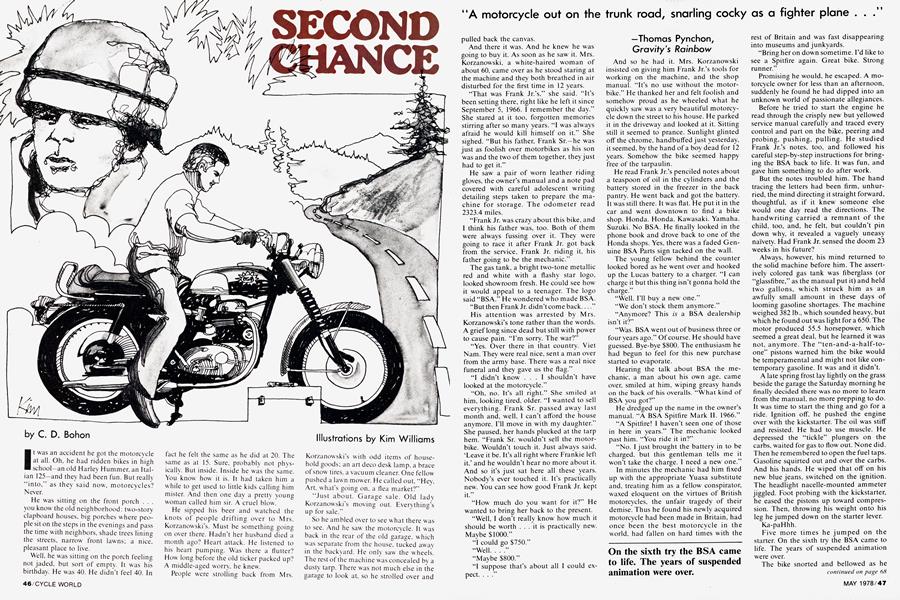

SECOND CHANCE

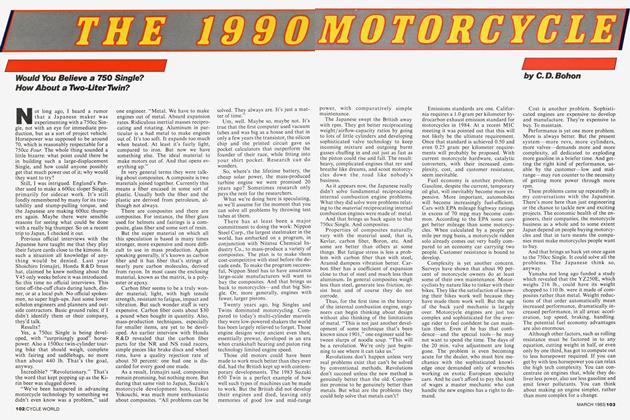

C. D. Bohon

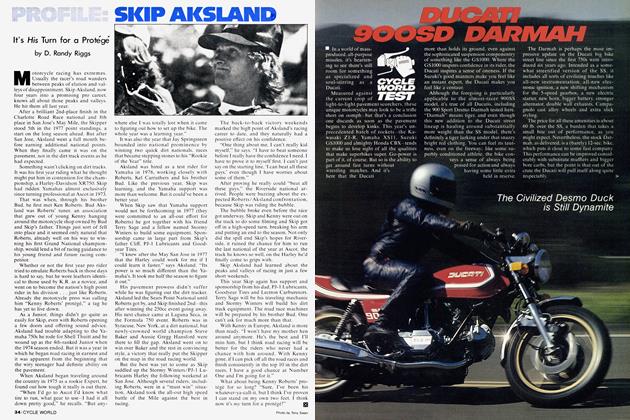

It was an accident he got the motorcycle at all. Oh, he had ridden bikes in high school—an old Harley Hummer, an Italian 125—and they had been fun. But really "into," as they said now, motorcycles? Never.

He was sitting on the front porch . . . you know the old neighborhood: two-story clapboard houses, big porches w;here people sit on the steps in the evenings and pass the time with neighbors, shade trees lining the streets, narrow front lawns; a nice, pleasant place to live.

Well, he was sitting on the porch feeling not jaded, but sort of empty. It was his birthday. He was 40. He didn't feel 40. In fact he felt the same as he did at 20. The same as at 15. Sure, probably not physically. But inside. Inside he was the same. You know how' it is. It had taken him a while to get used to little kids calling him mister. And then one day a pretty young woman called him sir. A cruel blow.

He sipped his beer and watched the knots of people drifting over to Mrs. Korzanow'ski's. Must be something going on over there. Hadn't her husband died a month ago1? Heart attack. He listened to his heart pumping. Was there a flutter? How long before the old ticker packed up? A middle-aged worry, he knew.

People were strolling back from Mrs.

Korzanowski’s with odd items of household goods; an art deco desk lamp, a brace of snow tires, a vacuum cleaner. One fellowpushed a lawn mower. He called out, “Hey, Art, what’s going on, a flea market?”

“Just about. Garage sale. Old lady Korzanowski’s moving out. Everything’s up for sale.”

So he ambled over to see w hat there was to see. And he saw the motorcycle. It was back in the rear of the old garage, which was separate from the house, tucked away in the backyard. He only saw the wheels. The rest of the machine was concealed by a dusty tarp. There was not much else in the garage to look at. so he strolled over and pulled back the canvas.

"A motorcycle out on the trunk road, snarling cocky as a fighter plane ..."

—Thomas Pynchon, Gravity’s Rainbow

And there it was. And he knew he was going to buy it. As soon as he saw it. Mrs. Korzanowski. a white-haired woman of about 60, came over as he stood staring at the machine and they both breathed in air disturbed for the first time in 12 years.

“That was Frank Jr.’s,” she said. “It’s been setting there, right like he left it since September 5, 1966. I remember the day.” She stared at it too, forgotten memories stirring after so many years. “I was always afraid he would kill himself on it.” She sighed. “But his father, Frank Sr.—he was just as foolish over motorbikes as his son was and the two of them together, they just had to get it.”

He saw a pair of worn leather riding gloves, the owner’s manual and a note pad covered with careful adolescent writing detailing steps taken to prepare the machine for storage. The odometer read 2323.4 miles.

“Frank Jr. was crazy about this bike, and I think his father was, too. Both of them were always fussing over it. They were going to race it after Frank Jr. got back from the service, Frank Jr. riding it, his father going to be the mechanic.”

The gas tank, a bright two-tone metallic red and white with a flashy star logo, looked showroom fresh. He could see how it would appeal to a teenager. The logo said “BSA.” He wondered who made BSA. “But then Frank Jr. didn’t come back—” His attention was arrested by Mrs. Korzanowski’s tone rather than the words.

A grief long since dead but still with power to cause pain. “I’m sorry. The war?”

“Yes. Over there in that country. Viet Nam. They were real nice, sent a man over from the army base. There was a real nice funeral and they gave us the flag.”

“I didn’t know ... I shouldn’t have looked at the motorcycle.”

“Oh, no. It’s all right.” She smiled at him, looking tired, older. “I wanted to sell everything. Frank Sr. passed away last month and, well, I can’t afford the house anymore. I’ll move in with my daughter.” She paused, her hands plucked at the tarp hem. “Frank Sr. wouldn't sell the motorbike. Wouldn’t touch it. Just always said, ‘Leave it be. It’s all right where Frankie left it,’ and he wouldn’t hear no more about it. And so it’s just sat here all these years. Nobody’s ever touched it. It’s practically new. You can see how good Frank Jr. kept it.”

“How' much do you want for it?” He wanted to bring her back to the present.

“Well, I don’t really know' how much it should be worth ... it is practically new. Maybe $1000.”

“I could go $750.”

“Well. . . .”

“Maybe $800.”

“I suppose that’s about all I could expect. . . .”

And so he had it. Mrs. Korzanowski insisted on giving him Frank Jr.’s tools for working on the machine, and the shop manual. “It’s no use without the motorbike.” He thanked her and felt foolish and somehow proud as he wheeled what he quickly saw was a very beautiful motorcycle down the street to his house. He parked it in the driveway and looked at it. Sitting still it seemed to prance. Sunlight glinted off the chrome, handbuffed just yesterday, it seemed, by the hand of a boy dead for 12 years. Somehow the bike seemed happy free of the tarpaulin.

He read Frank Jr.’s penciled notes about a teaspoon of oil in the cylinders and the battery stored in the freezer in the back pantry. He went back and got the battery.

It was still there. It was flat. He put it in the car and went downtown to find a bike shop. Honda. Honda. Kawasaki. Yamaha. Suzuki. No BSA. He finally looked in the phone book and drove back to one of the Honda shops. Yes, there was a faded Genuine BSA Parts sign tacked on the wall.

The young fellow behind the counter looked bored as he went over and hooked up the Lucas battery to a charger. “I can charge it but this thing isn’t gonna hold the charge.”

“Well, I’ll buy a new one.”

“We don’t stock them anymore.” “Anymore? This is a BSA dealership isn’t it?”

“Was. BSA went out of business three or four years ago.” Of course. He should have guessed. Bye-bye $800. The enthusiasm he had begun to feel for this new purchase started to evaporate.

Hearing the talk about BSA the mechanic, a man about his own age, came over, smiled at him, wiping greasy hands on the back of his overalls. “What kind of BSA you got?”

He dredged up the name in the owner’s manual. “A BSA Spitfire Mark II. 1966.” “A Spitfire! I haven’t seen one of those in here in years.” The mechanic looked past him. “You ride it in?”

“No. I just brought the battery in to be charged, but this gentleman tells me it won’t take the charge. I need a new one.” In minutes the mechanic had him fixed up with the appropriate Yuasa substitute and, treating him as a fellow conspirator, waxed eloquent on the virtues of British motorcycles, the unfair tragedy of their demise. Thus he found his newly acquired motorcycle had been made in Britain, had once been the best motorcycle in the world, had fallen on hard times with the rest of Britain and was fast disappearing into museums and junkyards.

On the sixth try the BSA came to life. The years of suspended animation were over.

“Bring her on down sometime. I’d like to see a Spitfire again. Great bike. Strong runner.”

Promising he would, he escaped. A motorcycle owner for less than an afternoon, suddenly he found he had dipped into an unknown world of passionate allegiances.

Before he tried to start the engine he read through the crisply new but yellowed service manual carefully and traced every control and part on the bike, peering and probing, pushing, pulling. He studied Frank Jr.’s notes, too, and followed his careful step-by-step instructions for bringing the BSA back to life. It was fun, and gave him something to do after work.

But the notes troubled him. The hand tracing the letters had been firm, unhurried, the mind directing it straight forward, thoughtful, as if it knew someone else would one day read the directions. The handwriting carried a remnant of the child, too, and, he felt, but couldn’t pin down why, it revealed a vaguely uneasy naivety. Had Frank Jr. sensed the doom 23 weeks in his future?

Always, however, his mind returned to the solid machine before him. The assertively colored gas tank was fiberglass (or “glassfibre,” as the manual put it) and held two gallons, which struck him as an awfully small amount in these days of looming gasoline shortages. The machine weighed 382 lb., which sounded heavy, but which he found out was light for a 650. The motor produced 55.5 horsepower, which seemed a great deal, but he learned it was not, anymore. The “ten-and-a-half-toone” pistons warned him the bike would be temperamental and might not like contemporary gasoline. It was and it didn’t.

A late spring frost lay lightly on the grass beside the garage the Saturday morning he finally decided there was no more to learn from the manual, no more prepping to do. It was time to start the thing and go for a ride. Ignition off, he pushed the engine over with the kickstarter. The oil was stiff and resisted. He had to use muscle. He depressed the “tickle” plungers on the carbs, waited for gas to flow out. None did. Then he remembered to open the fuel taps. Gasoline squirted out and over the carbs. And his hands. He wiped that off on his new blue jeans, switched on the ignition. The headlight nacelle-mounted ammeter jiggled. Foot probing with the kickstarter, he eased the pistons up toward compression. Then, throwing his weight onto his leg he jumped down on the starter lever.

Ka-paHhh.

Five more times he jumped on the starter. On the sixth try the BSA came to life. The years of suspended animation were over.

The bike snorted and bellowed as he worked the throttle, trying to keep the resurrected life from dying. Puffs of dust were startled into the air by the pulsing exhaust. Torque jiggled the bike sideways and forward on its centerstand. The hair on the nape of his neck rose. He had the biggest grin he'd had in 20 years. This was neat.

continued on page 142

That’s how his wife, aroused by the booming exhaust of the BSA. found him when she came out to the garage.

“What on earth are you doing?”

He grinned at her. working the throttle, his nostrils filled with pungent exhaust fumes. “It’s beautiful!” he shouted.

“What?”

“I said. “Want to go for a ride?’ ”

“A ride? On that thing?” She shook her head, wanting to come out with a disapproving frown. But she didn't. He looked too happy.

So he swung a leg over and found himself astride the BSA as it chugged and shuddered. He rowed it forward with his feet and it clanged off the centerstand. He hesitated an eyeblink, then pulled in the clutch, toed in first with his shoe, let the clutch out and he was jerked out of the garage, down the driveway and into the street, the BSA plunging away like an overeager race horse.

The bike wanted to go. Fifteen mph in first thrilled him as he rediscovered just how fast five times walking speed is. A clumsy shift into second and my God he was doing 40 and the bike still strained to go faster and the w ind was really cold and he really felt good and look at how the pavement blurs just under your feet and didn't the morning air taste good and. . . .

Thus he found out that motorcycling, while highly sensual, has nothing to do with misdirected sexual feelings, contradicting what he'd been told regularly in the Sunday supplements, and that nevertheless it was intensely pleasurable. His wife didn't know' that. One Saturday morning as he strode into the garage slipping on Frank Jr.’s riding gloves, he found her staring at the old-new Spitfire with something in her eye that hinted of jealousy at a rival. When she saw him she went back into the house without speaking. He looked after her. shrugged. He had to ride. The BSA wanted to run. She was being silly.

And he rode. The BSA took him along roads he had never been on before in his pre-programmed life. But always they seemed familiar. He thought often of Frank Jr., tried to imagine w hat it was like to be graduated from high school in June. 1966. know ing come September you'll be in the army, an army with a nasty war to fight, tried to imagine w hat it was like to get this thing you've yearned for and saved for all through high school, this BSA. to know you've got it for only this summer and that you've got to get all those dreamed of rides in now. Got to make good times to remember for the bad times, the uncertain times, to come.

The BSA was ignorant of the larger fate brooding over itself and its rider

Thus the expensive “English Make” riding gloves, the ground-oft' footpegs, the exhausts flattened on the bottom.

Aviation gasoline from the local airport solved the engine knock that gas station “Super” gave the affluent Sixties bike and he found he could fly down deserted morning roads with the speedometer needle well beyond 100. Hunched down over the gas tank, the pistons shotgunning into the head, the exhaust cannoning, he flew past a road repair crew at 115 mph. Stopmotioned by his speed, the men stared at him in open-mouthed surprise; the crew, their bright yellow truck, the sun on the tree line shooting brilliant scarlet beams and long black shadows, the shriek of the w ind keening between his ears and helmet, the chin strap tight, the bike and his body one living creature: all formed a brief connected picture which . . . Suddenly it flashed into his brain. He remembered. He remembered.

A few miles down the road he slowed, pulled off the highway, rode into a field and stopped. He remembered doing that before, racing past a morning road crew on the Beezer. But of course he Hadn’t. He got off the bike and looked at it. It was a machine. Bits of metal and rubber and fiberglass. But by God it remembered, too. He was sure of it.

He rode home slowly that day, but in succeeding days, on subsequent rides, the BSA kept taking him places he had never been but which he remembered—or thought he did. he told himself. Thought he did.

He lost 10 lb., quit smoking and kept riding. And kept remembering. Until it was September 5.

He felt a growing bond w ith Frank Jr. as the BSA took him higher along the twisting mountain road. He had never been on this road, never even knew it existed until today, yet he had memories of having ridden the BSA here before. He remembered landmarks, the occasional cabin. He remembered the road. Downshift here, bank now, but the line just so.

The crest, swinging from left to right across his vision as the bike ran after the road’s shifting spoor, grew ever nearer, closer. Was it some sort of déjà vu? Or had Frank Jr. been on this road before, too? Again he had the feeling of retracing the plot of a story 12 years gathering dust.

Suddenly the confident hammering of the Spitfire’s exhaust soared away as the wall of rock to his right dipped behind him and he topped the mountain. A crosswind planing up the side of the mountain and across the ridge line, which the road followed briefly before plunging down again, slapped him in the face and he sucked in the cool, pine-scented air. He sat up tall in the saddle, steered w ith his fingertips, taking in the vista of receding mountain peaks, flushed with the fast ride up the twisting road. More than once the soles of his boots had grazed the pavement.

He thought about stopping but the BSA seemed to want to go on. He rolled on the throttle and plunged off the crest down into the shadows of the eastern slope. The road was worse on this side, older, the edges eroded into rubble, repeatedly patched, painted markings long since faded. Off-camber, decreasing radius curves switchbacked down the flank of the mountain.

He should have slowed down, should have idled the bike along, enjoying the feel of the horizon beyond the trees closing in as he descended. But he didn't. He still had the vague sense that he knew this road, that Frank Jr. had known it. The BSA threw' itself into curves at just the right moment. He knew where to grab the brakes till the front Dunlop chirped, when to downshift and crank the bike over, just when to roll out. throttle coming on. He knew. And the BSA knew.

continued on page 144

continued from page 64

The mechanic at that bike shop said you only had to think a British bike around curves. This BSA seemed to be doing the thinking for both of them. Their speed increased until they flew down the mountain. everything but the road an unseen blur.

They came around a curve trailing footpeg rubber and there was a flash of sunlight snaked across the road. A spring seeped from the rock face and ran across the slanting pavement to disappear over the cliff opposite. His heart was in his throat the instant he saw it, too late to do anything. He was going down, damned fool that he was for running this fast. But he didn't. The BSA flashed through the water, only a brief twitch of the rear tire telling him the water had really been there.

His heart went from his throat straight to the BSA and he risked loosing a hand from the bars to pat the gas tank. “Good old BSA.” Then he was all concentration again, riding the whirlwind the road and the BSA made for him.

There it was. And he knew he was going to buy it. As soon as he saw it

A dozen curves later, straightening out of a double ess, up-shifting into third, the exhaust loud in his ear as it caromed oft'the wall of rock to his right, spied the pothole, a big. rough-edged granddaddy astride his line.

If there was one thing he knew the BSA would do w illingly, it was change its line in a curve. As soon as he saw the ugly shadow he nudged the bike over to cut inside it. But the BSA shook its head and drove straight on. He had time only to begin to wrench at the bars when there was a brutal shock and he was flying through the air and the BSA was cartwheeling over him. its chrome flashing in the sunlight.

He looked for the BSA. It was gone. Never get it out of there. Feeling shock coming on, he turned and walked down the road. Find help.

He hit the berm with his shoulder. A shock of pain flashed him momentarily unconscious as he rolled along the edge of the road and over the embankment, picking up gravel in his knees and elbows. He tried to get up before he stopped rolling, was slammed down, relaxed and let what would happen to him happen.

He did eventually stop rolling. He was on his feet in an instant, scrambling up the side of the embankment to the road. By the time he stood on the pavement he knew' his shoulder was broken.

He looked for the BSA. It was gone. Never get it out of there. Feeling shock coming on, he turned and walked down the road. Find help.

continued on page 166

continued from page 142

Around the next corner he stopped.

A tractor-trailer loaded with big redwood logs had jack-knifed and lay across the road, blocking both lanes and shoulders. A sheriffs ear was parked behind the rig. A knot of people stood nearby. If he had come charging around this curve there would have been nothing he could do. The huge logs jumbled across the road, the rig blocked every av enue of escape.

The shock of the accident just past and the clear vision of smashing head first into the truck at 60 miles an hour sucked the strength from his legs and he accordioned to the ground. The pain in his shoulder— he couldn't remember such pain, not in years—made him violently nauseous, but he was too weak to retch. He felt very old. And very foolish. At his age. to be playing road racer on a motorcycle ... He stared at the wrecked truck.

A sheriff's deputy walked up to him. looked him over with kindly concern. “Have an accident? We heard the cycle coming but there was no way to get up here and wave you down in time. Then we didn't hear you anymore.”

The deputy glanced up the road. “What happened?”

“Hit a pothole. Lost the bike.” He was feeling very weak.

“That pothole!” the deputy murmured, his mind half on the tractor-trailer accident. half beginning to realize he had another accident to deal with. “Yeah. I’ve bent a tie rod or two on it myself. The highway department keeps patching it and it keeps coming back. There’s a stream runs under the road there and it keeps undermining the pavement. Always been a pothole right there as long as I can remember.”

The deputy looked back down at the jack-knifed logging truck. “But you were might lucky you hit her. The way you were coming . . . you're damn lucky.”

“Yeah. That’s just what 1 was telling myself.” And he fainted.

He slipped in and out of conscious awareness as the deputy drove him down the mountain. The BSÁ knew that road, had been on it before, he was sure. With Frank Jr. The Beezer had carried him along that road at speed with an accomplished ease he knew he had not the skill to duplicate. But Frank Jr. could have. A 19vear-old bike freak on a motorcycle he knew intimately and loved as some people can truly love exceptional machines, a 19year-old who knew this was his last ride for years, maybe forever, could have ridden that way.

As he cradled his shoulder against the swaying of the police cruiser, the feeling grew that this road had been Frank Jr.'s last ride. The BSA had been retracing a pattern.

continued on page 171

continued from page 166

The BSA had always seemed to know where to go. only needed him to operate its eontrols. Right up to the last road and the pothole. And there it had turned from its accustomed character, its ease of control, of precise handling. The BSA had refused to change its line in a curve. It had smashed into that pothole, destroying itself. cruelly injuring its rider. The refusal saved his life. The rig was across the road: He would have died.

He stared at the trees outside the car window, listened to the static of radio chatter, the hiss of the tires on the pavement. How could the BSA ... a machine . . . know? Mayhe it was Frank Jr., then, riding with him. or some residual hond of affection, some part of himself the boy had left with the machine.

He should have slowed down, should have idled the bike along

Suppose Frank Jr. and the BSA. rushing locked in mutual rapture down that tortuous road confronted that self-same pothole. Suppose the BSA dodged it just as the Birmingham engineers had designed it to do. Assume the ride ended uneventfully (obviously it had) and Frank Jr. stored the hike away and went off to make his peace w ith the draft. . . and never returned. And the BSA. abandoned, knew. Somehow. And brooded in its mechanical heart, under the canvas and the yearly fall of dust, as the oil drained from its hearings, left them raw and drv. The BSA knew that contrary to the nature built in to it. it had betrayed its rider, the youth it had been made for. Had betrayed him by doing what it did best. In naïve pride at its ability the BSA had arrogantly side-stepped the yawning pothole and raced on. its rider safe.

But the BSA was ignorant of the larger fate brooding over itself and its rider, the oblivion of an untidy death 6000 miles away from home for Frank Jr., of years of black waiting for itself. And in those years the BSA. in its steel molecular resonances, reproached itself for not striking that pothole, not sacrificing itself to save its rider who, his induction delayed a few weeks, would have had a different fate, not been where the mortar shell fell, the bullet passed. Would have returned to ride the BSA again along the delicious w ind of the mountain.

And so the hike had waited. Waited until the chance came again, another rider came. Until there, the same road. There, the same pothole. But this time, with foreknowledge. there was a different ending to the ride and the BSA. the last lingering material expression of Frank Jf.’s spirit, released from its self-torment, flew out and over the road to disappear, returning to someplace where it is always 1966. 0