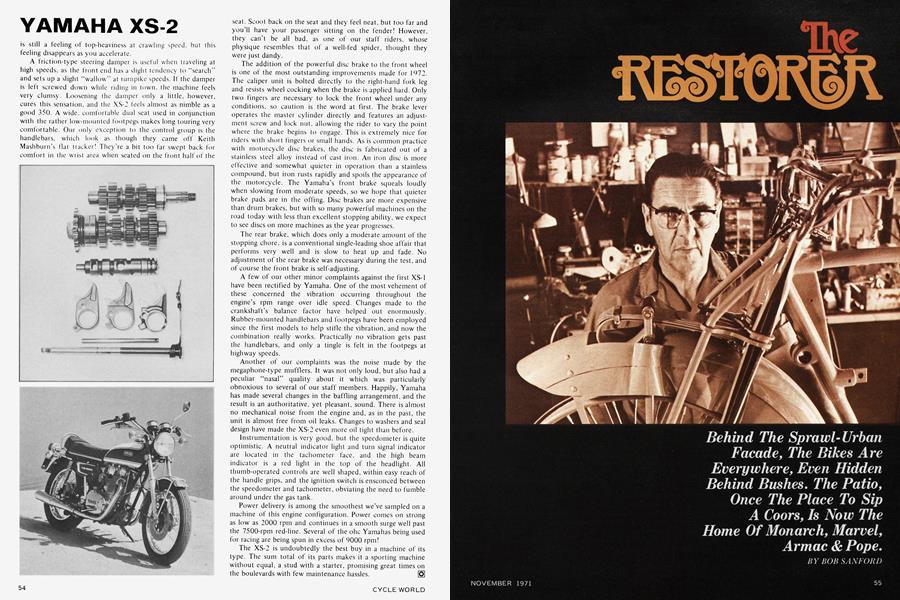

The RESTORER

Behind The Sprawl-Urban Facade, The Bikes Are Everywhere, Even Hidden Behind Bushes. The Patio, Once The Place To Sip A Coors, Is Now The Home Of Monarch, Marvel, Armac & Pope.

BOB SANFORD

OFF IN ONE dark corner, tightly wedged between a Cleveland and a Reliance, you spot the word THOR scripted across the rectangular gas tank of a somewhat rusted, yet amazingly complete, motorcycle that looks more ancient Schwinn than early Harley, and you ask Lyle Parker about the bike’s origin. Oh yes, he tells you. that one was made by the same company that built the washing machines. In about 1903, he says, Thor decided to get into the motorcycle business, and . . . etc., etc., etc. Lyle Parker, you see, knows all about pre-1920 American motorcycles. In fact, he is regarded by many to possess the Definitive Word concerning such machinery.

And if you don’t believe it, visit his home sometime. Or rather, his garage and backyard.

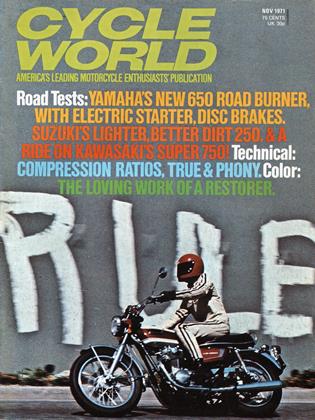

Having heard tales of the vast and valuable Parker collection of antique motorcycles, you arrive at the address jotted down on a notepad, and recheck the street and numbers, not quite believing that the small, unpretentious, middle-class, stucco, tract home in the small, unpretentious, middle-class town of Downey, Calif, could possibly house what may well be the world’s best and largest collection of pre-World War I American bikes. But Dorothy Parker, who answers the door, assures you that there is no mistake and that her husband is back in the garage with his Loved Ones. 3

Lyle Parker is a little too old to ask his exact age, and furthermore he has one of those faces that has weathered well and defies chronological assessment. Middle aged, to be sure. Maybe 50. Maybe more, maybe less. For whatever it’s worth, you fin(J.otit later he is twice a grandfather and that his own grandfather was a full-blooded Comanche Indian. He is standing next to his workbench fiddling with some parts from the 1915 Excelsior that he is

currently restoring. He shakes hands and smiles warmly, and it occurs to you that he does not seem to even notice that his black, slightly graying hair is considerably shorter than yours. His Sta-Prest jump-suit is amazingly clean for someone doing mechanics and looks like it was just pulled from the automatic washer, which is one of about three non-motorcycle things that take up space in the garage. Immediately, he starts talking about his bikes, pointing to the unrestored, yet very immaculate, 1912 belt driven Dayton Twin sitting alone in front of the garage. Did you know, he asks you, that the Dayton was made by the Davis Sewing Machine Co. in Dayton, Ohio? No, you didn’t.

The garage is literally wall-to-wall vintage motorcycle and paraphernalia. Center-stage is the Excelsior project, partially suspended over a workbench by a clothes line secured to the ceiling. The project is a long way from being complete, but you get your first inkling of Lyle Parker's devotion to detail, as you inspect the perfect, exact-shade-ofgray paint job on the chassis, and the beautifully chromed hubs, spokes and wheels. There are perhaps 10 other machines in the garage in various states of repair, including a nearly restored 1912 Pierce-Arrow. The back wall is completely lined with box after box of spare parts, some cataloged, most not. If you know where to look, you can find a brand new, still-wrapped-in-tissue-paper century gas taillight. Near the entrance there is a large lathe that Lyle Parker uses to fabricate missing parts that he can’t buy. And all across the floor are tools and parts and cans of every conceivable kind, use and description. But there is more. Much more.

Somehow, the Parker’s have managed to retain the semblance of a backyard, complete with neatly mowed dichondra. But all around the periphery, in hastily constructed sheds, under canvas covered lean-tos, and even hidden behind bushes, are bikes and parts and more bikes and more parts. What was once a patio for relaxing and sipping a cool Coors, is now home for such well known makes'of two-wheeled machinery as Monarch, Marvel, Armac, Neracar and Pope. And in a wooden shed attached to the end of the garage sits a huge pile of at least 40 engines, somewhat reminiscent of your neighborhood junk yard. But it's not junk. No indeed. Lyle Parker has painstakingly found and purchased each dirty, oil stained chunk of metal in the pile. Some he has use for, some he will trade and some are just plain nice to own. And very rarely, if the mood strikes him and he feels the prospective buyer is sincerely interested in antique bikes, he will sell one.

Where, for god's sake, Lyle, did you get all this stuff you ask? Did you find it in a barn? Oh, here and there, he says. Nothing in a barn, though. In fact, the only thing he ever found in a barn was horses and hay, he tells you, chuckling in a voice that makes you think he’s used that line a time or two before. Mostly, he says, he buys the bikes and parts from other collectors and at auctions and at regular meetings held by the antique bike people. Of course, he adds, when he travels, he never fails to ask local gas pump jockeys if they know of any “old-time motorcycle nuts.” And, occasionally, he finds things that way. For a price, of course.

How many bikes do you have, all told? He really doesn’t know, he says, shaking his head. He’s lost count. Well, how many brands? Twenty-two, he replies without hesitation. But, he points out, that’s really a drop in the bucket, since there have been more than 200 brands manufactured in the United States. 200? Right!

Which is one of the main reasons for his collection. Lyle Parker, you must understand, is somewhat disappointed that Americans are buying so many

foreign products. Not in the usual Love-1 t-Or-Leave-11. Buy-American sense, though. Mainly, he is disappointed that good quality American products are no longer available to Americans. He agrees, for instance, that it would probably be stupid to buy a Pinto instead of a Volkswagen. But he wishes that an American equivalent to the VW were available. The same thing for motorcycles. Kids today, he says, think that the Japanese invented the motorcycle, when, actually, there were some 150 American firms making bikes in 1915! So what he wants to do, he tells you, is open up a museum to honor early America’s motorcycle industry. To kindle remembrance of America's ingenuity.

You can’t help but feel, though, that the museum business is only part of the explanation for Lyle Parker’s collection, and is, perhaps, even a recent idea. First of all, Lyle Parker is A Collector. He just likes to collect things. Anything. Were circumstances different, he might be collecting, say, antique gambling devices. Until a few years ago, in fact, he was an avid gun collector, and still retains more guns than many enthusiasts, although he’s sold most of his collection. Along those same lines, he is one of those people that must have something to do to occupy his time. Just making a living, he tells you, is getting so complicated that it isn’t worthwhile. And, he adds, if he didn’t have something to do when he got home from work (production manager for a plastics firm) he’d go crazy. Secondly, Lyle Parker is a relative newcomer to the field of antique motorcycles, purchasing his first old machine in 1964, when he finally abandoned his long-time plan for restoring an old car and settled on a 1934 Indian. (He’s always been mechanical, he tells you, and had to have something to do.) He got such a bang out of it, he says, that he started buying everything that was the least bit old and had two wheels. Finally, he> realized “he couldn’t buy everything,’’ and sold all of his “new” (after 1940) equipment and began to concentrate on pre-1915 bikes. Which is where he’s at today, some 50 bikes and god-knowshow-much-money later.

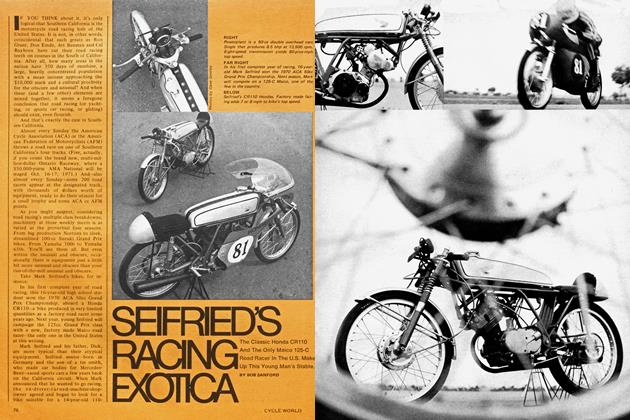

This 1915 Pope featured a single cylinder, automatic inlet valve, 26 in. displacement engine, which produced 4 bhp. It has a single speed transmission with an eclipse clutch and power is carried to the rear wheel via the leather belt. Lubrication is total loss and conducted by a drip-feed system, activated with a hand pump. There are no oil rings and two compression rings. The Pope gets about 65 mpg.

Like the 1915 Pope, the Flying Merkel is another single cylinder, belt-driven, single speed machine. The engine, however, uses ball bearings instead of bushing. Chassis design on the Merkel incorporated some surprisingly modern features—including swinging arm rear suspension system— which was later copied by Vincent. Ironically, the Merkel swinging arm system was scoffed at by other manufacturers and it was several decades before it came back into use. 1915 saw the demise of Merkel which was caused by bankruptcy resulting from numerous lawsuits over an extremely faulty automatic, spring-wound starter.

Motives aside, Lyle Parker has to be one of the most devoted members of today’s two-wheeled world. A goodly portion of his machinery is operable, and he is a firm believer in riding what he owns. He has, for instance, ridden one of his rigid-frame (he calls them “hard tails”) little belt-driven machines over 100 miles of pavement in one day. (Which is nothing compared to what he intends to do in the future.) And on weekends, he rides around his neighborhood. somewhat to the chagrin of his wife, who declares that the place is like “Grand Central Station” on Saturday and Sunday, when the aficionados and downright-curious gather at the Parker residence to talk shop and admire the machinery. Even while you’re there, a few people stop in front of the house to look at the strange, beautifully restored bikes that are sitting on the lawn. And Lyle Parker, you notice, seems quick to start conversation, patiently and cheerfully explaining the origin and finer points of the various machines to the uninitiated.

Perhaps more than anything, though, Lyle Parker is a purist and has some very strong negative feelings about people who collect and restore bikes for commercial gain, although he declares that if they want to do it. that’s “their business.” He also frowns on less-thanperfect restoration jobs, and, as indicated earlier, refuses to sell or trade to people he doesn’t feel are sincere and will not do a First Class job of putting the machinery back into near-original condition. On the other hand, he is more than willing to dispose of unneeded parts and bikes to people that he feels are dedicated. He helps them all he can. he explains, hoping to get more and

more people involved in collecting and restoring. As you might expect, he is a member of the Classic & Antique Motorcycle Association (CAMA), and has won numerous prizes at their regular get-togethers, including 1st and 2nd prizes for Best Restored Machine at last year’s meet in San Diego.

In a manner of speaking, you begin to suspect that one of Lyle Parker’s primary interests has precious little to do with 1915 nuts and bolts. He is very much interested in the people involved with the bikes, both past and present (you notice almost immediately that he has an uncanny ability to remember names, even of people he met only briefly several years ago). He is adamant that the nicest people he has ever met are collectors of vintage motorcycles. And he is full of anecdotes (and a few fantasies) about the previous owners, builders and riders of his bikes. He tells the story, for instance, of the time that the head of the Excelsior factory personally destroyed all of the company’s racing machines with a hammer, after their star factory rider, Bob Perry, was killed during a race at Ascot in 1919. And he is convinced (although he has no proof) that one of his machines with a 1918 license plate belonged to a soldier who went away to World War I and never returned.

Perhaps, though, his current project best exemplifies Lyle Parker and his hobby (or, Life Style). The Excelsior and the Rodgers sidecar that he is presently restoring will be used to transport him and his wife on a trip, hopefully with several other Excelsior owners, to Chicago, 111., home of the Schwinn Bicycle Co., the firm that earlier this century made the Excelsior.

“It’s just something I’ve got to do,” he says.. And after you’ve spent the better part of the day listening to Lyle Parker almost reverently describe his bikes and friends and life, you know that it is. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Round Up

Round UpLess Sound More Ground

November 1971 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1971 -

Departments:

Departments:"Feedback"

November 1971 -

Departments:

Departments:The Service Dept

November 1971 By Jody Nicholas -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

November 1971 By Ivan J. Wagar -

...Elsewhere On the Preview Circuit

...Elsewhere On the Preview CircuitHarley-Davidson Lays It On

November 1971