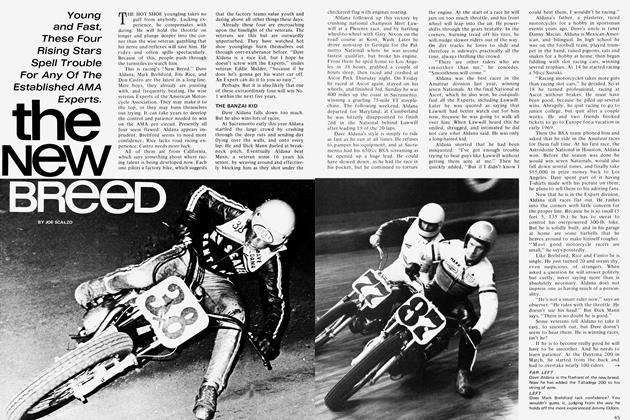

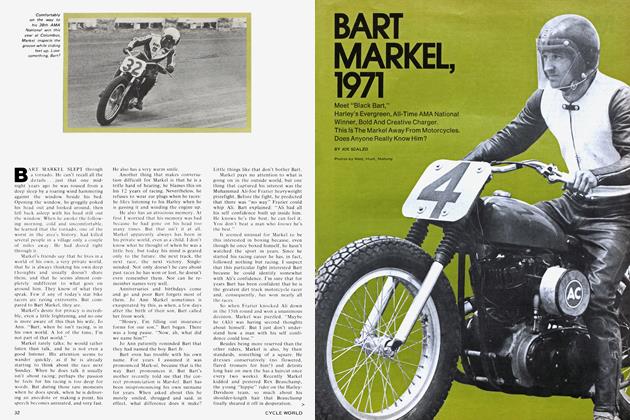

NO KIDDIN' AROUND

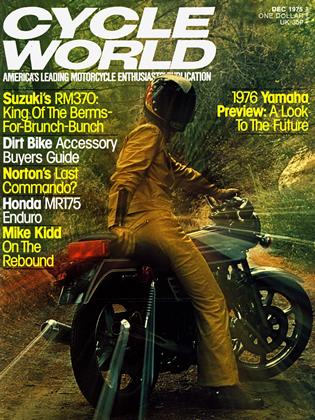

AMA Professional Mike Kidd Makes A Splashy Return To Racing After A Year's Absence.

Joe Scalzo

For much of last winter, Mike Kidd, the motorcycle racer, worried about Erica Kane Martin. The spoiled and self-centered heroine of the daytime TV soap opera All My Children was about to engage in mischief again, Kidd knew she was, and five days a week for 10 weeks, Kidd raptly watched her from the imprisonment of his plaster body cast. Occasionally he'd turn from the television set to his wife Sandra, and inquire anxiously, "Honey, what do you think Erica is up to now?"

The attempt to lose himself in TV fantasy while convalescing from his August 9, 1974, crash at the Santa Fe Speedway worked fairly well. Much better, for example, than pain-numbing drugs. Sometimes Mike needed sedatives, though. His arms, at least, were free for reading. Unfortunately, Kidd's reading material consisted entirely of motorcycle-racing publications, and when he read about the racing of others, it depressed him. So the TV soaps were best. The shredded bone ends knitted slowly, and Mike Kidd sat very still ("My doctor tole me to lay real still. The quieter I was, the quicker I'd heal.") watching Erica Kane Martin and attempting to enjoy his new house.

The house. Located right there in little Richland Hill, Texas, on the highway between Dallas and Ft. Worth. Kidd had moved in that July. At the time he was 4th-ranked professional motorcycle racer in the U.S. Two weeks later, before much of the furniture had even been uncrated, Kidd smashed into a wall racing at Santa Fe Speedway in Chicago, Illinois.

The wall that Kidd's body struck was supposed to be cushioned by haybales but wasn't, and from the first flash of pain that went through him, Kidd thought he'd fractured his back. He hadn't, but one leg was a mass of torn and bleeding flesh. Three bones were broken just above the left knee. As the ambulance bearing Kidd off the track passed close to where I was standing in the Santa Fe infield, I could see through the ambulance windows that Mike was waving his arms. I took this to be the little Texan's way of assuring everyone that he was okay; it seemed like the nice, considerate sort of thing that only Mike Kidd would do. Actually, he was waving his arms in desperate pain, pleading for a pain-killing shot, but none of the track orderlies had the authority to give him one. Nobody in the ambulance could do anything until they reached the hospital, not even Sandra Kidd, 16, who sat silently clenching her husband's hand, and blinking back tears.

"All the time in that dang ambulance I kept trying to pass out, so the hurt would go away," Kidd told me a few days later. He was propped up in bed at the austere and cheerless hospital a few miles from the track. He looked awful. His face was very pale, and somehow the big hospital bed made him appear smaller than he actually is. Braces and wires supported his mangled left leg.

"I kept a-tryin' to roll my eyes back," he continued, "to make myself pass out, but I couldn't do it. I guess I was screaming and hollering a little bit too. . . .

"We got to the hospital at 15 minutes to 11, but there wasn't no doctor on duty; nobody was there, and it was a long time before I finally got my pain shot.

"By one o'clock they got around to taking X-rays on my leg. It was a pretty weird break. I'd broke the femur, the big bone, but actually there were three different bones all kind of laying around up there. They kind of wiggled them around before X-raying. It definitely hurt.

"I wanted another pain shot, but the doctor said no. Then he drilled a hole into my leg just below the knee, and stuffed a pin in there to hold my bones in traction. Whew, he did that without putting me to sleep even."

Then Kidd gestured for me to come closer and whispered urgently: "I sure want to get out of this place, get sent home. I can't stand it here. You can't eat this hospital food. And the doctor I've got hates motorcycles. Hates 'em. Every time he sees me, the first thing he says is, 'You're crazy to race motorcycles.' Well, someday I'd like to remind him that it's my motorcycle racing what's gonna pay his bill."

Across the room, Sandra Kiddshort, brunette and doll-like—sat listening to her husband, hanging on his every word. It was August 21st. It was the Kidds' first wedding anniversary.

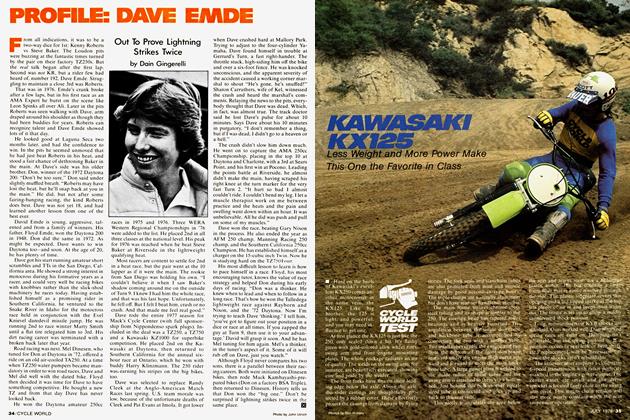

Motorcycle cycle racers racers get crash. hurt. This Motoris terrible, but nothing can be done about it. Yet why, those in the sport raged last year at the time of Mike Kidd's crash, did it have to be Kidd? Mike Kidd, you see, is one racer you automatically root for whether you know him well or not. He happens to be almost everyone's candidate for the "nice guy" award. That sounds trite, but there's no other way of putting it. Licensed professionals in Grand National motorcycle racing who claw their way to the top are, as a group, aggressive people indeed. Some of them make car racing's fiery A.J. Foyt seem as tame as a choir boy by comparison. But Mike Kidd, National No. 72, isn't that way at all. Fle's guileless, mild, and, well. . . nice. His vocabulary is spotless, you won't hear him using profanity, and he's the straightest arrow of all the racers. He refrains from smoke and drink not because he believes such things are wrong, but because he honestly doesn't see the need. "I can't remember the last time I took a drink of beer," he says, "or have been drunk. And I've never smoked a marijuana cigarette. I think I'm proud of that."

Mike Kidd is, in fact, the type of individual about whom Bill Boyce, director of competition for the American Motorcycle Association, might like to say, "I wish we had a hundred more like him."

Kidd's niceness is in no way faked. He just doesn't have it in him to be harsh with anyone. Most riders in his place might have been outraged that no protective haybales had been stacked in front of the Santa Fe crashwalis. The AMA rule book states that haybales are mandatory. But, although Kidd agreed that the haybales might have prevented his serious leg injury, he refused to attack the Santa Fe management. "Maybe the promoter just couldn't afford the haybales," he offered. "I don't know, but in the future I'm sure us riders would be willing to pitch in a dollar or two to buy haybales at a track if a promoter can't afford them."

Many riders, too, might have had blistering words for a motorcycle that sent them careening into a hard wall at 70 mph. Not Mike Kidd. He blamed himself for the spill. "The Bultaco I was riding was jumping out of gear, and had been jumping out of gear in the heat race earlier," he said, "but the crash was my fault. I should have changed engines between the heat race and the main event. I feel like if I'd of changed engines, there wouldn't have been no accident, and I wouldn't have been knocked out of racing for the rest of 1974."

Kidd also seems the antithesis of the money-hungry professional who races motorcycles out of greed, not love of the game. "For sure," Kidd said, "you can make good money racing motorcycles if you do it right. But I'm not really racing for the money, I don't guess. I want to make a living at this, but I love the racing, too. Shucks, it's hard to explain. . . ." He paused.

"I guess what I really feel," he finally continued, "is that for somebody who's only 21 years old, I'm doing okay. I'm making pretty good money. Sure, I could go to college for a couple of years, come out, and probably earn the same amount doing something safer than racing. But as soon as the thought crossed my mind, I'm sure I'd say to myself: 'No way. I can't quit.'

"I can look at what I'm doing, and what the kids I went to high school with are doing, and there's no comparison. I'm definitely better off racing. Some of them are digging ditches. And you know for sure that they don't like doing it, that it's not what they really want to do with their lives."

Mike said: "My dad started me racing quarter-midget cars when I was five in Dallas. He's a race promoter at Ross Downs Short Track. By the time I was eight, I'd won two quarter-midget championships. When I was 12, I started racing motorcycles. I raced amateur TT steeplechases until I was 14. Later, I did me some motocross. Motocrossin' broke me up a lot. When I finally started racing bikes on short tracks, I found what I liked best. Then I found myself on big motorcycles racing half-miles and miles. I liked them a whole lot better."

Someone overhearing Mike Kidd's comments, and not knowing who he is, might be lulled into thinking that somehow this well-mannered and—here's that word again— nice boy would be a complete pushover in a race, unwilling to make a fight of it. People used to believe that about Kidd. But the truth is that Mike has a will of steel about winning—or is it a desire to please?—that can be frightening at times. In addition to that, he can really do tricks when in full cry aboard a big flat track motorcycle.

Columbus, Ohio, last year, in the Grand National dirt track race, was where Kidd, racing a factory Triumph, proved he was for real.

"At Columbus,” he says, "I felt good because during my heat race I could run right with Mert Lawwill's Harley. The whole day Sandra was a-tellin' me that this was going to be my day, this was going to be my first Grand National win.

"But not until in the National when I broke away from Mert and was running 2nd to Kenny Roberts did I get all excited. I saw I was closing on Kenny. I would say I was picking up two bike lengths a lap on him—quite a bit on a half-mile. And it dawned on me—gosh, I could win this thing! 'C'mon, Man,' I thought, 'let's do some business.'

"I was getting a much better drive off turn four than Kenny was and figured that was where I'd pass him if I could. On the third to last lap I pulled up beside Kenny. I showed him my front wheel. He knew I was there. Coming for the white flag I went outside of him in turn four. I knew if I didn't pass him then, that he'd move up there himself.

"For that whole last lap I almost died. I was leading Kenny Roberts. And I knew if I didn't blow it by riding the high cushion, that I'd win it."

Kidd not only won Columbus, he established a brand new track record that went unbroken this year.

(Continued on page 52)

Continued from page 46

"Mike Kidd," said Roberts afterwards, "is a really good cushion-track rider, one of the very best in the country."

Two-thousand miles from Columbus, in California, a couple of weeks later, Kidd kept up his good work at the San Jose Mile. He left behind the factory Yamahas of Roberts and Gene Romero and fought Harley-Davidson star Gary Scott to a draw after Scott tried to bluff him into slowing down early for a tricky corner.

"I knew," Kidd said later, "that if I shut off for him that one time, then Gary would do that to me for the whole race. And, at the next race track, maybe he'd try it all over again. So, there was just no way I could let him do that. No way at all." Kidd still finished 2nd to Scott in the race.

These were two terrific rides turned in by Kidd. And they occurred while Mike was aboard the only factorybacked Triumph in Championship dirt track racing. Each racing season only a handful of fully-sponsored factory rides are available, and competition to land one is keen. Mike Kidd landed his despite the fact that he didn't live in Southern California (where the U.S. distributors for Yamaha, Suzuki, Kawasaki, Norton-Triumph and Honda all are located), and never kissed-up to anyone, did not politic at all in fact. He landed the ride, Kidd likes to believe, because he was a good racer and he deserved it, and because Norton-Triumph realized that you didn't have to be from Southern California to be a good motorcycle racer.

"But, for awhile, in 1972, I was about ready to leave Texas and move to Southern California just to get noticed," Kidd admitted. "Los Angeles has that Ascot track, and that seems to be where all the factories go to pick out their new riders. Ascot guys get all the publicity. Down home in Dallas we might have guys going just as fast, but you don't seem to read about them." Kidd went to Ascot and became one of only five out-of-state riders to ever win a main event there. The others were Bart Markel, Gary Nixon, Corky Keener and Rex Beauchamp. Maybe that did him some good.

"The real reason Norton-Triumph signed me in late 1973," Kidd says, "was that Gary Scott had decided to go with Harley and to leave Triumph. If Gary'd stayed with them, I don't think they'd of signed me like they did."

Whatever the reason, Kidd will never forget how emotional he became while signing the contract that made him a full-fledged factory rider. There were tears in his eyes, almost.

"Boy, when I signed that piece of paper, I appreciated it more than anything anybody ever did for me. I'm not a businessman. When I go talk about a contract I don't really know what I'm talking about. This was something I'd worked for, put in a lot of years racing for, but I shore appreciated it. NortonTriumph didn't have to hire me, or pay me a salary. There's hundreds of racers. But they wanted me, Mike Kidd. And, they were giving me a lot."

It worked both ways. NortonTriumph was buying a lot of motorcycle racer with that $12,000-a-year contract. Kidd was a find. His talent was obvious. So was his dedication. He was also married and settled. "When you're not married," he said, "you're more likely to go out and get drunk and mess around and not be one-hundred percent concentrating on your racing. But I think I'm settled down as much as a racer can be."

There was another thing too. Mike Kidd was nice, a very nice boy.

Ah, but you know what they say about nice guys. They finish last. Kidd's 1974 Santa Fe Speedway crash seemed to bear this out, but there was more to come.

Kidd that spent loathsome a couple Chicago more weeks hospital, in then was flown back to Texas and his still-new home, and got a new doctor (who immediately placed him in a bulky body cast). He became, somewhat unwillingly, a sucker for soap operas. He passed 10 weeks in the body cast, three more in a wheel chair, then spent a month using crutches and finally a cane. In December he felt well enough to drive to Southern California to visit the Norton-Triumph works and sign his 1975 contract. We had lunch together. Kidd's weight during his convalescence had fallen from 133 to 110 pounds. Gimping about on his cane, I thought he still looked shriveled and underfed. During lunch I attempted to bait Mike and draw him out. He'd been through a lot. That ambulance ride from the Santa Fe Speedway to the hospital had been a nightmare in itself. So why race motorcycles again?

Kidd wouldn't bite. Quitting racing had never occurred to him.

"Getting hurt, that's something a racer has to cope with," he said, smiling. "Every time you get hurt you try to find an excuse for it. You don't want to admit that maybe you just dropped the bike and made a mistake. If you say that, well, you know you'll just get back up and fall down again. I wish you could race without breaking things, but. . . ." He shrugged, still smiling.

He said: "I'll tell you who this has been hard on, and that's Sandra. But never one time did that girl ask me to quit. People'd talk to her about it and she'd say, "Mike can't quit racing. That's how he makes his living.' "

Kidd was looking forward to 1975's January opening race inside the Houston Astrodome. "I've had people say, 'Well, you broke your leg. That'll slow you down.' But they're wrong. I've broken many a bone racing before getting hurt at Santa Fe, and none of them slowed me down any. Of course, at Houston there's no way I'm going to be 100 percent ready. I can say that I'm going to be. . .but, realistically, there's no way. My leg may be ready, but, physically, the rest of my body can't be ready. Maybe for the first 10 laps I'll be able to go hard, but then I'll start getting tired out. I'm going to try, though. I'm going back to Texas and begin a conditioning program you wouldn't believe.

"My sponsors here are counting on me," he added.

We said goodbye, and Kidd returned to Texas and worked out constantly. Riding, running and eating, he gained back 13 pounds in a few weeks. A week before the Astrodome he rebroke the same leg. He stuffed his foot into a hole while riding at his father's track, and the bone broke again. Later he was in formed that the leg had never really healed satisfactorily, that a calcium de posit on the bone had been giving a false reading during X-rays.

(Continued on page 91)

Continued from page 52

The worst part was yet to come. While Kidd was being patched up in a Dallas hospital, a man from Norton Triumph visited him. Sorry, Mike, the man said in effect, we can't wait for you to heal, and we are paying you off and dropping you from our race team. We're giving your team bikes to John Hateley.

Was that cold, or what?

No official announcement of this was ever made, however. And Kidd himself, on the telephone, never mentioned it to me. Maybe his feelings were too badly hurt. In any case, bad-mouthing his former sponsors obviously was not in him. I decided that his enthusiasm was gone.

"I'm trying to tell myself that break ing my leg for the second time was for the best," he said, "and that now my leg will heal real proper. But I don't know what I'm going to do. I don't know how I'm going to keep up my house payments."

He returned home in a body cast again, and Sandra took care of him, and again he found himself passing the endless hours staring into the TV and worrying about Erica Kane Martin. Her name was now Erica Kane Brent-she'd remarried during one of the episodes Kidd had missed.

In April, a spokesman for Norton Triumph finally confirmed the firing of Mike Kidd. It sounded like the end of the line for the little Texan.

"We wish we could have kept Mike," said the spokesman. "He's a great racer. Maybe someday we'll have him back. But right now we have the bikes, and we have to race them. We can't leave them sitting. Mike's been hurt a lot-he's a little guy and it's possible that his bones are just too brittle for him to race motorcycles any more. It's too bad, but that's the way it is."

N o, that's not the way it is, this is the way it is. Kidd remained a prisoner in his own house-waiting for his bones to heal a second time— until June. He'd had plenty of time to plan what he was going to do with the rest of his life, including a possible career in midget race cars— an absurd scheme that he wisely discarded. Then a Texas neighbor and friend, Vernon Kruger, offered him an XR model Harley-Davidson to race. Kidd made his comeback ride in the annual hill climb up Pikes Peak in the Colorado Rockies. He won. He looked healthy and strong again. Then he won a Saturday night short track race at Sturgis, South Dakota, in August, and followed it up with a win the following day in a Pacific Regional half-mile. After that he went back to Santa Fe Speedway and, on the track that had nearly crippled him the year before, Mike Kidd qualified for and earned a place in the Grand National race.

(Continued on page 92)

Continued from page 91

Two days later, on a muggy Hoosier afternoon at Terre Haute, Kidd lined up on the front row for the 20-lap Camel Pro Series race. Arrayed against him were the likes of Gary Scott and Mert Lawwill, and the factory bikes from Yamaha and Harley-Davidson. Conspicuously absent was the NortonTriumph outfit; the entire racing team had been disbanded a month earlier after suffering a disastrous season without Kidd.

Kidd made a perfect start and shot straight into the lead. He fought Rex Beauchamp for a while. Then, with one lap to go, Kidd was leading. The emotion was building inside him, too. Tears of joy were actually forming in Mike's eyes. Finally he flicked Vernon Kruger's Harley sideways in the final corner, then put it straight up and down on the last straightaway, fed in the throttle, and took the checkered flag going full tilt.

Other people besides Mike were shedding real tears by then, including Sandra Kidd and Mike's entire pit crew. That nice boy Mike Kidd had starred in a soap opera of his own making this tumultuous afternoon. He'd won, he'd won! "Oh, my, it's nice," he said afterwards. And it really was. "The leg felt fine," Mike added. "It's as strong as ever."

Forget what they say about nice guys and where they finish.

There's one other thing, too.

From now on, someone else's going to have to worry about Erica what's-hername. Mike Kidd will be too busy racing. gj

View Full Issue

View Full Issue