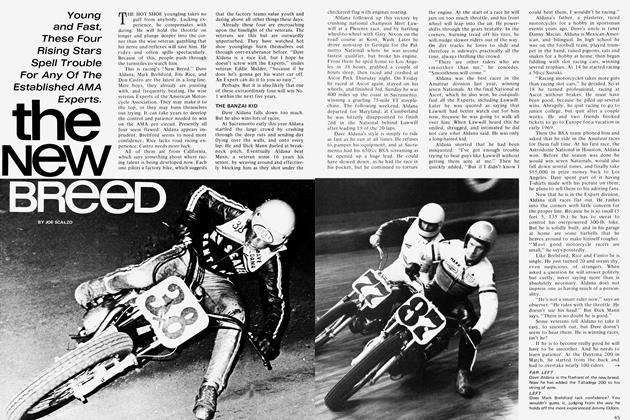

RESWEBER -THE GREATEST EVER?

"There Was No Fear In His Eyes, Only A Content, Almost Dreamy Expression . . ." 'By Keeping My Feet On The Pegs, 'He Explained, 'I Get A Better Feel. I Almost Become Part Of The Motorcycle.' "

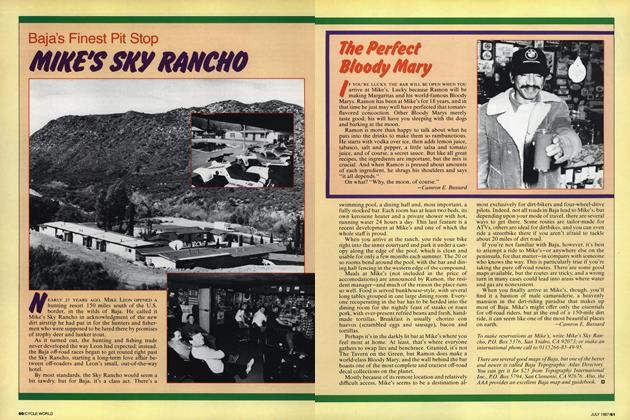

JOE SCALZO

SIX YEARS AGO, at Daytona Beach in 1964, I saw Carroll Resweber in the crowd. It was late at night. The 200-mile race was only three days away. Resweber was standing in the doorway of one of the small downtown garages, a smile spreading across his face as he observed the bedlam of the Yamaha team inside.

Mechanics, some speaking Japanese, others English, were darting around, often bumping into one another. Wrenches and engine pieces were scattered all over the garage floor; pools of oil were everywhere. One small mechanic, running with an engine in his hands, had his feet go out from under him in the oil and went down with a thump. Amidst all the noise and confusion, no one noticed Resweber in the doorway.

Then Neil Keen, one of Yamaha’s contract riders, spotted Resweber and rushed over to greet him. Other riders in the crowd immediately followed. Mechanics laid down their tools and came over to shake Resweber’s hand. Autograph seekers began shoving pieces of paper at him.

This was Resweber’s first appearance at any race since the accident that had nearly killed him at Lincoln, 111., two years before, and the reception he was getting must have been gratifying to him. He grinned, he shook hands, he signed autographs for a long time.

The next day the rumor swept through the Daytona pits and grandstands: Resweber was making a comeback! He would ride a giant 70-horse power Harley-Davidsdn, good for 150 mph on the straights. The factory had built it in top secret, just for him. With the great Resweber riding such a bike, no one else would have a chance.

But Friday and Saturday passed and Resweber did not show up. By now, everyone was looking for him.

Right up to the start of Sunday’s 200-miler I still expected Resweber to make a dramatic last-minute appearance. He would start in the back, but would overwhelm the riders in front of him with ease; riding in heavy traffic had always been one of his specialties. Finally the starter threw the flag, the race roared away. Resweber was nowhere to be seen.

There were reports afterwards that he had been seen standing in some of the corners, clocking the different riders. I did not see him in the corners, but late in the race, as I was drinking coffee in the infield cafeteria, I saw him sitting at a table with his wife. After a while he stood up and hobbled toward the door: a wiry, swivel-hipped figure who favored his right leg as he walked. He and his wife must have left town right afterwards because no one saw them at the awards ceremony that night.

Resweber did not come to another race all that year, or the year after that. By then most of his fans had accepted the obvious, grim as it was: that the injuries he had sustained at Lincoln on Sept. 16, 1962, had been too much, and that Carroll Resweber, who always rode the giant Harleys faster than anyone else, who won all the races, would never race a motorcycle again.

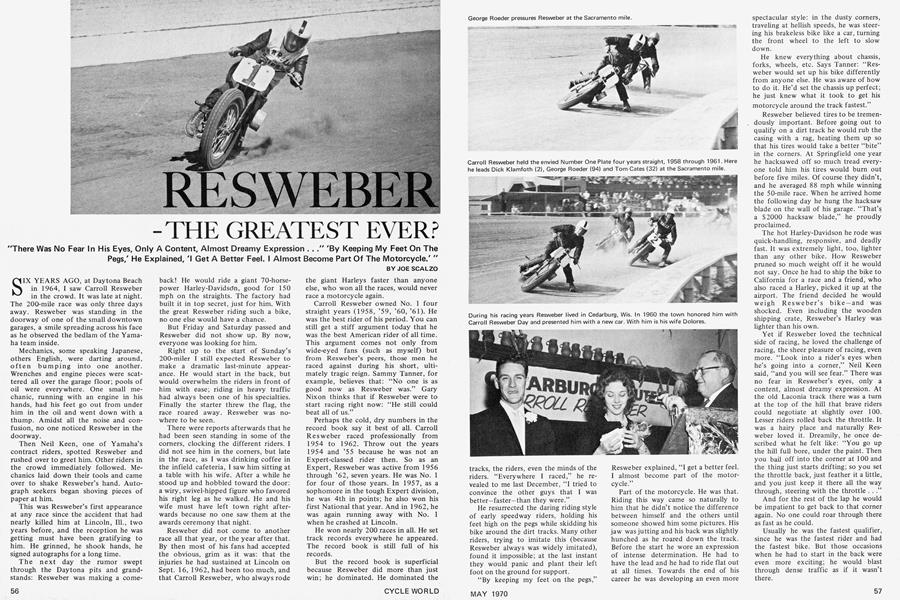

Carroll Resweber owned No. 1 four straight years (1958, ’59, ’60, ’61). He was the best rider of his period. You can still get a stiff argument today that he was the best American rider of all time. This argument comes not only from wide-eyed fans (such as myself) but from Resweber’s peers, those men he raced against during his short, ultimately tragic reign. Sammy Tanner, for example, believes that: “No one is as good now as Resweber was.” Gary Nixon thinks that if Resweber were to start racing right now: “He still could beat all of us.”

Perhaps the cold, dry numbers in the record book say it best of all. Carroll Resweber raced professionally from 1954 to 1962. Throw out the years 1954 and ’55 because he was not an Expert-classed rider then. So as an Expert, Resweber was active from 1956 through ’62, seven years. He was No. 1 for four of those years. In 1957, as a sophomore in the tough Expert division, he was 4th in points; he also won his first National that year. And in 1962, he was again running away with No. 1 when he crashed at Lincoln.

He won nearly 200 races in all. He set track records everywhere he appeared. The record book is still full of his records.

But the record book is superficial because Resweber did more than just win; he dominated. He dominated the tracks, the riders, even the minds of the riders. “Everywhere I raced,” he revealed to me last December, “I tried to convince the other guys that I was better-faster-than they were.”

He resurrected the daring riding style of early speedway riders, holding his feet high on the pegs while skidding his bike around the dirt tracks. Many other riders, trying to imitate this (because Resweber always was widely imitated), found it impossible; at the last instant they would panic and plant their left foot on the ground for support.

“By keeping my feet on the pegs,” Resweber explained, "I get a better feel. I almost become part of the motor cycle."

Part of the motorcycle. He was that. Riding this way came so naturally to him that he didn’t notice the difference between himself and the others until someone showed him some pictures. His jaw was jutting and his back was slightly hunched as he roared down the track. Before the start he wore an expression of intense determination. He had to have the lead and he had to ride flat out at all times. Towards the end of his career he was developing an even more spectacular style: in the dusty corners, traveling at hellish speeds, he was steer ing his brakeless bike like a car, turning the front wheel to the left to slow down.

He knew everything about chassis, forks, wheels, etc. Says Tanner: “Resweber would set up his bike differently from anyone else. He was aware of how to do it. He’d set the chassis up perfect; he just knew what it took to get his motorcycle around the track fastest.”

Resweber believed tires to be tremendously important. Before going out to qualify on a dirt track he would rub the casing with a rag, heating them up so that his tires would take a better “bite” in the corners. At Springfield one year he hacksawed off so much tread everyone told him his tires would burn out before five miles. Of course they didn’t, and he averaged 88 mph while winning the 50-mile race. When he arrived home the following day he hung the hacksaw blade on the wall of his garage. “That’s a $2000 hacksaw blade,” he proudly proclaimed.

The hot Harley-Davidson he rode was quick-handling, responsive, and deadly fast. It was extremely light, too, lighter than any other bike. How Resweber pruned so much weight off it he would not say. Once he had to ship the bike to California for a race and a friend, who also raced a Harley, picked it up at the airport. The friend decided he would weigh Resweber’s bike —and was shocked. Even including the wooden shipping crate, Resweber’s Harley was lighter than his own.

Yet if Resweber loved the technical side of racing, he loved the challenge of racing, the sheer pleasure of racing, even more. “Look into a rider’s eyes when he’s going into a corner,” Neil Keen said, “and you will see fear.” There was no fear in Resweber’s eyes, only a content, almost dreamy expression. At the old Laconia track there was a turn at the top of the hill that brave riders could negotiate at slightly over 100. Lesser riders rolled back the throttle. It was a hairy place and naturally Resweber loved it. Dreamily, he once described what he felt like: “You go up the hill full bore, under the paint. Then you bail off into the corner at 100 and the thing just starts drifting; so you set the throttle back, just feather it a little, and you just keep it there all the way through, steering with the throttle . . .”

And for the rest of the lap he would be impatient to get back to that corner again. No one could roar through there as fast as he could.

Usually he was the fastest qualifier, since he was the fastest rider and had the fastest bike. But those occasions when he had to start in the back were even more exciting; he would blast through dense traffic as if it wasn’t there.

Continued from page 57

He devoted himself to racing. Even in winter, when the race tracks closed down and all the riders went home, Resweber would hammer big bolts in his tires and go to the ice-track races in northern Wisconsin. He had no outside interests. Racing was all he did.

He kept to himself and never said much, not even in victory. After he had won a race he would be surrounded by his fans in the winner’s circle. A grin would spread across his face, a faraway look would creep into his eyes. No one could understand how he could be so totally calm. They did not know that he was already looking ahead to the next race, and planning how he would

When he did talk, it was in a heavy Texas accent that some northerners could barely understand. Resweber was a high school drop-out and lacked a polished vocabulary, and perhaps that was why he was so closemouthed.

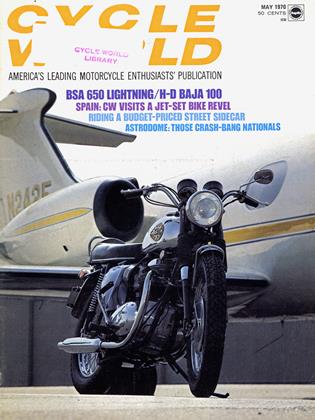

His fans always loved him. They voted him the “most popular” rider for two straight years. He accepted this honor quietly, shyly, as he did all the other honors that were heaped upon him. In 1960, the town of Cedarburg, Wis., where he lived when he was racing, held a Carroll Resweber Day, and gave him, among other things, a new car. Carroll slowly made his way to the podium. He fumbled for words, couldn't find any, and finally blurted into the microphone: "If I seem to be getting the best part of this deal, I hope you will understand." Then he hurried back to his seat as the audience ap Dlauded lona and loud.

Racing observers wanted to believe he was naturally gifted, which he probably was, although he never said so. He did believe that he had extraordinary eyesight and depth perfection. And he had a knack, or instinct, for racing. “I guess,” he conceded, “you have to have an instinct for motorcycle racing to be any good.” Then he quickly added: “But I just love to race, and I ride the way I feel the most comfortable.” Because he was so small (5 ft., 6 in., 138 lb.) he said he tried to “let the bike do most of the work.” Despite his small size, he was extremely strong.

Other riders thought him invincible and Resweber did everything he could to preserve such an image. Recently he told me why: “I had a lot of respect for all the guys I raced against, but I never let them know this. That was my edge. If I’d let them know that I was worried about them beating me it would have helped them. So I just kept things to myself.”

He let nothing break his concentration. Whether he was eating breakfast, going to bed at night or driving thousands of miles back and forth across the country to the different races, he would always be thinking up new ways to go fast. Even when he was on top, No. 1, he was dissatisfied. He was sure he had only scratched the surface. When Dolores, his wife, took out an insurance policy on his life he soon tore it up; he kept worrying about it and could no longer concentrate. Ironically, his crash at Lincoln occurred only four months afterward.

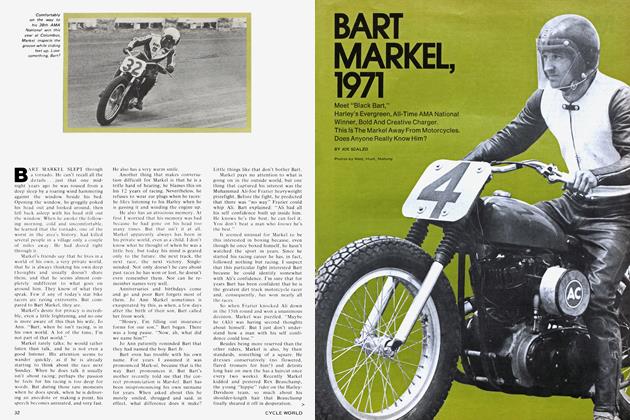

“Each guy has his one little bitty mistake,” Resweber says today, “and that’s what I worked on. You can’t pick up those things until you’re out on the race track. But if the guy ahead of you makes a mistake more than once he’s going to keep making it. That’s the theory I operated on, and it worked. Like Bart Markel. Bart Markel had as much stamina as anybody on the race track. Most of those other guys I could wear down. But with Bart there was no way. The only way I could beat Bart was to outsmart him.

“What it boils down to,” he concluded, “was that I did to them what I didn’t want them doing to me. I tried to bust their morale. I had to, because if I ever slacked off I knew I’d get beat.”

Yet at least one rider who played the psychology game with Resweber and won was Neil Keen. After beating Resweber at the 8-mile National race at Ascot Park in 1961, Keen informed Resweber that he had been seeing a psychiatrist. “It’s great,” Keen declared. “He’s convinced me that I can ride without fear.”

(Continued on page 86)

Continued from page 58

Resweber was impressed. “A psychiatrist,” he said thoughtfully, as if he might like to try it himself, “I never thought about that.”

Knowledge, natural skill, respect. Resweber possessed all three, and flaunted them. Yet the one thing he seemed to have more of than anyone else, which he was so careful to hide off the track, but which was so terribly obvious on the track, was his determination. He was determined to win.

Everett Brashear described Resweber’s determination this way: “He’s got so much determination he could be President if he wanted to.”

Resweber was always determined, even when he was a rookie. At Laconia he broke his collarbone in a street accident one night but raced the next day anyway. He ran off the track into some haybales, rebroke his collarbone and also fractured his big toe. Some spectators sat him back on his bike, gave him a push to get started again, and he rode on and on in terrible pain, finally finishing 1 3th.

At another early race he rode with a broken foot. He pumped it full of novocaine before the start to deaden the pain. The foot immediately went numb. Since it was the foot he shifted gears with, he spent much of the race shifting by hand.

There was also his determination in the early ’60s, when Bart Markel challenged him at every track on the circuit. Those were hairy races. And there was, in the end, his fierce determination to regain the use of his shattered left arm following the awful crash at Lincoln that changed his life.

He was born in 1936, in Port Arthur, Texas, where, through a freak of circumstances, he lives today. His father was a butcher, earning only $75 a week, and Carroll and his older brother and sister grew up lean and hungry. His brother raced midget-cars for a time. By the time Carroll was 12 he was bounding through the local oil fields on a 4-horsepower scooter. Later on he acquired a big, fast Harley. At age 14 he could skid around corners with his feet up on the pegs, do rubber-burning wheel-stands, and steer while sitting backwards in the seat.

Then one night he overshot a corner close to his home and plowed through a wooden fence, mashing his ribs. This did not slow him up at all.

Resweber told me: “When I’m doing something, that’s all I care about. If I can’t be the best at a certain thing I don’t want to do it. Maybe that’s a weakness, but I can’t help it.” So at 16 he quit school to race motorcycles. He began to pester every motorcycle dealer within 200 miles of his home for free parts—“Junk parts, anything you’re going to throw out. I can use them.” He nagged some of the dealers so much that they would chase him from their stores. One dealer angrily called him “a. mooch”; and “Mooch,” to the few people who knew him well, became his nickname.

He won 13 races in 1954, his first year on the tracks. He was very good. But he wanted to race against, and beat, the best and that meant leaving Texas and campaigning on the National circuit. One day in 1955, as Brashear, a Harley factory rider who lived in nearby Beaumont, was leaving for the circuit, he found Resweber sitting in his truck. “What do you think you’re doing?” demanded Brashear, who scarcely knew Resweber.

“You’ve got two bikes in the back of your truck,” Resweber informed him. “I’ll ride one.” And so they traveled on the National

so they on circuit together. At the Harley-Davidson factory in Milwaukee Brashear introduced Resweber to an engineer named Ralph Berndt. Berndt owned a KR Harley and agreed to let Carroll ride it. “That,” Resweber says now, “is when my career started.” He won 26 dirt track races that year.

He was 18 years old, a long way from Texas, and missed his 16-year-old wife. He sent for her and they settled in Cedarburg, a Milwaukee suburb. During the week, Resweber worked as a welder, making outboard motors for speedboats. On the weekends he would go out on the road, following the National circuit. Pretty Dolores Resweber stayed home, raising their two children.

In 1956, Resweber’s first as an expert-class rider, he won 26 races. They were only small races, and now he was hungry to win his first National.

This occurred the following year, 1957, at Columbus, Ohio. But Resweber did more than merely win the 10-mile National, he devoured the field. The great Joe Leonard, the No. 1 rider at the time, was a full straightaway behind him at the end. People rose from their seats to cheer him. By the end of the year Resweber had beaten Leonard at another National—the 5-mile at Minneapolis—and now was sure he could win No. 1 as well.

Taking No. 1 away from the veteran Leonard, however, was never easy. Like Resweber, Leonard was awesomely talented. At Springfield in 1958, he and Resweber dueled for miles. They were inches apart in the corners and as they plunged down the long straights they would look over and grin back and forth. One little mistake could decide the winner. In the end, it was Resweber who made it. He bumped into Leonard’s rear wheel at the finish line and lost to Joe by about six inches.

(Continued on page 90)

Continued from page 86

It was the last mistake he made in ’58. By the end of the season he was crowned No. 1, beating Leonard by a handful of points. The Resweber years in motorcycle racing had begun.

He was No. 1 in 1959 and ’60. He was getting faster every year. Berndt, his mechanic, a cool, methodical man whose temperament seemed to match Resweber’s, was building him faster, hotter engines all the time. Berndt ground his own cams (with a special cam-grinding machine he had built himself), he tinkered with the carburetor and cylinder heads and upped the horsepower to about 50—a sensational output in those days.

But merely winning races and owning No. 1 was not enough for Resweber. He loved having obstacles to overcome. In ’60, after he became the first rider to win No. 1 three consecutive years, the AMA’s Lin Kuchler predicted that “Resweber’s winning No. 1 three times may stand as long as Babe Ruth's home run hitting record."

The next season, 1961, Resweber responded by winning his fourth straight No. 1.

Another time, Resweber was chatting with Roger Reiman, who had just won the 200-mile Daytona road race. Reiman was amazed that Resweber could ride so fast on dirt. How did he do it? Resweber explained: “You can ride a motorcycle around a half-mile track without ever shutting the throttle off. I’ve done it. But you don’t go fast that way. The only way to go fast on the half mile is to get in, get set, and get out of the corner fast. The guy that gets into the corner the hardest won’t necessarily win. It’s the getting out, the keeping your momentum going that counts.”

Reiman thanked him for this tip. And if Resweber ever needed any tips on how to road race, he, Reiman, would be glad to provide them.

Reiman didn’t mean it that way, but Resweber took this as an insult. He made up his mind to whip Reiman at road racing. At Shreveport, La., he showed up with a set of long, long handlebars bolted on his Harley. Reiman laughed at them: to control a bike on a road course, you needed short bars. Whereupon Resweber went out and won easily. “Those long bars may look funny," he said afterwards, "but I can get all my weight over the back wheel and it really helps me get stopped."

Things like this made the racing enjoyable to the young Resweber. The Harley factory always treated him like a prince, paying his expenses (at Phoenix in July, 1960, for example, they flew him in a week before the National so he could become accustomed to the scorching 110-degree heat) and offered to set him up in a dealership of his own. All he wanted to do was race, so he said no. The most he ever made in purses for a single year was $17,000, not much considering how good he was. He was too intelligent not to realize this, and it troubled him. Even when he was No. 1 he still had to hold down his welding job to support his family. Therefore, by 1961 he was thinking seriously about quitting motorcycles and going into auto racing, as Joe Leonard had before him. He’d had offers from big factory teams; auto racing was anxious to get hold of him, and would pay him well.

Also, the pressure of holding No. 1 for four straight years may have been getting to him: “If you go to a race and win, people say, ‘Well, he’s supposed to win.’ But if you lose, they come up to you and ask what happened—as if you have to have an excuse.”

A few days before the season started he broke the news to Dolores. He was getting out; 1962 would be his last year on the tracks. He told no one else, not even his arch rival, Bart Markel.

(Continued on page 92)

Continued from page 90

“Bart and I never said too much, and we never joked about the racing,” Resweber says today. “We raced hard, and sometimes he’d shut the gate on me and sometimes I’d do it to him. We both knew just how much we could pull with each other. One time I bumped him—it was an accident—and afterwards he found me in the pits and said, ‘Well, that’s one I owe you.’

“But I believe that Bart, in his own mind, felt he could beat me. I knew how much he wanted to win. But I couldn’t look at it that way. I had to figure that any time he beat me he was just taking money out of my pocket.”

Resweber and Markel battled all summer. Both rode factory Harleys. Both appeared to be evenly matched. Neither would surrender. Resweber kept probing for an edge, trying to find a way to put the ferociously competitive Markel on the defensive.

Finally, at a small non-National dirt track, he found a way: “In one of the heat races Bart and I just dueled like fools, pitching it into the corners at over 100 and sliding all the way around only about a foot apart. I was completely worn out afterwards and so was Bart. We’d been racing way over our heads.

“I’d made up my mind that I wasn’t going to ride that hard again in the main event. It was just too risky. I wasn’t going to stick my neck out that far. So I started thinking what I could do to brainwash Bart, and finally it came to me. Just before the start of the main I called to him, ‘Hey, Bart, wasn’t that heat race a blast? That was fun.’

“Well, the look on his face told me I’d done it. He was shocked. Now I had an edge on him. And I used it to beat him.”

Resweber won that race, and he won the National at Watkins Glen shortly afterwards. Now the circuit went to the 5-mile National at Lincoln. About all Resweber had to do was finish at Lincoln, and he would repeat as No. 1. Then he could retire in glory and start a brilliant new career in cars.

Few people doubted that he would win. And of course no one thought about the possibility of Resweber crashing. He was too skilled a rider.

But while Resweber rarely crashed in the big races, he had in fact crashed several times at smaller races. The crashes had usually occurred toward the end of the season, and he had been able to hush them up. Frequently he rode while injured, too proud to admit he was hurt. Going into Lincoln there were few bones in his body that had not been broken at least once. “But I never figured I’d get hurt bad,” he says now. “I always figured it was the other guy who would be hurt bad.”

This time he was hurt bad. His neck was broken. So was his right leg—in six places. It was in a cast for two years. The nerves in his left arm were so chopped up it was 18 months before he could flex his fingers and nearly three years before he fully regained the use of the arm. He was unconscious for nine days and recognized no one, not even Dolores, for a month.

The track was rutted and very dusty. He was out practicing (he believes he was out practicing, since to this day he recalls nothing of the accident). Ahead of him riders Jack Goulsen, Dick Klamfoth, and J.C. Robertson smashed into each other and went down right in the middle of the track. A great cloud of dust mushroomed up.

At 100 mph Resweber streaked straight into the dust and momentarily disappeared. In the past his quick reflexes had gotten him out of dangerous situations. At Dodge City one year his bike had hit a puddle of oil, skidded, and tried to throw him. But he held the handlebars in a deathgrip and saved it.

At Lincoln in the dust he never had a chance. He crashed into the wreckage with terrible impact. Those in the grandstands later reported seeing three pieces come pinwheeling out of the dust. Two of them were Resweber’s lightweight Harley, which had been torn in half. The third piece was Resweber, who was hurled into, then through, the infield fence.

Goulsen died in the ambulance; Resweber nearly died. A fast-thinking attendent gave him mouth-to-mouth resuscitation enroute to the hospital and saved his life.

The recuperation period that followed was the worst time of his life. Not just the pain; he was used to pain. But as he lay in the hospital the bills piled up. The insurance money from the AMA was devoured quickly; the $1700 that Harley-Davidson dealers throughout the country raised for him went just as fast. His nine years of race winnings were swallowed up. Dolores Resweber took two jobs, working day and night to try to pay off the bills, which finally totaled $ 10,000.

The doctors had already told Resweber that his racing career was finished; now they told him he probably would never regain the use of his mangled left arm. The Mayo Clinic and Baylor University, after studying the x-rays, concurred.

Resweber angrily rejected their findings. After he was discharged from the hospital he built his own whirlpool bath, and exercised his arm day after day. Incredibly, the arm began to respond to this treatment. Today Resweber rates it "about 95 percent of what it used to be."

Markel had gone on to win the ill-fated Lincoln race, and now was No. 1. But everyone knew that the great Resweber would soon make a comeback. Oh, it might take him a couple of years to heal, but he would be back. Those who visited in the hospital, though, and saw how battered he was, were not sure. The accident had taken a lot out of him. He had decided to settle in his old Texas hometown of Port Arthur and the day he left the hospital, he shook hands with his doctor. “This racing,” he said ruefully, “has made an old, broken man out of me.” He was 26.

In Port Arthur today, Carroll Resweber lives in near-total obscurity. Few of Port Arthur’s 50,000 inhabitants know about his once-glorious career, or that he raced motorcycles at all. Most of them work in the nearby oil fields or at the docks (the Gulf of Mexico is very close). Just as in the old days, Resweber works as a welder. He is employed at the Marine & Industrial Machine Works, making about $ 1 0,000 a year.

He is 33 years old now, but maintains his old fighting weight, 138 pounds. He still is closemouthed. One of the few persons he communicates with from his racing days is Ralph Berndt.

His family is growing up; his daughter is 12, his son 10. Dolores Resweber, as pretty as ever, is happy that she has Carroll at home now after all his years on the road. In his spare time he buys wrecked cars, rebuilds them, then sells them at a fat profit. Occasionally he races early-model stock cars at the local dirt track, but not seriously, only as a hobby.

The den of his home is stuffed with his old trophies. Stored up in the attic are his leathers, boots, and a tattered old scrapbook.

They are all that he has left. Bitter? No, he isn’t bitter. However, there was undeniable sadness in his voice when I visited him in Port Arthur last December and he told me: “When the accident happened it was like cutting off one of my arms. I had No. 1 for so long, and to lose it that way. . . well, it was like taking part of my life away.”

His broken bones have mended. He is fit. He could resume racing motorcycles if he really wanted to. Apparently he doesn’t want to.

The past is the past. He can’t bring it back. He is satisfied and generally happy with his new, quiet life away from the tracks and the noise.

But sometimes the still nights in this little town can be very hard on him. Particularly those nights when he dreams about the corner on top of the hill at Laconia, and what it was like to roar through it at 100, the rest oí the pack far behind him. [Ö]