ILLINOIS SUCCESS STORY

LEGISLATION FORUM

Fighting the Mandatory Helmet Law

LEE STROBEL

A GROUP OF SEVEN Illinois men, unversed in legislative procedures and without the help of any motorcycle manufacturer, distributor or magazine, brought about the repeal of the Illinois mandatory helmet law.

“There are a lot of laws which are inconvenient and discriminate against motorcyclists,” said Reed N. Ehrlich, 46, a Chicago businessman and organizer of the campaign. “Our success in Illinois just shows what can be accomplished when cyclists organize and use the democratic process to fight back.” Ehrlich is confident that the successful fight against the discriminatory helmet law in Illinois can be repeated in the many states where mandatory helmet laws, and other unfair legislation, remain in effect.

Ehrlich, who rides both Harley-Davidson XLCH and Sachs motorcycles, was a member of a group called the Committee on Legislation. Principle members included Chicago businessmen William Checkley, a commodity broker; Pete McDowell, auto parts salesman; Irwin Hirsh, jeweler; Reck Morgan, radio station owner and Ben Cozack, curator of the Chicago Field Museum; plus Kent Cadish, an electrician from Aurora, 111.

Members of the committee became acquainted through the Illinois State Motorcycle Association.

“I heard somewhere that the ISMA was organizing a fight to try to get the mandatory helmet law repealed,” said Ehrlich. “I mailed in my dues to join the group, hoping they would use my money to further the cause. A couple of weeks later I got a telephone call from someone asking that I work actively toward repealing the law. At first I said that I was too busy, but later I agreed to help.”

The group began with 15 members but, Ehrlich said, “there was a weeding out and it ended up with seven of us who really worked.”

At first, the Committee on Legislation was going to be under the direction of Illinois State Motorcycle Association President John Southwood. But because Southwood resides in Bridgeport, 111., a considerable distance from Chicago, he was unable to attend the committee’s frequent meetings. The group then began to work independently of the ISMA, advising Southwood of their progress.

The committee’s first task was to notify the 100,000 Illinois motorcycle owners that they intended to organize a fight against the helmet law. “We couldn’t afford to mail 100,000 letters,” Ehrlich said. “So we decided to contact these people through every kind of organization we could find.”

They notified a dealer’s group in northern Illinois called the Illinois Motorcycle Association and “they cooperated fully,” supplying names of dealers throughout the state. These dealers were instrumental in contacting motorcyclists who were not associated with a formal club.

The Committee on Legislation discovered, however, that the American Motorcycle Association would not allow them to use their mailing list of motorcycle clubs in Illinois. Their alternative was to write to every motorcycle club they could find and request that they send names of other clubs. They ended up with over 600 different groups and clubs on their mailing list. This cut their mailing costs and facilitated handling.

(Continued on page 32)

Continued from page 30

Ehrlich found that among the most cooperative and hard working groups he encountered were the many Illinois “outlaw” gangs. “Without their help,” Ehrlich said* “oiir campaign might not have been successful. They spent hours writing letters and working with us.”

The first campaign of the Committee on Legislation was to apply political pressure to Aurora State Senator Robert Mitchler. Mitchler introduced the original mandatory helmet law to the Illinois General Assembly. Kent Cadish, member of the Committee, organized'“about 98 percent” of the motorcycle riders in the Aurora area. They all wrote letters to Sen. Mitchler, saying that if he didn’t introduce a bill in the General Assembly to repeal the mandatory helmet law, they would do everything they could to discourage his re-election.

It was in July 1968, at a special meeting of the Illinois General Assembly, that Sen. Mitchler submitted a bill to repeal the helmet law to the Senate Highway Committee. Immediately the bill was voted down by the committee, 13-0.

According to Ehrlich, Sen. Mitchler never really expected the bill to pass. “He was just trying to pacify his constituents so that he would be re-elected,” Ehrlich said. “And, if he didn’t introduce that bill, I’m sure that he would have lost at the polls the next time around.”

Now the Committee on Legislation started another letter writing campaign. They told the 600 clubs on their mailing list to bombard members of the Senate Highway Committee with letters supporting repeal of the helmet law. It was later estimated that each senate committee member received in excess of 2,000 pieces of mail on the subject.

At the next session of the Senate Highway Committee, another vote was taken on the repeal bill. This time it passed, 11-3.

“The next step was to get the bill passed on the senate floor,” Ehrlich said. “Then we started another letter writing campaign. We applied pressure where it would do the most good—this time on the senators. You must aim your letters to the right people at the right time.”

Again, the Committee on Legislation asked its followers to write letters and, again, thousands were sent. Ehrlich traveled several times to Springfield, the Illinois state capital, to attend meetings and to speak with representatives, sena tors and with Governor Sam Shapiro.

(Continued on page 34)

Continued from page 32

i; many constituents were in favor of repealing the helmet law, they were eager to support it. There were 20 co-sponsors of the repeal bill in the senate and it was submitted by Sen. Robert Mitchier, the same man who introduced the original mandatory hel met law.

When the vote came up in the senate, the roll call showed only 11 out of 58 senators not in favor of repealing the law.

"The next step was to introduce the bill tO the House of Representatives," Ehrlich said. "Since Rep. Al Schober line, the state representative from Aurora, sponsored the original manda tory helmet law in the House, we persuaded him to sponsor the repeal of that bill. Then we sent letters out to let our group know to stop writing letters to senators and start writing them to representatives."

Again, thousands 0! letters poured into Springfield. The Committee on Legislation urged not only motorcycle owners to write letters, but also their families and friends. When the roll call was taken in the House of Representa tives, only 9 out of 158 state representa tives didn't support repeal.

"Illinois had never seen a campaign like we waged," said Ehrlich. "They had never received 75,000 or 100,000 letters on any matter in Springfield. Besides, we weren't asking for much. We weren't trying to move next door to anybody and we weren't trying to get free money. All we wanted was a simple thing-not to have to be told to wear those darn helmets all the time."

Ehrlich added, however, that his group was not against the wearing of motorcycle helmets, but was only against the fact that they were being told to wear them. "All of the members of the Committee on Legislation wear helmets," he said. "But we think that we should be able to decide for our selves things which affect only our selves. The wearing of helmets affects only the wearer."

At the same time the repeal bill was passing through the House of Represen tatives and was about to be declared law, a man in East St. Louis, Ill., took the mandatory helmet law to the Illinois Supreme Court. The law was ruled unconstitutional. "I expect that the Supreme Court went along because we raised such a fuss in Illinois that they were moved to go along with the will of the people," Ehrlich said. "Besides, by that time we had won our battle, anyway."

From the time the Committee on Legislation was organized and the man datory helmet law in Illinois was re nealed only seven months elaosed.

Now that word 01 the success 01 Ehrlich's committee in Iffinois is spread ing, he is receiving letters from all over the country from individuals seeking to initiate similar campaigns. Recently he met with representatives from Ohio who are attempting to have their mandatory helmet law repealed.

Among the advice that Ehrlich offers is not to mail form letters or petitions to state officials. He suggests that per sonal letters, telephone calls and person al visits be used. He also says not to be discouraged with the results of the first letters because they generally end up in the waste basket.

Most ot all, tflriicti saui tnat tne campaign has to be organized from the beginning "so that you don't spin your wheels." Political pressure, within the bounds of the democratic process, should be applied where it will do the most good.

Ehrlich hopes that someday all of the mandatory helmet laws in the United States will be repealed, adding: "We proved in Illinois it can be done!"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

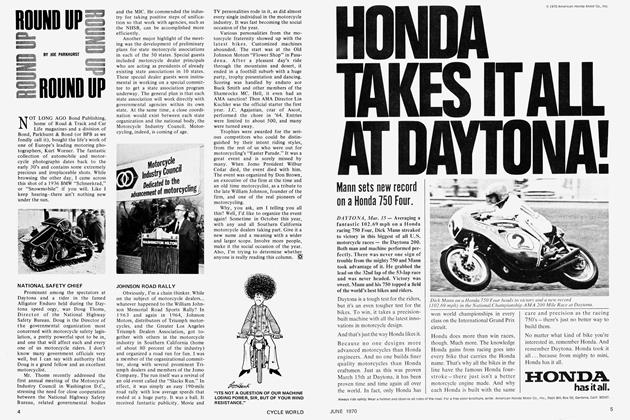

DepartmentsRound Up

JUNE 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

JUNE 1970 By Jody Nicholas -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

JUNE 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

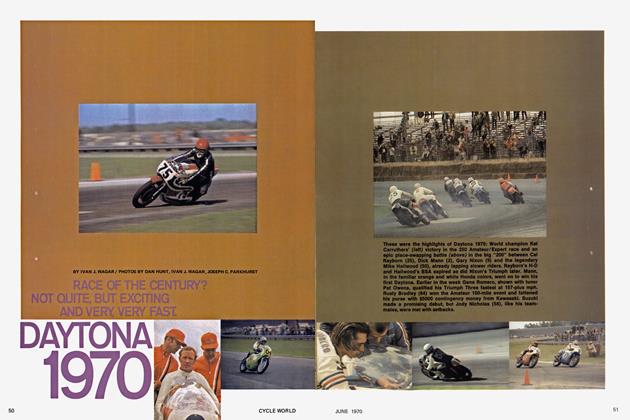

Special Competition Feature

Special Competition FeatureDaytona 1970

JUNE 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Features

FeaturesOverland Adventure

JUNE 1970 By Dean Haagenson -

Competition

CompetitionThe Mint 400, '70 Style

JUNE 1970 By Bryon Farnsworth