ONE HOT HARLEY

Under the paint and on the gas with Scott Parker’s XR750

BY DAVID EDWARDS

JUST MAKE SURE YOU KEEP IT out of the freakin’ wall.” That earthy advice was administered in 1977 by one Jay Springsteen to then-Test Editor Ron Griewe, just before Griewe climbed aboard the Springer’s Harley-Davidson XR750 dirt-tracker. Springsteen was not smiling, nor did he use the word “freakin’.”

Thirteen years later, Griewe passed the same raunchy recommendation on to me just before 1 climbed aboard a jetliner, bound for Milwaukee and a date with Scott Parker’s XR750, fresh off its 1 990 championship-winning season.

Not that I needed to be any more nervous about riding the orange-andblack, number-one Harley than I already was. My entire flat-track experience consisted of taking photos

and notes from the safe side of Turn One, and as I clomped around the office in my virginal Ken Maely steel shoe, feeling very much like Junior dressed up in Daddy’s wing tips, I wondered just what I was getting myself into here.

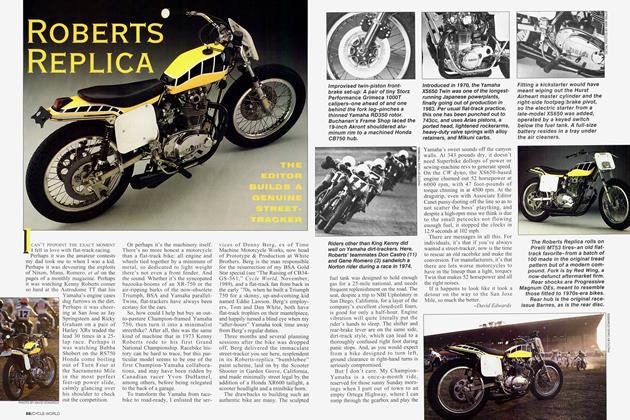

“No problem. It’s just like riding a Sportster. Really.” The words came from Bill Werner, the man responsible for the mechanical end of winning the national title. The XR75Ü, looking as purposeful as a snubnosed .38, rested in the pits at Marshfield Super Speedway, a half-mile, semi-banked clay oval smack-dab in the middle of Wisconsin.

Just like a Sportster, eh? Well, if you took a Sportster, threw away the frame and replaced it with a collection of 4130 chrome-moly tubes welded together by frame builder

Terry Knight, lopped off, oh, about 1 50 pounds of extraneous weight, allowed the engine to rev past the Sporty’s 6000-rpm redline to 9200 (doubling the horsepower to almost 100 in the process), fitted an upsidedown fork, Morris magnesium wheels, Goodyear tires and lightweight bodywork, then moved the rear brake lever to a position just beneath the right-side shifter and deepsixed the front brake altogether, then, yes, it was just like a Sportster.

Still, when Bill Werner talks about flat-tracking, people listen, and I was no different. At 46, Werner is the sport’s preeminent tuner. At one time a Class C rider who “won a few races, but mostly busted my butt,” Werner came to realize that he was better with a wrench than with a throttle. ^Already a lower-level me-

chanic in the Harley race department in 1 966, he moved up the ladder, and by 1974, was preparing Gary Scott’s bikes. The duo won the Grand National Championship in 1975. before Scott left the factory in a huff and went privateering. Werner was then paired with the up-and-coming Jay Springsteen, resulting in a string of three titles. In 1985, Werner teamed up with Scott Parker, and another title hat-trick followed in '88, '89 and '90. All together, Werner-prepped Harleys have won a phenomenal 73 national races on the way to seven GNC crowns.

“What wins championships is having an action plan for the whole season, not just individual races,” says Werner. “At the beginning of each year, I know exactly how many nuts and bolts I'm going to have in my toolbox at the end.”

Bob Conway, Harley-Davidson race-team manager and Werner's boss, explains his employee’s success: “Total dedication. He gives 200 percent effort. If something goes wrong, he won't rest until it's not a problem anymore. Every nut. bolt, bracket and wire on that bike is there to solve a problem he once had. We had a gas line fail once and it cost us a race. Bill wanted to redesign the whole fuel system; he was almost unlivable for two weeks.”

Says Werner of his fastidious bike preparation. “Anybody can have some kind of a failure. If it happens more than once, though, it’s inexcusable. And. sometimes, even once is one time too many.”

About the bikes he frets over for 10 months of the year? “They’re Scotty’s motorcycles, but they're my easel, my canvas. I spend more time

with the bikes—60 to 70 hours a week—than I do with my family. They’re only nuts and bolts, but that’s me out there, my way of competing. All mechanics feel that way, whether they admit it or not.”

The XR I would be straddling was the team’s backup bike, much fresher than the battle-scarred warhorse that had carried Parker throughout most of the season. Still, the secondary bike was fast enough to have finished first at the Indy Mile, winning the Camel Dash and setting fast heat time, as well.

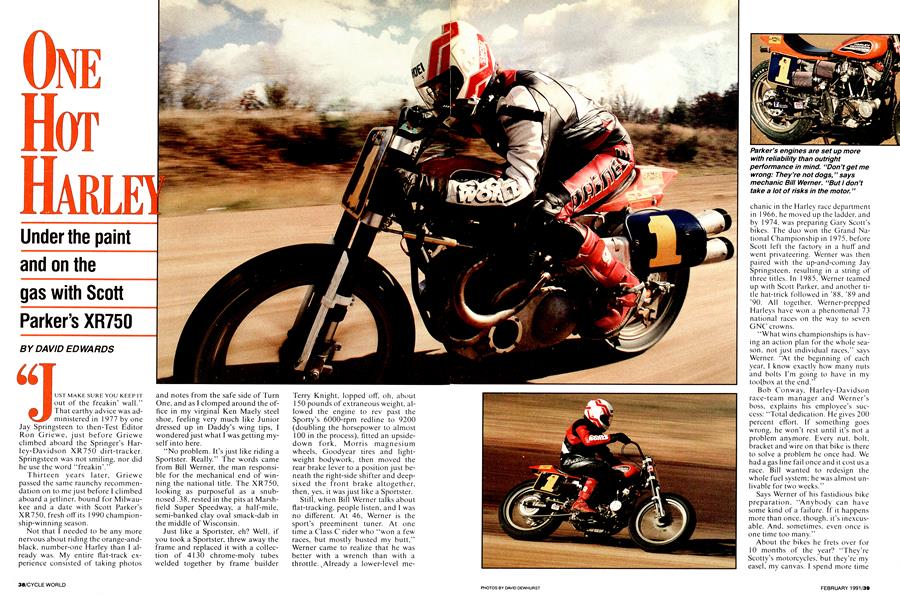

Before my first laps, Parker suited up and circulated around the track to warm up the engine, then reeled off 10 or so flying laps. Turns One and Two were still tacky-damp from recent rains and didn’t allow much sliding, but Three and Four, the recipients of more sunlight, were dry. Parker, without a crowd of Camel Pro riders nipping at his rear wheel, and without the pressure of having to set fast qualifying time, indulged in a little rim-riding, sliding the bellowing

XR around the outside portion of the track. After each pass, the disrupted dust would hang in the air as if it, like the rest of us watching, were staggered by Parker’s sheer riding ability.

“He’s awesome,” Werner says. “When everything is going right at a track, he can make the rest of ’em look like idiots.”

Scott Parker, 29, is becoming a dynasty in Camel Pro racing. In a sport that many have described as dying out, Parker toted home about a halfmillion dollars in earnings last year, counting salary, winnings, contingencies, point-fund money and bonuses. Only a few motocross racers and a handful of GP stars made

more. Next season, he could tie Carroll Resweber's record of four straight grand national championships (see “Still the Man to Beat,” below), and he needs only three more race wins to match all-time national winner Jay Springsteen’s total of 40. “Those are my goals. 1 want to be in the record books. I’m ready and Bill’s ready,” says Parker.

Soon, Parker came in and handed off to me, imparting a final bit of advice. “Make sure you don’t snap the throttle shut while it’s sideways,” he cautioned. I wanted to ask just what it was I should do if 1 got into trouble, but all 1 could think of was the famous line Graham Hill once used. “Calling upon all my years of experience, I froze at the controls,” he's reputed to have said after heavily wadding a Formula One car.

Well. I didn't freeze, but neither will I get a tryout for the next Team Harley opening. With Werner pushing, bump-starting the XR was easy, though 1 had to blip the throttle to keep the bike alive: The twin Mikunis have no idle circuits. Other than that, the engine was non-intimidating, pulling from low revs without a hitch —kind of like, well, a Sportster. What was disconcerting was the bike’s size, or lack thereof. With a

full-face helmet on, an XR rider sees little of the 320-pound bike he's riding besides the handlebar and the top triple clamp. Roll on the throttle in second gear and the front end is in the air before you know it, reluctant to come down, thanks to the engine's heavy flywheels.

While Parker could thunder around the track in top gear. I was happy to keep the gearbox one cog lower, in third. Even at that, it was

amazing how short a distance a halfmile can be. and how a corner viewed as impressively wide from the grandstands can take on the proportions of a scrawny driveway when seen from the saddle of a speeding flat-tracker.

And what happens when you bang the throttle shut in mid-turn, I found out despite Parker's warning, is that the bikes snaps upright, the front end starts plowing and you head straight towards the edge of the track. Reap-

plying the gas brings things under control, until you timidly let off again and cause the whole ungainly process to repeat itself. In 30 laps of trying, I never did put together one smooth, continuous, corner-long slide, though I did manage to give myself The Charlie Horse From Hell, my left thigh unaccustomed to supporting the extra weight of a steel shoe, not to mention the responsibility of holding a sliding XR750 upright.

My faltering laps did give me some insight into the reason that American ex-dirt-trackers like Kenny Roberts, Eddie Lawson and Wayne Rainey became dominant on the world’s roadrace tracks, though. Even stuck in third gear and going all of 80 mph, it was easy to comprehend how backing a flat-track bike into the 100-mph corners of a mile oval, throttle-balancing the slides of both tires and persuading every last ounce of traction out of a bucking motorcycle to get the killer drive down a straightaway, has to be the best training in the world for future GP heroes.

On a sunlit autumn day on a backwater track in Wisconsin, though, a clumsy journalist was satisfied just to be on the other side of the fence, even for only a few laps, twisting the throttle, reveling in the roar and being pulled along by a hundred-horsepower handlebar. I came away beaming, with an insight into the trenchant

hold that this type of competition has over its riders.

The next day, Griewe stuck his head into my office. “You lived, huh? How was it?” he asked.

“It was,” I said, choosing my words carefully, “freakin’ fantastic.”

And I didn’t use the word “freakin’,” either. E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAscot Eulogy

February 1991 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeDoin' the Norton Rap

February 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsLetters From the World

February 1991 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1991 -

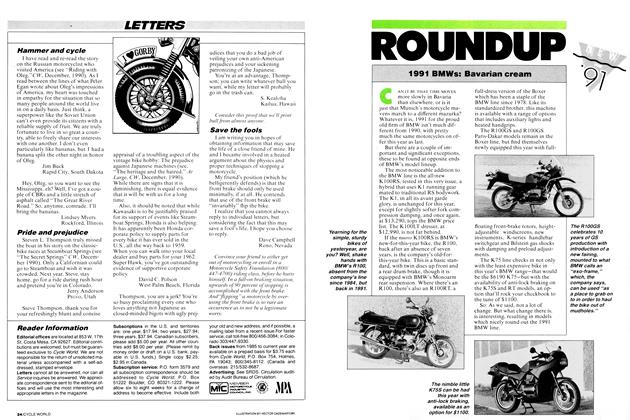

Roundup

Roundup1991 Bmws: Bavarian Cream

February 1991 -

Roundup

RoundupCzeching Out Jawa

February 1991 By Pavel Husák