Safer cycling through electronics

ROUNDUP

STEVE ANDERSON

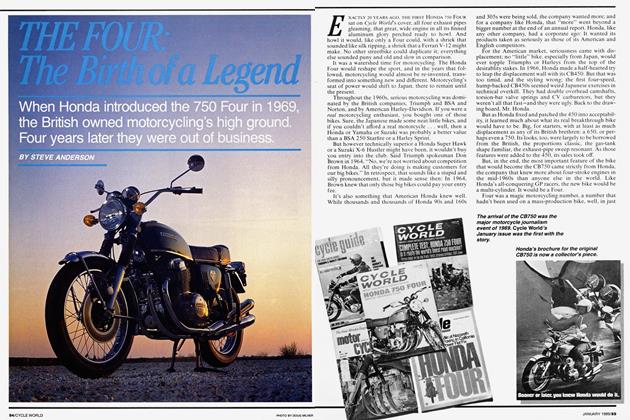

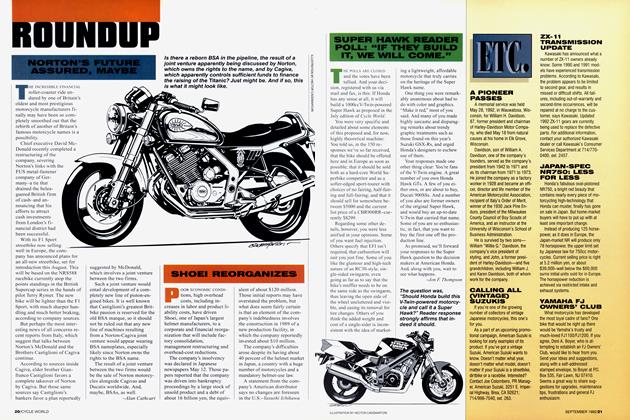

The TALKING IS OVER. FOR MORE THAN TEN YEARS, VARIous motorcycle manufacturers have discussed the possibilities of anti-lock brakes on motorcycles. Many prototypes have been demonstrated, and numerous articles have appeared touting the safety potential offered by anti-lock. But BMW has just made that talk real by introducing production anti-lock brakes for motorcycles.

It’s fitting that the first anti-lock system is from a European company; the basic technology, on a production basis, was pioneered by European car companies and their suppliers, Bosch in particular. But the Bosch automotive system was unwieldly for motorcycles, so BMW cooperated with the Kugelfischer division of FAG (the German bearing and automotive equipment company) to develop a system specifically for motorcycles.

We had a chance to sample several KlOOs fitted with the BMW/Kugelfischer ABS (short for Anti-Blockier System, German for anti-lock) at a press introduction in Berlin. And its performance is, in a word, spectacular.

Basically, up to the point of tire lock-up, the BMW has absolutely normal brakes. The K 100’s front brake lever still requires a hard squeeze to stop the bike quickly, and the foot lever still controls just the rear brake. But when you squeeze either lever hard enough to exceed the traction limits of the tires, the ABS system starts to work.

Sensors at both wheels report to an underseat computer that continually keeps track of differences in frontto-rear wheel speeds, along with the deceleration rate of both wheels. If the computer detects wheel lock, or a condition approaching wheel lock, it essentially disconnects the rider from the brake system, and takes control.

The computer affects braking through additional master cylinders plumbed into both front and rear brake systems; the movement of these master-cylinder pistons

is by electric solenoids acting under computer control. Upon wheel lock-up, the computer uses these additional master cylinders to reduce braking force until the appropriate wheel starts spinning again. At this point, it increases the force until it once again senses wheel lock, or until it matches the force the rider is applying via the normal master cylinder. This process of reducing and increasing brake-line pressure can occur up to seven times a second.

In practice, what a rider of a BMW fitted with this system notices is that he gets near-maximum brake performance no matter how clumsily he applies the brakes, and no matter how slick the surface. We had the opportunity to slam on the brakes at 60 mph on both asphalt strewn with loose sand, and water-covered asphalt; in both cases, the ABS system slowed the bike faster than we could have without it, and without loss of control. The worst side-effect is some juddering and hopping of the suspension at low speeds as the chassis reacts to the ABS brake cycling.

While the BMW ABS system is very effective, it’s also very expensive, about a $ 1200 option on KlOOs in Germany. In the U.S., the system will be available in 1988 only on a special-edition K100RS that will sell for more than $ 11,000.

But while motorcycle ABS may be arriving initially as a pricey technology with limited availability, it won’t stay that way. It offers such a substantial benefit in active motorcycle safety that we expect motorcyclists will eventually demand it; and the automobile companies are busy proving that ABS can be offered at more reasonable prices. A Japanese company will almost certainly offer its own less-expensive system in the U.S. next year. Soon thereafter, skidding wheels on motorcycles just might become a thing of the past.

A visit with Rotax

After our trip to Berlin to see BMW’s anti-lock brake system, we detoured on the way home to rural Austria, and the small town of Gunskirchen. There, Rotax, the engine division of Bombardier, is enjoying the type of success that’s too rare in today’s motorcycling world.

Rotax recently hired its 1000th worker, reaching a level of employment that it has seen only once before. That was in 1972, in the middle of the snowmobile boom, when Rotax supplied Bombardier with 200,000 engines for its Ski-Doo snowmobiles. Employment fell to 600 in the snowmobile market crash that followed, and the motorcycle engines Rotax built for Can-Am couldn’t take up the slack.

Rotax’s current good times come largely from its policy of diversification, and from its alliance with Italian motorcycle manufacturer Aprilia. After suffering the traumas of the snowmobile crash, Rotax didn’t want to be nearly so dependent on a single market. In the past decade, Rotax has expanded its business into engines for ultralight aircraft, boats, fire pumps and agricultural equipment. Currently, snowmobile engines account for only 37 percent of total sales.

But the best part is the strong relationship that Rotax has developed with Aprilia. In Aprilia, Rotax has found a chassis manufacturer whose expertise matches its own with engines. In the past three years, Aprilia has been the only Italian motorcycle company to log consistent growth, and it now holds second place among Italian companies, behind Gilera but ahead of Cagiva. And all Aprilias of 125cc and larger use Rotax engines, explaining why motorcycle powerplants currently make up 25 percent of Rotax’s total production.

The future looks bright for both companies, as Aprilia is busily expanding beyond the Italian market, establishing sales beachheads in France, Germany and Japan. We expect to see Aprilias in the U.S. by 1990 or so. To help

that expansion along, there will likely be some new engines emerging from Rotax. The only product that Rotax General Manager Karl Potzlberger would confirm is a new high-tech four-stroke Single that might make its debut before the end of this year, though no details are available. There was no sign of the long-rumored large displacement four-stroke Twin when we toured Rotax’s R&D facility.

We did see the small assembly area where two men build all of Rotax’s roadracing engines. The Rotax discvalve tandem-Twin 250 powered an Aprilia chassis to a Grand Prix win last season, and currently offers the only alternative to Honda and Yamaha 250 production racers. Head of R&D, Dr. Fippitsch, confirmed that Rotax would continue development with disc-valve engines, a field it largely has to itself now that all Japanese roadracing two-strokes rely on reed valves.

For now, Rotax engines will make themselves felt in the U.S. in fairly small numbers: in ATK dirtbikes, in Wood-Rotax racebikes, in a handful of 250cc roadracers, and in the few Matchless Singles imported to the U.S.

But the Aprilia-Rotax alliance is proving a powerful one that surely will one day make a large impression in the American motorcycle market.

1989 Rumors

A s we pass into the hottest part of summer, the rumors are just beginning to fly about what the chillier fall may bring. As usual, we can’t be sure which of these stories of new motorcycles will come true, but we're equally sure that some are spot-on.

Honda: will offer several new models and updates on old ones. The CBR1000 Hurricane will be Honda’s first model to use the Fucas/Girling-derived all-mechanical anti-lock brakes, which carry a much smaller price penalty than the expensive BMW electronic ABS. Honda will also give the 650 Hawk GT a larger brother, with a

new Hawk V-Twin in the 900-to-1000cc range. V-Four fans may have something to cheer about, as well, for at least one version of the Interceptor will return. The rumors disagree on exactly what that motorcycle will be, however. One claims it will be an updated sporty 750 using many RC30 pieces, such as the RC30’s compact cylinder heads and 360-degree crankshaft. Another says Honda will offer a VFR900 set up to compete directly with Kawasaki’s Concours 1000 and BMW’s K100RS sport-tourers. Only time will tell.

Kawasaki: will go head-to-head with the racier 750 superbikes, and bring back its speed-demon ZX-10 Ninja unchanged. Joining it will be a new ZX-7 Ninja, an aluminum-framed 750cc replica of a motorcycle Kawasaki has entered in selected races this year. Suzuki’s GSX-R750 will be the target, though the Kawasaki may have a few compromises in riding position to make it a better streetbike. If you want to know what the ZX-7 will look like, imagine a smaller, lighter and racier ZX-10, and wait for photos from this July’s Suzuka 8-hour. We predict the machine Kawasaki enters there will be nearly visually identical with the production ZX-7.

Suzuki: will update the GSX-R 1 100, and mount an attack on European enduro-bike turf. Unchanged for three years, the GSX-R 1100 should get an upgraded, GSX-R750-like chassis, and perhaps the 1127cc engine of the large Katana. But with the Danforth bill still a recent memory, Suzuki may not go all-out in increasing power and speed on this biggest GSX-R, and may only nudge top-end performance up slightly while improving torque and handling. Bad news for Husqvarna and KTM will the Suzuki RM/E, a 250cc enduro bike based directly on the RM250 motocrosser. Taking a page from the Europeans’ book, this new Suzuki will be a motocrosser with lights, better muffling and slightly more flywheel, but with chassis and suspension in full motocross trim.

As such, it should be an out-of-the-box threat at enduros.

Yamaha: will update several of its key sportbikes, and return a popular model to the U.S. The FZR750 will have engine and chassis improvements aimed at making it more competitive in U.S. and World Championship Superbike races, and to compete more effectively in the showroom with Suzuki’s big-selling GSX-R750. This new 750 may join Ducati’s 851 in wearing fuel injection instead of carburetors. We also will see an FZR600, a machine better able to compete with Hurricanes and Katanas than the FZ600 with its long-in-the-tooth, twovalve, air-cooled engine. And the FJ 1200 will be back, more comfortable than ever, to retake its place as the gentleman’s superbike. The chassis will benefit from updating with new wheel sizes and radial tires. One rumor does suggest, though, that the FJ might not remain a 1200. But is the world ready for the torque that could be produced by an FJ 1300?

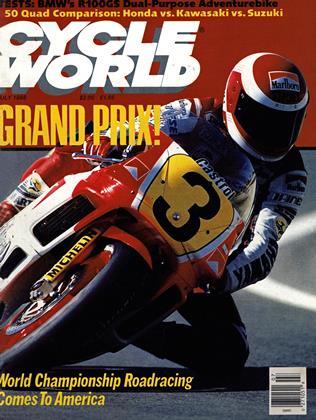

News from Mr. Norton

A recent visitor to our offices was Philippe Le Roux, the Chairman, Managing Director and principal architect of Norton Group PLC. Le Roux bought Norton from its long-time owners, Manganese Bronze, in June of 1987, and has since been busy resurrecting one of the most famous names in motorcycling.

“Ultimately, we want to sell engines,” says Le Roux. Research on Wankel-type rotary engines had been underway at Norton for more than 15 years, and had continued after motorcycle production ceased. The new management is intent on seeing commercial returns on that work. The emphasis of the company, according to Le Roux, is to “produce rotary engines for applications where power and weight are critical.”

Many of those applications fall into the military and aviation realms, and include powering military generator sets, unmanned drones, and ultralight and experimental aircraft. To that effect, Norton has developed a range of

oneand two-rotor Wankels that produce anywhere from eight to 1 50 horsepower. The company just spent $750,000 in new tooling to take in-house more of the machining of components for these engines.

But motorcycles have not been forsaken. While early on. Le Roux was advised to give up on bikes, he says, “I couldn’t can the motorcycles.” He wants to make a successful, balanced company that will eventually produce 1000 or more very special, and fairly expensive, rotary-powered motorcycles a year. The first steps in that direction were the stepping up of spare-parts production for old Commandos—a move that Le Roux said was very profitable—and last year’s production and sale of 100 rotary-powered Norton Classics (Cycle World, March, 1988).

This year will see further progress on the motorcycling front. Just released is the Norton Commander in police trim. It is a K100RT-like touring bike that uses the latest, very lightweight, liquid-cooled version of the Norton twin-rotor Wankel. The police model will be followed by a twin-seat civilian model late this summer. Development will also continue with the racing version of the Norton Wankel, which is producing more than 145 horsepower with a very broad power curve in its latest incarnation. But power is not a problem; instead, handling is, and the next machine built will use the lighterweight liquid-cooled rotary in a new chassis that carries the engine higher. (Just as Honda did with Freddie Spencer’s first NSR500, Norton has discovered it's possible to build a motorcycle with too low a center of gravity.) England’s AMA equivalent, the ACU, will allow the rotary to race in the English 750 class and at the Isle of Man TT; but the FIM still rates the 588cc-

chamber-displacement rotary a 1200, which rules it out of most international racing classes.

But the most impressive new model, according to Le Roux, will be the street-legal derivative of the Norton rotary racer, a machine he expects to debut at the Cologne show in September. This latest Norton café racer should produce 100 horsepower and weigh well under 400 pounds, with styling that Le Roux describes simply as “exciting.”

The best news in all of this for Americans is that these Nortons should soon be offered in the U.S. Le Roux says that 49-state air-pollution standards are easily met by Norton’s latest engine, and even meeting the tougher California standards causes only a slight decrease in power. Currently, Le Roux is exploring U.S. distribution and dealer channels for Norton, and hopes soon to have an American presence.

In the meanwhile, information on Nortons can be obtained directly from the factory at Lynn Lane, Shenstone, Lichfield, Staffordshire WS14 OEA England; phone(0543)480101.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue