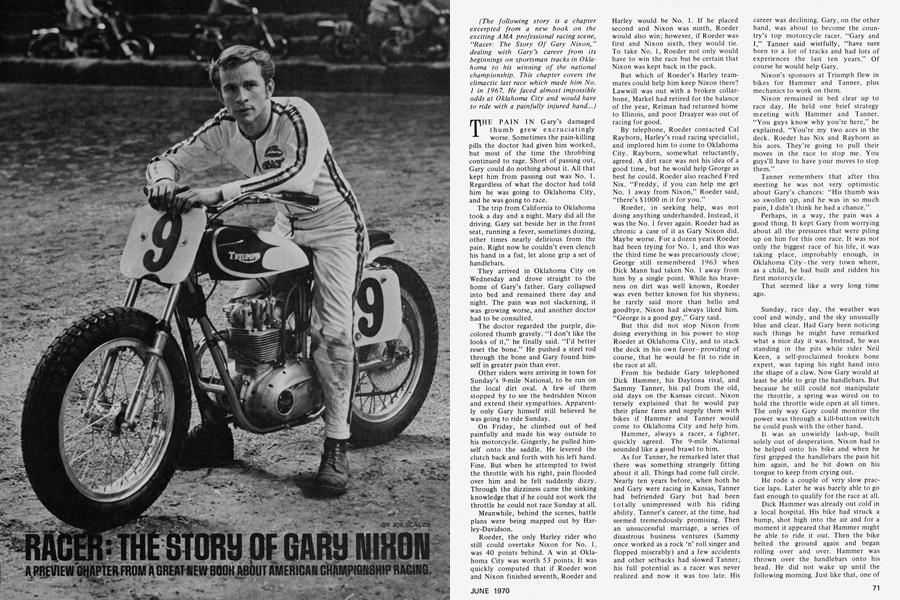

RACER: THE STORY OF GARY NIXON

A PREVIEW OHAPTER FROM A GREAT NEW BOOK ABOUT AMERICAN CHAMPIONSHIP RACING.

JOE SCALZO

(The following story is a chapter excerpted from a new book on the exciting AMA professional racing scene, "Racer: The Story Of Gary Nixon," dealing with Gary's career from its beginnings on sportsman tracks in Oklahoma to his winning of the national championship. This chapter covers the climactic last race which made him No. 1 in 1967. He faced almost impossible odds at Oklahoma City and would have to ride with a painfully injured hand...)

THE PAIN IN Gary's damaged thumb grew excruciatingly worse. Sometimes the pain-killing pills the doctor had given him worked, but most of the time the throbbing continued to rage. Short of passing out, Gary could do nothing about it. All that kept him from passing out was No. 1. Regardless of what the doctor had told him he was going to Oklahoma City, and he was going to race.

The trip from Californ-ia to Oklahoma took a day and a night. Mary did all the driving. Gary sat beside her in the front seat, running a fever, sometimes dozing, other times nearly delirious from the pain. Right now he couldn’t even clench his hand in a fist, let alone grip a set of handlebars.

They arrived in Oklahoma City on Wednesday and drove straight to the home of Gary’s father. Gary collapsed into bed and remained there day and night. The pain was not slackening, it was growing worse, and another doctor had to be consulted.

The doctor regarded the purple, discolored thumb gravely. “I don’t like the looks of it,” he finally said. “I’d better reset the bone.” He pushed a steel rod through the bone and Gary found himself in greater pain than ever.

Other riders were arriving in town for Sunday’s 9-mile National, to be run on the local dirt oval. A few of them stopped by to see the bedridden Nixon and extend their sympathies. Apparently only Gary himself still believed he was going to ride Sunday.

On Friday, he climbed out of bed painfully and made his way outside to his motorcycle. Gingerly, he pulled himself onto the saddle. He levered the clutch back and forth with his left hand. Fine. But when he attempted to twist the throttle with his right, pain flooded over him and he felt suddenly dizzy. Through the dizziness came the sinking knowledge that if he could not work the throttle he could not race Sunday at all.

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, battle plans were being mapped out by Harley-Davidson.

Roeder, the only Harley rider who still could overtake Nixon for No. 1, was 40 points behind. A win at Oklahoma City was worth 53 points. It was quickly computed that if Roeder won and Nixon finished seventh, Roeder and Harley would be No. 1. If he placed second and Nixon was ninth, Roeder would also win; however, if Roeder was first and Nixon sixth, they would tie. To take No. 1, Roeder not only would have to win the race but be certain that Nixon was kept back in the pack.

But which of Roeder’s Harley teammates could help him keep Nixon there? Lawwill was out with a broken collarbone, Markel had retired for the balance of the year, Reiman had returned home to Illinois, and poor Draayer was out of racing for good.

By telephone, Roeder contacted Cal Rayborn, Harley’s road racing specialist, and implored him to come to Oklahoma City. Rayborn, somewhat reluctantly, agreed. A dirt race was not his idea of a good time, but he would help George as best he could. Roeder also reached Fred Nix. “Freddy, if you can help me get No. 1 away from Nixon,” Roeder said, “there’s $1000 in it for you.”

Roeder, in seeking help, was not doing anything underhanded. Instead, it was the No. 1 fever again. Roeder had as chronic a case of it as Gary Nixon did. Maybe worse. For a dozen years Roeder had been trying for No. 1, and this was the third time he was precariously close; George still remembered 1963 when Dick Mann had taken No. 1 away from him by a single point. While his braveness on dirt was well known, Roeder was even better known for his shyness; he rarely said more than hello and goodbye. Nixon had always liked him. “George is a good guy,” Gary said.

But this did not stop Nixon from doing everything in his power to stop Roeder at Oklahoma City, and to stack the deck in his own favor—providing of course, that he would be fit to ride in the race at all.

From his bedside Gary telephoned Dick Hammer, his Daytona rival, and Sammy Tanner, his pal from the old, old days on the Kansas circuit. Nixon tersely explained that he would pay their plane fares and supply them with bikes if Hammer and Tanner would come to Oklahoma City and help him.

Hammer, always a racer, a fighter, quickly agreed. The 9-mile National sounded like a good brawl to him.

As for Tanner, he remarked later that there was something strangely fitting about it all. Things had come full circle. Nearly ten years before, when both he and Gary were racing in Kansas, Tanner had befriended Gary but had been totally unimpressed with his riding ability. Tanner’s career, at the time, had seemed tremendously promising. Then an unsuccessful marriage, a series of disastrous business ventures (Sammy once worked as a rock ‘n’ roll singer and flopped miserably) and a few accidents and other setbacks had slowed Tanner; his full potential as a racer was never realized and now it was too late. His career was declining. Gary, on the other hand, was about to become the country’s top motorcycle racer. “Gary and I,” Tanner said wistfully, “have sure been to a lot of tracks and had lots of experiences the last ten years.” Of course he would help Gary.

Nixon’s sponsors at Triumph flew in bikes for Hammer and Tanner, plus mechanics to work on them.

Nixon remained in bed clear up to race day. He held one brief strategy meeting with Hammer and Tanner. “You guys know why you’re here,” he explained. “You’re my two aces in the deck. Roeder has Nix and Rayborn as his aces. They’re going to pull their moves in the race to stop me. You guys’ll have to have your moves to stop them.”

Tanner remembers that after this meeting he was not very optimistic about Gary’s chances: “His thumb was so swollen up, and he was in so much pain, I didn’t think he had a chance.”

Perhaps, in a way, the pain was a good thing. It kept Gary from worrying about all the pressures that were piling up on him for this one race. It was not only the biggest race of his life, it was taking place, improbably enough, in Oklahoma City-the very town where, as a child, he had built and ridden his first motorcycle.

That seemed like a very long time ago.

Sunday, race day, the weather was cool and windy, and the sky unusually blue and clear. Had Gary been noticing such things he might have remarked what a nice day it was. Instead, he was standing in the pits while rider Neil Keen, a self-proclaimed broken bone expert, was taping his right hand into the shape of a claw. Now Gary would at least be able to grip the handlebars. But because he still could not manipulate the throttle, a spring was wired on to hold the throttle wide open at all times. The only way Gary could monitor the power was through a kill-button switch he could push with the other hand.

It was an unwieldy lash-up, built solely out of desperation. Nixon had to be helped onto his bike and when he first gripped the handlebars the pain hit him again, and he bit down on his tongue to keep from crying out.

He rode a couple of very slow practice laps. Later he was barely able to go fast enough to qualify for the race at all.

Dick Hammer was already out cold'in a local hospital. His bike had struck a bump, shot high into the air and for a moment it appeared that Hammer might be able to ride it out. Then the bike belted the ground again and began rolling over and over. Hammer was thrown over the handlebars onto his head. He did not wake up until the following morning. Just like that, one of Nixon’s aces was yanked from the deck.

His other ace, Tanner, was not going particularly fast and seemed to be having difficulty adjusting to the strange track and strange bike.

But things were not going too well for Harley, or for Roeder, either. Fred Nix had crashed during practice and wiped out his good bike; the back-up machine he switched to wasn’t as fast. And Rayborn, still a road racer at heart, was just coasting around while trying to adjust to the rutted dirt corners.

Only George Roeder himself was going well. He looked unbeatable while riding his bike to a new track record during the qualification runs.

In the pits Gary, nervous, kept chewing aspirins to blunt the pain of his swollen thumb; at the same time he had to be careful he didn’t chew too many because they might blunt his reflexes as well. Mary Nixon watched him intently from the grandstands and wished she could do something, anything. She was on the verge of tears all afternoon.

The qualifying heat races were duly run off. Nix won the first one, beating teammate Roeder by a few feet. Dick Mann won the seond one—and Nixon, struggling forward from the back row, was able to finish second.

At least, Gary sighed, I’ve won a starting place in the National.

The makeshift throttle arrangement on his Triumph was examined a final time; he held a last-minute consulation with Tanner, his ace; then his bike and all the others were pushed to the line. Gary had to be helped into his helmet, and helped onto his bike. He studiously avoided looking at Roeder, or chatting with him:

It was Fred Nix who powered his Harley off the front row and into the lead at the start. Tanner was second, Nixon was third. Gary had already accomplished part of his objective—he had beaten Roeder off the line. But Roeder was sitting directly behind him.

This was a race where Nixon did not have to ride fast, just be steady. He could in fact had “backed” in to No. 1 by permitting Roeder to pass him, then merely tailgating him for the rest of the distance. As long as Roeder did not get too many riders between them, Gary would automatically win No. 1.

But Gary, as if wanting to prove that he was fast as well as lucky, proceeded to run away from Roeder!

How, no one knew. Nixon’s thumb was throbbing with pain. Worse, the makeshift throttle arrangement on his Triumph made controlling the heavy, brakeless bike difficult, if not impossible. Gary would dive into a corner under full power, his only method of slowing down being to jab the kill-button. When he hit the button with his left hand, his engine would die and his speed would drop enough for him to make it safely around the corner. Then he would let up on the kill button, the engine would scream, his rear tire would bite into the track, and he would quickly be back to peak speed again.

In spite of these handicaps he pulled away from Roeder.

And soon he was also closing in on Nix and Tanner ahead of him.

Tanner had been doing his job admirably. Gary’s orders to him had been to ride Fred Nix’s rear wheel for the whole race, and not let Roeder by him at any cost.

Therefore when Tanner heard a growling engine immediately behind him he expected it to be Roeder, and prepared himself for a rugged battle.

Instead it was Nixon himself. Tanner promptly pulled over and let Gary go past into second place. And as he rushed by, Gary happily flashed Tanner the “thumb’s up” victory sign-broken thumb and all.

That was the way the Oklahoma City race finished, with Nix the winner, Nixon second, Tanner third, and a dispirited Roeder a beaten fourth, his dreams of No. 1 crushed forever.

No one had been prepared for such an outcome; it was just too improbable. Tanner rushed up to Gary and recklessly threw both arms around him. “Think of it,” he exclaimed, “you hired all us guys to come down here to help you, and you didn’t need any of us. You did it all yourself—broken thumb and all. You’re No. 1!”

And up in the grandstands, fighting her way through the crush of spectators to get down in the pits to be with her husband, Mary Nixon was weeping unashamedly. “Oh, I’m just terribly emotional,” she wept. She had started to cry as soon as the race had started: “I knew about Gary’s broken thumb, and I knew there was tension between him and the other guys. And I was so worried that something more was going to go wrong.”

At the finish she was crying out of joy: “Oh, I’m just like a kid,” she screamed delightedly. “Gary’s done it; he’s really done it!”

The new No. 1 rider found himself in a state of shock. His thumb was throbbing wildly, but not as wildly as his heart. He felt tired, dazed, and what seemed like a million people were all trying to congratulate him at once. Some he thought he knew, others he wasn’t sure, but he loved all of them. Gary had a silly grin on his face, he was drenched in sweat, his ears were ringing and the taste of aspirin and dust in his mouth soon mingled with stronger stuff as the overjoyed Triumph mechanics broke open a case of beer to begin celebrating. It was not until the next morning, after all the noisy victory parties were done, that Gary fully realized what had occurred, what it all really meant, and how far he had come.

He was No. 1 at last.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

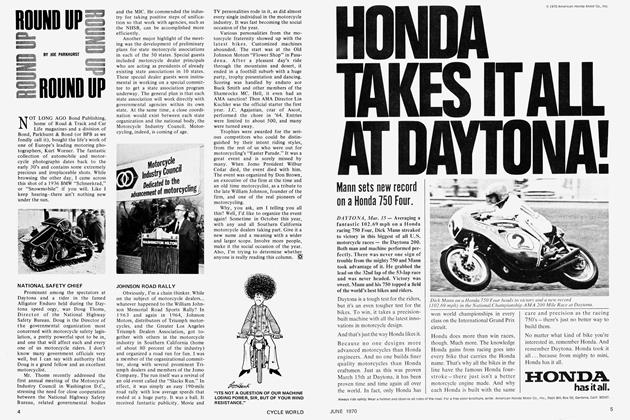

DepartmentsRound Up

JUNE 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Legislation Forum

Legislation ForumIllinois Success Story

JUNE 1970 By Lee Strobel -

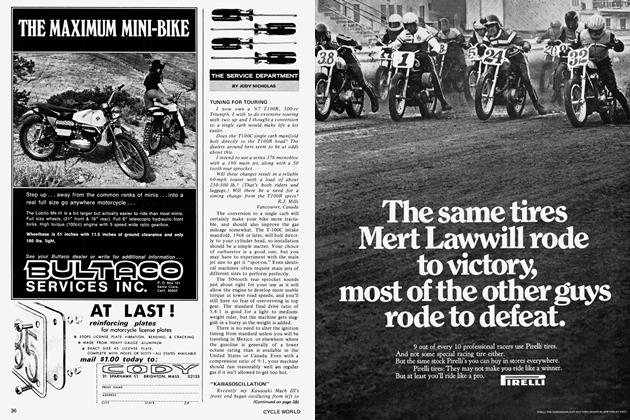

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

JUNE 1970 By Jody Nicholas -

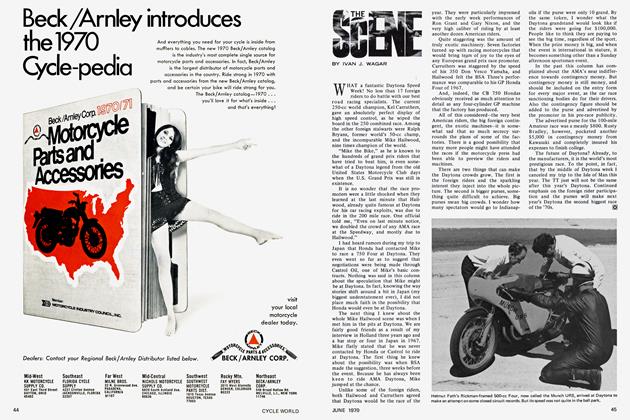

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

JUNE 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Special Competition Feature

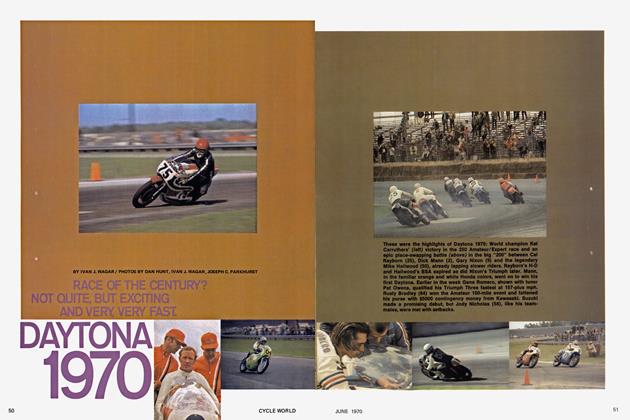

Special Competition FeatureDaytona 1970

JUNE 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Features

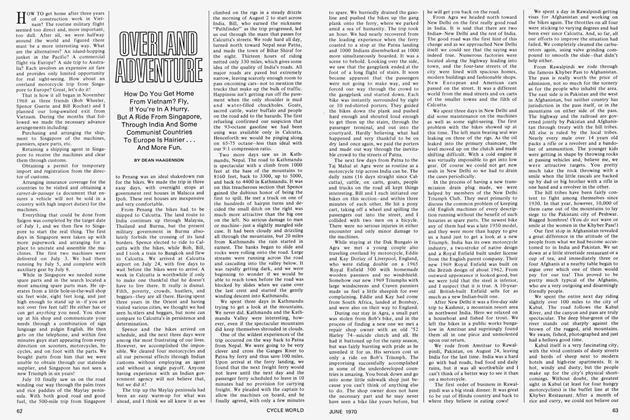

FeaturesOverland Adventure

JUNE 1970 By Dean Haagenson