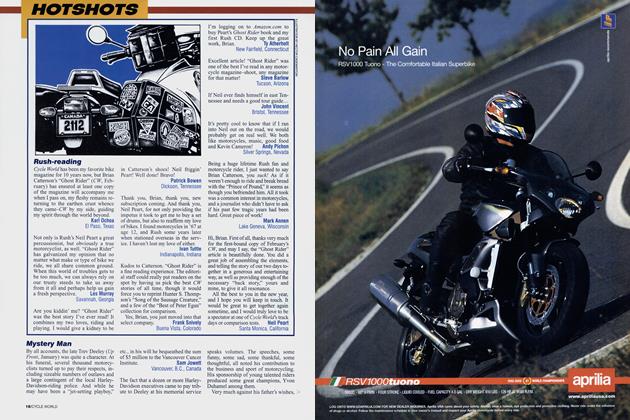

Art of the Ride

UP FRONT

David Edwards

FIFTEEN MONTHS IS A LONG TIME BEtween kickstarts, but as soon as I swung a leg over my 1940 Indian bob-job the procedure came back like it was yesterday: Gas taps on, full choke, full throttle, magneto retarded, ignition off, three priming kicks, choke clicked back to notch one, ignition on, raise up on the lever, think good thoughts and follow through on the downstroke.

I’m happy to report that the Sport Scout, on display in Las Vegas at the Guggenheim Museum’s “Art of the Motorcycle” exhibit since October, 2001, re-lit on the first kick.

With the Linkert’s choke plate fully open, the Fairbanks-Morse mag persuaded into its advanced position by the heel of my right boot, the oil tank uncapped and peered into to confirm lubricant was burbling back through the return tube, the suicide clutch cycled a few times to ensure its plates were unstuck, and the 8-ball shift knob yanked firmly back into first, it was time for a ride.

Not that the stroker Scout isn’t pretty well-traveled already. An ex-Army bike, it was de-mobbed after WWII, turned into a rough-and-tumble county fair flattracker, raced until aged and infirm, then unceremoniously retired to the swapmeet circuit, knocking around for years mostly unloved and unwanted. In search of the start point for a project bobber, I met up with it in 1994 at Indian Engineering, a Stanton, California, restoration shop manned by Jerry Greer and John Bivens. Two years (and numerous Visa receipts) later, they rolled out their handiwork, resplendent in silver-andblack scallops, red pinstripes and bomber-style Varga Girl nose art on the tank. Much to Biv’s consternation, all that was soon slathered in an insidious coating of alkali dust as Jerry aimed the bike across Muroc Dry Lake at 100-plus mph during a big hot-rod reunion. It hosed off and polished up pretty well, though, good enough to win its class at the prestigious Del Mar Concours.

Then the Guggenheim came calling. What began as a four-month exhibition housed in architect Frank Lloyd Wright’s Manhattan landmark ended up running for almost four years, with stops in Chicago’s Field Museum, northern Spain’s fanciful Guggenheim Bilbao facility and finally Las Vegas, installed spectacularly in the Guggenheim’s Venetian Hotel showcase. Worldwide, something like 2 million attendees turned out to see “The Art of the Motorcycle,” making it one of the most successful art exhibitions ever.

The show was conceived in the late 1980s by the Guggenheim’s forwardthinking director, Thomas Krens. A longtime rider, Krens spent one summer during his graduate studies touring Europe on a BMW R90S purchased at the factory, going as far afield as Afghanistan. He still has the bike, but these days runs a more modem RI 150GS.

“The logic behind the show?” asks Krens. “There was no reason for motorcycles not to be considered. They’re objects of complexity, of history, of design, of technology, of aesthetics, of cultural statement. For museums to show interest in 2000-year-old Greek vases, meant to transport water and wine and olive oil around the Mediterranean, to treat these with scholarly reverence, but not look at motorcycles is a colossal conceit.”

That kind of talk goaded many in the highbrow art community, further hacked off when it was announced that BMW would underwrite some the show’s considerable expenses.

“It was a motorcycle show,” says Krens. “You’re not going to approach a toothpaste company for funding. In the end, it was a non-issue. People loved the show, the institution didn’t explode, paintings are still shown. But from time to time museums need to do these things, not be so narrow-focused.”

Amen to that says Ultan Guilfoyle, expatriate Irishman, documentary filmmaker, Norton Commando owner, Ducati Monster commuter and one of the show’s co-curators.

“Motorcycles are now recognized as legitimate design objects, not something that fell off the back of a lorry,” he says. “Whether it’s ink to paper or welding torch to metal, there’s a newfound appreciation for motorcycles among the sometimes-elitist design community. The great cars and their designers were recognized-GM’s Harley Earl, Alec Issigonis of Morris Mini fame, J Mays with his neo-Beetle and neo-Thunderbird-but motorcycle designers like Massimo Tamburini and Willie G. Davidson were barely known outside their own circle. Now motorcycles have a secure place in the thinking of the design world.” Guilfoyle’s curatorial partner was Charles Falco, a professor of optic sciences and owner of 18 motorcycles, everything from a Vincent Black Shadow to a new Honda Interceptor. He sees the show as a mind-expanding eventfor academia and for riders.

“Used to be, ‘If it’s not a Van Gogh, it’s not worthy,”’ he says. “But this show shook the museum world. You can bet directors now know their limits are much wider than before.”

Falco has also become a regular on the lecture circuit, talking about bikes in the halls of higher learning. His “The Art and Science of the Motorcycle” was recently heard at Princeton, given from the same lectern used in the past by such luminaries as Dylan Thomas, Linus Pauling, Carl Sagan, Richard Leakey and J. Robert Oppenheimer.

Closer to home, he sees an increased appreciation for design among riders.

“Motorcyclists are normally very conservative,” he says. “But if style becomes a selling point and buyers are willing to experiment, that opens up the designer’s palette that much more.” Think back to the most talkedabout models of the past couple of years-Willie G’s V-Rod, Terblanche’s Ducati 999, the Ness-influenced Victory Vegas, Kawasaki’s Z1000, Honda’s Valkyrie Rune-and it’s clear that a new era of motorcycle design is upon us.

Anybody for “The Art of the Motorcycle II?”