view for decades after the mutiny. But thanks to William Smith, co-owner of Honda-Kawasaki of Monterey, in California, I can tell you for sure what’s happened to Christian’s and his shipmates’ descendants: They've become completely dependent on ATVs and bikes like the Fat Cat for all their transportation.

When I asked William Smith about the shark carvings hanging on his office wall, I didn’t realize his answer would lead me to Christian’s videotape. But that was because I didn’t know that William had become a major source of parts and even whole machines for the Pitcairners, in one of those strange twists that make real life infinitely stranger than any fiction.

If there is an “average” motorcycle dealer (and I doubt there is), William Smith is not one. His college degree is in art, and before he became a dealer, he worked as a sculptor and art teacher in the Monterey Peninsula, where his roots are deep enough to include a grandfather who was a pal of John Steinbeck’s on Cannery Row. Smith had become fascinated with Pitcairn after attending a lecture on the South Seas given by a Swede who'd toured the islands on his own sloop. When William heard about the Pitcairner’s dependence on ATVs, he assembled a care package of things like grips, levers, lubricants and light bulbs, and sent it off with a letter to Steve Christian.

Thus was born, five years ago, both a commercial and personal relationship. Since then. Smith has sent Honda two-, threeand four-wheelers to Pitcairn, along with everything from ATV parts to Sears woodworking tools, vital to the island economy, based as it is on exquisite carvings (like Smith’s office-wall sharks) done in miro-wood. Smith keeps in touch via radio-telephone and letter, delivered, like everything else, to the island by ships which pass near enough to stop. The islanders then launch one of their two. 30-foot open boats and brave the huge seas that girdle Pitcairn to get mail, medicine and motorcycles.

The videotape Steve Christian made for William clearly shows the value of the ATVs in island life. On Pitcairn, the Hondas do every job that can’t be done on shanks’ mare or one of the island’s few tractors. When Olive Christian, Steve’s wife, is doing the filming, she lingers on her own three-wheeler and says fondly, “Here’s my own jalopy,” before jumping on it to head up the steep slope aptly named the Hill of Difficulty by the mutineers.

As I rewound the extraordinary tape which documents some extraordinary lives in an extraordinary place, I couldn’t help thinking about how perfect those Hondas are for Pitcairn. I remembered the scenes of the kids jumping on them barefoot and j helmetless, effortlessly guiding them along the narrow, steeply twisting trails that are Pitcairn’s only roads, and I remembered how my long-dead aunt, in her book about frontier life, wrote about learning to ride horses and shoot, not as a matter of sport but of workaday necessity.

As the tape finished its rewind, I realized that on Pitcairn, the horses are Hondas, and I wondered whether Steve Christian knew that the threewheelers his people used so expertly were condemned as being too dangerous in our country. Recalling the images in the tape, I doubted that it would make much difference on his island, where a Fat Cat is a cherished motorcycle and not a bureaucrat who can dictate what is and is not acceptable. Maybe Steve's ancestor, Fletcher, had the right idea. g]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

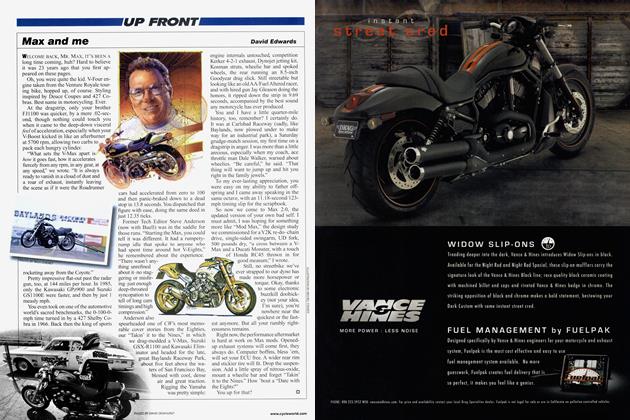

ColumnsUp Front

August 1989 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

August 1989 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1989 -

Roundup

RoundupNew, Top-Secret Triumph Revealed

August 1989 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupFor Japan Only: the High-Tech 250s

August 1989 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupQuick Ride

August 1989 By Alan Cathcart