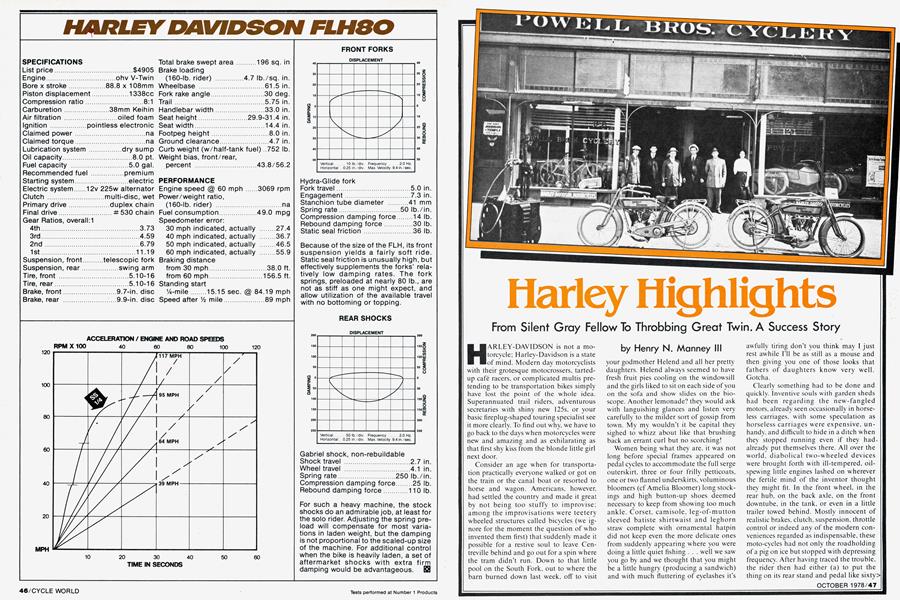

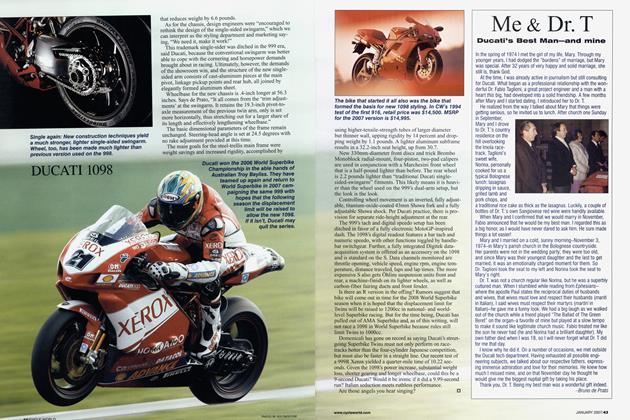

Harley Highlights

From Silent Gray Fellow To Throbbing Great Twin. A Success Story

by Henry N. Manney III

HARLEY-DAVIDSON is not a motorcycle; Harley-Davidson is a state of mind. Modern day motorcyclists with their grotesque motocrossers, tartedup café racers, or complicated multis pretending to be transportation bikes simply have lost the point of the whole idea. Superannuated trail riders, adventurous secretaries with shiny new 125s, or your basic fireplug-shaped touring specialist see it more clearly. To find out why, we have to go back to the days when motorcycles were new and amazing and as exhilarating as that first shy kiss from the blonde little girl next door.

Consider an age when for transportation practically everyone walked or got on the train or the canal boat or resorted to horse and wagon. Americans, however, had settled the country and made it great by not being too stuffy to improvise; among the improvisations were teetery wheeled structures called bicycles (we ignore for the moment the question of who invented them first) that suddenly made it possible for a restive soul to leave Centreville behind and go out for a spin where the tram didn’t run. Down to that little pool on the South Fork, out to where the barn burned down last week, off to visit your godmother Flelend and all her pretty daughters. Helend always seemed to have fresh fruit pies cooling on the windowsill and the girls liked to sit on each side of you on the sofa and show slides on the bioscope. Another lemonade? they would ask with languishing glances and listen very carefully to the milder sort of gossip from town. My my wouldn’t it be capital they sighed to whizz about like that brushing back an errant curl but no scorching!

Women being what they are, it was not long before special frames appeared on pedal cycles to accommodate the full serge outerskirt, three or four frilly petticoats, one or two flannel underskirts, voluminous bloomers (cf Amelia Bloomer) long stockings and high button-up shoes deemed necessary to keep from showing too much ankle. Corset, camisole, leg-of-mutton sleeved batiste shirtwaist and leghorn straw complete with ornamental hatpin did not keep even the more delicate ones from suddenly appearing where you were doing a little quiet fishing . . . well we saw you go by and we thought that you might be a little hungry (producing a sandwich) and with much fluttering of eyelashes it’s awfully tiring don’t you think may I just rest awhile I’ll be as still as a mouse and then giving you one of those looks that fathers of daughters know very well. Gotcha.

Clearly something had to be done and quickly. Inventive souls with garden sheds had been regarding the new-fangled motors, already seen occasionally in horseless carriages, with some speculation as horseless carriages were expensive, unhandy, and difficult to hide in a ditch when they stopped running even if they had. already put themselves there. All over the world, diabolical two-wheeled devices were brought forth with ill-tempered, oilspewing little engines lashed on wherever the fertile mind of the inventor thought they might fit. In the front wheel, in the rear hub, on the back axle, on the front downtube, in the tank, or even in a little trailer towed behind. Mostly innocent of realistic brakes, clutch, suspension, throttle control or indeed any of the modern conveniences regarded as indispensable, these moto-cycles had not only the roadholding of a pig on ice but stopped with depressing frequency. After having traced the trouble, the rider then had either (a) to put the thing on its rear stand and pedal like sixty> to make the engine fire (b) run and bump (c) push home (d) load it in the back of a convenient wagon. Clearly this was a pursuit for only the strongest and most athletic of men. let alone ribbon clerks and other assorted pooves. The ladies, encumbered with full serge skirt, three or four frilly petticoats ad lib. only pursed their lips and waited.

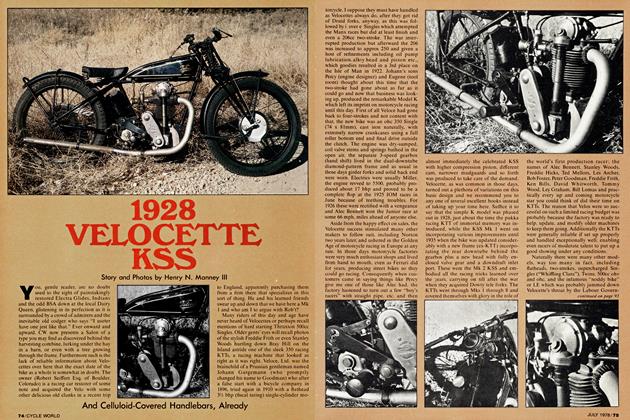

Mr. Harley and Mr. Davidson thought that there must be a better way. Calling in two other Davidsons who also owned the peculiar skills suitable for building motorcycles, they painstakingly constructed a flimsy, rather gutless De Dion-based Single in 1903 which obviously wasn’t The Way either. Back to the old drawing board, the team produced a 3 hp, 25 cu.ia Single (3-5/16 X 4) with engine in the “Werner position” and beefed-up frame that was more like it; in fact, the new HarleyDavidson Company sold all its production run (3) of the Silent Gray Fellows in that first banner year. Slowly the factory found its feet and before long was turning out 50 or more in a year, their solid construction and relatively trouble-free running all too prominent in those days of any old rubbish being marketed. The Harleys and Davidsons did their homework well with such modern devices as alloy crankcase, loop frame and sophisticated belt tensioner (as a sort of a clutch) on those highboy pocketvalvers; some 100,000 miles later the first “production” example was still running. Other factories such as Indian, however, were progressing faster and the cry soon went up from dealers for Speed! More Speed! Harley replied in the classical fashion of those days by simply adding another cylinder to make a 53.68 cu. in, 45 deg. Twin (does that sound familiar?) which by the time America entered the Kaiser War had accumulated such refinements as a proper clutch, sheet metal primary chain case, mechanically operated intake valves, centre-post sprung saddle of immortal memory, the much-copied bottom link front forks (first on the Single), coil ignition as an option, chain drive ditto, kick starter, internal expanding rear brake, and three speed transmission, none of which were absolutely shattering advances engineeringwise but certainly made life easier for the rider. Actually the American factories, at least the larger ones, were quite conservative compared to designers on the other side of the Atlantic who had tried swing-arm suspension, disc brakes, foot change, a form of telescopic fork, pressure lubrication, overhead cams and even a Wankel-type engine very early on indeed! However, the needs of our motorcyclists were a bit different than those of England, say, with roads largely unimproved to put it mildly out of the cities, cheap gas. and much longer distances to cover without often any human habitation. The long-legged V Twins thus developed even became a cult in some foreign countries due to their lack of fuss. Some early issues of Pacific Motorcyclist (1913-14-15) lent to me by the Rev. Joe Parkhurst give the flavor of these early days in a way that any number of faked-up TV documentaries cannot. One issue speaks of a club run from LA to San Jose and back featuring “adobe” roads (very slippery when wet), drift sand, fords, and craters where the highway had just gone away, as happens occasionally in California’s winter. Mileages were not high as a lot of time was spent nattering, trouble was usually confined to punctures or broken drive belts, and the worst panic (besides the support car falling off a cliff) came when everyone stopped for the night at Paso Robles to find out that it was a “dry” town. Yes. the ladies came too. Another issue speaks of a desert race from San Diego to Phoenix at a time when there simply weren’t any roads . . . just cowtrails I suppose . . . over most of it. Indian was the big runner at this time with Thor, Excelsior, Yale, Cyclone, etc. close up and Harleys being regarded sort of like Plymouth Sixes in the Forties; reliable but not very exciting. Feature if you will struggling across the mountains and up through the blowsand dunes near Yuma on and off the deteriorated Old Plank Road, or through five miles of Mammoth Dry Wash before teetering along a railroad trestle across the Colorado, hoping the train wouldn’t appear. All this on a single-speed Indian popper, looking like a corncob on a rock, with what amounts to no brakes and bicycle tyres. At least that’s what the winner. Lorenzo Boido, rode.

Wars, whatever their negative feedback, tend to be looked upon by both politicians and industrialists as a source of graft as well as accelerated technical development. Aircraft engines, for example, went from agricultural flatheads through those odd rotaries to comparatively sophisticated ohv V8s before the Armistice rolled around. Harley of course had already shown its worth by furnishing big Twins (or even the 5-35 Single) as despatch mounts in the banana wars so practically all of the factory’s production went to the AEF for service. In the bottomless mud of Flanders, anything that could break did break and the factory engineers filed all this information away, rejoicing meanwhile that the “colonial” roads of Middle America had forced them to build a solid motorcycle in the first place.

Given the strides in metallurgy and engine design, one might expect Harley to come out with something completely different and so they did in 1919. a fore and aft flat Twin drawing its inspiration from the Douglas (GB) which also had been a successful despatch machine. This new Twin of 37 cu.in. featured such niceties as enclosed chain final drive, full electrics and easy starting, obviously being pointed at the ladies’ market (skirts were shorter, too!) but after a few years died an unlamented death. Many reasons have been advanced for this demise, among them the superior performance of the concurrent Indian Scout or the bother of setting up a separate production line (although I am sure many parts were interchangeable with those of the Twins or even the Singles that Harley kept trying in depression times) but looking back on my early days in motorcycling, the real reason was that no grown man wanted to be seen on anything but a big V Twin. Even if it were khaki, as the factory must have had millions of gallons of o.d. paint left over. The W series 45 cu.in. sidevalve V Twin, developed for the AEF but too late for the war I think, appeared also in 1919 and showed the way things were going to go chez Harley, thus commencing the 45’s long reign. Shortly afterward the 61 cu, in.Twin (inlet over exhaust valves) was joined by a bored and stroked 74 of the same configuration. On the face of it, a sidevalve engine seems less efficient than one with an ohv but on the older i over e design, the inlet valve lives in a little house of its own (sometimes the exhaust valve as well; see Daimler) supplying fuel through a tunnel. There are many reasons for this, including the frequent tendency for early valves to stick or break off, sketchy lubrication, ease of redesign from the earlier atmospheric inlet valve, poor fuel, ditto carburetors, and lack of research into combustion chamber behavior. The forced draft R & D into aircraft and racing car engines (this is well after when the twin-cam hemispherical Henri Peugeots were running) apparently made no difference to Harley ... or Indian for that matter ... as H-D’s next step in 1930 was to produce the 74 sidevalve (flathead) VL Twin, probably the best motorcycle Harley ever made. During my service in the Wah (under Stonewall Jackson? . . . Ed.) it was the accepted drill, on moving to a new base, to shop around for a used bike and as Indian owners used to guard theirs like gold, perforce the choice was from a selection of prewar VLs. Provided both wheels ran in the same direction and they started third kick, money changed hands and freedom was mine for $100 or so, the standard price for these old harvesters. I knew absolutely nothing about machinery at that time and don’t recall even wondering what points, plugs, valves, pistons etc were, let alone actually touching any of those objects. The rider put gas in the gas tank, oil in the oil tank, and gave that little oil pump handle on top a shot or two during those hundred mile runs to civilization. Nothing ever went wrong or fell off and the VL uncomplainingly accepted any old drain oil or for that matter avgas filched out of B-29 tanks which really cleaned out the exhaust system wonderfully with a great display of sparks. When you were transferred. say, from Alamogordo to Florida with enough travel time, you went round it with an oil can lubricating anything that looked as if it moved and then took off, usually with some unfortunate on the back. I did that once in company with another GI; despite some hard starting due to a day-long rainstorm, the only trouble we had was a broken chain which a passing civilian rider fixed. We didn’t know what a master link was. In those days all riders were in it together and even if you saw an Indian broken down, you stopped to see if some assistance could be offered. Not like today. There was very little traffic and no cops outside of the towns and no mass of ch*ck*nsh*t rules about riding sideways on the bike or even backwards if you felt like it. The post solo saddle was more comfortable, of course, for short runs but we felt that the ironing board “buddy” saddle (often with sheepskin cover) was better for long trips as the rider could move around a bit. With the peculiar muffled beat of those big flatheads and the tranquillizing rockinghorse gait typical of vintage machinery, it was sheer bliss to cover several hundred miles even across West Texas. The long bars, footboards, rigid frames, hand shift etc look awkward today but I don’t recall being really uncomfortable. Of course I was younger then.

Generally speaking. basic motorcycle transportation for the lower orders (us) was furnished by 74 VLs which was always a bit of a surprise as I always understood that Indian production had been greater than Harley’s and Indian shops appeared with great frequency. Harley dealerships in those days were havens of rest where you could have a cold Nehi, talk with the folks, and stand around listening to the incredible tales that you still hear at Harley shops. Opened-up-to135-cu.-inches-do-a-hunnert-and-fifty-this-old-farmer-come-outtowing-a-trailer-I-laid-her-down-went-under-the-towbar-finished-up-in-a-big-pileof-cow-flop-not-a-scratch-on-her and so forth. Visitors to Harley shops today will hear the same stories from the same sort of people and it is nice to know that some things haven’t changed, even if you can’t go stand around among the mechanics any more lest the service manager (!) complain. Occasionally, some rake-hell would appear on the remarkable, glittering, glamorous, and to our eyes fiendishly complicated 61 overhead (introduced in 1936) which was, by Harley standards, all a brand new design with proper oil circulation at last (although they must have had it on the ohv Singles in ’35 . . . see Petrali’s Peashooter . . .), one cam working the staggered pushrods, four-speed transmission and a lot of other things taken for granted today. With a little tweaking the 61s would do an honest 100 mph and such was their reputation plus their dissonant, jangling mode of passing that they tended to attract the sort of kid who wore his cap backwards. NO nice girl would be seen on one. Naturally, the new owner’s first move was to remove the muffler’s innards, which gave the 61 a noise level like a Sherman tank with loose tracks, and I remember talking to a 61 owner whose bike had spent 30 days in a Georgia jail for buzzing the town. Anyway, Harley being what it is, the bore and stroke stayed the same as that on the original i over e 61 and I wouldn’t be surprised if a lot of other bits were the same as well. According to Mr. Nielson of Harley’s Engineering Dept, (yes, Virginia. . .) the V Twins have had roller bearing bottom ends and the forked rod setup since the first one and inasmuch as concrete Harley information is notoriously hard to come by except that vague stuff issued by the factory (I refer you to Hendry’s book on Harley-Davidson if you can find one) we have to take it at that. At any rate, public acceptance of the 61 ohv was followed by the appearance, in 1937, of the 80 ... an enlarged 74 flathead . . . while sundry modifications to bring the older models up to 61 mechanical specs such as aluminum heads, four speeds and superfat tyres were offered; mostly as options as the twin afflictions of cheap cars and the depression cut into motorcycle sales. Not until 1941 did the ohv 74, papa of today’s Electra-Glide, make its appearance.

Racing has been an integral part of Harley history since 1914 or thereabouts, when in response to the successes of Indian et al the factory decided that racing was likely to pay dividends in both develop-> ment and sales. Racing designer William Ottaway was hired away from arch-enemy Thor, crack riders like Otto Walker. Red Parkhurst, Ralph Hepburn, etc were put under contract to commence the “Wrecking Crew” and the hunt was on. A lot of the early running before the Kaiser War was on banked board tracks, high-speed devices made hurriedly out of God knows how many 2 by 4s laid on edge, and the perils of this sort of competition are illustrated not only by Mr. Beardsley’s articles on the subject (see old issues CW) but also the graphic nickname of Glen “Splinters” Burke. Lapping at 100 mph on these unsanitary pistes with nailheads, rough joints, and sudden changes of camber where the banking came in (not to mention oil puked out by the total-loss engines) would be a bit alarming on a well-sprung, well-shod Harley today, let alone some weaving device with more engine than frame and bicycle tyres. The rough dirt tracks of the Midwest, storied Dodge City and the others, weren't much better what with their paralysing heat, potholes and dust. Covered with success, the factory “officially retired” their racing team in 1921 but the racing went on of course, the quick boys getting bikes, parts etc from the factory while everybody else raced for love and the hopes of making a few bucks to continue racing. It was a hard, hard life and only the hardest among them continued in this peculiarly American sport, its roots in pickup races between the pioneers’ choice saddle horses. A lot of Harley’s conservatism and love of status quo stem from these days as only the most solid construction, that tested by time, could hold the pace. Fast ein,Kt wo,',o,-c were sent out to act as rabbits while the slower, but more reliable pocket-valve twins were counted to finish after the “cracks” had blown up. For years the favored wear on dirt tracks was the rigid framed K series 45 cu inch v twins and it was just over ten years ago that the hoary flathead. dragged up to 60 hp by dint of relentless development by racing manager Dick O’Brien, gave way to an overhead valve setup. Some flatheads are still running on small, loose tracks where they are deemed to give a better bite.

Old issues of CW make fascinating reading and especially so in the case of the June 65 issue which has a nice story by Gordon Jennings (yes, he used to be Tech Ed here) on development of the 45 cu in flathead. especially in respect to competition at that time. I wish we had the space to reprint the whole article from a historical point of view as Harley, for reasons connected with the prevailing AMA racing formula, must have been the last people in the world doing development on flatheads. The article is too good to cut up with a précis but basically what is demonstrated is a combination of high-class empirical engineering by tuner Jerry Branch plus a lot of trick work on the heads and induction passages. As normal gasoline was used, the c.r. rarely rose above 6.5:1 which is laughable by proper racing standards but you must remember that the flathead (or sidevalve) engine is an obstinate device. What Harley was after was torque, mostly, (although the engines were safe up to 7600) for the shortish dirt tracks with long curves. A friend of mine was telling me about riding a WR for the first time on the half-mile after having blown up his Triumph or BSA or whatever it was; Harley’s competition at this time was limited to 500 cc ohv or ohc by AMA ukase. Anyway the owner warned Gene (Curtis) not to do anything strange whereas Gene gave it a big handful in a corner and promptly fell on his ear. No, said the owner, just get on and ride it around; let the WR do the work. Gene tried it and said that he never had a smoother or less fatiguing ride in all his life . . . forty years of development on that old turkey took out all the labour.

Chauvinism, for which read Home Town Decision, is nothing unusual in any country, as the colored boxer who knocked out an Irishman on St Patrick's Day in Dublin and lost the match found out. Since the demise of Indian, it was more or less common gossip that Harley "owned" the AMA and there were a lot of peculiar rulings that came out of that august body. In retrospect, however, the 750 cc flathead, vs 500 cc ohv or ohc worked out pretty well once Americans found out how to keep English production bikes (a Manx Norton is a production bike?) together and drag some horsepower out of them. Of course at that time postwar Daytona was the only really fast venue even with the beach course at first but there are those who say events like the San Jose Mile are faster, at least they feel faster. Harley managed to hold its own with some luck even up to the rule change which let everyone run 750s with ohv (see another CW article on head development for the ohv) but progress has passed it by on the increasingly popular road race circuits. On the dirt, of course, Harleys are practically unbeatable. The rot had set in by simple mathematics of piston area and overall weight even before the lighter two-strokes (especially Yamaha) re ally got going but who knows what wonders could have come about had not Harleys, baking every day to keep from baking for tomorrow, stuck with the flathead for so long? Nowadays the big Sportster can’t even come close to cutting it in the Production bike event. And you don’t run Sportsters or Electra Glides on the half mile.

Once Hitler was carbonisé and the Japanese (ho ho) were put where they couldn’t do any more harm Harley commenced to look over the situation. Clearly the world market would change as already before the War the Europeans had shown that they could make fast, maneuverable, raceworthy bikes which could even be somewhat reliable. Indian was already on the skids from a bad case of long-time poor frontoffice management, bad luck, and assorted dirty tricks (see The Iron Redskin by H.V. Sucher) which could be regarded as either an advantage to traditional enemy HarleyDavidson or a disadvantage, depending on what point of view one took. At any rate, Indian fell into the trap of trying to make a bike which other people could make better with their 220 Single and 440 cc Twin continental-type machinery; promptly laying the biggest egg since Sinbad’s roc. All this was not lost on Harley who contented themselves with ohv on the 74 which had barely got into production in 1941, hydraulic valve lifters as well, and then the telescopic Hydra Glide fork for a semblance of modernity. Anything that could roll, sold in those days but the market was further complicated by the masses (at first) of ex-WD 45s which promptly were painted in the most astounding colors by their new owners, all thoroughly sick of khaki. I had at that time one of the rare flat Twins, modelled on the little shaft-drive Zundapp I think, manufactured by Harley for the North African desert campaign and a nice bike it was too with foot shift, hand clutch, and oil bath air cleaner inside its cave. Unfortunately, I don’t think it would have managed much sand as not only was it a bit cumbersome on rough going but also tended, as the fins were rather short and Harley had stuck to side valves, to get hot enough so that the cylinders in the region of the exhaust ports would get more than a little pinkish when driven hard. Another oddment, although HD Engineering claims it never existed, was an ex-WD 30.50 cu in (500 cc) model like the 45 cu incher scaled down. Hand shift, blackout lights, WD panniers, the lot. Little bitty cylinders. A first kick starter, great town bike, dead reliable. Has anyone heard of one like that?

The first English bikes started coming over and I remember standing with a bunch of other layabouts watching an early Ariel pogo gently about on its soft suspension going pop pop pop and muttering things like Nossir those light bikes don’t hold the road, a comment still heard from old ladies of both sexes. However, the ease of control of the foot shift shafty Harley still stuck in my mind and clearly the Americans, after such a war, were ready for something new and different. Sales of British bikes took off, sales of sports cars like the bone-jarring MG TC followed suit and Harley brought forth, a little ahead of its time or a little behind it, a 125 cc two-stroke on “continental lines” (possibly made overseas) which got itself telescopic forks a few years later. In spite of the disadvantages marketwise of cheap gas, lack of mixer pumps (as in Europe) and absolutely no performance the little two-strokes in various ramifications held on until after Harley made an arrangement with the Aermacchi plant in Italy to give itself a medium range of bikes, both two-stroke and four. The Aermacchi fourstrokes weren’t bad at all but nobody except the salesmen ever regarded them as Harleys. In any case, that little experiment has gone down the tube, the twin devils of labour troubles over there and a reluctance to put money into development probably being the answer.

More like it, to traditional Harley fans, were the new K series 45 cudnchers in 1952 fitted with a lower frame which was sprung at both ends. A further bow towards the 20th Century came with the fitting of footshift-hand-clutch mechanisms although I think that you can still get the traditional setup on special order. Anyway, faced with a shrinking slice of the market and insistent calls for performance, the factory soon bumped (in 1955) the long-suffering 45 up to 55 cu. in. (which the KH racers didn’t get to share) while two years later the venerable flathead design was finally flung out with the bathwater as the KH acquired ohv to become first the Sportster (XL) and then soon the racier XCLH . . . back to the magneto after thirty years. The Styling Dept (yes, Virginia. . .) has wrought some pretty unusual variations on the XCLH, pretty accurately aimed at what has been called the Café Racer Market but it is a bit bemusing to see a Mod Harley. The bigger Twins . . . well, not much bigger . . . have contented themselves with detail changes such as hydraulic brakes on the Hydraglide (1958), swing arm (1959) and then the Electra Glide with electric starting, and 12 volt system etc in 1966, a much appreciated move in most of our country as nobody really likes kicking over a big Twin on frosty mornings. Subsequent developments have been in the line of an alternator in place of the generator (although HD electrics have always been pretty good), hydraulic disc brakes and an insidious influx of Japanese parts into what used to be an All-American machine. The latest development (see test) is the ohv 80 which, though hardly modern (the crankpin has a 1941 part number) is a very comfortable touring mount and most Harley riders wouldn’t have it any other way.

In 1969, for various reasons probably not a million miles from capital reserves, the family corporation of Harley-Davidson merged/was bought out by/taken over by/came under the control of (check one) American Machine and Foundry, better known as AMF. From the uproar ensuing, one would have thought that the Pope had turned up in a Gay Lib parade wearing beads (he does wear beads. . . Ed) and naturally enough there were a lot of complaints about handwork at the Milwaukee plant suffering as a result of a transfer to the new automated plant at York, Pa. You do hear a lot of comments about a basket under the engine to catch parts being an optional accessory and old Harley riders do wag their heads sagely and say Ar they ain’t built like they useter be but then what is? Stories about Harley reliability or the lack of (“Harley-Davidson, made of tin. . .”) are as much of America’s folklore, especially to Indian owners, as Johnny Appleseed but motorcyclists have to talk about something standing around in the garage. Whether the prevailing abandonment of Harleys in favour of Japanese multis or Moto Guzzis by the motorcycle cops has anything to do with this merger either or whether just a question of price, I don’t know.

Harley sources claim that they own between 40 and 50% of the “big bike” market, whatever that works out to overall. They also seem to be confident and hint of marvelous things to come in the future even if many of us, looking at some of the technologically advanced designs coming out of other countries feel a little apprehensive about the big Twin’s survival. The sheer cost of tooling up or something completely new would be shattering for one thing at today’s prices, plus the conservatism of HD itself and an unwillingness to copy anyone directly so that the 1980 Harley, say, could offer a decent three speed automatic perhaps, overhead cams to cut down reciprocating weight, shaft drive (remember the WD flat Twin?), an improved gearbox, suspension that suspends and possibly even fuel injection which even cheaper cars have now. Still it would unmistakably be a Harley. Rolling peaceably down a long oak-lined road on a Harley in the early evening is one of the most pleasurable experiences known to man. Wuffle wuffle clank clank clank. Smells of the country. A wave to another Harley rider. The big Twin sounding as if it would go on forever. This is the way Harleys began and how, we hope, they will continue.Happy Seventy-Fifth Birthday!®

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontYou Can't Take the Harley Out of the Boy

October 1978 By Allan Girdler -

Departments

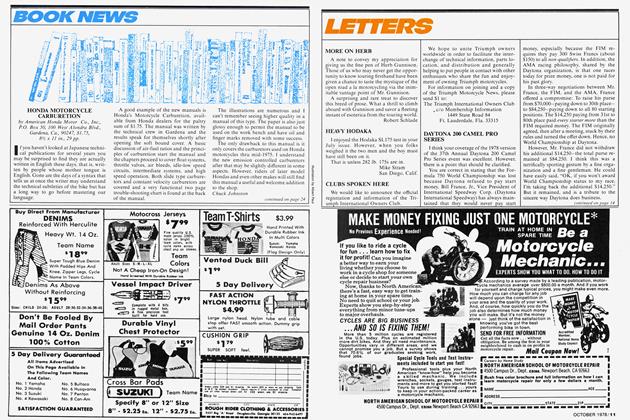

DepartmentsBook News

October 1978 By A.G., Chuck Johnston, Michael M. Griffin -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1978 -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

October 1978 -

Short Strokes

October 1978 By Tim Barela -

Technical

TechnicalYamaha It250/400 Steering Fix

October 1978 By Len Vucci