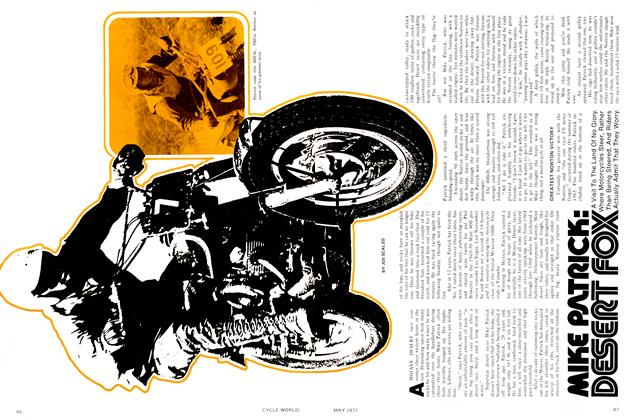

SHORT TRACK AS MICKEY MOUSE

As Competition, It Had All The Heroic Aspects Of A Slot Car Race. But If Mickey Mouse Is What It Takes To Fill Madison Square Garden, Maybe Disney Was Right.

WE SCREECHED to a halt in front of a horrible old fleabagger. It had to be my hotel, and of course it was. Well, the Hotel New Yorker might be old and crummy, but right now it contained the fastest motorcycle racers in the country. Tomorrow night, Monday night, they would be roaring around inside Madison Square Garden, just dowm the block.

I climbed out of the car. It was still snowing. The gypsy cabbie heaved my luggage onto the pavement and held out his hand: “Eight bucks.”

“You said seven back at the airport.” “Was seven, now it’s eight. That was a tough drive through the snow.”

JOE SCALZO

You can say that again, I thought, then paid him off.

I really must have looked like a mark. My first trip to New York and already this swinish city of striking cops and garbage men was one-up on me.

1 wasn’t angry, I was laughing. Some city.

I checked in, ditched my luggage in the dank room that had been reserved for me, noted the cheerful sign on the back of the door (“For your own protection lock your door at all times”) then took the elevator back to the lobby to try and find Don Brymer.

Brymer was sitting in the bar. He was dressed in a blue coat, red pants, boots

and wore a flashy scarf around his neck. Fancy dressers, race promoters. But then Don Brymer is not just any old race promoter; he had succeeded in getting a motorcycle race booked into New York, inside Madison Square Garden, something no promoter anywhere had been able to do since before World War II.

Somehow I had expected to find Brymer nervously peeping out some window, watching the snow piling up in the streets, worried sick that the unexpected storm would hurt his gate. Most promoters sweat blood about the weather. Not Brymer.

“The Garden is nearly completely

sold out for tomorrow night,” he told me jubilantly. “All 17,250 seats, and most of them sold in advance.”

I had to sit down. It was unbelievable.

Brymer was serious. He had been in New York for a week he said, bringing with him Mark Brelsford, the greatest indoor bike racer in the country. He and Brelsford had hit the newspapers and radio stations, trying to tub-thump the Madison Square Garden race, but they didn’t seem to be getting anywhere. So Brymer left Brelsford at the hotel and instead went back to the newspapers with a girl rider from California named Sammie Dunn. A cute one. The press

were five times as interested in Sammie as they were in Brelsford, even though Sammie wasn’t entered in the races. The publicity had been amazing. New Yorkers apparently could not believe that out in the wild West we let girls ride motorcycles.

Brymer said he had spent lots of money on advertising. (This I believed. The race was to be called the Yamaha Silver Cup, and it was rumored that Yamaha underwrote all Brymer’s expenses.) He sounded enthusiastic about all this. 1 couldn’t bring myself to tell him that 1 loathe indoor bike racing. Indoor racing, as I remembered it from watching a Brymer-promoted indoor meet in Long Beach, Calif, the month before, is all crashing and no style.

It's racing out of an amusement park, but with motorcycles instead of “dodge ’em” cars. The bikes thunder around a narrow, tight oval: they’re not supposed to run into each other but they can’t

help it. Brymer’s indoor track at the Garden was only a tenth-of-a-mile per lap.

Rarely is there enough room to out maneuver another rider and make a “clean” pass. To overtake a rider you bore into him, bash him in the kidneys with your handlebars, and if that doesn’t work, you ram him with your front wheel and shove him aside. A destruction derby. In a crude way, it’s exciting. But the ramming and gouging continues all night long and by the end, the various riders have wheel marks and rubber burns all over themselves and their bikes.

Afterwards you’d think they’d all go punch each other out in the infield. Surprising, no one ever seems to lose his temper when bumped.

Seemingly little skill is involved in all this, certainly not the skill you marvel at on a mile track or at Daytona. This is more like a circus sideshow. And the small size of the Madison Square Garden track would not be conducive to a feeling of speed: no one would exceed 50 mph, if that. But perhaps it does

take skill to know how to knock down the rider in front of you.

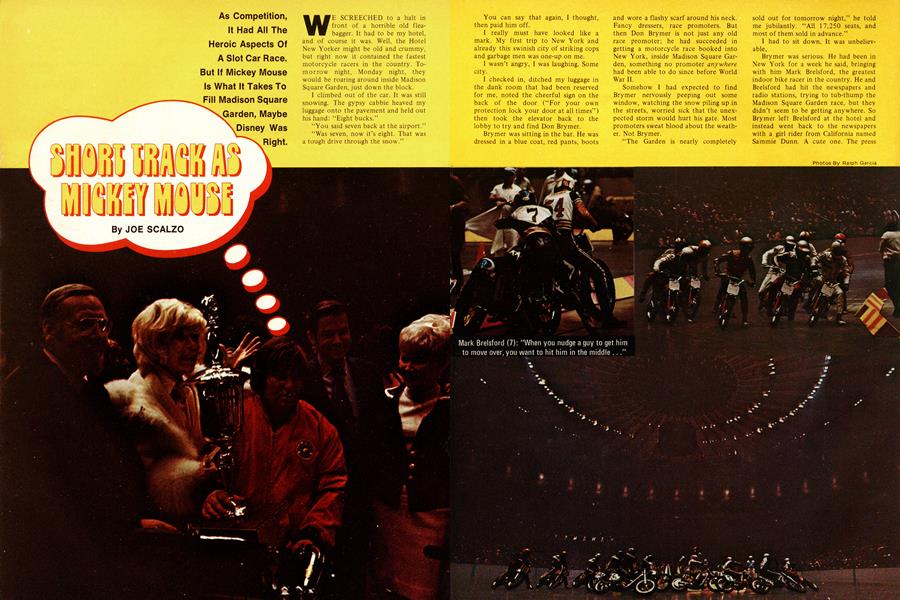

Mark Brelsford once explained, unashamed: “When you nudge a guy to move over, you want to hit him in the middle of the bike, or better yet, in the front tire. His bike follows the front tire and the bike will fall.”

A wild, weird, ridiculous kind of racing—ridiculous because you hate to see the best riders in the country out there running into each other.

The American Motorcycle Association has such a low regard for indoor racing (The Astrodome, of course, is indoors, but is also a dirt track and isa quarter-mile long) that they won’t award National points at indoor meets. Good for them.

Yet Brymer was saying he had a sell-out crowd for tomorrow night . . .

I’d asked the hotel clerk to ring my room at 7:30 so I could get over to the Garden early in the morning and watch practice begin. The snow had stopped and had given way to a dirty rain. The desk man warned me it was 31 degrees

(Continued on page 112)

Continued from page 68

outside, but I jauntily walked out the door any way—dressed, stupidly, in lightweight, California-style clothes. The block-long walk to the Garden nearly froze me. That, plus the now-usual fear of getting mugged on the sidewalks or being run down in the streets by the maniac cabbies.

I picked up my credentials at the Garden’s press gate, rode an elevator to the fifth floor, walked down a narrow corridor to the grandstands and was immediately overwhelmed by the wailing of two-stroke engines. Bui they were muted. Garden rules said all racing bikes had to wear mufflers a good idea. Brymer seemed to have thought of everything.

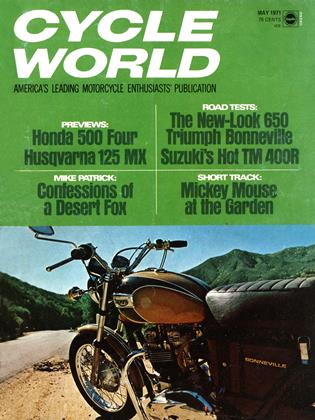

The so-called track, I noticed, was just as small as the one at Long Beach. It was set on the outside of what normally is an ice-hockey rink. The teardrop shape, 1 decided, would encourage lots of passing. And crashing. The surface was cold, gray concrete.

In the pits the riders were just beginning to arrive. The Californians far outnumbered everyone else, as usual. They were as bowled over by New York as 1 was. We exchanged horror stories about the city. That morning two of them had nearly been picked up by a couple of transvestites while walking to the Garden from the hotel.

There weren’t many big names entered. Breisford, Dave Aldana, Chuck and Larry Palmgren, Keith Mashburn, Jim Odom, and a chunky rider from Northern California named AÍ Kenyon were the big guns. Barry Briggs, the former English speedway star was here, which was silly, since indoor racing is not his bag. Gary Nixon showed up, more because New York is only a three-hour drive from Baltimore than from any deep-rooted love of indoor racing. Nixon told me that Ronnie Rail, a fine indoor racer, had been set to come but had broken his hand while cowtrailing in Ohio the week before.

Missing was the new No. 1, Gene Romero. Also Jim Rice, Dave Castro, Dick Mann, Mert Lawwill, Cal Rayborn, etc. Supposedly the reason was because Brymer wasn’t paying any appearance money; but 1 think it was because none of them like indoor racing enough to drive clear to New York.

Practice began. Right away it became clear Brymer was going to have a smashing show. Literally. The hard cement floor offered all the traction ot glass. It was claimed that traction would improve as the skidding bikes laid down a coat of rLibber, but none of the riders seemed sure ot this. Aldana, for one, dumped his BSA on the first lap of

practice, something he was to do frequently as the day wore on.

Nothing surprising about this; Aldana fell a total of 17 times at Long Beach.

That is the wierd thing about indoor racing. For all the wild spills, there are few injuries. Either the racing really is safe despite all the crashing, or an overdue bill is going to be submitted one of these days.

The practice laps proved nothing, except that any one of the 130-odd riders had a chance to win. Indoor racing is one of the few forms of AMA competition where Novices. Junior riders and Experts all run together. Anything can happen. Brelsford had already told me how easy it was to knock someone down if necessary. Since indoor racing is so hairy, and no rider was going to be penalized for rough riding, as would happen in other types of racing, the riders with the best chance, I decided, were the big brawny guys like Odom or Bob Bailey. Bailey, 6 feet 4 and 200 lb., was. riding a huge, heavy Honda.

“Between us, the bike and 1 outweigh everyone else by 100 lb.,“ Bailey boasted. “So it takes one hell of a nudge to move us out of the way.“ Bailey underestimated the other riders. By the time they were through with him he had been decked three times.

Practice continued. Muffled or not, that many motorcycles in a closed arena make a damn lot of noise. Tiie smoke and exhaust fumes raised, collected around the track lights high above the hockey rink. Every lap of practice seemed to produce at least one good spill. A rider would go down, would bring down several other riders with him, and they all would leap to their feet bang their handlebars straight, jump on again and continue. In the pits, mechanics were attacking tires with rasps. Some were spraying an acrid smelling goo onto the tires, believing it would improve traction.

Gary Nixon coasted into the pits during practice white-faced; he had narrowly missed two riders who’d fallen in front of him. I asked him what he thought of the obnoxious manners of his rivals.

“It’s safer inside here than out in the streets of New York,” he declared. I considered. He was probably right!

Besides, there was another consideration. A purse of $12,000 had been posted for all this foolishness, a lot of money, and Nixon had already computed that if he won his heat race, the trophy dash, and the main event, he could go home with $3500. For that much money he could afford to risk his notoriously fragile bones out on the cement floor-even though the first National of the year, the Astrodome, was set for the following Saturday.

I watched poor Aldana take another

pratfall. “The secret of indoor racing,” he said calmly, “is to be very smooth, and not get carried away.” Then he tore onto the track again and spilled again. There is only one Aldana.

The noise continued. So did the pileups and near-misses. It was a bloody madhouse.

Time trials finally got underway to determine starting positions. Keith Mashburn, riding a Yamaha for Yamaha, was the fastest qualifier with a well ridden lap o f 8. 61 s e c. A1 d a n a s h o c k e d everyone. He spilled (again) on his first qualifying lap; on his second lap he rode so carefully he knew he would be the slowest qualifier. Instead he was fourth quickest !

This shock was quickly followed by another much larger one; the size of the crowd.

I still couldn't believe that Brymer had really sold the place out, and I don’t think anyone else really believed it either. His Long Beach race had been less than a moneymaker. But this was New York, not Long Beach. An hour before the start 1 glanced up at the grandstands to see if anyone was there and discovered a howling mob, thousands of people spilling out into the aisles and hanging over the railings. There wasn’t one empty seat.

Incredible . . . and already Nixon and some of the shrewder heads among the riders were starting to wonder if they

were really getting a fair share of the purse after all.

How many of these people were motorcycle fans is impossible to say. This wasn’t really motorcycle racing anyway. But they were a New York crowd, and they were loud. They loved the show.

Brymer, meanwhile, was walking around beaming as if he had just found the key to Fort Knox.

The racing, the crashes, started early and it was impossible to separate the two and tell whether the crowd was cheering the racing or the crashing. One went with the other. Barry Briggs fell three times in the same heat race. Each time he fell he occasioned a complete restart since he and his bike had the track blocked. Briggs fell a fourth time on the final lap while riding too hard, and didn’t earn a starting berth in the main event.

The crowd gave him a roaring ovation and Briggs acknowledged this with a wave, trying to conceal the sheepish expression on his face.

But that’s concrete for you. Practically the only important thing is the start. Riders drop clutches and roar toward the tight first turn. With that many riders, it’s like trying to ride through the eye of a beer can. Usually one rider falls and brings down more

(Continued on page 114)

Continued from page 113

did not have to be restarted at least once.

Since the start is so important, each rider is inclined to cheat a bit. If he gets the jump on the others, he may make it around the first turn on two wheels.

Obviously the starter of the races had a thankless job. If he caught a rider jumping the flag he was obliged to send him to the rear of the pack. Unfortunately this starter went about his job with a little too much zest. If was as if he was engaging in psychological warfare with the riders; he was not going to let them cheat the start by so much as an inch. He sent rider after rider to the back.

To the crowd, the starter was a gimlet-eyed dictator. They hated him. They booed and hooted every time he moved a rider to the rear. The booing got so intense at times that I expected bottles and paper cups to begin raining down on him from the balconies, but they never did.

The mind boggles at what Eddie Mulder, the starter-baiting Southern Californian, would have done to this starter. Finicky starters like this are Mulder’s favorite targets . . . yes, it’s fortunate Mulder did not come to the Garden.

Moving the cheaters to the rear only made a bad situation worse. It allowed the cheater to get a rolling start on the field, brom the rear he would barge into the backs of those ahead of him so violently that bikes and bodies would go all over the track. Naturally, this caused a restart.

One who triggered mayhem three times from the back row was rider Dave Hanson. By the third restart all the riders lined up ahead of Hanson knew what to expect, so they left a narrow alley for him on the inside which he took and won the race. Hanson was the cue hall, the others were the number balls.

The program of heat races progressed. It wasn’t very skillful, but it was exciting.

I kept asking myself what are riders like Nixon, Breisford and Aldana doing out there?

Nixon was not upset when he didn’t earn a starting place in the main event: “Well, this racing is fair in a way. The strongest guys here, the toughest, the ones who stay on their wheels, are the only ones who are left racing at the end.”

Jimmy Odom seemed to be the favorite to win the 20-lap main now, which would take about three minutes to complete. Broadshouldered and strong, Odom also is one of the smartest indoor racers. Earlier, Odom had de-

feated the rough-riding Hanson in a heal race. He had allowed Hanson to jump him at the start, then let Hanson bash and plow his way through the traffic. Odom bided his time behind him. Leaving all the rough stuff to Hanson, Odom then easily blew him off once they cleared traffic. It was neatly done, the best piece of riding of the night.

Just before the main event came a “clown” race. It wasn't billed that way on the program, but that’s exactly what it was. Yamaha rolled out a bunch of little Enduro models and the likes of Nixon, Odom. Brelsford. Aldana and the Palmgren brothers dutifully boarded them for a bit of merchandising. On cue, they clowned their way through the 1 O-lap “race.”

They bumped into each other. They did wheelstands. They ran over each other's feet. They held out their left hands to signal when going round the oval turns. The crowd laughed itself silly at their antics.

I felt a trifle hysterical. What were Aldana and the others going to be asked to do next, jump through hoops? Wear clown suits? Put greasepaint on their faces?

Only in New York. Or Long Beach.

After the clown race, the main event was anticlimactic. AÍ Kenyon won, leading all the way after Odom and Aldana bounced off each other in the first turn.

There were only two spills, so it was pretty dull. Aldana fell for the eighth or ninth time. Toward the end the wildriding Hanson slammed into Mark Brelsford from behind, breaking both bikes, tearing the back out of Brelsford’s leathers and leaving him with some very sore ribs.

Riding a Bultaco, Kenyon had won the Yamaha trophy. Five more Bultacos followed him across the line.

Earlier, actress Carol (’banning, the “trophy girl,” had been ridden into the Garden by motorcycle sidecar. A high school band from the Bronx paraded in front of her. She congratulated Kenyon, who looked embarrassed about the whole thing. Carol, 48, was old enough to be 20-year-old Kenyon’s mother. But she didn’t look like mother.

It was eleven o’clock and the long, slightly unbelievable evening was finally over. The crowd started spilling out of the joint in a wild surge. I expected people to be trampled, punched, attacked. But it was an orderly crowd; there was no violence.

1 saw Don Brymer standing in the middle of the infield, watching the crowd depart. Exhaust smoke was still in the air.

“What did you think of the show?” he boomed at me.

Not really knowing what else to say, l replied, “Well, it really went over didn’t it?”

Brymer replied: “You bet it did. I’m

meeting with the Garden people in the morning about setting up more dates.” More indoor races. Well. okay. Apparently the AMA doesn't mind. After all, everyone went home from Madison Square Garden happy. The crowd obviously loved the show. Yamaha will probably sell a lot of Enduros on the strength of the clown race. Brymer made a lot of money. AÍ Kenyon earned

S2700 for three minutes’ work. No riders got hurt . . . which, to me, still is the most unbelievable thing of all.

Odom, who finished second, said. “I pushed Kenyon hard. 1 ran into him a couple of times like you’re supposed to do but he wouldn't move over.” He paused and looked apologetic. “I really don’t like to run into guys like that. But you have to here.” [Ö]